by Kaye Dee

I’ve written before about how much I love satellite spotting and this month has given me three new ‘man-made moons’ to watch out for, with the latest additions to NASA’s Explorer scientific satellite program. Each of the new Explorer satellites is very different and their research tasks are all of real interest to me, as I’m concentrating on space physics for my Masters degree. But before I talk about them, I’m excited to share the most recent news from Woomera.

A Textbook Test Flight

On October 20, the second test flight of the Blue Streak stage for ELDO’s Europa launch vehicle took place. After the problems that occurred towards the end of the first test flight, which led to the rocket’s flight falling short of its intended landing area (see June entry), this latest launch was a complete success, demonstrating that the fuel sloshing issue has been solved. The engines fired for the 149.1 seconds, fractionally over their anticipated performance, and the Blue Streak impacted almost 1,000 miles down range. Everyone at the WRE is really pleased (and relieved) with this textbook test flight, as it means that the Europa development program can now keep moving forward. Can’t wait for the next test flight!

Blue Streak F-2 prepares to blast off at Woomera’s Launch Area 6.

But what has really captured my attention this month are the new missions in NASA’s Explorer program (which I last covered on September 6 and October 16). This series of scientific satellites continues to study the near space environment around the Earth and the nature of the Sun, as well as contributing to astronomy and space physics.

Taking a Hit for Science

Explorer 23 was launched on 6 November, using a Scout rocket fired from NASA’s Wallops Island facility in Virginia, from which many satellites in the Explorer series have been launched. Also called S-55C, Explorer 23 is the third in a series of micrometeoroid research satellites. Explorer 13 (launched in August 1961) was the first in the series. It was also known as S-55A, following the failure of its predecessor, the original S-55 satellite (the S standing for Science). Explorer 16 (S-55B) was launched in December 1962. The purpose of the S-55 series is to gather data on the micrometeoroid environment in Earth orbit, so that an accurate estimate of the probability of spacecraft being struck and penetrated by micrometeoroids (very tiny pieces of rocks and dust from space) can be determined.

Explorer 13 was the first micrometeoroid research satellite to take a hit for science.

Each of the S-55 spacecraft is about 24 inches in diameter and 92 inches long, built around the burned out fourth stage of the Scout launch vehicle, which forms part of the orbiting satellite. Explorer 23 carries stainless steel pressurized-cell penetration detectors and impact detectors, to acquire data on the size, number, distribution, and momentum of dust particles in the near-earth environment. Its cadmium sulphide cell detectors were, unfortunately, damaged on lift-off and will not be providing any data. Explorer 23 is also designed to provide data on the effects of the space environment on the operation of capacitor penetration detectors and solar-cell power supplies.

(left) An illustration of Explorer 23 in orbit, showing its modified design compared to its predecessors. (right) Part of the backup Explorer 23 satellite.

Two Satellites for the Price of One Launch

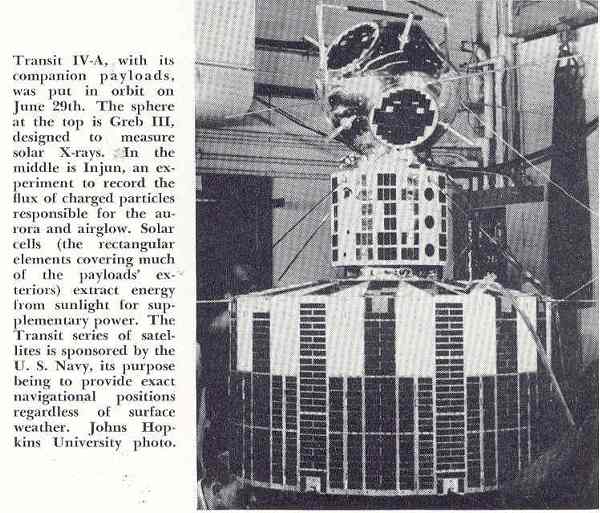

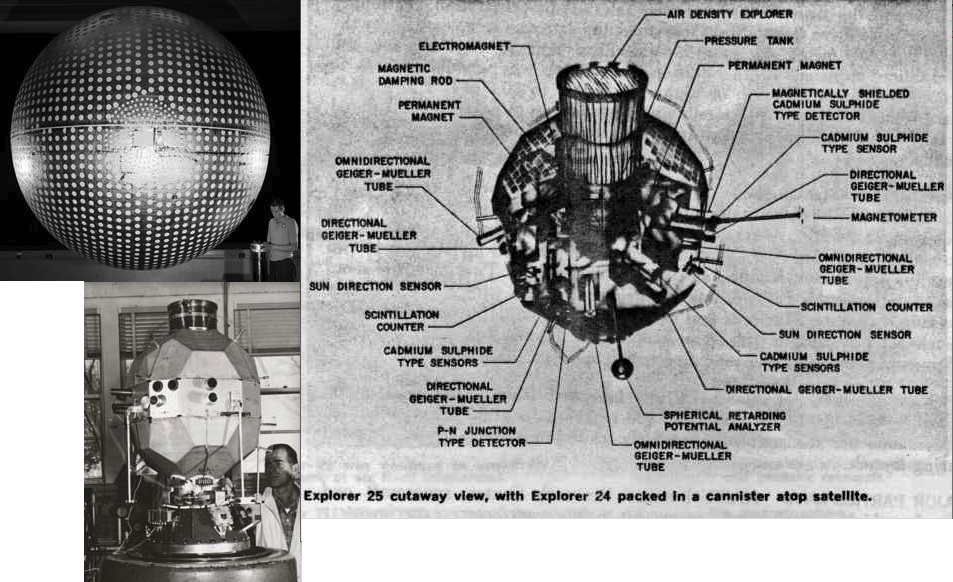

November 21 saw the Explorer 24 and 25 satellites launched together on a Scout vehicle fired from Vandenberg Air Force base in California, which will put the satellites in a near-polar orbit. These two Explorers have been launched as part of the research program for the International Quiet Sun Years (IQSY). Just as the International Geophysical Year took place in 1957-58, during a period when solar activity was at its height, the IQSY is focusing on the Sun in the least active phase of the solar cycle, across 1964-65. This makes it possible to compare the data from Explorer 24 and 25 with earlier observations made from orbit when the Sun was more active. Having the satellites in dual orbits also makes it possible to compare the atmospheric density data gathered by Explorer 24 directly with the radiation data from Explorer 25.

A stamp from East Germany highlighting satellite-based research into the Van Allen radiation belts and other aspects of the near-space environment during the International Quiet Sun Years.

Explorer 24: A Balloon in Orbit

Although the two satellites work in conjunction with one another, they couldn’t be more different! Explorer 24 is a 12-foot diameter balloon made of alternating layers of aluminium foil and plastic film. It’s covered all over with 2-inch white dots that provide thermal control. Deflated and packaged in a small container, the balloon was packed on top of the Explorer 25 satellite for their joint launch and then inflated in orbit. A timer activated valves that inflated the balloon using compressed nitrogen. This process took about 30 minutes, after which the satellite was pushed away from the carrier rocket by a spring.

Explorer 24 hitched a ride to orbit on top of Explorer 25, before being inflated in space.

Explorer 24 is identical to the previously launched balloon satellites Explorer 9 (launched in February 1961) and 19 (launched in December 1963). Explorer 19 was also known as AD-A (for Air Density) and Explorer 24 is also designated as AD-B. All three of the balloon satellites have been designed to provide data on atmospheric density near the perigee (lowest point) of their orbit, through a series of sequential observations as they move across the sky.

Like its predecessors, Explorer 24 will be tracked both visually and by radio, as it carries a 136-MHz tracking beacon. Explorer 19’s tracking beacon failed while it was in orbit, and so it could only be tracked visually by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory’s network of Baker-Nunn telescope cameras. There is one of these stations at Woomera and my former computing colleagues at the WRE’s Satellite Centre in Salisbury, South Australia, assisted with converting its observations into the orbital calculations that the scientific researchers needed.

Explorer 25: Studying the Ionosphere

Explorer 25’s primary mission is to investigate the Ionosphere, make measurements of the influx of energetic particles into the Earth’s atmosphere, studying atmospheric heating, as well as the Earth’s magnetic field. It will be magnetically stabilised in orbit through the use of a magnet and a magnetic damping rod and carries a magnetometer to measure its alignment with the Earth’s magnetic field. One of its particularly interesting tasks will be to study and compare the artificial radiation belt created by the Starfish Prime high-altitude nuclear explosion and the natural Van Allen radiation belts.

Explorer 25 is also known as Injun 4 and Ionosphere Explorer B (IE-B). It is the latest satellites in the Injun series, which have been developed at the University of Iowa under Professor James Van Allen, after whom the Van Allen radiation belts are named. Van Allen himself gave these satellites the name Injun after the character Injun Joe in Mark Twain’s Adventures of Tom Sawyer. The first three Injun satellites were only qualified success and were not actually part of the Explorer program. However, as IE-B, Injun 4/ Explorer 25 extends the research being carried by Explorer 20, that I wrote about in September.

James Van Allen (centre) with a replica of the Explorer 1 satellite, for which he provided the scientific instruments that contributed to the discovery of the Van Allen radiation belts. With him are William Pickering (left), the Director of the NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and (right) Wernher von Braun, whose team developed the Juno rocket that launched Explorer 1.

Explorer 25 is roughly spherical and almost 24 inches in diameter. It has 50 flat surfaces: 30 of them are carrying solar cells that are used to recharge the batteries that power the satellite. The satellite is also equipped with a tape recorder and analogue-to-digital converters, so that it can send digital data directly to a ground station at the University of Iowa.

Science Streaks Across the Sky

It is simply marvelous how rapidly we are expanding our knowledge of the universe above. Just seven years ago, there hadn't been a single Explorer; now there are twenty five! I’m looking forward to spotting all these science gatherers in the evening sky over the coming weeks — and eventually telling you what they find up there!

[Join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[November 23, 1964] Let’s Go Exploring! (NASA’s latest Explorer satellites)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/641123montage-672x372.jpg)