Thirty years ago, Arkham House was founded as a small but luxurious publisher, with the intention of preserving the works of H. P. Lovecraft via hardcover editions that would last through the decades. Lovecraft died in 1937, before the vast majority of his work got to be published in book form, and indeed some of his finished work, such as The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, would not see publication at all until after his death. Arkham House's ambitions soon grew, and it's still going strong, even if works by the old pulp writers are now seeing affordable paperback releases.

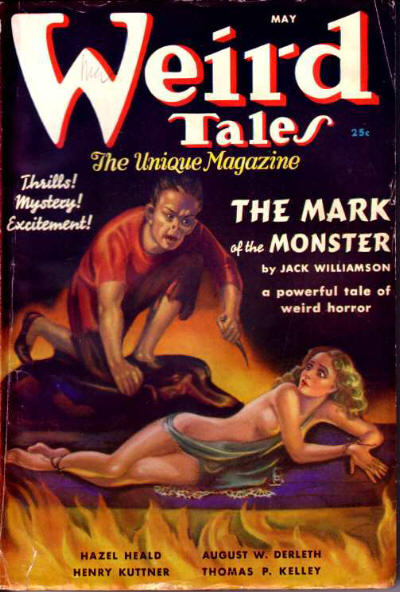

Cover art by Lee Brown Coye

Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos is a bulky new anthology, here to celebrate four decades of weird fiction in connection with Lovecraft; and while it has a limited run of some 4,000 copies, you should consider yourself one of the lucky few if you can acquire it. Because of its length, and also it combining reprints with original stories never before published, the reviews are split between me and my good colleague George Prichard, I focusing more on the reprints while he takes most of the original stories. This should be fun, and a little spooky.

The Cthulhu Mythos, by August Derleth

Derlath has been the primary chronicler of Lovecraft’s career for the past thirty years, ever since he co-founded Arkham House with Donald Wandrei all those years ago; so it only makes sense he would provide a history (as he sees it, anyway) to the so-called Cthulhu Mythos. As Derleth points out, Lovecraft never referred to the Mythos as such, but it was a name those in his circle were keen on adopting—those in the circle including Robert Bloch, Robert E. Howard, the much missed Henry Kuttner, among others. Bloch wrote “The Shambler from the Stars” when he was but a teenager, and Lovecraft wrote “The Haunter of the Dark” as a response to Bloch’s story. Both are included here, along with a distant followup from Bloch titled “The Shadow from the Steeple,” all three presented “for the first time together in chronological order.” Otherwise Derleth sought to present these stories more or less as they appeared in publication order, the Mythos thus being showcased in a mostly linear fashion.

No rating for this introductory essay.

The Call of Cthulhu, by H. P. Lovecraft

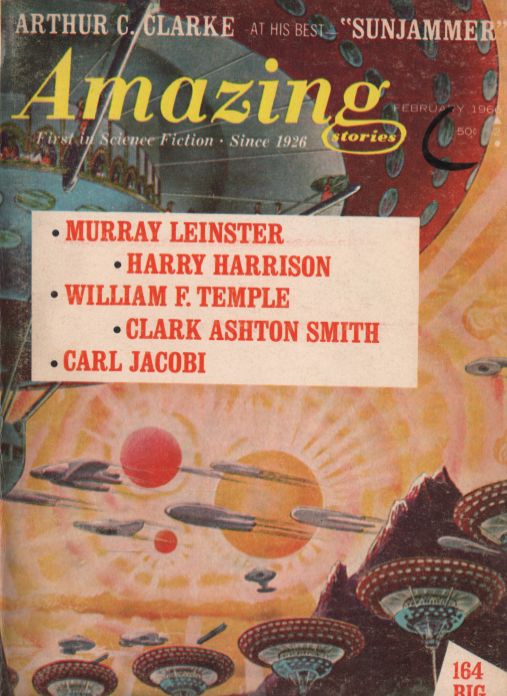

First published in the February 1928 issue of Weird Tales.

While not strictly the first Mythos story, Derleth considers “The Call of Cthulhu” to be the proper genesis of this loose series, so it goes first. I’ve read this story a few times over the years and find myself warming up to it more with each reread. It’s one of Lovecraft’s more unconventionally structured stories—what we might call a compressed novel rather than a traditional short story. An anthropologist rummages through the papers of his recently deceased uncle and uncovers, gradually, a conspiracy involving an ancient cult, a young sculptor whose fever dreams were telepathically linked to unrelated parties, a Norwegian sailor who narrowly survived an encounter with one of the “Great Old Ones,” and of course, a statuette of the many-eyed and -tentacled Cthulhu. The opening paragraph is perhaps the most iconic in all of weird horror, a perfect mission statement on Lovecraft’s part. His obvious disdain for non-European cultures can be nauseating, but it’s also hard to deny the sheer density and sense of foreboding with his writing here.

One last thing: I noticed the narrator mentioning Arthur Machen and Clark Ashton Smith by name—the latter for his poetry, as at that time (Lovecraft wrote “The Call of Cthulhu” circa 1926) Smith had yet to break through with his prose fiction. But he would, soon enough.

Four stars.

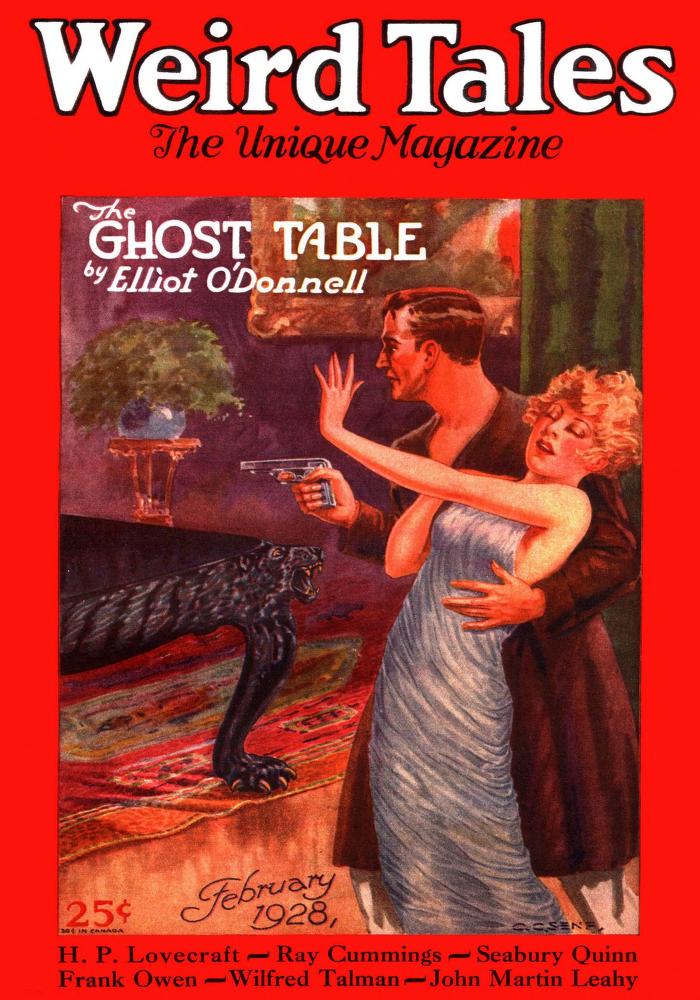

The Return of the Sorcerer, by Clark Ashton Smith

First published in the September 1931 issue of the long-forgotten Strange Tales of Mystery and Terror. I highly suggest tracking down copies, as H. W. Wesso did really striking covers for all seven issues.

Here we have the first of two Clark Ashton Smith stories, and this one is delightfully gruesome and gothic. A down-on-his-luck narrator agrees to work for the eccentric John Carnby as a typist and translator. Carnby lives in a decrepit mansion by himself, where supposedly there’s a bit of a rat problem—only the strange noises the narrator hears at night turn out to not be rats. His job is to type up many pages of manuscript, but also to translate passages from the Necronomicon, a cursed book penned by “the mad Arab” Abdul Alharred. (Readers may know, of course, that the Necronomicon is a fictitious text of Lovecraft’s invention.) Smith is often a joy to read simply for the elaborateness of his style, which seems to have its own kind of hypnotic pull; but the main draw of “The Return of the Sorcerer” is how Smith weaves together a narrative about a haunted mansion (haunted not by ghosts but rather a dark past), a man obsessed with the occult, and a creeping revenge plot. There’s also a surprising amount of gore, and while the twist is easy to anticipate, the execution of it is exquisite.

Four stars.

Ubbo-Sathla, by Clark Ashton Smith

First published in the July 1933 issue of Weird Tales.

Paul Tregardis is a normal Londoner, except for his fascination with antiquity and the occult—a fascination that may well spell his doom. A chance encounter with a strange crystal in an antique shop will send Paul on a voyage the likes of which he could not have anticipated. This is a short moody piece that serves first of all to stitch together the Mythos with Smith’s own Hyperborea series. Hyperborea itself is an alternate distant past in which magic and sorcery ruled, and one sorcerer in particular, Eibon, was able to contact unspeakably ancient horrors for his own ends. Eibon himself is more spoken of than seen, although we do meet him in Smith’s “The Door to Saturn.” But The Book of Eibon, mentioned in “Ubbo-Sathla,” is perhaps Smith’s biggest contribution to the Mythos. Smith at his best can compress a mind-bending trek through time and space into just a handful of pages, and the climax here, in which our hapless protagonist travels backwards through time in a “monstrous devolution,” stands out as one of his most pyrotechnic and hallucinogenic passages.

Four stars, especially if read while on mind-altering substances.

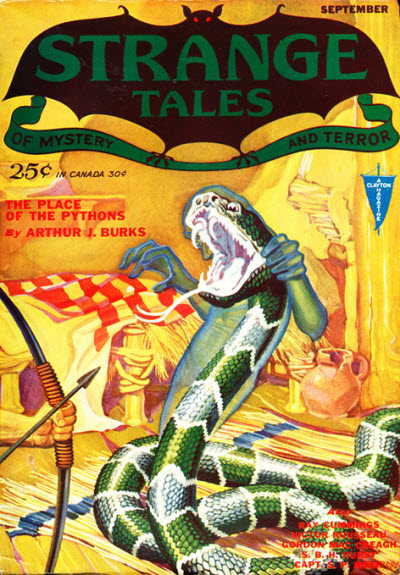

The Black Stone, by Robert E. Howard

First published in the November 1931 issue of Weird Tales.

The creator of Conan the Cimmerian also wrote a few stories which clearly took after Lovecraft, with “The Black Stone” being the best of them. An unnamed narrator ventures out to Stregoicavar, an obscure village in the mountains of Hungary, a totally unassuming place if not for an ancient black monolith that lies just outside of town. About four centuries ago the area of the village belonged to a people of mixed ancestry, “an unsavory amalgamation,” who tormented the people in the lowlands, i.e., the ancestors of those who now live in Stregoicavar. But there was a war, in which the Turks had invaded and exterminated the mixed-race people, with only some ruins and the Black Stone to show for the ordeal. What separates “The Black Stone” from most of its ilk, indeed what it does better than the vast majority of horror now being written, is its sense of location and history. I had read this story before, when it was recently reprinted in a Howard collection, and on a second reading it’s still immensely eerie and mysterious. What the narrator witnesses when he spies on the Black Stone on Midsummer Night is one of the more disturbing passages in classic weird fiction.

Basically a masterpiece. Five stars.

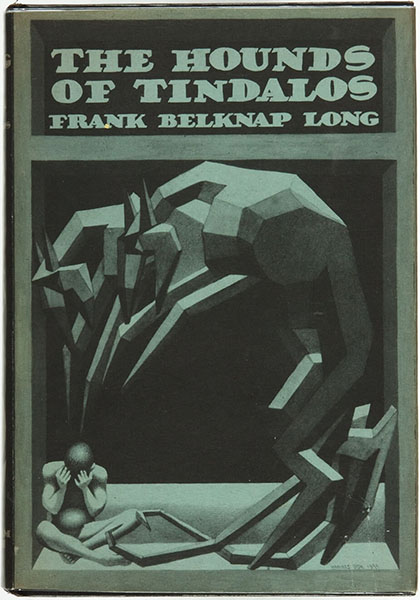

The Hounds of Tindalos, by Frank Belknap Long

First published in the March 1929 issue of Weird Tales.

This is sometimes considered the first non-Lovecraft Mythos story, although Long’s own “The Space-Eaters” predates it by a year. Lovecraft would incorporate the titular hounds in at least one later story of his, and it’s not hard to see why. This is a story concerned partly with a topic I’m sure some of us are familiar with: drugs. Frank is a normal man who happens to be friends with Chalmers, a scientist-mystic who, in concocting an experimental drug, seeks to break down the fourth dimension (time), which he hypothesizes is an illusion. Needless to say the experiment goes very badly. We never see the hounds, although the late great Hannes Bok did depict them quite memorably once upon a time. They are, in keeping with Mythos lore, amoral more than anything, “beyond good and evil as we know it.” What could be a formulaic horror yarn is much elevated by Long’s admirable attempt at combining cosmic fear with scientific rationalism, resulting in a story that bends the mind as both horror and science fiction. It may have helped inspire Lovecraft to take a more SFnal direction with later Mythos stories like “The Dreams in the Witch-House” and “The Shadow Out of Time.”

Four stars.

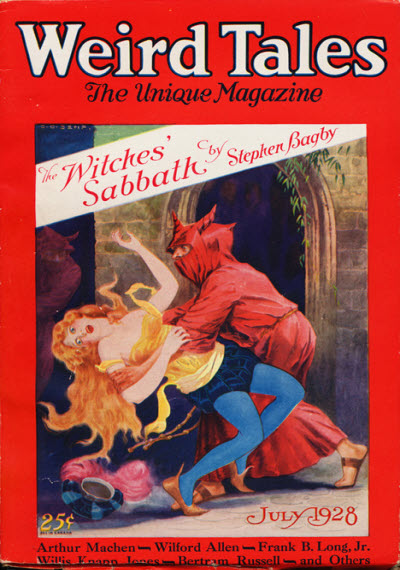

The Space-Eaters, by Frank Belknap Long

First published in the July 1928 issue of Weird Tales.

Here’s Long again, this time with a less conventional (but also less satisfying) tale of unseen horror. This verges on being more of an autobiographical commentary on Long’s friendship with Lovecraft than a fictional narrative, but Long does not take the leap that would have pushed it over the edge. If Chalmers in “The Hounds of Tindalos” was a bit of a stand-in for Lovecraft then the narrator’s friend in “The Space-Eaters” is much more so: he is even named Howard, and is also a writer of weird fiction. There’s something about a creature with tendrils lurking in the woods, which similarly to the hounds moves through extra-dimensional space (although not through angles), such that normally it goes unseen. A local drunk falls victim to the titular eaters, with a strange gaping wound in his head, before the narrator and definitely-not-Lovecraft run the risk of meeting the same fate. As a story it’s a bit of a mess, and a bit too long, not to mention that this is more obviously an early Long story; but as a glimpse into the early days of the so-called Lovecraft circle, it’s certainly worth a read.

Three stars.

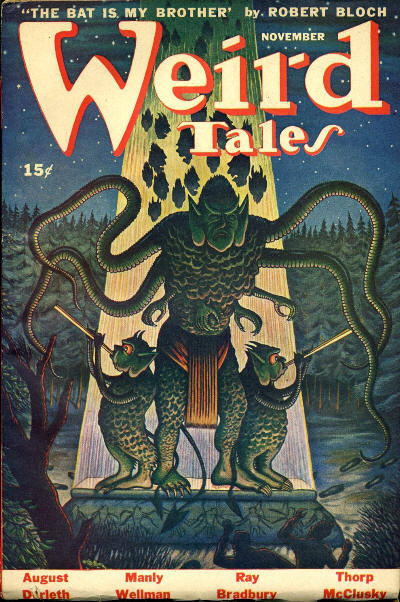

The Dweller in Darkness, by August Derleth

First published in the November 1944 issue of Weird Tales.

Apparently not content to include other people's stories, Derleth took it upon himself to include two of his own, which are both connected with the Mythos. "The Dweller in Darkness" is the slightly stronger of the two and easily the longer (bordering on a novella), but I can't say Derleth's skills as a writer have been sorely missed as of late. This one involves Rick's Lake, a shunned area in rural Wisconsin (a favorite locale for Derleth, understandably given he's from there), two educated friends trying to solve a mystery, and an enigmatic professor of the occult named Partier. There's also an unfortunate local "half-breed" named Old Peter who is deathly afraid of what may be lurking in the area, and who gets taken along for a ride—of sorts. The atmosphere is quite rich, and I suspect Derleth took some inspiration from the Loch Ness monster mystery/hoax with both the locale and the lengths the narrator and his college friend go to witness the hitherto unseen horror. Unfortunately it's overlong, and the payoff is a little too reminiscent of Lovecraft's "Cool Air," only without the tragic grotesquery of that story's ending.

A high three stars.

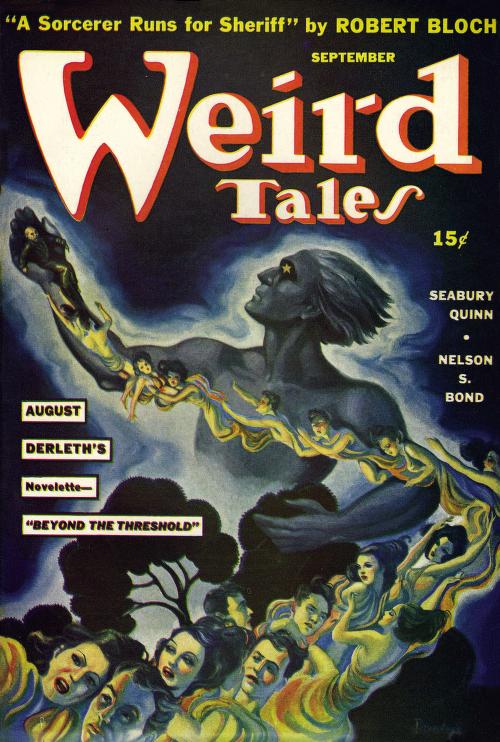

Beyond the Threshold, by August Derleth

First published in the September 1941 issue of Weird Tales.

Once again Derleth, and once again in rural Wisconsin. The narrator and his cousin visit their grandfather's mansion to study leftover papers from a deceased relative—one who had gone "beyond the threshold," perhaps ventured into another dimension. The grandfather is perhaps a little too determined to follow his leader, and the results are predictably tragic. This one starts off promisingly but then becomes a perfectly serviceably cross between Gothic and cosmic horror—a mixture I think Clark Ashton Smith pulled off with far more elegance and spectacle in "The Return of the Sorcerer." Something I didn't mention with "The Dweller in Darkness" is that both of Derleth's stories take place in a world where Arkham and Miskatonic University are real places, yes, but Lovecraft's fiction is also real, which I found to be distracting. For example the narrator will read a copy of The Outsider and Others, which Derleth himself had published. A little self-congratulatory, yes?

Barely three stars.

by George Pritchard

“The Shambler from the Stars”, by Robert Bloch

“The Haunter of the Dark”, by H.P. Lovecraft

“The Shadow from the Steeple”, by Robert Bloch

I am grouping these three stories together, as they are interlinked. As in the Derleth stories (and, later, the J. Ramsey Campbell one), Lovecraft's stories are both real, and exist in the world. Unlike my fellow reviewer, I found this added depth to the work. Perhaps it is simply due to my own experience, or that Bloch is a better author than Derleth is — both are possible. The three stories describe the accidental summoning of a creature (the titular Shambler), its aftermath, and partial defeat. Robert Blake, a Weird Fiction author from Milwaukee and a stand-in for Bloch, takes center stage for much of the first two stories, until his death at the Shambler's tentacles. From there, the narrative is taken over by William Hurley, who reaches out to Lovecraft himself to find out what happened to this "Blake" fellow!

I can think of no better tribute, from one horror writer friend to another, than dramatically killing each other off at the dastardly tendrils of a blood-soaked horror.

Four stars.

“Notebook Found In A Deserted House”, by Robert Bloch

This story, written in the form of a journal entry, suggests a sharper miniature of “The House on the Borderland”, with a strong American voice coming through. The USPS is apparently familiar with shoggoths.

Bloch’s great strength, amongst Weird Fiction authors, is his Artful Dodger-like ability to “do the voices”. Different characters sound different, speaking and thinking in distinctive ways that nevertheless seem natural to them. Too often, the characters in Weird Fiction “sound” the same, having similar cadences to whichever author is writing them, from Machen to Hodgeson. Furthermore, Bloch is willing to write characters further down the class ladder than other Weird Fiction authors. The genre may love M.R. James and the Decadents, but that mistrust for anyone who wasn’t an Oxford man of good standing has left marks that may never be worn away.

Four stars.

Hello again. I still have one more reprint, plus an original story here.

The Salem Horror, by Henry Kuttner

First published in the May 1937 issue of Weird Tales.

Kuttner died in 1958, tragically young like Robert E. Howard (Howard shot himself, and Kuttner was struck down by a heart attack at only 42), but he wrote a great deal in a short time. "The Salem Horror" is very early Kuttner, and admittedly I sense some DNA left over from his very first story, "The Graveyard Rats," what with the claustrophobic setting and the close encounters with rats.

A novelist in the midst of writer's block moves to Salem to stay in a house that belonged to a witch, many decades ago, and which has since become a place of ill repute in the already-infamous town; but the novelist is convinced he may find inspiration there, and he may be more right than he knows. Kuttner was not a poet like Lovecraft or Smith, or even Howard when he was really trying; but the pulpy vividness of his style gives this tale of dark corners and growing obsession an immediacy that elevates what is mostly a one-man show into one of gripping eeriness. Kuttner, in trying to pay the bills, could repeat himself, but "The Salem Horror" very much builds on the sort of dread introduced in "The Graveyard Rats" rather than simply rehashing it.

A light four stars.

The Haunter of the Graveyard, by J. Vernon Shea

Elmer Harrod owns the house closest to a "disused" cemetery, which nowadays mostly is visited by vagrants and young lovers. Harrod himself hosts a late-night TV show in his own home, having the right setting for such a thing—a Gothic mansion that seems out-of-place in the 20th century. He shows and commentates over trashy horror movies, some of which are based on Lovecraft's fiction. (Yes, this is another story where Lovecraft's writing exists in the world of the story, but it's used to more interesting ends here.) Immediately you can tell "The Haunter of the Graveyard" was written in the past few years partly because of the role TV (and made-for-TV movies) plays, but also it very much takes place in a world (one very much like ours) where the Mythos stories have not only been vindicated to some degree but have even inspired other works of horror. Unfortunately the ending is a letdown, and I feel like Shea could have gone farther with his premise; but putting that aside, it's a little "far out," in a good way.

A high three stars.

by George Pritchard

“Cold Print”, by J. Ramsey Campbell

Sam Strutt is a compellingly loathsome figure. A PE teacher in England, he spends his free time seeking out transgressive gay pornographic literature, and being disgusted by the grime and filth of the world around him. He enjoys his work in a particularly sadistic fashion, both on and off the clock, though this is derived from Strutt’s personality rather than his sexuality. And yet, Campbell writes so that there is something compelling about Strutt, about his dedication and knowledge to the seeking out of the books he loves. Horror readers may recognize themselves in that seeking out of the awkward, the hidden, the forbidden, no matter the cost to oneself or to others.

An understanding is sought out, and an understanding is achieved…

And now, if you'll excuse me, my thoughts on this piece:

We exist in a world after Hemingway. After Hemingway, after Steinbeck, and after Jackson.

We exist in a world where Edward Bulwer-Lytton is no longer one of the most influential authors alive, and there are greater monsters than Joris-Karl Huysmans. While hugely popular during his lifetime, Bulwer-Lytton is now best known for contributing the phrase "It was a dark and stormy night…" to Peanuts. Huysmans, meanwhile, codified not only the descriptions of sexually charged Satanic ritual in the modern day through his novel Las-bas, but the type of character now referred to as "the Lovecraft protagonist" comes from his Decadent novel Against the Grain.

It is frustrating, then, to see re-imaginings, re-writings, and reckonings of Weird Fiction through the lens of Lovecraft, as though the genre had only been composed by one hand, for good and for ill.

I would be the first to admit that Weird Fiction has always lagged behind when it comes to depictions of sexuality. Some of Arthur Machen’s stories have had elements of sex, such as in “The White People”, and “The Great God Pan”. And I confess that Lovecraft’s own “Dagon” has always set both my Jungian and Freudian tendencies abuzz. But most often, Weird Fiction has enshrined its horror in physical and mental solitude. (Putting this at Lovecraft’s feet gives M.R. James short shrift, as well as avoiding Weird Fiction’s long standing conversation with the Decadent literary movement. How strange, to have this peculiar little offshoot outlast the others! One thinks of the relation between elephants and the common hyrax.)

What makes “Cold Print” so refreshing is that it doesn't shy away from sexuality. This has been a decade of seismic shifts, one of the greatest of those being in regards to portraying sex on the page, or speaking openly about it, putting sexuality and desire forefront in SF and fantasy fiction. Some of these examples have been better than others, but it is Ramsey Campbell’s “Cold Print” which has finally allowed Weird Fiction to put its hat in the ring. Let the other fellow beware—this is a "Campbell" worth watching.

Five stars.

“The Sister City”, by Brian Lumley

A kinder, yet more engaging, version of “The Shadow Over Innsmouth”. After this, I am sure that I will not be the only one wandering the fens, hoping to encourage the Second Change!

Four stars.

“Cement Surroundings”, by Brian Lumley

Giant centipede vs. Gatling gun. Need I say more?

Four stars.

“The Deep Ones”, by James Wade

A psychic researcher arrives in San Simeon to help with dolphin research. But trouble is in the waters — a peculiar love quadrangle begins to form between the psychic researcher, the project head, the comely assistant, and their prize dolphin! All the while, a mysterious hippie group wants the research to end. But why?

This is not strictly a bad short story, but in comparison to the rest of the collection, it’s definitely the weakest. What it lacks is a full sense of focus. “The Deep Ones” is not sure if it wants to be a serious yet dreamlike story, or a parody of Ballard, Lovecraft, hippiesploitation, and Weird Fiction. When you write something like this, you need to either fish or cut bait.

Three stars.

“The Return of the Lloigor”, by Colin Wilson

A deliberate rundown of Weird Fiction’s greatest hits, eagerly gathering them into a true culmination of a “mythos”. All the density of the genre’s best, without the awkward meandering! Unfortunately, about halfway in, the author reveals that he has not bothered to update any of the story’s politics since Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. A strong beginning, and a weak end.

Three stars.

Summing up

Many Weird Fiction authors are fascinating in their own right, regardless of how well they are remembered today. William Sharpe, for all his activism in life, has dropped to the bottom of the proverbial stack; while Robert Chambers’ one slim volume has outlasted his numerous romances. I am overjoyed that I have been allowed to help welcome in a new generation of the Weird, of what is now being called the Cthulhu Mythos. With no story in the collection dropping below three stars, I highly recommend you run (or swim and crawl, slither or creep or ooze) to purchase a copy of this work. Let nobody say that August Derleth does not extend his influence as wide and deep as the King in Yellow himself!

Four stars for the whole.

![[November 18, 1969] Weird Rising (<em>Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos</em>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/691118cover-672x372.jpg)

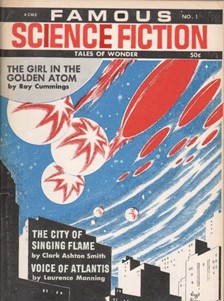

![[July 24, 1967] Not Feelin’ Groovy (<i>Famous Science Fiction</i> #1-3)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Famous-Cover-Image.jpg)

![[January 6, 1966] Have Archaic and Beat It Too (February 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/amz-0266-cover-507x372.png)