by Cora Buhlert

Today, I'm going to talk about a children's fantasy series that may well be a future classic. But first, I want to talk about politics. For since October 16, 1963, West Germany has a new chancellor.

Now West Germany does have a president, currently Heinrich Lübke, but he is a figurehead with little political power. The real power rests with the chancellor. And since 1949, there has only been one chancellor, Konrad Adenauer. However, his final term was beset by scandals and so Mr. Adenauer finally resigned at the ripe old age of 87.

I have to admit that I'm not a big fan of Konrad Adenauer. He did a good job rebuilding the country after WWII and his place in history is assured. But after fourteen years, it is time to let someone else have a go. The new chancellor, Ludwig Ehrhard, was secretary of economics in Adenauer's cabinet and is largely responsible for West Germany's so-called economic miracle. Therefore, I don't expect many changes, but maybe a somewhat younger government.

But now let's leave politics behind, because today I want to introduce you to a wonderful fantasy duology by up and coming author Michael Ende. Though marketed as children's books, these are books all ages can enjoy.

A most unusual visitor

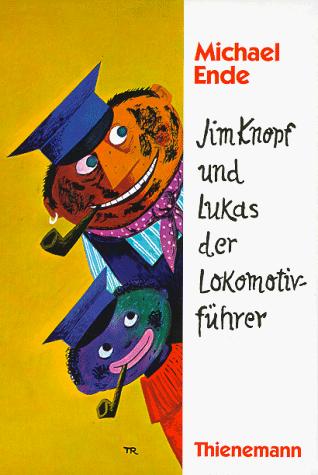

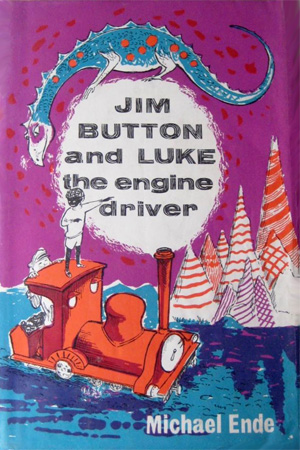

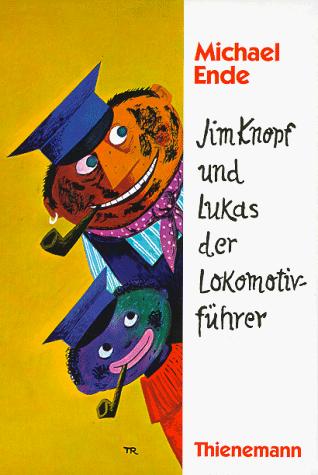

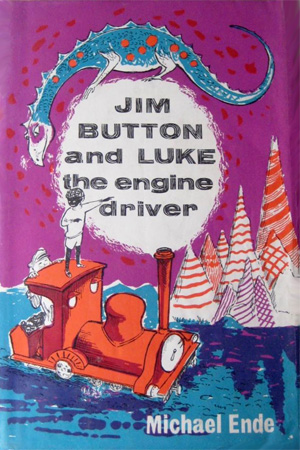

Michael Ende, who will turn 34 in two weeks, burst onto the scene three years ago with his novel Jim Knopf und Lukas der Lokomotivführer (Jim Knopf and Lukas the Train Engine Driver) followed last year by the sequel Jim Knopf und die Wilde 13 (Jim Knopf and the Wild 13). The first book has just come out in English as Jim Button and Luke the Train Engine Driver. I hope the sequel will follow soon.

The book opens in Lummerland (Morrowland in English), a small island kingdom with two mountains in the middle of the ocean. Lummerland is ruled by King Alfons, the Quarter-to-Twelfth, and has only three inhabitants, Herr Ärmel (Mr. Sleeve), a bowler-hatted gentleman whose profession is being a loyal subject, Frau Waas (Mrs. Whaat) who runs the general store, and Lukas who drives the steam locomotive Emma around Lummerland.

This balance is upset when the mail boat delivers a parcel with a barely legible address and the number 13 as the sender. The inhabitants of Lummerland decide to open the parcel, hoping to find a clue about the recipient inside. Instead, they find a black baby boy. The new arrival, christened Jim Knopf (Jim Button) is quickly accepted. Frau Waas adopts Jim, Herr Ärmel becomes his teacher and Lukas makes him his apprentice, train engine driver being a dream job for many German children.

Lummerland may seem absurd to adult readers, but it recalls the vanished world of pre-WWI Germany with its micro-states, complete with pompous rulers, where every small town had its own post office and train station. Lummerland also seems to owe more than a little to the 1958 painting Die Angst der Berge (The Fear of the Mountains) by Michael Ende's father, surrealist painter Edgar Ende. And indeed, Ende has confirmed that the painting was one of the inspirations for the story.

The fact that Jim Knopf is black may surprise many readers. There have always been black Germans, even during the Third Reich. And after World War II, their number grew as romance blossomed between black American GIs and German women and resulted in mixed race children. About five thousand so-called "occupation babies" were born in West Germany since 1945. They were subject to discrimination, both from the US Army, which discourages fraternisation, and from West German society, where the racism of the Nazi regime still festers. Some mixed race couples married and went to the US. But in many cases, the fathers were sent off to fight in Korea, Vietnam or elsewhere, leaving the mothers alone with their children. Many women were pressured to give their children up for adoption. Some of the children were adopted by black American families, others were sent to Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands.

The plight of mixed race children has been tackled before, e.g. in the 1952 movie Toxi about an abandoned little girl who is reunited with her American father. Nonetheless, Michael Ende's choice to make Jim Knopf black is remarkable, because his situation mirrors that of many mixed race German children. His biological parents are nowhere in sight; Jim is an orphan found in a box. However, unlike his real life counterparts, Jim is accepted by the people of Lummerland and his race is never an issue. He is one of them from the moment he arrives.

Trouble is brewing in Lummerland, however, because the small island is becoming overcrowded. King Alfons decrees that one of Lummerland's inhabitants has to leave. The unlucky inhabitant chosen is – no, not Jim – but Emma, Lukas' beloved locomotive. With Emma banished, Lukas decides to leave as well. Jim tags along, because he doesn't want to leave either Lukas or Emma. Lukas and Jim set out to sea aboard Emma, who is surprisingly seagoing for a locomotive.

Eventually, Jim, Lukas and Emma reach China, where they befriend Ping Pong, grandson of the Emperor's personal chef. Ping Pong tells Jim and Lukas that the Emperor is grieving because his daughter Princess Li Si has been kidnapped and is held prisoner in the dragon city of Kummerland (Sorrowland). Of course, Jim and Lukas immediately offer to rescue the princess.

But in order to see the Emperor, they first have to brave the labyrinthine Imperial bureaucracy, which is a parody of bureaucracies everywhere. Jim and Lukas also incur the wrath of prime minister Pi Pa Po, who is about to have them executed. Luckily, Ping Pong fetches the Emperor who saves Jim and Lukas, fires the villainous Pi Pa Po and makes Ping Pong prime minister instead.

Ende's China feels as fallen out of time as Lummerland. It's a land of bonzes and emperors, pigtail braids and rijstafeln (actually a Dutch Indonesian dish) that has more in common with Franz Lehar's operetta The Land of Smiles than with Chairman Mao's People's Republic of China. However, while Lummerland feels nostalgic, the orientalist clichés of Ende's China are problematic. A fictional country would have been a better choice.

Jim and Lukas learn that Princess Li Si called for help via a message in a bottle, which includes the address where she is being held prisoner, Old Street 133 in Kummerland. Jim recognises the address, because the same address was written on the parcel which brought him to Lummerland. Maybe rescuing the princess can also shed some light on Jim's origin.

Our heroes travel through fantastic landscapes, brave untold dangers and eventually, reach the Land of the Thousand Volcanoes. Here, they make another friend, half-dragon Nepomuk, who knows the way to Kummerland but cannot travel there himself because only pure-blooded dragons are allowed to enter Kummerland. Nepomuk, however, is half dragon and half hippopotamus. Adult readers will see parallels between the dragons' obsession with racial purity and Nazi race theory. And indeed, the Ende family was at odds with the Nazi regime, which branded the paintings of Michael's father Edgar Ende as degenerate art.

Jim and Lukas enter Kummerland by disguising Emma as a dragon. They locate Old Street 133 and find a school, where several children, including Li Si, are chained to desks, with the dragon Frau Mahlzahn (Mrs. Grindtooth), whose idea of pedagogics is barking orders at her pupils, as their teacher. Author Michael Ende is a supporter of Waldorf education and has said that Frau Mahlzahn's school was inspired by his experiences with the Nazi education system.

Our heroes overpower Frau Mahlzahn and free the children. Li Si explains that the children have been kidnapped by a pirate gang called the Wild 13 and sold to Frau Mahlzahn. The same fate was intended for Jim, only that he was mailed to Lummerland instead.

Jim, Lukas, Emma and Li Si return to China with a reformed Frau Mahlzahn in tow. The Emperor promises Li Si's hand to Jim, though both of them are a little young to get married. Frau Mahlzahn announces that she will hibernate to become a golden dragon of wisdom. Frau Mahlzahn also comes up with a solution to Lummerland's space problems, for she knows the location of a floating island that would make a good extension for Lummerland.

The novel ends with Lukas, Jim. Li Si and Emma returning home, the floating island in tow, which is dubbed Neu-Lummerland. And not a moment too soon, for Lukas reveals that Emma is pregnant. I don't even want to imagine the mechanics of this, but luckily the young target audience is more accepting. Emma gives birth to a baby locomotive named Molly and Jim now has a locomotive of his own.

Jim Knopf's adventures continue!

The adventures of Jim, Lukas and their friends continue in Jim Knopf und die Wilde 13 (Jim Knopf and the Wild 13). As the title indicates, the second book focuses on Frau Mahlzahn's partners in crime, the pirate gang known as the Wild 13, who remain unseen in the first book. Though Wild 13 is a misnomer, for there are only twelve pirates, all identical brothers, but they counted the leader twice. What is more, each pirate can only write a single letter of the alphabet, which explains their spelling problems and why their mailings keep ending up at the wrong address.

When the Wild 13 kidnap Molly, Jim, Lukas, Emma and stowaway Li Si go after them. Everybody except Jim is taken prisoner. Jim uses the fact that the pirates aren't particularly bright against them and gets them to accept him as their leader. One thing I like about the Jim Knopf books is that the villains are reformed rather than vanquished. This solution might seem a little too neat for adults, but learning that enemies can become friends is an important lesson for kids.

Jim also learns the truth about his origin. He is Prince Myrrhen of the sunken land of Jamballa who was kidnapped and sold to Frau Mahlzahn, but ended up in Lummerland instead. And because a prince needs a kingdom, Frau Mahlzahn and the Wild 13 help Jim raise Jamballa from the ocean (after sinking it in the first place). Jim takes the throne, marries Li Si and everybody lives happily ever after.

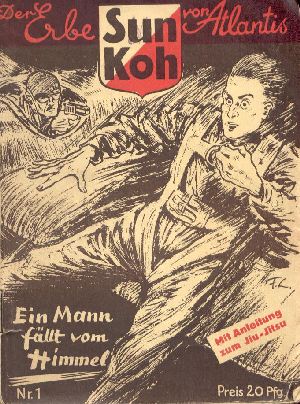

The parallels between Jamballa and Atlantis are obvious. Ende subverts the Nazi take on the Atlantis myth here, according to which Atlantis is the original homeland of the Aryan race. One example is the 1930s Heftroman series Sun Koh – Heir of Atlantis by Paul Alfred Müller a.k.a. Freder van Holk, which has several parallels to Jim Knopf's story. Like Sun Koh, Jim is the prince of a sunken kingdom, which he raises from the ocean. Only that in Ende's version, the original inhabitants of Atlantis – ahem, Jamballa – were not Über-Aryans, but descendants of the Biblical Wise Man Caspar and therefore black.

Michael Ende does his best to create a diverse and inclusive world, where yesterday's enemies can become today's friends and little black boys can become both kings and train engine drivers and marry the princess, too. Li Si is not just a damsel in distress, but a smart and resourceful person in her own right. Future generations may find issues with the books, but for now Michael Ende has created a remarkably progressive fantasy series.

A hard but certain sell

The reaction to the books was mixed. It took Michael Ende three years to find a publisher. Furthermore, contemporary German literature is focussed on realism and fantasy novels are dismissed as escapism. This is unfair, for the Jim Knopf novels are so much more. The jury of the Deutscher Jugendbuchpreis agreed and named Jim Knopf and Lukas the Train Engine Driver the best children's book of 1960. The popularity of the Jim Knopf books inspired the Augsburger Puppenkiste marionette theatre to adapt them into puppet plays, which were also filmed for television. And children everywhere love the adventures of Jim, Lukas and friends.

Jim's story came to a neat ending in Jim Knopf and the Wild 13, but will adventurers like Jim and Lukas really retire or does Michael Ende have yet more stories up his sleeve? But whether Ende revisits Lummerland or not, he is a great emerging voice of German fantasy and I for one can't wait to see what he will do next.

A lovely story about a boy, his friends and his locomotive. Four and a half stars.

![[December 31, 1963] A not unpleasant ordeal (<i>Ordeal in Otherwhere</i> by Andre Norton)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631231Cover_Ordeal_in_Otherwhere-419x372.jpg)

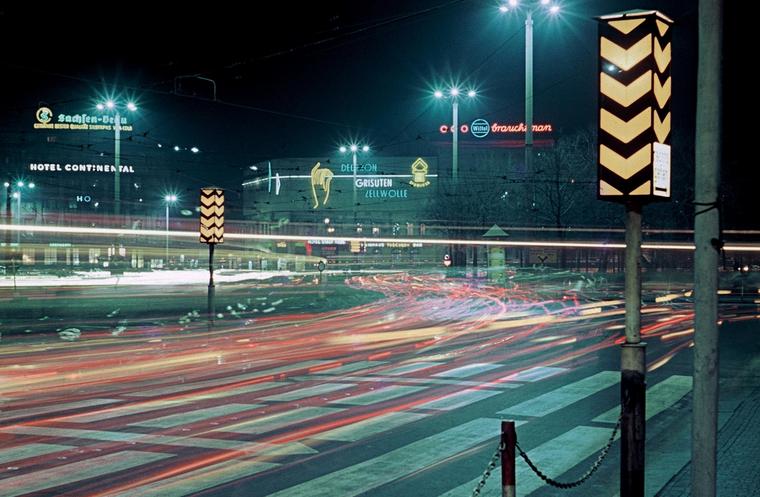

![[November 24, 1963] Mourning on two continents](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631123Flowers_Schoeneberger_Rathaus-672x372.jpg)

![[Oct. 30, 1963] <i>Jim Knopf and Lukas the Train Engine Driver</i> by Michael Ende: A Classic in the Making](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631030Cover_Jim_Knopf_English.jpg)

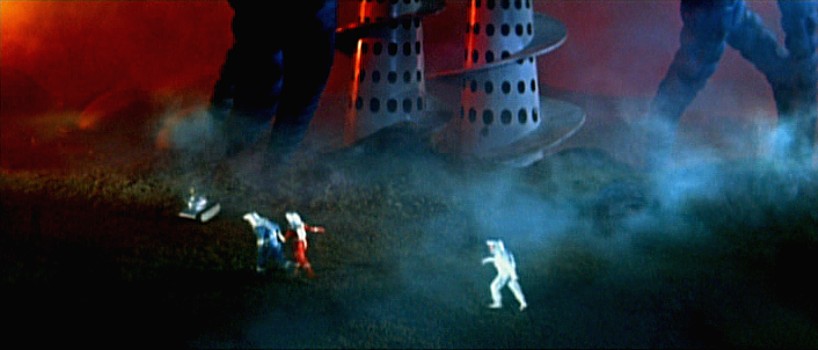

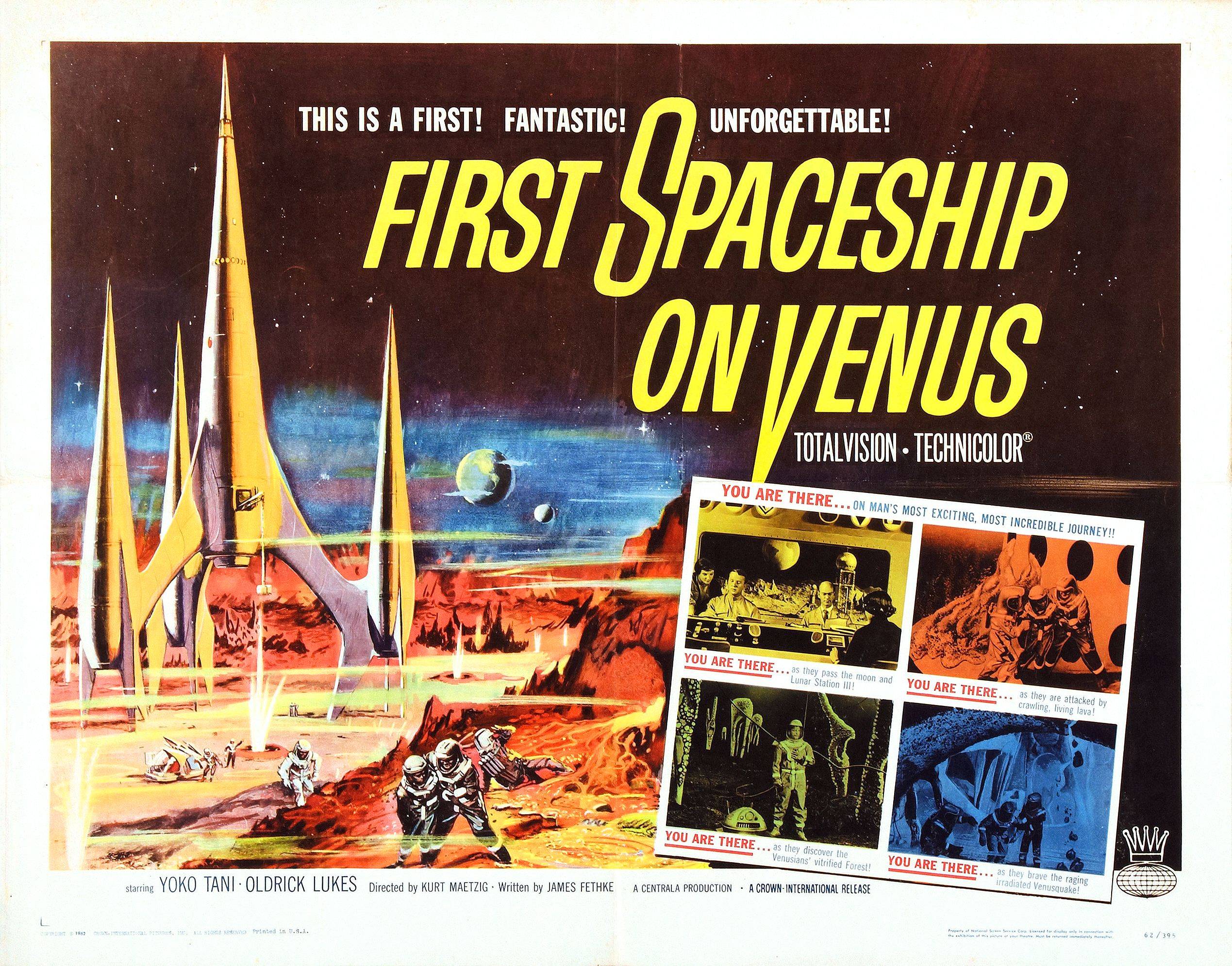

![[September 15, 1963] <i>The Silent Star</i>: A cinematic extravaganza from beyond the Iron Curtain](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630915German_poster-672x372.jpg)