[if you’re new to the Journey, read this to see what we’re all about!]

by Gideon Marcus

There's a war going on in our nation, a war for our souls.

No, I'm not referring to the battle of Democracy versus Communism or Protestants against Catholics. Not even the struggle between squares and beatniks. This is a deeper strife than even these.

(from Fanac)

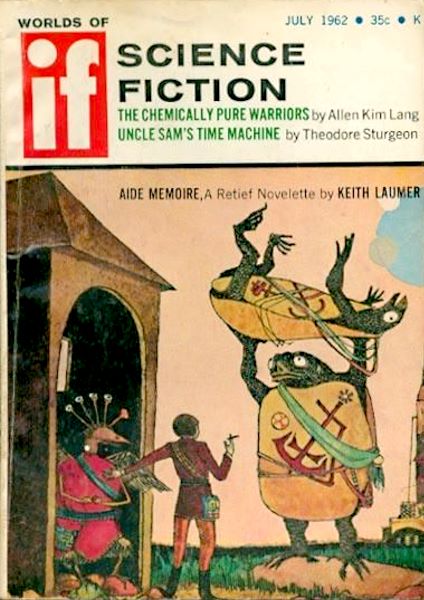

I refer, of course, to the schism that divides science fiction fans. In particular, I mean the mainstream fans and the literary crowd. The former far outnumber the latter, at least if the circulation numbers for Analog compared to that of Fantasy and Science Fiction are any indication.

Devotees of editor Campbell's Analog, though they occasionally chide the editor's obsession with things psychic, appreciate the "hard" sf, the focus on adventure, and the magazine's orthodox style it has maintained since the 1940s. They have nothing but sneering disdain for the more literary F&SF, and they hate it when its fluffy "feminine" verbosity creeps into "their" magazines.

F&SF, on the other hand, has pretentions of respectability. You can tell because the back page has a bunch of portraits of arty types singing the magazine's praises. Unfortunately for the golden mag (my nickname – cover art seems to favor the color yellow), many of the writers who've distinguished themselves have made the jump to the more profitable "slicks" (maintstream magazines) and novels market. This means that editor Davidson's mag tends to be both unbearably literate and not very good.

This is a shame because right up to last year, I'd sided with the eggheads. F&SF was my favorite digest. On the other hand, I'm not really at home with the hoi polloi Campbell crowd. Luckily, there is the middle ground of Pohl's magazines, Galaxy and IF.

Nevertheless, there is still usually something to recommend F&SF, particularly Dr. Asimov's non-fiction articles, and the frequency with which F&SF publishes women ("feminine" isn't a derogatory epithet for me.)

And in fact, if you can get past the awful awful beginning, there's good stuff in the August 1962 F&SF:

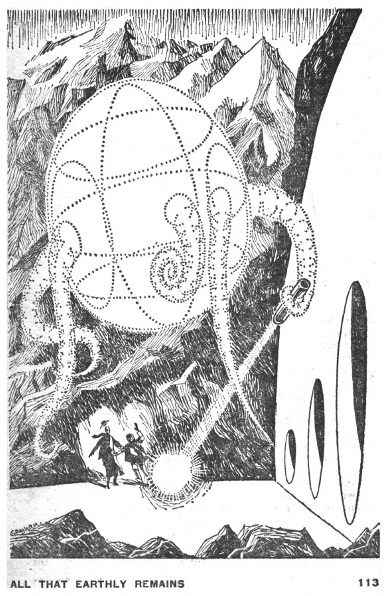

The Secret Songs, by Fritz Leiber

Leiber is an established figure in the genre, having written some truly great stuff going back to the old Unknown days of the 30s. He even won the Hugo for The Big Time. However, Secret Songs, a tale of a drug addled Jack Sprat and wife with countering addictions, won't win any awards. It's not sf, nor is it very interesting. I give it two stars for creative execution and nothing else.

The Golden Flask, by Kendell Foster Crossen

Boy, is this one a stinker. Not only does Davidson ruin it with his prefatory comments (I've stopped reading them – they are too long by half, inevitably spoil the story, and are never fun to read), but the gotcha of this bloody tale is puerile. One star.

Salmanazar, by Gordon R. Dickson

Some obtuse tale of the macabre involving magic, Orientalism, and a sinister cat. Gordy Dickson is one of the better writers…when he wants to be. He didn't this time. One star.

The Voyage Which Is Ended, by Dean McLaughlin

When the century-long trip of a colony ship is over, crew and passengers must struggle with the dramatic change in role and responsibilities. This somber piece reads like the first chapter of a promising novel that we'll never get to read. I did appreciate the theme: a ship's captain isn't necessarily best suited to lead a polity beyond a vessel's metal walls. Three stars.

Mumbwe Jones, by Fred Benton

A vignette of undying friendship between a White trader and an African witch-doctor…and the vibrant world of sentient creatures, animate and otherwise, with which they interact. An interesting piece of magic realism a little too insubstantial to garner more than three stars.

The Top, by George Sumner Albee (a reprint from 1953)

Career ad-man receives the promotion he's always desired, allowing him at last to meet the President of the sprawling industrial combine of which the copywriter is just a valuable cog. But does the Big Boss run the machine, or are they one and the same? Another piece that isn't science fiction, nor really worth your time. Two stars.

The Light Fantastic, by Isaac Asimov

The good Doctor's piece on electromagnetic radiation is worth your time. He devotes a few inches to the brand new "LASERS," artificially pure light beams that stick to a single wavelength and don't degrade with distance. I've already seen several articles on this wonder invention, and I suspect they will make them into a clutch of sf stories in the near future.

By the way, the cantankerous has-been Alfred Bester has finally turned in his shingle, resigning from the helm of the book review department. In an ironic departing screed, he lamented the lack of quality of new sf (not that he's contributed to that body of work in years), and states that people shouldn't have been so sensitive to his criticisms. To illustrate, he closes with the kind of anti-womanism we've come to expect from Bester:

"A guy complained to a girl that the problem with women was the fact that they took everything that was said personally. She answered, 'Well, I sure don't.'"

Good riddance, Alfred. Don't let the turnstile bruise your posterior.

Fruiting Body, by Rosel George Brown

I always look forward to Ms. Brown's whimsical works, and this outing does not disappoint. When mycology and the pursuit of women intersect, the result is at once ridiculous, a little chilling, and highly entertaining. That's all I'll give you, save for a four-star rating.

The Roper, by Theodore R. Cogswell and John Jacob Niles

Some pointless doggerel whose meaning and significance escapes this boor of a reader. One star.

Spatial Relationship, by Randall Garrett

Ugh. How to keep two space pilots cramped in a little spaceship for years from killing each other? Give them phantom lovers, of course. I liked the story much better when it was called Hallucination Orbit (by J.T.McIntosh), and could well have done without the offensive, anti-queer ending. You'll know it when you see it. Two stars.

The Stupid General, by J. T. McIntosh

Speaking of J.T.McIntosh… The literature is filled with if-only stories where peace-loving aliens are provoked to violence by the hasty actions of a narrow-minded general. But what if the fellow's instincts are right? A good, if not brilliant, story. Three stars.

What Price Wings?, by H. L. Gold

This is the first I've heard from Galaxy's former editor in a couple of years – I have to wonder if this is something that was pulled from an old drawer. Anyway, a classic tale of virtue being its own punishment. It ends predictably, but it gets there pleasantly. Three stars.

Paulie Charmed the Sleeping Woman, by Harlan Ellison

Many years ago, on a lark, I translated the classic story of Orpheus and Eurydice from an Old English rendition. Now, in his first appearance in F&SF, Mr. Ellison presents a translation of the tale into hepcat jive. It's an effective piece, though heavier on atmosphere than consequence. Three stars.

The Gumdrop King, by Will Stanton

The issue ends with a fizzle: a youth meets an alien, and incomprehensibility ensues. I'm not sure that was the result Stanton was aiming for. Two stars.

Through Time and Space with Ferdinand Feghoot: LIII, by Grendal Briarton

Oh, and the Feghoot pun this time is just dreadful. Not in a good way.

Good grief. Doing the calculations, we find this issue only got 2.4 stars. It's definitely a favorite for worst mag of the month, and indicative of momentum toward worst mag of the year. Those philistines who subscribe to Analog are going to win after all…

(P.S. Don't miss the second Galactic Journey Tele-Conference, July 29th at 11 a.m.! You'll have a chance to win a copy of F&SF – not this issue, I promise!)

—