[Don't miss your chance to get your copy of Rediscovery: Science Fiction by Women (1958-1963), some of the best science fiction of the Silver Age. If you like the Journey, you'll love this book (and you'll be helping us out, too!)

by Cora Buhlert

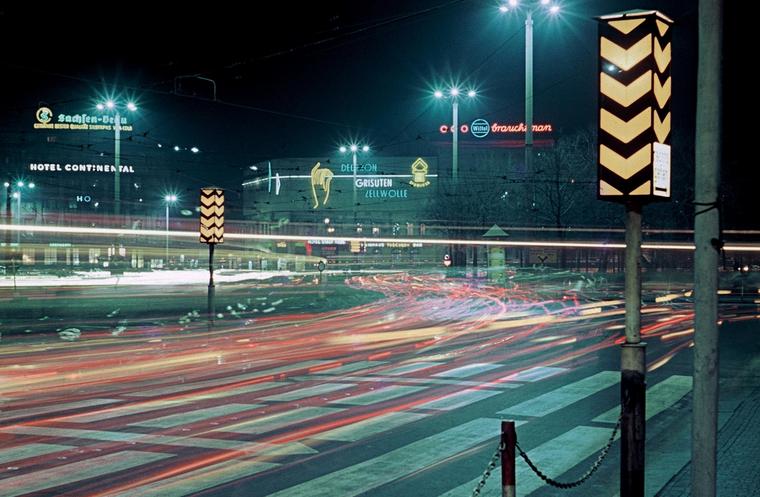

Here in Germany, the Iron Curtain just got a tiny hole, because since November 2, East German pensioners are allowed to visit friends and family in the West. In the first few days, hundreds of elderly people availed themselves of the opportunity to see loved ones they had’t seen in years.

Nobody is under any illusion that this is anything but a propaganda coup for East German leader Walter Ulbricht. Pensioners are considered more of a burden than an asset to the so-called German Democratic Republic, so the East German state does not mind if they decide to stay in the West. But the many families who are finally reunited do not much care about Ulbricht’s political machinations – they are just happy to see their loved ones again.

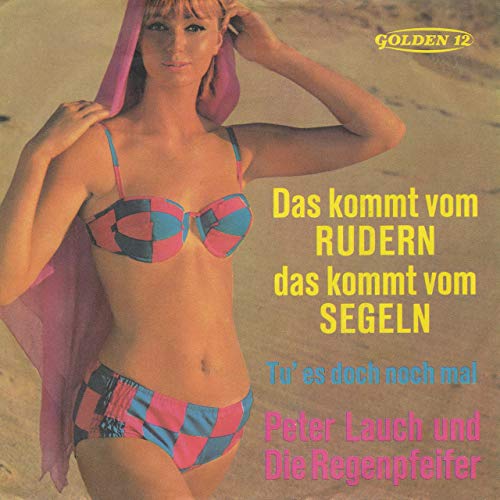

Meanwhile on the music front, the West German charts have been dominated by a curious song called "Das kommt vom Rudern, das kommt vom Segeln" (That's from rowing, that's from sailing) by Peter Lauch & die Regenpfeifer, a band which has made its name with mildly risqué novelty songs. Hint, the lyrics are not really about rowing and sailing, but about other physical activities in which adults engage. Personally, I find the song rather silly, but it has clearly hit a nerve, because it was playing all over this year's Freimarkt, the annual autumn fair which has been held in my of my hometown of Bremen since 1035 AD. Yes, you read that correctly. This year was already the 929th Freimarkt.

The Freimarkt has changed a lot in the past 929 years. In fact, it has even changed a lot in the past ten years. The technology of fairground rides is improving steadily and new rides are debuting every year. This year, we even had two space themed rides, the rocketship ride Titan and Sputnik, a spectacular ride where a tilting ring of cars orbits a globe that represents the Earth. Both rides are a lot of fun and probably as close as an ordinary human like me will get to outer space in the foreseeable future.

Checking in on Perry Rhodan

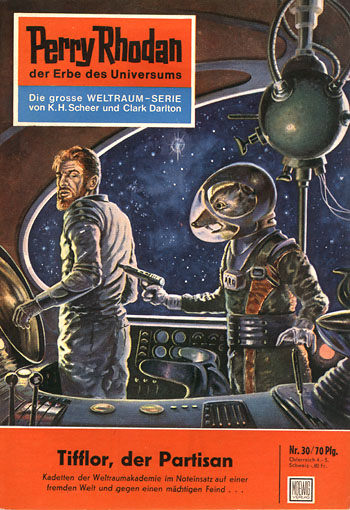

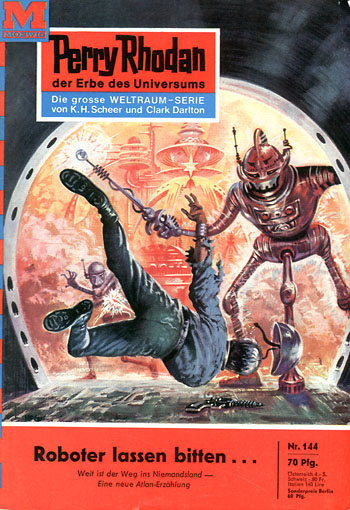

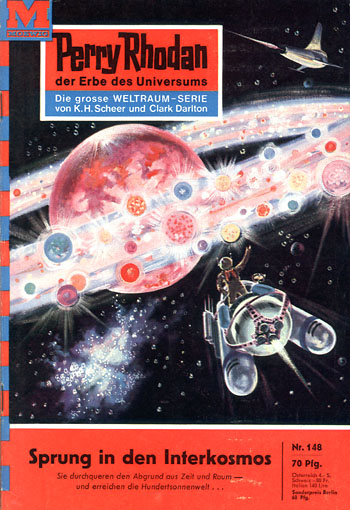

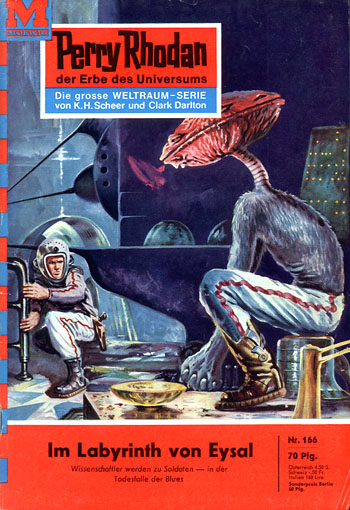

Talking of outer space, it has been more than a year since I last discussed Perry Rhodan, Germany’s most popular science fiction series. So it’s high time to check in on Perry again to see what he’s been doing this past year.

Quite a lot, it turns out. Since the Heftroman issues of Perry Rhodan are published weekly now, the plot moves at a brisk clip. Furthermore, a monthly companion series of so-called Planetenromane (planet novels), 158 page paperback novels, premiered in September. The third issue just came out. Many Heftromane have paperback companion series, but most of them just republish old material, occasionally by literally stapling unsold issues together and adding a new cover. The Planetenromane, on the other hand, offer all-new stories, often side stories, which don't quite fit into the main series.

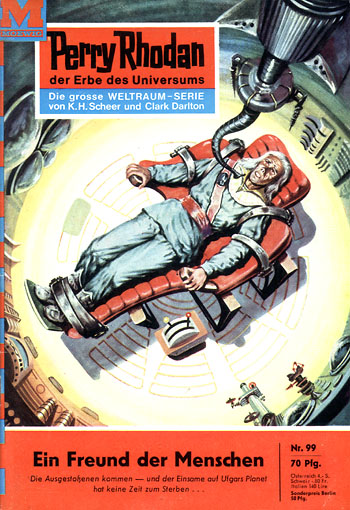

The lives of Perry Rhodan and his friends remained busy in the regular series as well. Perry Rhodan in particular had to deal with a series of personal losses. First, his Arkonian wife Thora, a mainstay of the series since issue 1, died last year. Next, another character who has been in the series since the very first issue, Perry's friend and brother-in-law, the Arkonian Crest, heroically gave his life in issue 99.

A Universe With Too Few Women

Particularly, the loss of Perry's wife Thora in issue 78 is still keenly felt after more than a year, because Thora was one of the few female characters in the male-heavy Perry Rhodan universe. There are women in the Mutant Corps that Perry Rhodan founded, a female intelligence agent named Fraudy Nicholson who fell in love with her target played an important role in a recent mini plot-arc and there are other women guest characters as well, but Thora was the only consistent female presence in the series.

Of course, Perry Rhodan is immortal and so it is to be expected that he would eventually move on. And indeed, he gradually fell for Akonian scientist Auris von Las-Toór, whom he met in issue 100. Auris also developed feelings for Perry, even though they found themselves on different sides during a conflict with the Akon. And when Auris finally deserted her family and homeworld to be with Perry, she was killed in the ensuing battle in issue 125.

Perry Rhodan's tendency to kill off its few female characters is troubling, especially since half of the cast is immortal. Though it has to be said that quite a few male characters were also built up, sometimes over several issues, only to be unceremoniously killed off. Perry Rhodan fans have taken to calling this practice "voltzen" after writer William Voltz in whose stories this frequently happens.

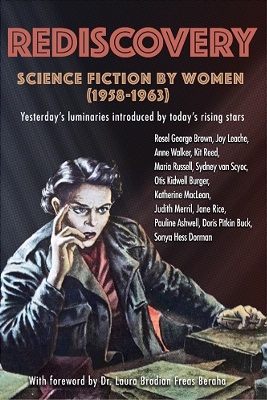

What Perry Rhodan really needs is some women on its writing staff, which currently is all male. Perry Rhodan co-creator Walter Ernsting a.k.a. Clark Dalton frequently translates stories by female American science fiction authors, so he isn't averse to science fiction written by women at all. So why doesn't he invite some German woman writers to join the Perry Rhodan staff? Plenty of women read Perry Rhodan, so it would only be fair of some of them got to write for the series.

A Family Tragedy

Being related to Perry Rhodan is clearly a risk to your health, as the example of Perry and Thora's estranged son Thomas Cardif shows, for Thomas became increasingly hostile and tried to depose his father. I was not a huge fan of the Thomas Cardif story arc, if only because Cardif's initial motivation is only too understandable. After all, Thomas Cardif was raised in secret, not knowing who his parents were, supposedly for his own safety. And once he learns the truth, Thomas blames Perry Rhodan for his difficult childhood, not entirely without reason. After his first attempted coup, Perry Rhodan orders Thomas Cardif's memories hypnotically wiped (because keeping him in ignorance of his true origin worked so well the first time). As a result, Thomas becomes even angrier when he recovers his memories and goes on a worse rampage than before. He even captures and impersonates his father for a while. Thomas eventually dies of old age, when his cellular activator, the device which grants Perry Rhodan and his close associates immortality, fails.

The story of Thomas Cardif is a tragedy, but a preventable one. Furthermore, our hero Perry Rhodan does not come off at all well in this story arc, because his bad parenting decisions were what caused Thomas to go rogue in the first place. Conflicts between a parent generation still steeped in the propaganda of the Third Reich and a younger generation that demands the truth about all the ugly history that was swept under the rug are currently playing out all over Germany, so it is only natural that a series as popular as Perry Rhodan would reflect that conflict. However, the overwhelmingly young readers did not expect that Perry Rhodan of all people would side with the reactionary parent generation.

Thomas Cardif was not the only one who challenged Perry Rhodan's rulership over the Solar Empire. A group calling itself the Upright Democrats was also disenchanted with Perry's policies and tried to assassinate him. Naturally, Perry survived – he is immortal, after all – and had the malcontents exiled to a distant planet, where they tangled with friendly and hostile aliens for several issues.

In fact, Perry Rhodan introduced several new alien species over the course of the last year, such as the invisible Laurins (named after the invisible dwarf king of medieval legend) and the duplicitous Akonians, who are distant ancestors of the generally benevolent Arkonian race, hence the very similar (and confusing) names. Another welcome new addition to the series are the positronic-biological robots, Posbis for short, a cyborg race that lives on planet with one hundred (artificial) suns. The Posbis were initially hostile towards the humanity, but eventually became close allies after Perry Rhodan reprograms their brains.

No article about Perry Rhodan would be complete without recognizing artist Johnny Bruck, who has created every Perry Rhodan cover as well as all interior illustrations and spaceship schematics to date. His sleek spaceships, futuristic cityscapes, quirky alien creatures such as the fan favourite character Gucky, the mouse beaver, and – when the plot allows – beautiful women have contributed a lot to Perry Rhodan's success. Bruck is a true phenomenon, not just West Germany's best science fiction artist, but one of the best in the world. Unfortunately, his work is little known outside the German speaking world, but I hope that he will eventually receive the international recognition he deserves.

Quo Vadis Perry Rhodan?

Johnny Bruck's covers are one of the few constants in a series that is in a period of transition, as unceremoniously killing off long-term characters such as Thora and Crest shows. The writing team headed by co-creators Clark Dalton and K-H. Scheer has well and truly outrun their initial outline for a series of fifty Heftromane by now. This is also why Perry Rhodan has felt somewhat disjointed of late, focussing on mini-arcs which last for a couple of issues each and sometimes don't include Perry or any of the other main characters at all. It is obvious that the writers are experimenting, introducing new characters and concepts, while looking for a new direction for the series as a whole. In fact, issue No. 166, which came out this week, doesn't feature any of the main characters and introduces yet another new alien race.

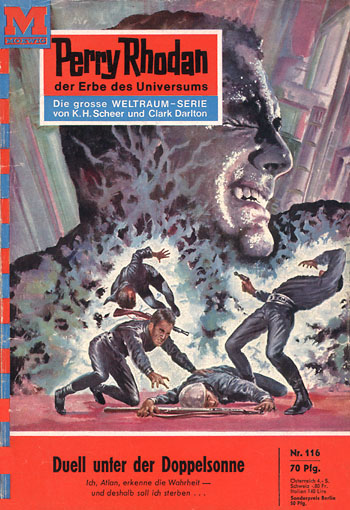

The most successful of the newly introduced characters is Atlan, an ancient Arkonian who crash-landed on Earth in prehistoric times and spent millennia asleep in a dome under the ocean, waking every couple of centuries to protect and guide humanity. During his latest awakening, Atlan not only learned that humans had become a spacefaring civilisation in the meantime and even made contact with his own people, he also encountered Perry Rhodan. After some initial misunderstandings, Perry Rhodan and Atlan became close friends – after all, they both share the same goal, to protect humanity.

Since his introduction in issue 50, the character of Atlan quickly became a fan favourite, to the point that the covers frequently announce "A new Atlan Adventure", even though the series itself is still named Perry Rhodan. The popularity of Atlan is also part of the reason why longterm series mainstays such as Crest and Thora were written out. And indeed, Atlan has pretty much taken over the role as Perry Rhodan's alien best friend that was once filled by Crest. I am not as enamoured with Atlan as many other readers seem to be and also wonder why Perry cannot have more than one Arkonian friend. But the character of Atlan is clearly here to stay and has become an intrinsic part of the series, as Perry Rhodan searches for a new direction that will take it to issue 200 and beyond.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[November 5, 1964] The State of the Solar Empire: <i>Perry Rhodan</i> in 1964](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/PR0107-350x372.jpg)

![[September 26, 1964] A Mystery Mastermind Double-Feature: The Ringer and The Death Ray of Dr. Mabuse](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/hexer-499x372.jpg)

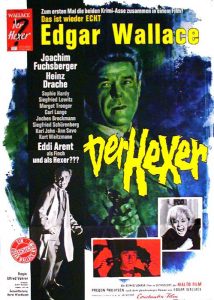

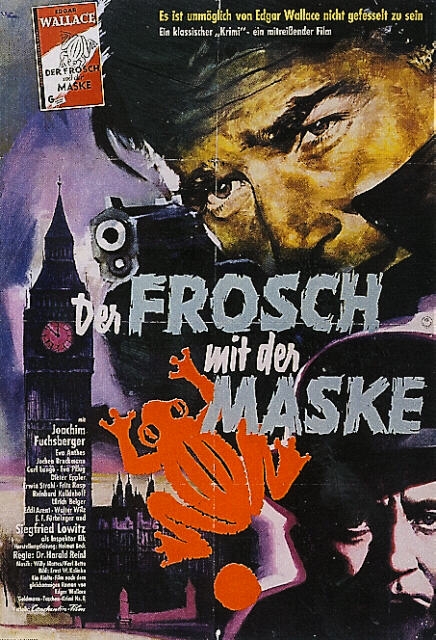

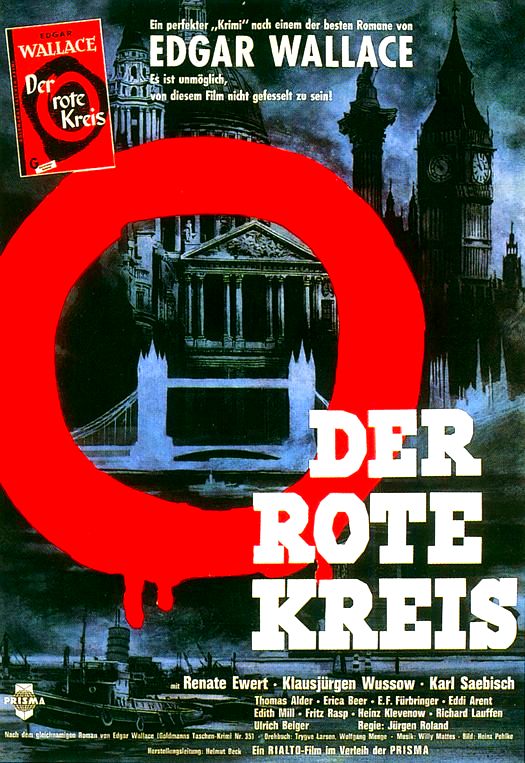

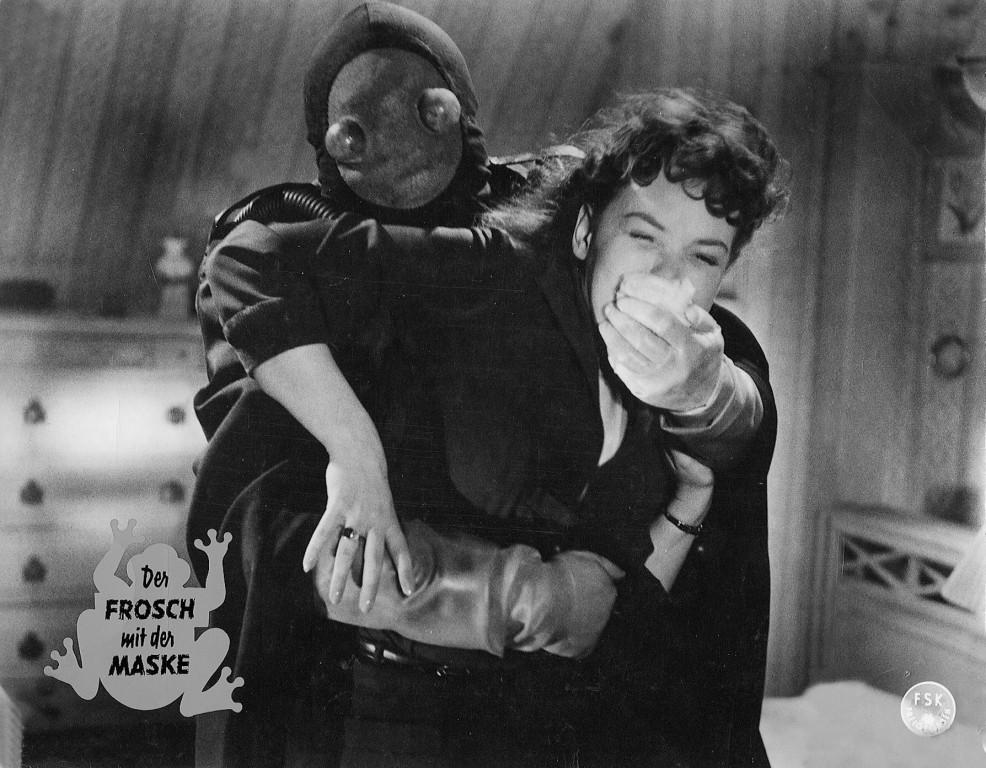

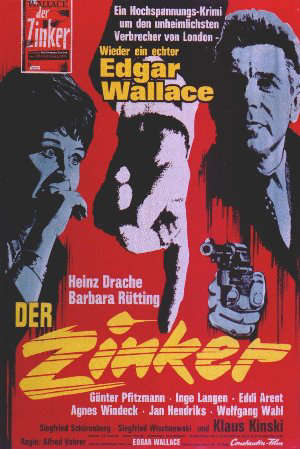

Der Hexer (The Ringer) is the twentieth Edgar Wallace adaptation produced by Rialto Film and one of the best, if not the best movie in the series so far. The Ringer is a pure delight and a distillation of everything that has made the Edgar Wallace series so successful. The balance of humour and thrills is just right and The Ringer will have you both rolling on the floor with laughter and on the edge of your seat with suspense. There are nefarious crimes, a mysterious figure – for once not the villain – whose true identity is not revealed until the final reel and a twisting and turning plot that still has a twist or two in store, even after the Ringer has been unmasked.

Der Hexer (The Ringer) is the twentieth Edgar Wallace adaptation produced by Rialto Film and one of the best, if not the best movie in the series so far. The Ringer is a pure delight and a distillation of everything that has made the Edgar Wallace series so successful. The balance of humour and thrills is just right and The Ringer will have you both rolling on the floor with laughter and on the edge of your seat with suspense. There are nefarious crimes, a mysterious figure – for once not the villain – whose true identity is not revealed until the final reel and a twisting and turning plot that still has a twist or two in store, even after the Ringer has been unmasked. The Ringer is based on Edgar Wallace's 1925 novel The Gaunt Stranger and its 1926 stage version The Ringer, though the literal translation of the German title would be "The Witcher". It's certainly apt, for the titular character is not just a master of disguise, but also has nigh sorcerous abilities to evade Scotland Yard's finest.

The Ringer is based on Edgar Wallace's 1925 novel The Gaunt Stranger and its 1926 stage version The Ringer, though the literal translation of the German title would be "The Witcher". It's certainly apt, for the titular character is not just a master of disguise, but also has nigh sorcerous abilities to evade Scotland Yard's finest. Unbeknownst to the killers, the murdered woman was Gwenda Milton, the younger sister of Arthur Milton, the vigilante known only as the Ringer for his uncanny ability to disguise himself as anybody he pleases. Years ago, Arthur Milton had given up his career of vigilantism and retired to Australia, far beyond the reach of the British law. But now he is back to take revenge on the murderers of his sister. Of course, both the villains and Scotland Yard are only too eager to capture the Ringer. There is only one problem. No one knows what he looks like.

Unbeknownst to the killers, the murdered woman was Gwenda Milton, the younger sister of Arthur Milton, the vigilante known only as the Ringer for his uncanny ability to disguise himself as anybody he pleases. Years ago, Arthur Milton had given up his career of vigilantism and retired to Australia, far beyond the reach of the British law. But now he is back to take revenge on the murderers of his sister. Of course, both the villains and Scotland Yard are only too eager to capture the Ringer. There is only one problem. No one knows what he looks like.

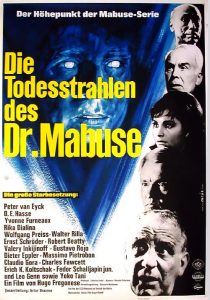

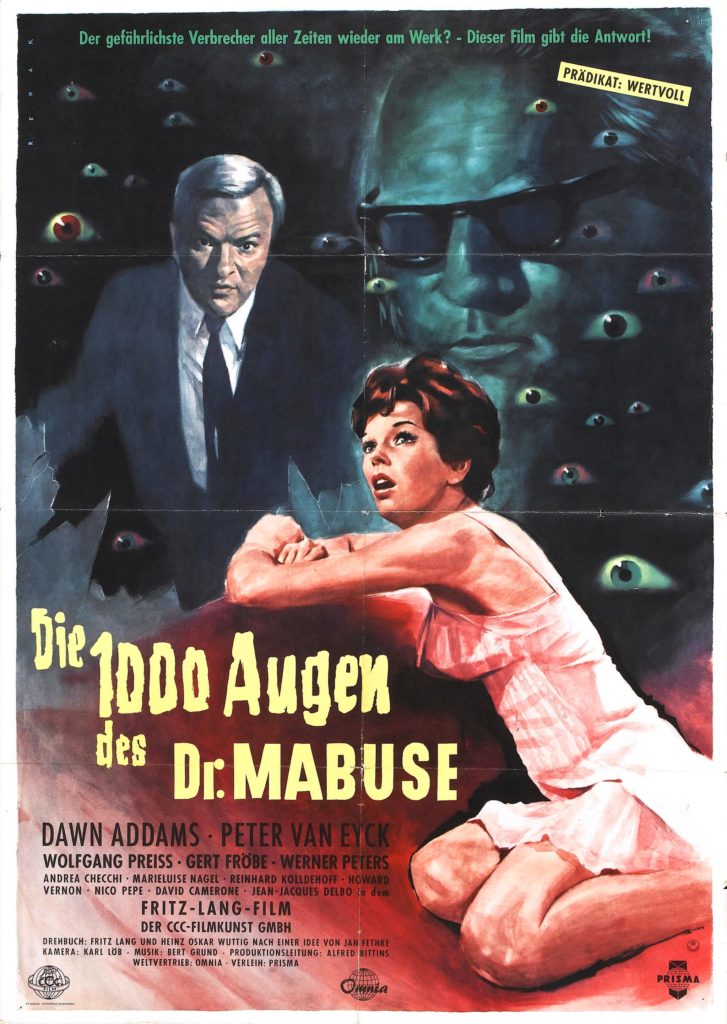

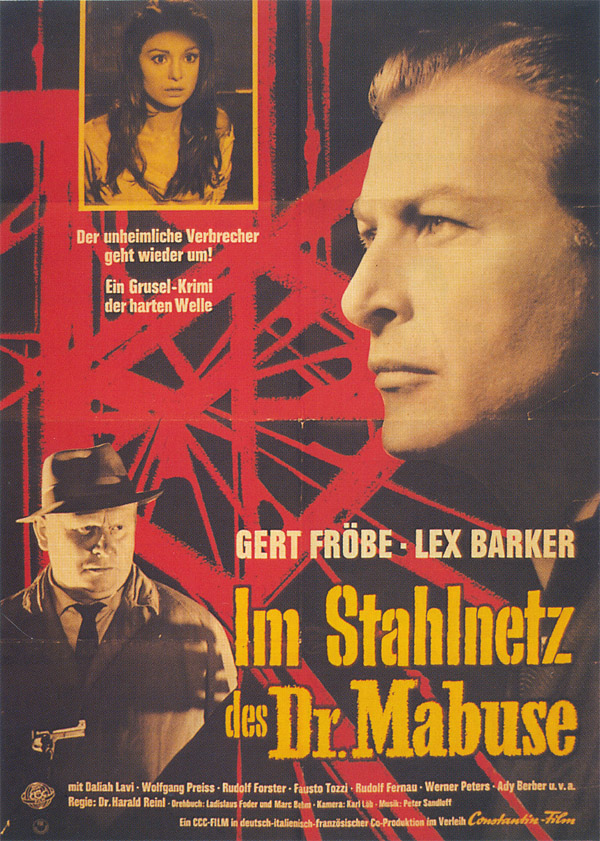

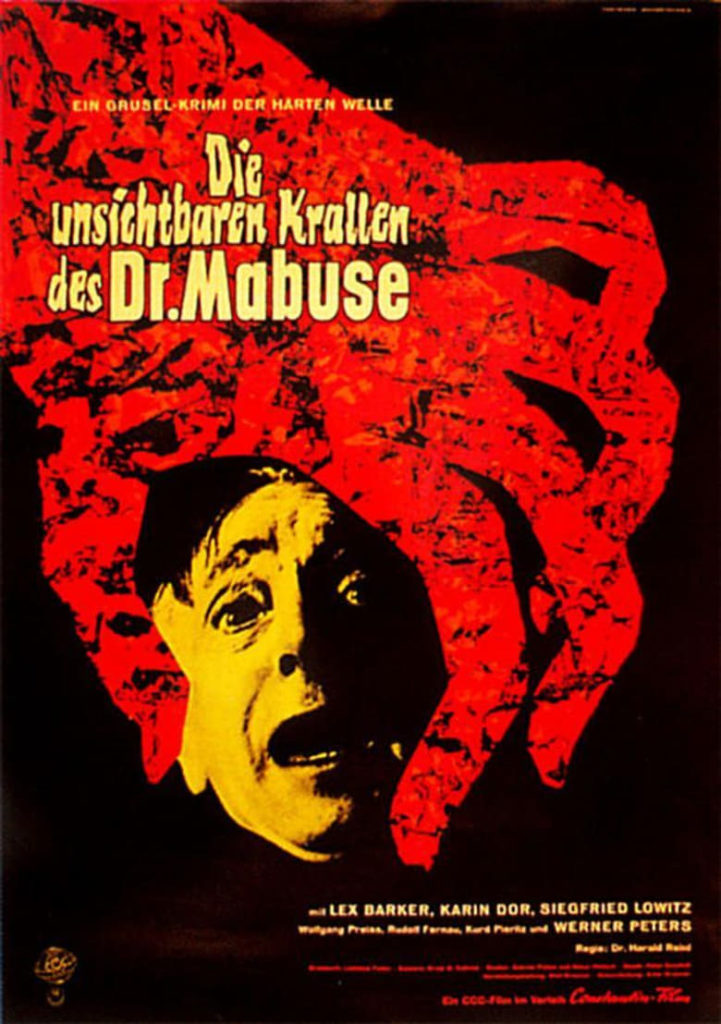

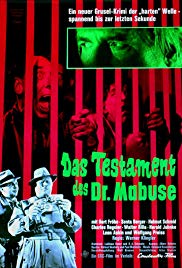

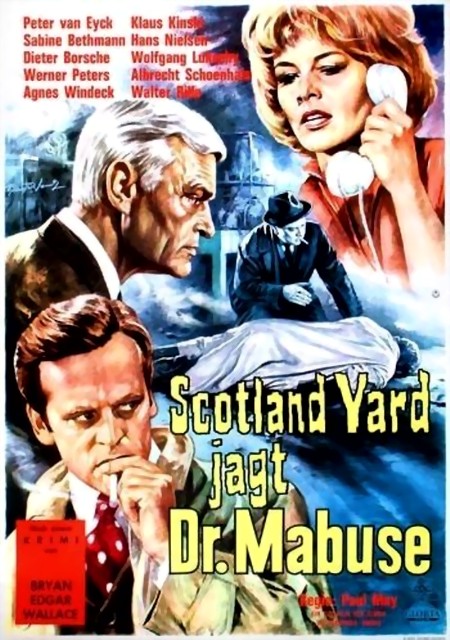

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the latest movie in the other great West German thriller series. For while the Dr. Mabuse series has been very good at reinventing itself in the five movies made post WWII (plus two made during the Weimar Republic) so far, the latest instalment Die Todesstrahlen des Dr. Mabuse (The Death Ray of Dr. Mabuse) shows definite signs of the series going stale.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the latest movie in the other great West German thriller series. For while the Dr. Mabuse series has been very good at reinventing itself in the five movies made post WWII (plus two made during the Weimar Republic) so far, the latest instalment Die Todesstrahlen des Dr. Mabuse (The Death Ray of Dr. Mabuse) shows definite signs of the series going stale.

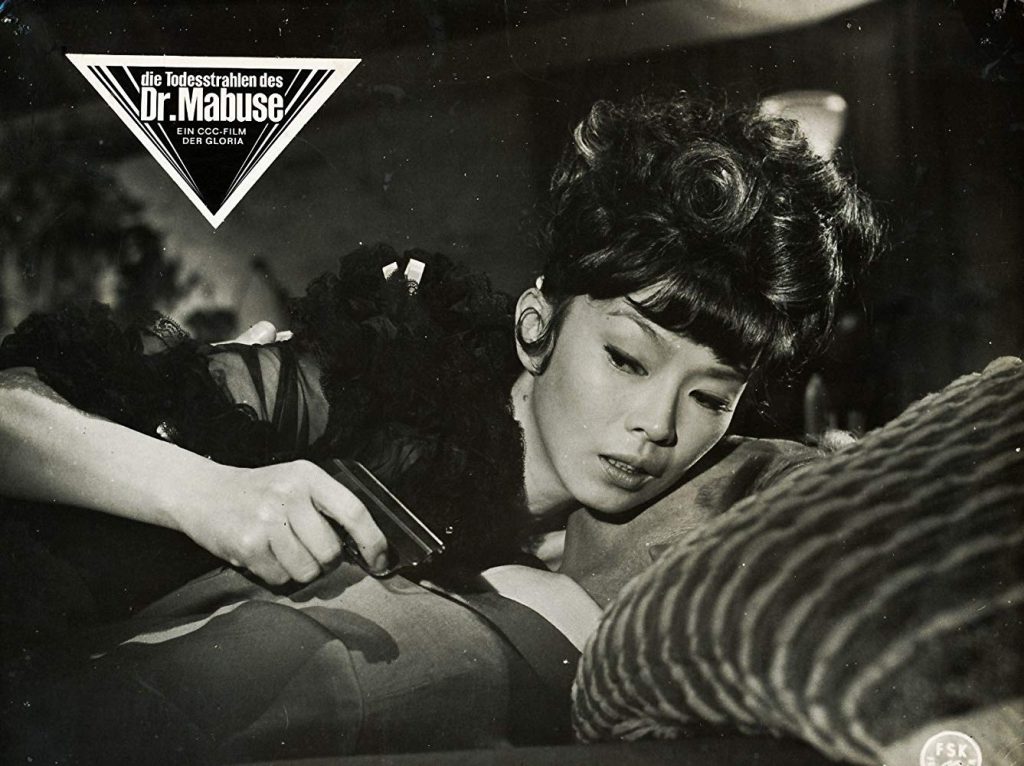

Not long after Pohland's disappearance, Anders is given a new assignment – to investigate spy activities in Malta, where a scientist named Professor Larsen is working on an invention that will change the world. And that invention just happens to be a death ray. Anders no more thinks that this is a coincidence than the audience does. So he hastens to Malta, taking along Judy (former Miss Greece Rika Dialina), one of his many girlfriends, to pose as a newlywed couple on their honeymoon.

Not long after Pohland's disappearance, Anders is given a new assignment – to investigate spy activities in Malta, where a scientist named Professor Larsen is working on an invention that will change the world. And that invention just happens to be a death ray. Anders no more thinks that this is a coincidence than the audience does. So he hastens to Malta, taking along Judy (former Miss Greece Rika Dialina), one of his many girlfriends, to pose as a newlywed couple on their honeymoon.

![[July 8, 1964] The Immortal Supervillain: The Remarkable Forty-Two Year Career of Dr. Mabuse](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Testament-1933-386x372.jpg)

![[June 4, 1964] Weird Menace and Villainy in the London Fog: The West German Edgar Wallace Movies](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640604The_Green_Archer-672x372.jpg)

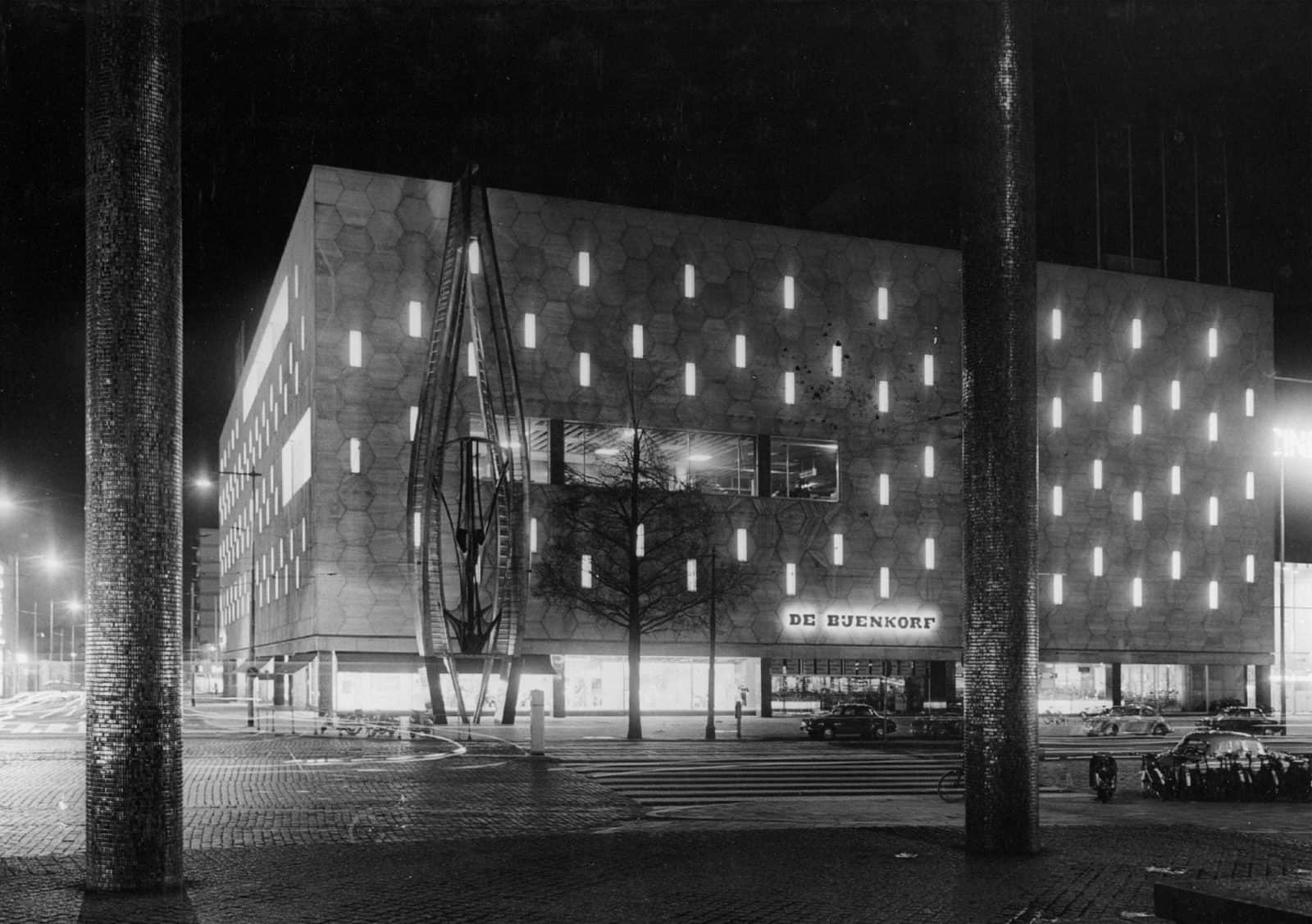

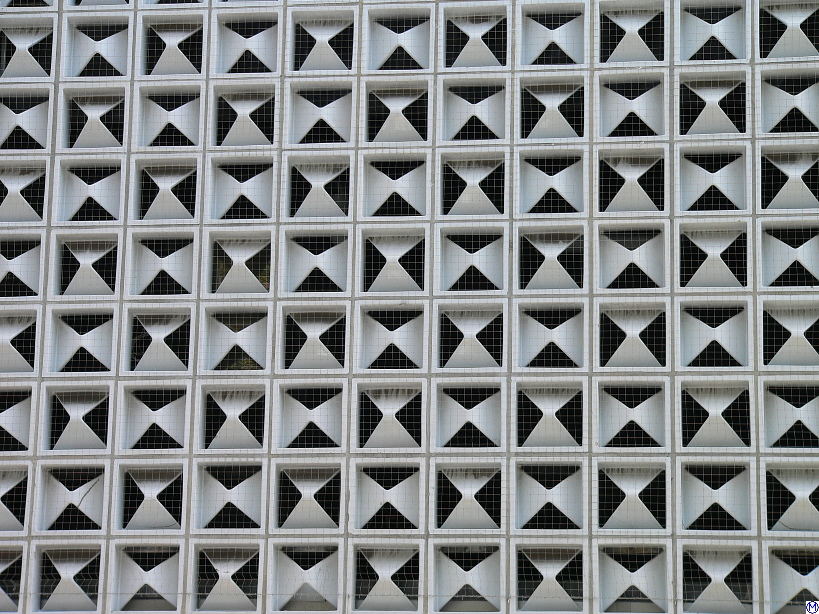

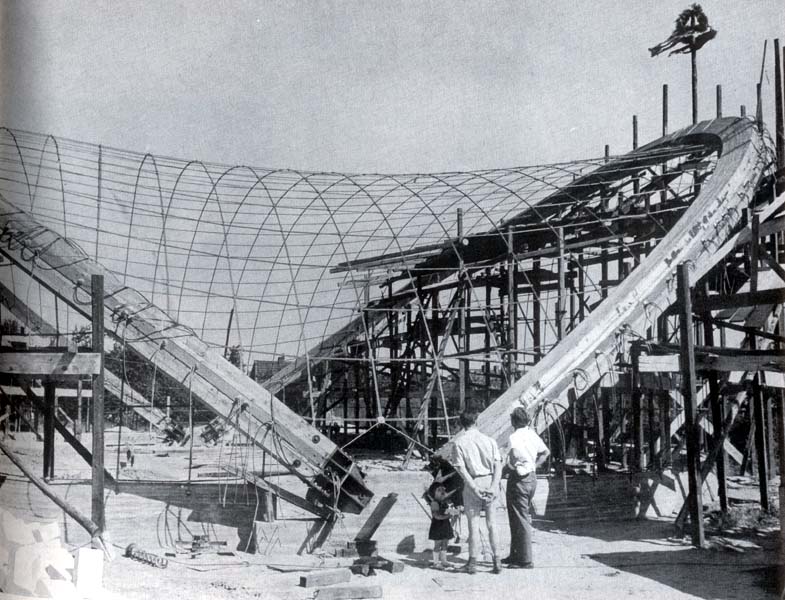

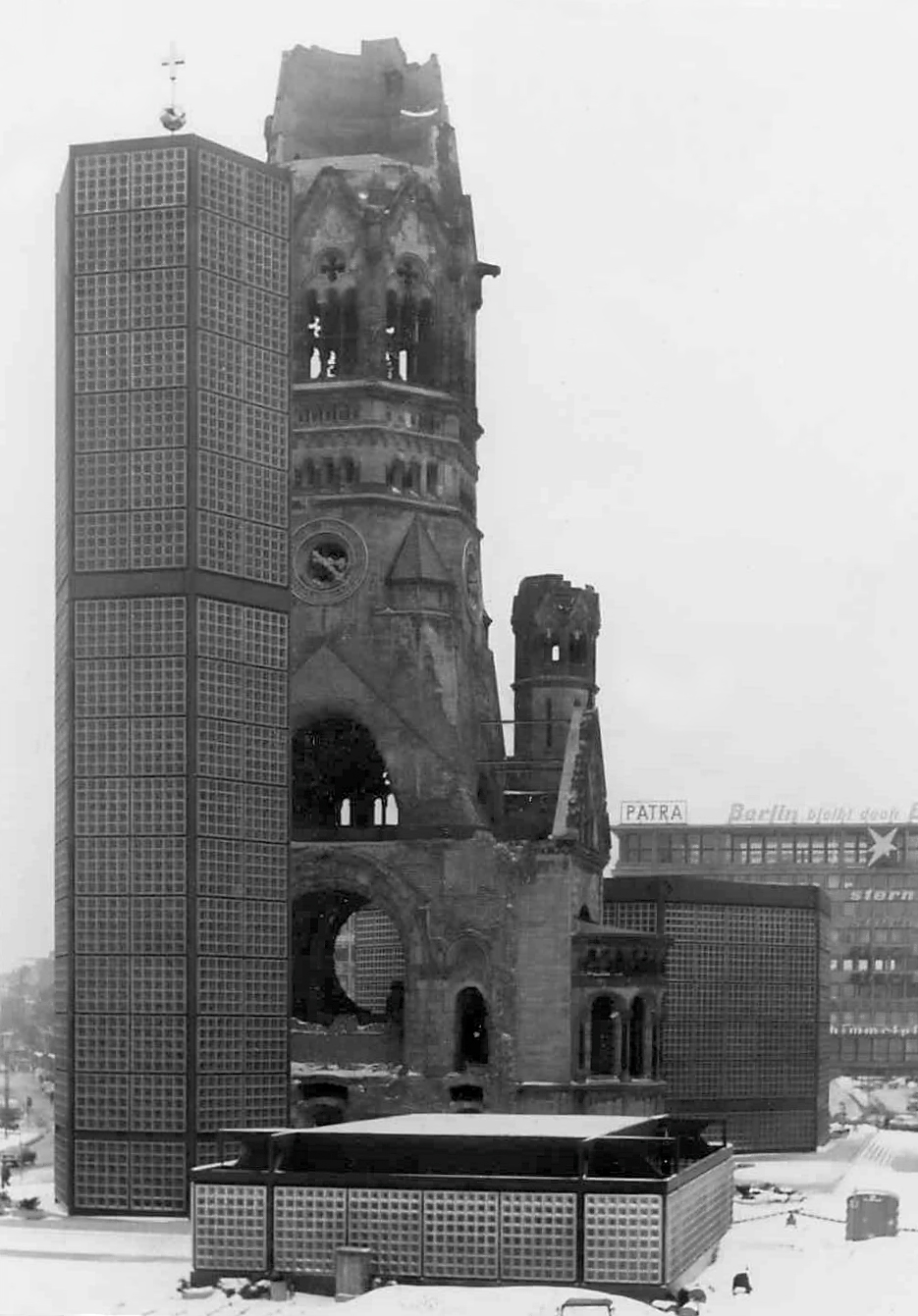

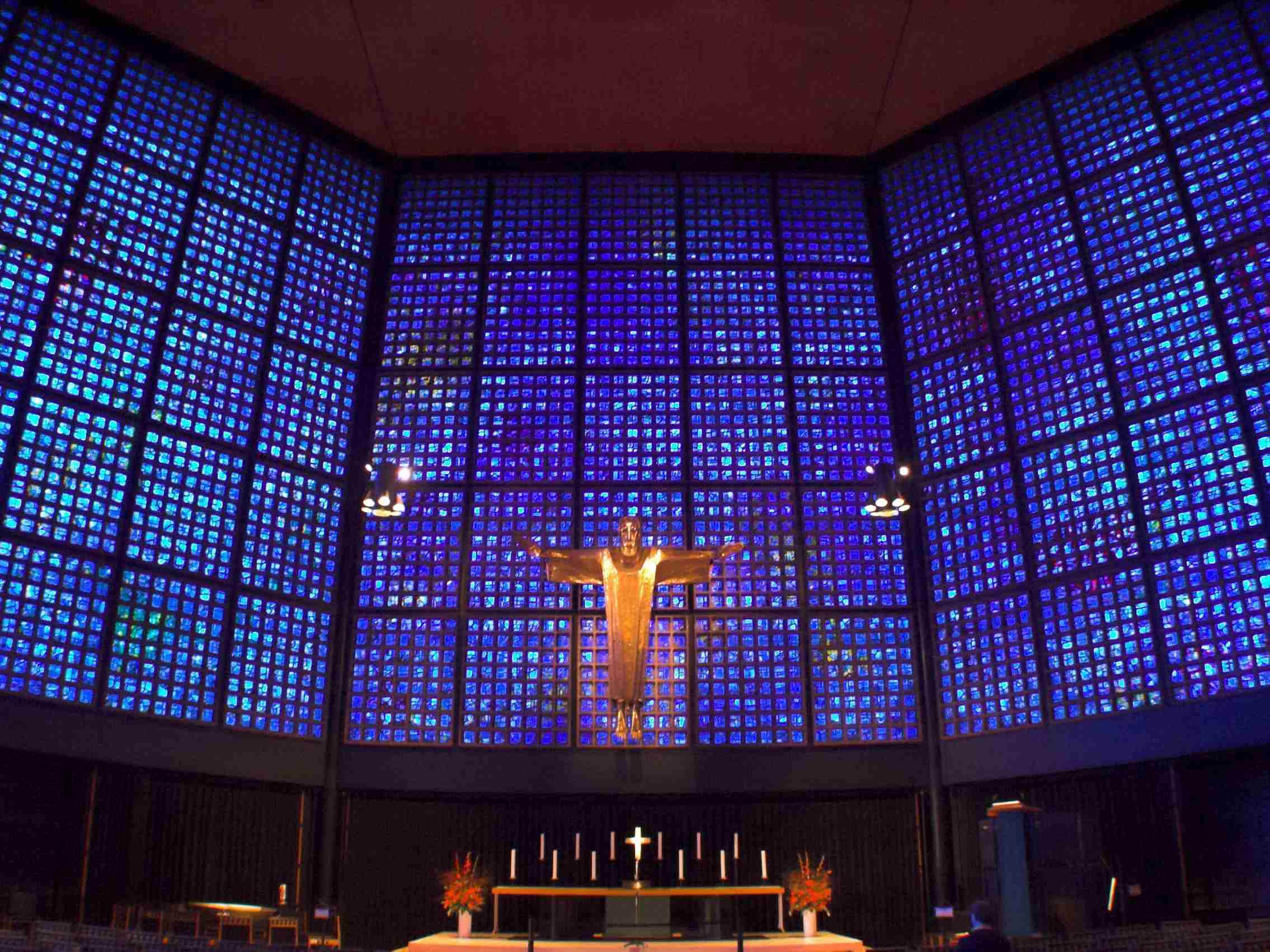

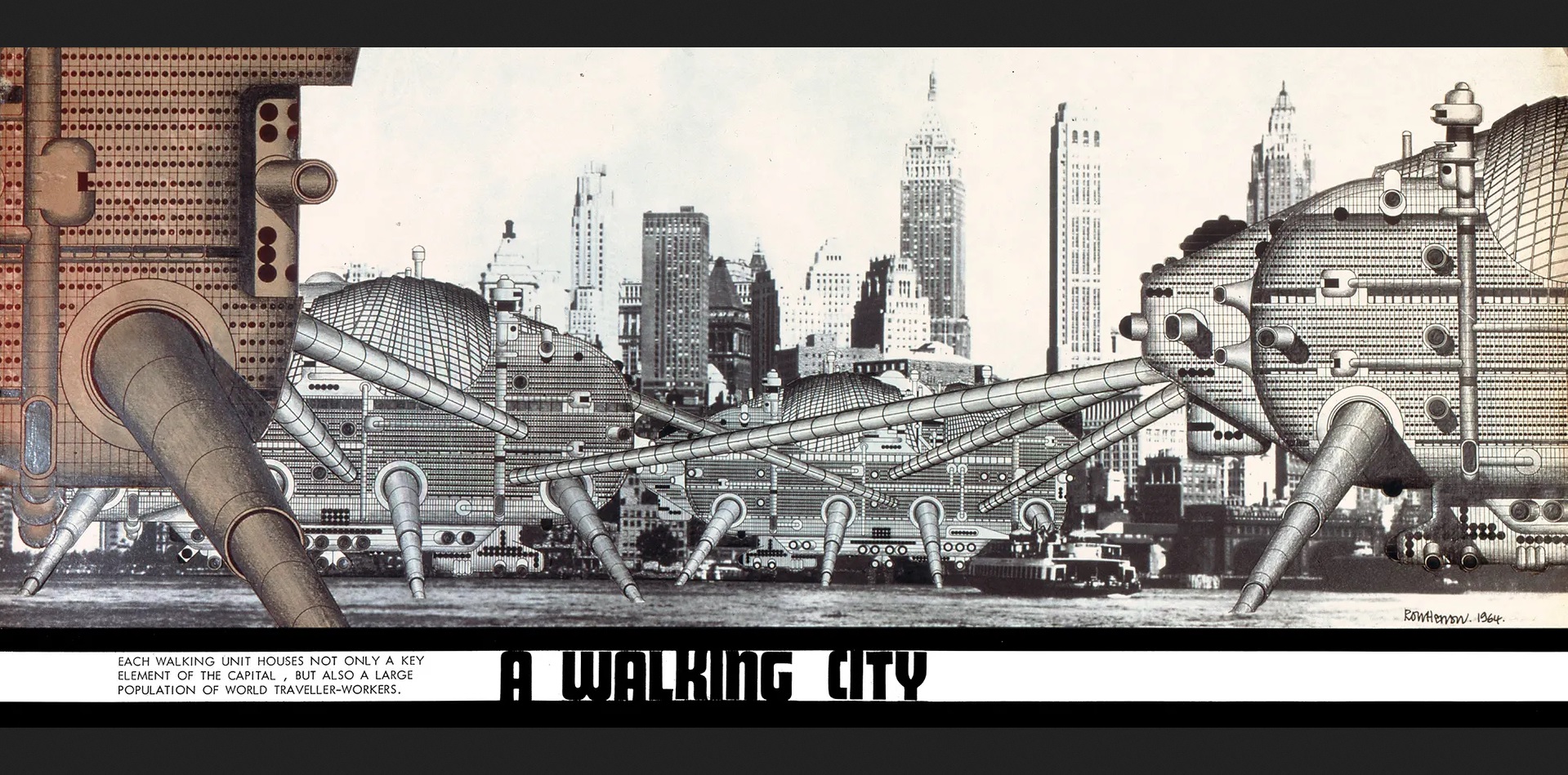

![[March 21, 1964] Building the City of the Future upon Ruins: A Look at Postwar Architecture in Germany, Europe and the World](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640321Kongresshalle_Berlin-607x372.jpg)

![[November 24, 1963] Mourning on two continents](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631123Flowers_Schoeneberger_Rathaus-672x372.jpg)

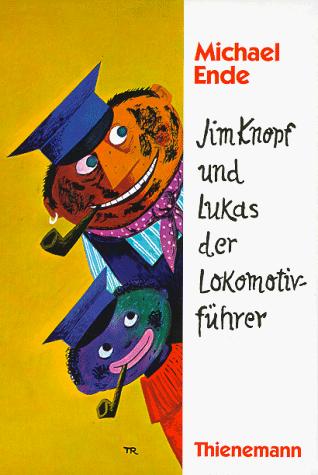

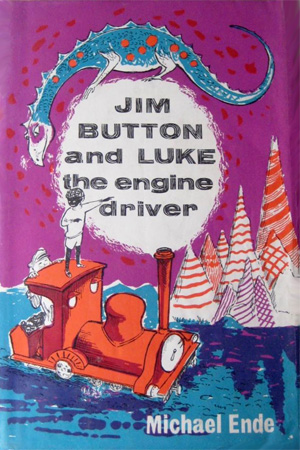

![[Oct. 30, 1963] <i>Jim Knopf and Lukas the Train Engine Driver</i> by Michael Ende: A Classic in the Making](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631030Cover_Jim_Knopf_English.jpg)

![[September 15, 1963] <i>The Silent Star</i>: A cinematic extravaganza from beyond the Iron Curtain](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630915German_poster-672x372.jpg)