by Jason Sacks

Over the last five years or so, there has been a renaissance of movies which take science fiction concepts and turn them into fine — and often obscure — film art. For instance The brilliant Agnès Varda, perhaps best known for her amazing 1962 film Cléo from 5 to 7, used a kind of Island of Dr. Moreau motif for her film The Creatures (released in 1966). That film starts with a car accident and becomes a meditation on the way reality is changed by fiction.

Similarly, the equally brilliant Alain Resnais used the idea of limbo to emphasize the strange, surrealistic lives of the characters in his much-loved (and much-despised) philosophic meditation Last Year at Marienbad.

And anyone who saw Gennadi Kazansky and Vladimir Chebotaryov's charming 1962 film Amphibian Man couldn't prevent themselves from being caught up in the literal fish-out-of-water elements of that most magical and fascinating film.

The Face of the Creator

But the master of this mini movement (if there is such a movement) is Japanese director Hiroshi Teshigahara.

Teshigahara came to many American viewers and critics' attention with 1962's The Pitfall, a strikingly nonlinear semi-noir documentary fantasy (and yes it is all of that); the film shows the director's vast scope of vision and deep curiousity about the complexity of human nature.

Two years later he delivered The Woman in the Dunes, the film which truly won Teshigahara his international reputation. It won the Special Jury Prize at Cannes, and it was nominated for the Best Foreign Film Award by the Academy Awards folks. It's an astonishing work of film art, one of the finer films of the 1960s thus far. It also is haunting on several different levels.

Both Pitfall and Dunes are adapted by novels by the beloved avant-garde novelist Kobo Abe, winner of the Akutagawa Prize and Yomiuri Prize, among many other awards. Apparently Abe's writing style is often labyrinthine, vivid and sensuous in its original Japanese. That style has to be seductive for an ambitous director, and with his success with these two films, now Teshigahara has taken on another Abe film.

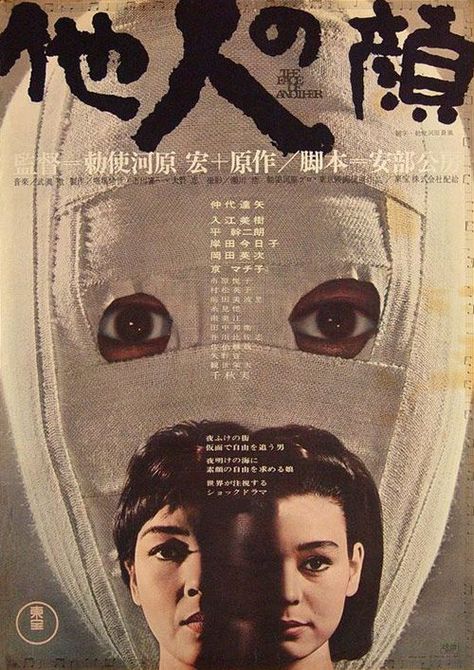

The Face of Another uses the idea of a facial transplant to explore the nature of identity, human connection, and the impact of the atomic bomb. At the same time it possesses a stunning visual style which will likely be studied for decades (and which will only be touched on briefly in this essay).

All of this makes for a heady mix, beautifully delivered on screen. The film is often obscure, looks beautiful and is well worth checking out in your local art cinema.

Let me tell you a little more about it.

The Face of Another

One thing I was struck by in watching this movie was in how much it echoes. There is a lot of Frankenstein in here – both Shelley and Karloff versions. It also echoes The Beast With Five Fingers and last year's Seconds, and definitely a lot of French New Wave cinema and even that episode of The Avengers in which the villains traded minds with Steed and Mrs. Peel. Face is original, sometimes radically original. Yet it stands on the shoulders of giants as well.

The movie follows two parallel plots. In the primary plot, a businessman named Okuyama has had his face damaged in a major industrial accident. Forced to live life with a full-face mask, he is horrified and even sadly bemused by peoples' reactions to him. No matter if it's his wife or a stranger, everyone is cold and unemotional to him. His lack of a face has imposed a deep outsider feeling on him. Okuyama is profoundly alone.

Our businessman is bereft, forgotten even by his own wife. Only a young girl with impaired intellectual abilities actually sees and reacts to Okuyma as his own self. Like the Invisible Man, he's an id in bandages, lost and empty. It's the impact of his injuries that matters rather than the injury itself.

In the second plot, a young (unnamed) woman has scars over half of her face. It's implied she got those burns during the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. Unlike Okuyama, the woman does not bandage herself, simply covering that side of her face with her hair and handling her pain with some grace.

Okuyama persuades his doctor to create a mask which will allow the bandaged man to look human and have some semblance of a normal life. He believes the mask will be seamless. It will allow him to pass himself off as normal person different than the man he was before.

He can become a new version of himself. And the first thing he does with his new freedom is… go to his old office and see if any of his former coworkers recognize him as their old compatriot (they don't). The second thing he does is even more banal. Frustrated beyond reason at his wife's indifference to him when bandaged, Okuyama decides to try to seduce his wife while wearing his new face. Yes, he's trying to make his wife an adulteress by sleeping with her.

Bizarre.

It's all as bizarre as the conversations Okuyama and the doctor have throughout different Osaka settings, including an odd German bar and the magnificent doctor's office.

Meanwhile, the girl is simply still wandering her life, unmoored and unrooted. Though she is spending much of her time with her brother who loves her (he may love her too much), she is alone. As with Okuyama, people recoil upon seeing her. Unlike with Okuyama, her injuries are more than just symbolic of a single man. Her injuries are a symbol of national guilt. And therefore she is simply more repulsive to the ordinary Japanese person.

I don't want to reveal the secret of how either of these powerful plotlines end — and in fact both endings are powerful.

Now that I've hopefully intrigued you with an idea of what makes the plot so great, let me talk about how great this film looks.

Looking at the Face

For all the praise Teshigahara deserves for his film, we all know a film can never be an individual effort (go ahead, Cahiers du Cinéma, prove me wrong!).

So let me first praise the cinematography of Hiroshi Segawa. His work here is simply extraordinary. The scenes at the doctor's office are symbolic and rich in meaning, not so much a setting as the implication of a setting and all the more powerful for that reason. The backgrounds symbolize all that Teshigahara is exploring in this meditative film.

Scenes on the streets or at bars are composed in beautiful framing and look sensational on screen. More importantly, they're composed in ways that allow Teshigahara to create doubling of his images (that is, the chance to use two images to echo each other).

As I've been alluding to, the production design by Masao Yamazaki is simply exquisite, a heady and head-bending approach to design that manages to both deeply root and profoundly confuse a viewer, a balancing act necessary for the film but incredibly hard to manage.

And of course I must praise our lead actors, especially Tatsuya Nakadai as Okayuma and Miki Irie as the man and woman, respectively. It's deeply impressive to see how richly Nakadai draws his character with his eyes while in his bandages, and with a deep, stiff complexity when wearing the mask. His body tells much of the story, and an attentive viewer can notice subtle physical changes which reflect his changing psychological state.

Irie's acting is equally as challenging and equally as rewarding. She's wearing a giant prosthetic and yet we feel we can easily read her emotions, hear her mood through slight voice inflections and body movements. He ultimate fate feels inevitable but not unexpected. That's a great compliment to Irie.

Looking at the Reasons Behind the Face

Teshigahara is clearly exploring many key themes here (isolation, collective guilt, and the intolerance of outsiders to name but three). I think the most intriguing explanation for this movie is to read it as a parable of the atomic bomb and the long recovery from the War.

Injury and disfigurement is common to see in Japan after the War. Even those who didn't directly experience the atomic bomb still felt the impact of the Bomb on their society. Nobody in Japan escaped those emotional scars. Our two lead characters just manifest those scars in their own particular way.

The Bomb also really and truly ended Japan's history as it had happened up to 1945. Its agrarian, peaceful traditions; its samurai code of ethics and its long and proud defiant isolation were all truly dead in their classical sense. Those were nation — and empire-affirming — concepts through the war. But those concepts were antiques, consumed by the never ending westernization of the post-war period.

Modernity was the future, tradition be damned. Ironically in a culture with a long, proud history of mask-wearing, Japanese people would be asked to put away their classic masks and don the western masks of hats and make-up worn in places like New York, London and Paris.

Furthermore, the Bomb and the subsequent westernization of Japanese society has served to isolate people by breaking down traditional societal structures and even the centrality of family. Akira Kurosawa has explored these topics as well, for instance in the sublime High and Low.

Teshigahara here takes a more symbolic approach than Kurosawa, forcing the viewer to contemplate the future that is developing. Teshigahara is unhappy about that future. The nihilistic ending of the film implies Japan is experiencing changes that might tear it apart.

Living with the Memory of the Face

Last year I raved about the John Frankenheimer film Seconds in these pages. As much as any of the other films I've discussed in this article, Seconds seems the best analogue for The Face of Another. It's a symbolic film, telling a despairing story about someone who gains a new face and goes just a bit crazy.

Both films feature brilliant black and white cinematography, fascinating lead performances, and linger long in the mind after they are done on the movie screen. I hope you didn't miss Seconds. And I hope you won't miss The Face of Another.

Four stars.

![[July 12, 1967] The masks we wear; the masks we must wear (the film: <i>The Face of Another</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/face-474x372.jpg)