by Erica Frank

Hair is a rapturous celebration of free love, higher consciousness, sexual adaptability, racial integration, and anti-authoritarianism. It's a critique of political corruption, the tragedies of war, and religious oppression. Also there is nature-based spirituality.

Hair is a debauched glorification of sex, drugs, perversion, profanity, and rebellion. It mocks public service, patriotism, and the church. Also there are fart jokes.

Pick one. Or take two; they're cheap. Everyone's got an opinion and none of them are the "real truth" about this complex and colorful stage production.

Note that the more positive description involves more words. It's easier to say something is bad–depraved, degenerate, vile, corrupt, and so on–than to praise something that doesn't fit into the established storytelling patterns of the day. And this musical–and its album–steps well off the common path to get its points across.

It's transcendental meditation versus the implacable forces of orthodoxy, and the prize at stake is the souls of a swarm of young people hanging out in Central Park.

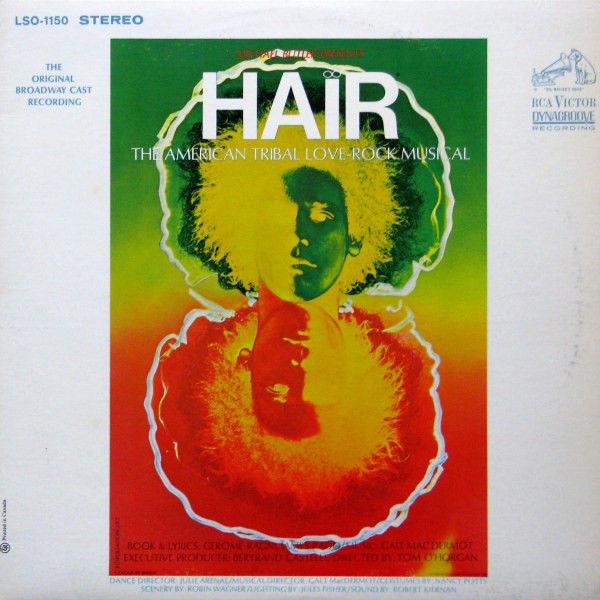

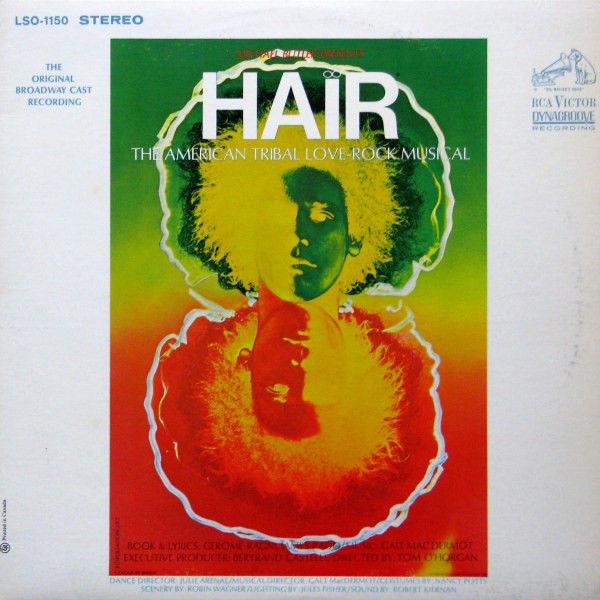

The cover is so striking you might not realize that the hair is not an artistic cloud-of-lightning addition–that's Steve Curry, who plays Woof in the Broadway cast.

Talk About Your Plenty, Talk About Your Ills

The music is incredible. From the opening "Aquarius" with its drumbeats and slow crooning that suddenly shifts to a cascading list of delightful assumptions of what the new era will bring, to the lascivious "Sodomy," to the jubilant "I Got Life," to the poignant "Easy to be Hard," the songs compel emotions with a shifting array of perspectives. The titular "Hair" is rebellious without hostility; "Don't Put It Down" is irreverent without contempt; "Three-Five-Zero-Zero" is stark and accusatory; "Good Morning Starshine" is bright and hopeful.

It's easy to get caught up in the music and miss the message–after all, the message is multi-directional and possibly contradictory. There's no one single theme I can point to and say, "this, this is the true message of Hair."

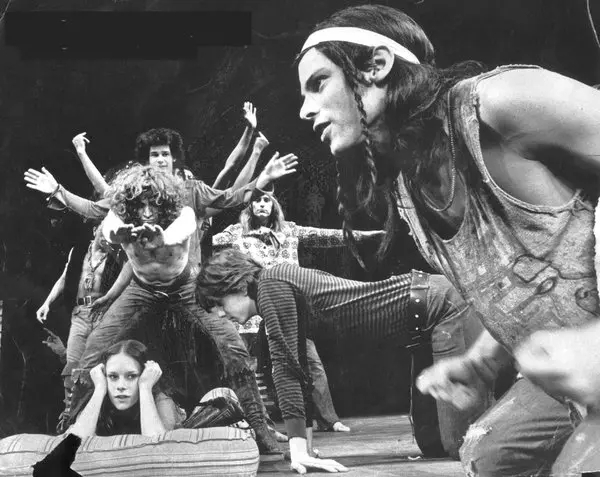

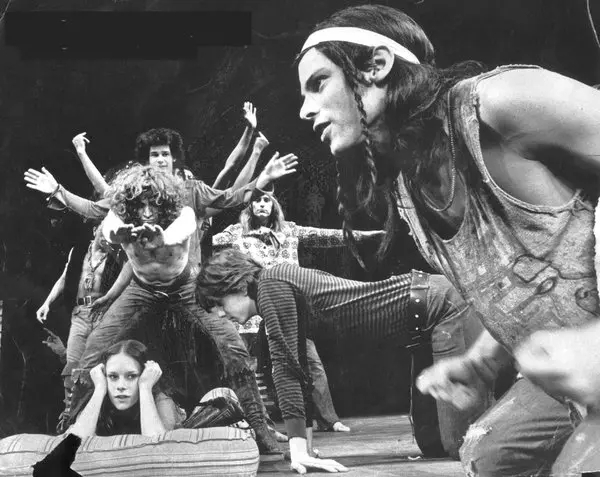

A scene from a performance last year, before the play hit Broadway.

It's anti-war, anti-draft. Those parts are simple enough. But it doesn't talk about war's influence on communities or even society–it talks about deaths of strangers happening far away, and young men who are afraid or (not unreasonably) unwilling to march off to fight and possibly die. This is not like Mark Twain's War Prayer; it's not a reminder that one side "winning" means another side enduring sorrows and agonies. This is instead, a view of war from the perspective of confused teenagers: A lack of comprehension why anyone would want to fight when the world seems on the verge of so many social and spiritual breakthroughs, when there is so much beauty and bliss and they could be partying instead.

War Is Not Healthy for Children and Other Living Things

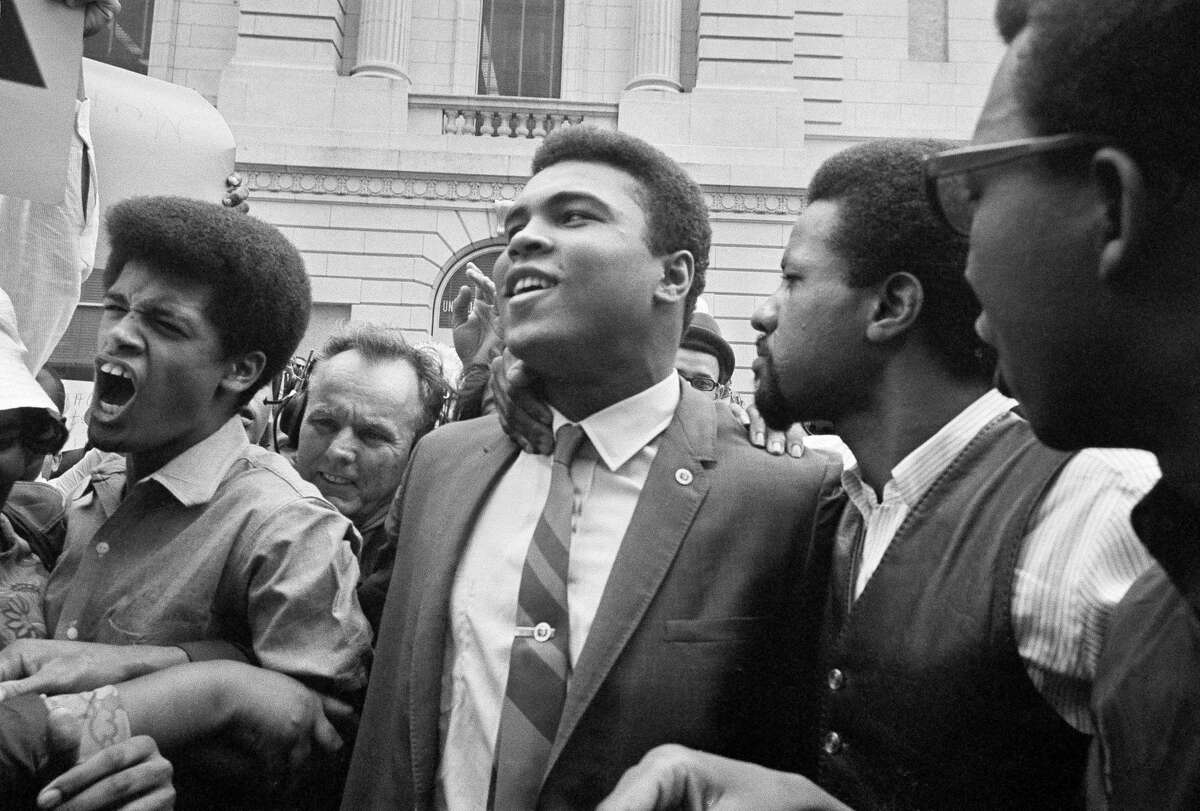

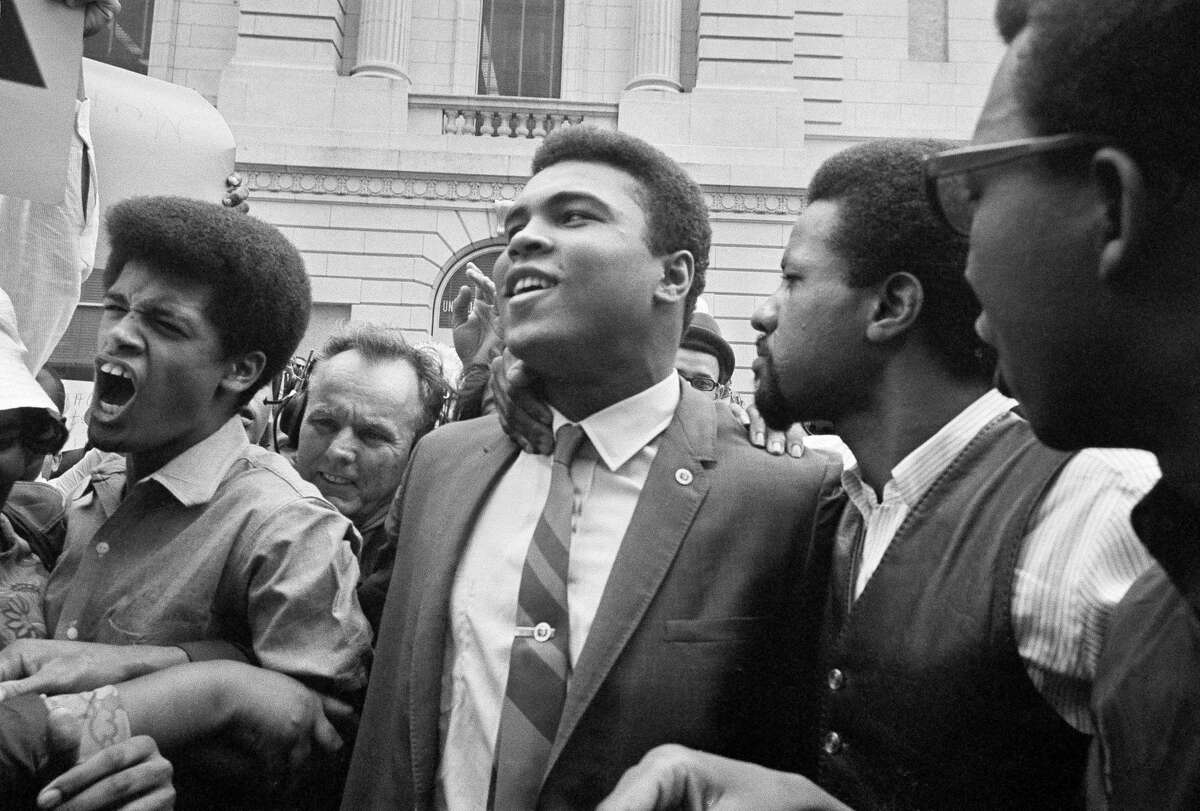

Sheila leads the tribe in chanting for peace and freedom. Claude denounces his parents for coupon-clipping and wanders the streets looking at daffodils. Hud quotes Muhammad Ali from the New York Times last year, saying, "The draft is white people sending black people to make war on yellow people to defend the land they stole from the red people."

Muhammad Ali and friends leaving the Armed Forces induction center in Houston after Ali refused the draft – April 28, 1967. | AP

There is something very true about that. And yet it is also facile, a simplification of a complex political situation. It boils the draft down to "why is this wrong for me" without consideration of why one nation might take up arms on behalf of another.

I do not think the US should be in Viet Nam at all, and we certainly shouldn't be drafting soldiers to send there. But my reasons for these beliefs are not discussed in Hair, which is focused on its "haggle of hippies" and their interests, which do not include political theory.

The play is obviously, overtly anti-racist. It denounces segregation and discrimination, speaks out against the white historical practice of "colonizing" by killing anyone who get in their way. But it does so by having black characters proudly claim the slurs thrown against them as badges of honor, by showing native peoples as "noble savages," insightful and wise but speaking with broken English. It does not show that some black people are uncomfortable with gutter slang, and would like to be lawyers, doctors, or professors, rather than street dancers and "President of the United States of Love." It does not show that some people hold all Americans, not just "the Establishment," in contempt. It celebrates white girls dating black boys and vice versa; there's no equal jubilation over black people who want nothing to do with the communities of their historical oppressors.

It's not inaccurate so much as it's incomplete, showing only narrow aspects of multi-faceted problems, a view so limited it could reasonably be called deliberately misleading. It preaches that peace, love, and tolerance can overcome all conflicts, settle all disagreements, glossing over any disputes that have their roots in limited resources or incompatible cultural differences.

The Politics of Ecstasy

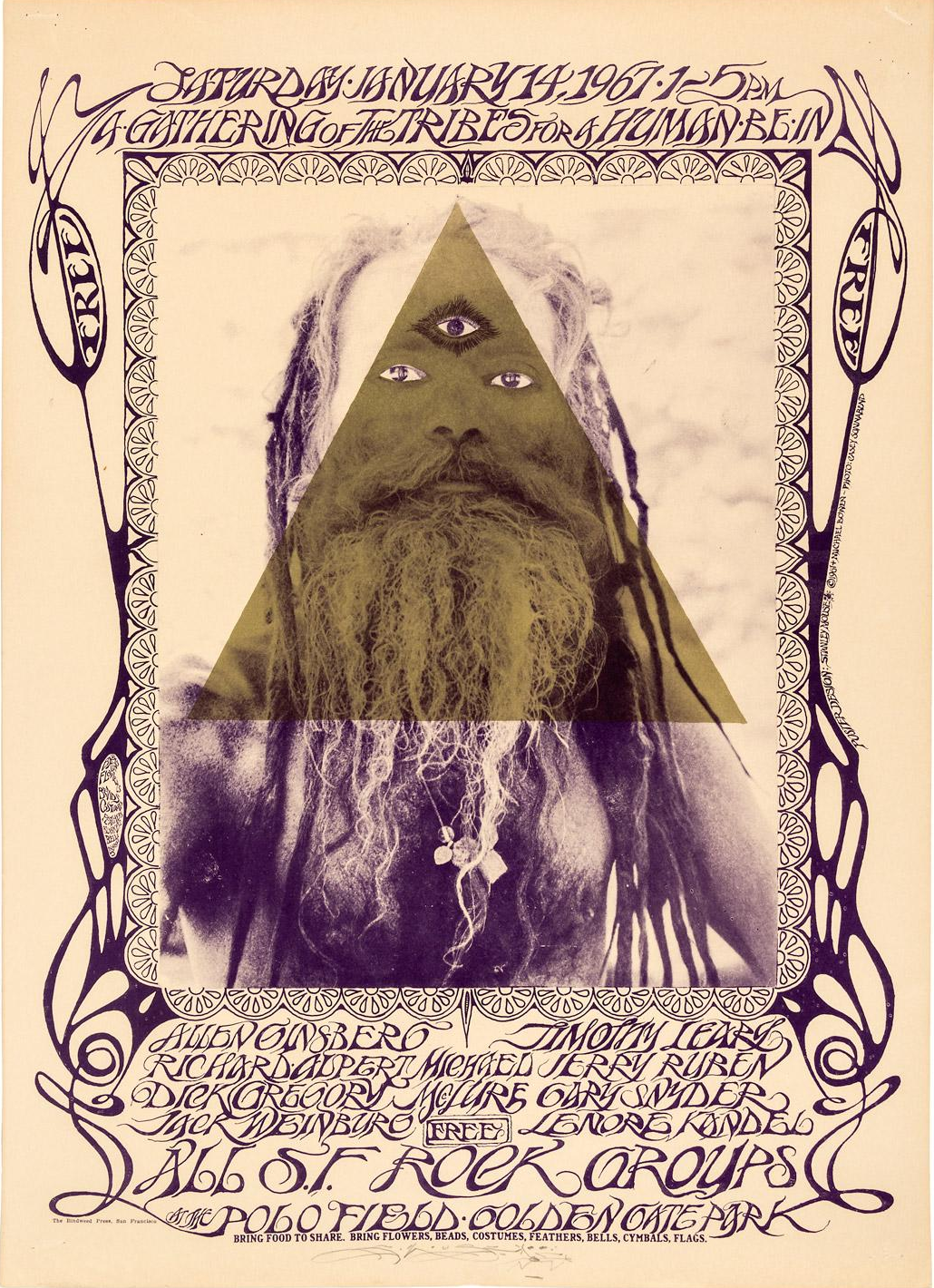

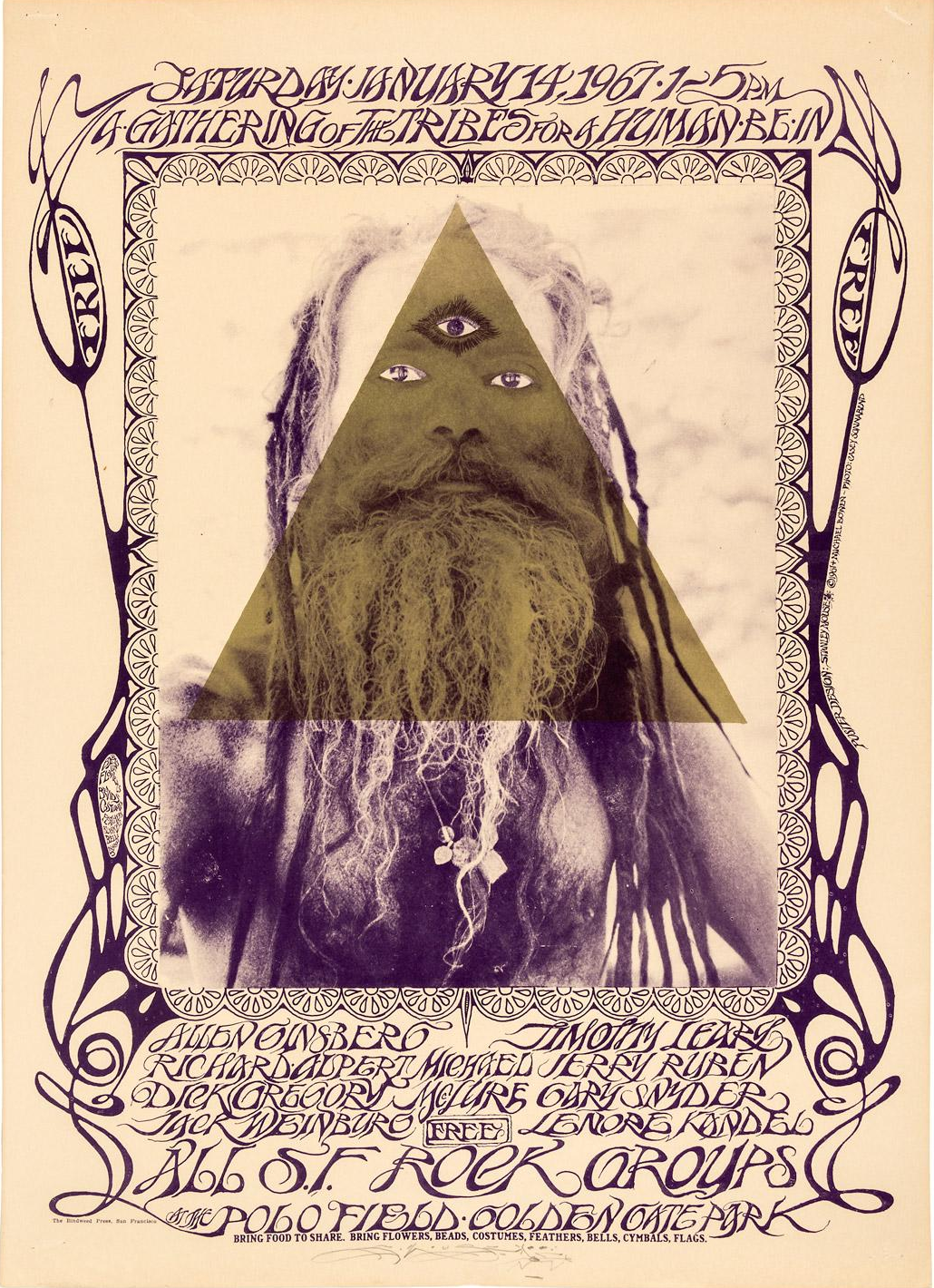

It would be easy to dismiss the play as a performance of Timothy Leary's admonition to "Turn on, tune in, drop out," and to say the "core" message is "ignore all the rules; just enjoy yourselves."

Poster for the Human Be-In at Golden Gate Park in 1967.

And while there's plenty to support that claim–lots of sex and drugs and, every time things get a bit too serious, Berger makes crude jokes–there's something deeper as well. The hippies wrestle with politics, survival, and their sense of self. They try to find their own identities in a community that's aggressively cooperative, in contrast with the large society that seeks to erase them.

For all the fun and festivities, there is a dark undertone that cannot be banished by any amount of song and merriment. As the story pushes toward the conclusion Claude fears so deeply, he is left with the awareness that, while his community will share his joys, they don't know how to lessen his worries or sorrows. We, the audience, are stuck also realizing that these cheerful, carousing people, who hug freely and seem devoid of jealousy or malice, are fighting an unwinnable battle against forces they do not wish to comprehend, because even naming the foe would lose the innocence that allows their tribe to exist at all.

Five stars. The highs are lively and charming, and the lows are breathtakingly bleak.

</small

</small

![[March 22, 1970] Fashion: The Mystical is Going Mainstream](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Mama-Cass-the-Fool-HAIR-party-1-672x372.png)

![[July 8, 1968] Let the Sunshine In (<i>Hair: The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/680708_HairAlbum-600x372.jpg)