by Erica Frank

Our external freedom is expanding daily. We are developing ever more powerful technology, with bold goals such as flying to the moon and someday the stars; the human race has a tremendous talent for turning potential into reality. Because of this, psychedelic research goes hand-in-hand with traditional science studies; as the introduction to this journal says: "We can no longer accept the notion of a value-free science or espouse a naive optimism with regard to scientific and technological progress. We need to complement our technical skill in controlling the external world with a corresponding development of our inner resources."

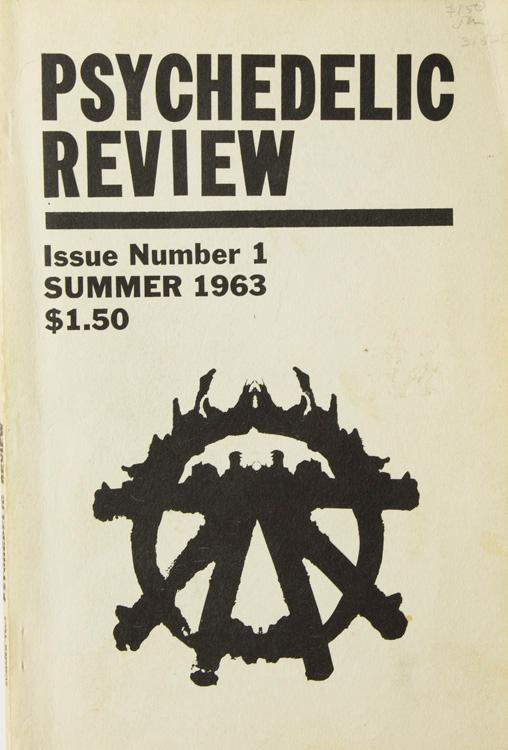

Doctor Timothy Leary has joined Ralph Metzner to found a new academic journal: the Psychedelic Review. The first issue was released in June, and I believe it's very relevant to the Journey. The Review's purpose is studying psychedelic substances like LSD, psilocybin and mescaline, in order to enhance "the individual's control over his own mind, thereby enlarging his internal freedom."

It's dense reading, very much an academic journal aimed at philosophers, historians, and medical professionals. I am none of these, but the articles are still fascinating to me (and hopefully, to you, too!)

"Can This Drug Enlarge Man's Mind?", Gerald Heard

Gerald Heard is an esteemed philosopher with multiple books in that field, and the the author of science fiction books The Doppelgangers and The Lost Cavern.

The drug in question is LSD, short for Lysergic Acid Diethylamide – no wonder everyone uses the initials! The editors mention the controversy surrounding the drug: its detractors say it warps minds, while its proponents claim it inspires creativity and perhaps even wisdom. It is agreed, however, that it is not habit-forming nor physically toxic.

Heald describes the subjective effects of LSD, as reported by its users: it produces "a profound change in consciousness… You see and hear this world, but as the artist and musicians sees and hears." This shift in awareness, a kind of hyper-sensitivity to the world, often also brings a new awareness of the self; Heard compares this to a passage in the Odyssey, which differentiates between two types of thought: those from "the Gate of Horn," relating to events of the real world, and those from the "Gate of Ivory," the source of fantasy. LSD brings ideas from the latter, which are so intense that they can result in profound changes like those of a deep religious experience. He points out that the drug does not create personality changes; the experience only awakens the potential; he recommends more research find the full value of LSD in psychoanalysis and the creative arts.

Worth reading for the combination of internal reports and external description of the LSD experience.

This reviews and combines the results of four questionnaires filled out by people who have experienced LSD or psilocybin mushrooms in psychiatric settings. Most people claimed it was a positive experience; only a scant handful believe it harmed them. Many now noticed a deeper significance to various aspects of life; some reported that the people close to them had noticed positive changes. Some benefits lasted for years after a single experience, such as alcoholics with longer periods of sobriety and fewer arrests.

The calculations were especially interesting, as they showed how to take an intensely subjective experience and describe it in a way that's useful for medical research. I am not convinced, however, that the psilocybin study should've been included, since it's a different substance and it involved student volunteers instead of psychiatric patients.

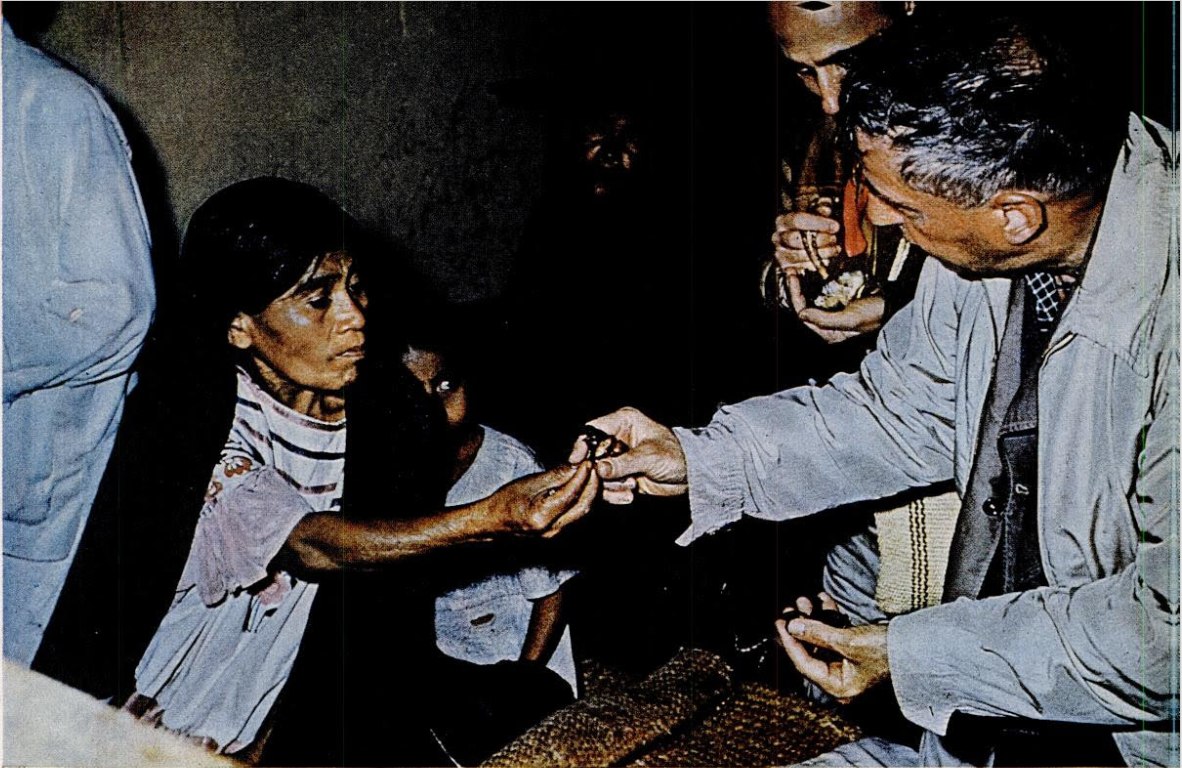

"The Hallucinogenic Fungi of Mexico: An Inquiry into the Origins of the Religious Idea Among Primitive Peoples", R. Gordon Wasson

Wasson and his wife studied the history of mushrooms across the world, looking through ancient texts in multiple languages, trying to figure out what role mushrooms played in folklore and history.

His research focuses on psychoactive mushrooms, and how they were used for ecstatic experiences, allowing the user to feel that the human soul has touched the divine. He mentions that we have no good ways to describe these experiences:

We are entering upon a discussion where the vocabulary of the English language, of any European language, is seriously deficient. There are no apt words in them to characterize your state when you are, shall we say, "bemushroomed." For hundreds, even thousands, of years we have thought about these things in terms of alcohol, and we now have to break the bonds imposed on us by the alcoholic association.

He traveled into the mountains of Mexico, regions where the old languages are still used and Spanish is rare (and of course, they've barely heard of English), and took mushrooms under the guidance of tribal shamans. The practical details were covered in "Seeking the Magic Mushroom," published in Life magazine a few years ago; this article focuses on the experience itself. He seems to be looking for words that does not exist, and so falls back on using several paragraphs to describe the sensations and realizations he had.

I found the linguistic aspects of this article more interesting than the philosophical considerations, although those were also intriguing.

"A Touchstone for Courage", Plato

This is an excerpt of a passage from Plato's The Laws. I have never done well with Plato. I agree with Clinias: "I fear I hardly follow you, yet pray proceed with your statement as though I did."

Plato mentions how potential courage is rarely fully developed because most people don't often face their fears. He then discusses the value of a hypothetical drug that could inspire fear, and allow people to overcome those fears without the physical risks that attend most challenges that require courage.

The implication is that even the unpleasant, darker experiences of LSD and related substances have value: they allow people to face their innermost fears, and if not conquer them, at least endure them, and realize the fear itself did not destroy them.

I can't tell if this is "Plato taken far out of context" or "exactly the kind of consideration he would've wanted to inspire."

"Provoked Life: An Essay on the Anthropology of the Ego", Gottfried Benn

Gottfried Benn was an expressionist poet and author; this essay was originally published in Germany in 1949 and is reprinted with permission; this may be the first English translation available to the public.

The essay is beautiful and intense… and I have no idea what it actually says. It reads like a longer, more detailed and personal version of the drug experiences described in the earlier articles. The purple prose makes it hard to follow; the essay is packed with exotic imagery and sensory overloads, enough that I couldn't decide if he was making a point or just pondering a set of ideas.

"The Individual as Man/World", Alan W. Watts

Alan Watts is a philosopher who strives to bring Buddhist concepts into mainstream, Western psychology. His works include The Way of Zen and The Joyous Cosmology: Adventures in the Chemistry of Consciousness. This article, originally a lecture delivered at Harvard, doesn't address psychedelics per se, but the personal experience of consciousness.

Watts points out that how people understand their own existence often does not match well with the descriptions taught in the sciences: a biologist's or ecologist's description of humanity bears little relation to human life as we experience it. Modern science is just as much a victim of cultural biases as the ancient Greeks, which presumed that all living things were distorted reflections of pure, abstract archetypes.

He discusses importance of considering people as a whole being, not a collection of parts, despite the current trends in medicine and psychology to reduce people to organ-based emotions and socially programmed impulses.

Watts is a delight to read. Even when he's explaining very complex concepts, he uses down-to-earth language that sets a foundation that builds them toward a single point of understanding. This is probably my favorite article in this issue.

"Annihilating Illumination", George Andrews

This is a poem in the Beat style: it does not rhyme; most lines don't begin with capital letters; they aren't of matching lengths; there is an utter lack of punctuation in this three-page poem, save for a single quoted sentence and the final period.

It reads like a shorter, less pompous version of "Provoked Life," and is therefore much more accessible, if not any more comprehensible.

While being struck by lightning in slow motion

the fire sears away layer after layer

sizzles me down to my ultimate ash

I quiver shrieks of laughing crystals

the radiant frenzy of the storm's soul dwells in the guts of the dragon

That's the beginning; it continues like that for three pages. I think I don't have access to the right drugs to enjoy this kind of poetry.

"The Pharmacology of Psychedelic Drugs", Ralph Metzner

This is the hard science article. It defines psychedelic substances as those "whose primary effect on human subjects is the radical alteration of consciousness, perception and mood", and outlines the criteria for the ones being included in this review. These include negligible somatic effects, no addictive qualities, and a specific history in psychiatric literature.

I confess, I skimmed this article. I am not a chemist, not a biologist; once they start dragging out the molecular structure charts, I can be entertained but not informed. I know enough chemistry to understand the raw meanings of the diagrams, but not enough to have any idea how those connect to the practice of medicine.

This article is 30 pages; the references are an additional 15. The tone is very different from the other articles. It's written by one of the editors; I wonder if they created the journal for the purpose of publishing this. It reads like a chemical study in a medical journal, of little interest to other fields. It's possible that psychiatrists would find value in it, but only for understanding the biological effects; this article lacks the humanizing approach of the others.

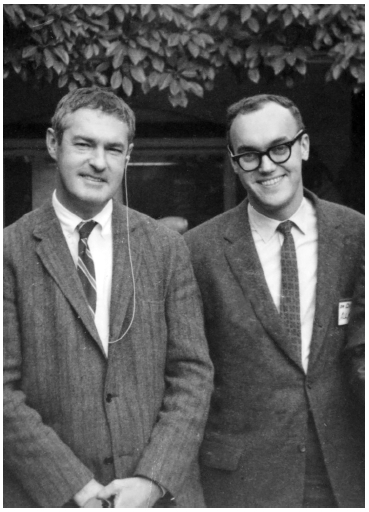

Dr. Timothy Leary and Dr. Richard Alpert, Harvard, 1961

If you read medical journals, Psychedelic Review may be right up your alley. Otherwise, it comes across as a heavy-handed attempt to insist that psychedelic substances are worthy of real scientific consideration. This is understandable, given the recent history of the editors.

In May of this year, just about the time this issue was published, Dr. Leary and Dr. Richard Alpert were fired from Harvard for involving students in psychedelic substance testing. While they committed no crimes in sharing LSD and psilocybin with students, they did violate university policy, which only allows such substances to be given to graduate students. In addition, the university claims Leary was not meeting his lecture requirements.

I suppose that means he'll have more time to focus on research; I look forward to future issues of the Psychedelic Review.

![[October 14, 1963] Take a little trip… (Timothy Leary's <i>Psychedelic Review</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631014psychrev1-1cvr-508x372.png)

![[September 7, 1963] Druids at College: An Old Religion for a New Era](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630907druids-672x372.jpg)