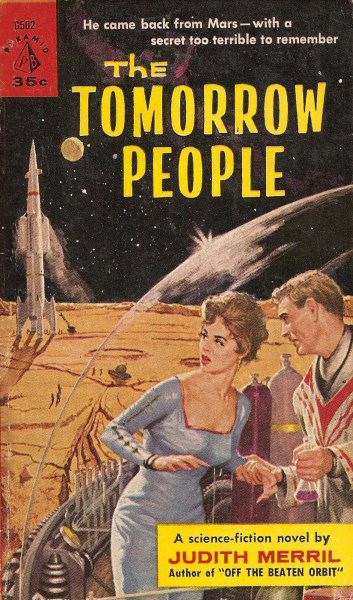

Readers of my column know of my affection for Bob Sheckley's work. A fellow landsman, he has turned out a regular stream of excellent short stories over the past decade. He's already published four collections, and they are all worth getting.

But though Sheckley gets an A for his shorter works, his novel-writing talents earn him, at best, a B-. He's written two thus far, both of them novelizations of serials. One was the tepid adventure, Timekiller. The other, The Status Civilization, was serialized in Amazing earlier this year. It just came out in book form; I'll let my readers tell me if it's been substantially changed.

The novel has a great hook: Will Barrent, age 27, wakes up from the deepest of sleeps to find he has no memories of his former existence, not even his name. Then he is informed that he is guilty of a murder he can't remember, and is sentenced, along with several hundred other mind-wiped criminals, to spend the rest of his days on the prison planet, Omega.

Like Devil's Island and Australia, this convict-ruled place of exile is a society completely apart. New arrivals start with the rank of peon, and only through a long period of virtual slavery can they rise in status. Or they can get away with murder, literally, and take the fast elevator.

Omega is a paradoxical hell world where evil is lauded, even canonized. There is law, and it is strictly enforced. And yet, status only comes when one successfully evades the law. Usually, this involves surviving the punishments for transgression–generally some kind of public gladiatorial spectacle. Of course Barrent (without much explanation) is able to survive these trials by combat and do quite well for himself.

Despite this, Barrent becomes increasingly confident that he is not a murderer, and this eventually lands him in the hands of an underground group of non-violent political criminals, whose goal is to somehow return to an Earth they know nearly nothing of. Barrent is sent on a lone mission of reconnaissance to his forgotten homeworld, which turns out to be the mirror image of Omega, or perhaps just the other side of the same coin.

The Status Civilization is an entertaining but unsatisfying read. Stylistically, it feels unpolished, even rushed. I see less of Bob Sheckley here and more of Murray Leinster on a bad day. Whole episodes of the story are glossed over, particularly some potentially exciting action bits.

Sheckley introduces us to a pair of fascinating worlds: Omega, where evil is lauded, and status is gained by murder; and Earth, where society is static, and status fixed. Neither society is stable. Both will fail at some point, though there is the suggestion that in their violent union, salvation might be found.

These are topics worthy of significant elaboration, but Sheckley gives them rather minimal treatment. Upon further reflection, I determined that he gave them the minimum treatment possible to effectively convey them. I admire his economy of words (The Status Civilization is quite a short novel), but I was left feeling hungry for more.

Which brings us to an interesting literary question: need a story be further written if it accomplishes what it was made to do? In this case, I'm going to say yes. I think Sheckley could have had a masterpiece to his name with this one if he'd just put it through the ringer one more time. It needs to either be longer or better-written.

As it is, however, The Status Civilization is worth reading. The questions it raises are compelling, even if they are incompletely answered by the author, and the writing, while workmanlike, is engaging.

3.5 stars.

[By the way, the World Science Fiction Convention is going on as we speak in Pittsburgh. I'll have a report on the con and the 1960 Hugo Awards in a few days. If you are an attendee, please feel free to add your anecdotes!]