Happy Thanksgiving!

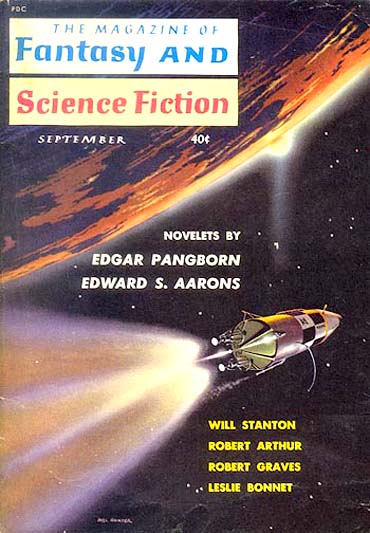

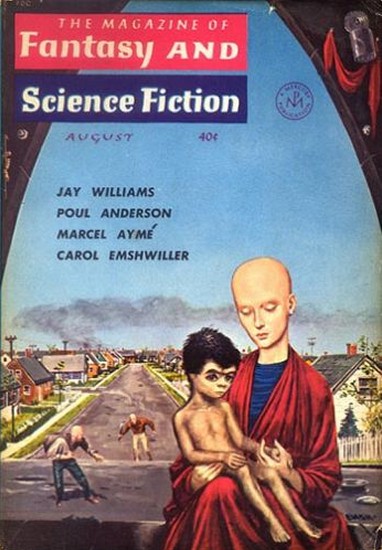

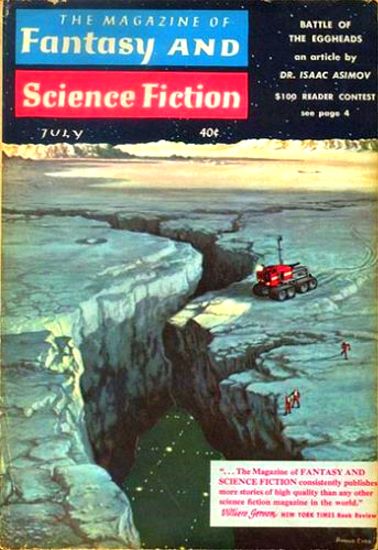

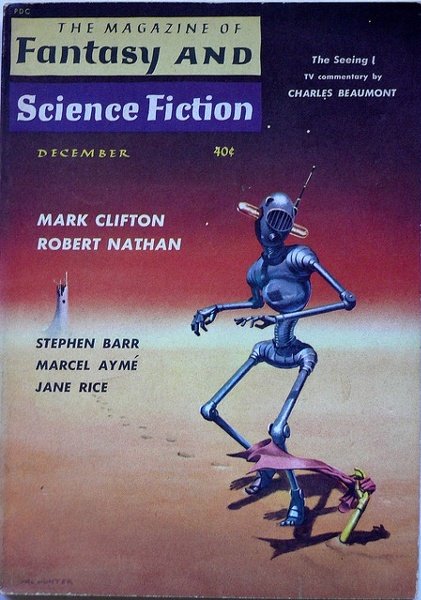

This season, we have much to be thankful for, but I am particularly thankful that I ended this publishing year on a high note—the December Fantasy and Science Fiction.

If anything could get out the taste left by this month's Astounding, particularly the Garrett story, it's F&SF. In this case, the lead novelette, What now, little man? by Mark Clifton, was the indicated antidote.

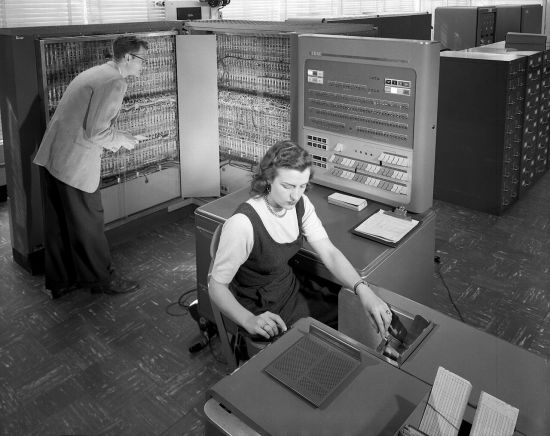

Clifton addresses the issue of racial abuse head on with this excellent tale. On a distant mining colony, humans have only one native source of food—the bipedal, humanoid "Goonie." When the colony was first inhabited, the Goonies were deemed unintelligent by human standards. They seemed to have no culture, and they let themselves be slaughtered without so much as a peep of protest.

Then they proved to be trainable. At first, they performed simple beast-of-burden chores, but over time, they learned more sophisticated skills. By the time of the story, many can read and write, and one exceptional example can perform as an accountant.

This tale is that of a man wracked with conscience. This farmer, who was the first to train a Goonie to perform advanced mathematical services, is convinced that the slaughter of Goonies is wrong. To champion this cause, he is willing to put his life on the line, though it turns out that a female sociologist from Earth employs better, non-lethal methods to effect change, or at least to set the world on the course of change.

The protagonist, and the reader, are left with the fundamental questions: What defines intelligence? Who defines intelligence? Can one justify making the definition so rigid as to exclude members of one's own race? And what do the Goonies represent? True pacifists? The ultimate survivors?

Good stuff. Four stars.

Dr. Asimov has another fine article, this one on the layers of the Earth's atmosphere. It's well timed, perhaps on purpose, as I'd just read a scholarly article on a new revised atmospheric model. We've learned a lot in just three years of satellite launches.

I've never heard of Gerard E. Neyroud. His Terran-Venusian War of 1979, in which Venus conquers the Earth with love, but subsequently devolves into civil war, is glib and fun, if rather insubstantial.

Marcel Aymé has another cute short translated from the French. The State of Grace is about an (un)fortunate fellow whose saintliness is blessed with a halo only a few decades into his life. This quickly becomes a terrible annoyance to his wife, who begs him to do something about it. His solution: to sin like there's no tomorrow. Yet, no matter how far he indulges himself in the seven deadly sins, he cannot rid himself of the damned thing. The moral is, apparently, piety will out, even when covered in degradation.

Stephen Barr's The Homing Instinct of Joe Vargo is chilling stuff, indeed. An expedition to a mining planet finds a truly unbeatable creature. Ubiquitous, cunning, and virtually indestructible, "It" is a translucent blob that kills by extruding threads of incredible strength, constricting its prey, and slicing it alive.

Only one fellow, the eponymous Joe Vargo, is able to survive thanks to equal parts wisdom and luck. The ending of the story is unnecessarily downbeat, and also implausible. As with Poul Anderson's Sister Planet, one can excise the coda and come away with a perfectly satisfying story.

Jane Rice has another good F&SF entry with The Rainbow Gold. Told in folksy slang, it is the story of a somewhat magical (literally) yokel family and their quest to secure that legendary pot of gold at the end of a rainbow. It's a lot of fun, and it has a happy ending.

damonknight has, perhaps, the best line of the issue in his monthly book column. Writing of Brian Aldiss, he says, "If the writer ever does a novel with his right hand, it will be something worth waiting for."

The Seeing I is Charles Beaumont's new column on science fiction in the visual media. In this installment, he details at length his involvement with the new show, The Twilight Zone. It's an absolutely fascinating read, and it just goes to show that things of quality can still be made, on purpose, so long as people are willing to invest the time and energy into the endeavor.

Finally, we have Robert Nathan's A Pride of Carrots, written as a radio play. That's because it actually was a radio play a couple of years ago on CBS. The prose has been substantially embellished, but it's largely the same story. At least, I think it is. I'm afraid fell asleep during the last act of the radio show.

I won't spoil the plot, save that it involves the planet Venus, two warring states peopled by vegetables, two visitors from Earth, and an interracial love triangle.

But is it good, you ask? Well, it's silly. It's not science fiction, but it is occasionally droll. Try it, and see what you think.

That wraps up the year. I'll be compiling my notes to determine which stories will win Galactic Stars for 1959. I'll make an announcement sometime next month.

In the meantime, enjoy your turkey. I'll have more for you soon.

Note: I love comments (you can do so anonymously), and I always try to reply.

P.S. Galactic Journey is now a proud member of a constellation of interesting columns. While you're waiting for me to publish my next article, why not give one of them a read!

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has comments. Please comment here or there.