by Jason Sacks

A miracle happened in New York City this October.

That fact might have escaped the rest of you, especially our international readers. But it began in Queens, New York this summer, and that miracle culminated in the fall.

The New York Mets won the 1969 World Series.

On the surface, it seems normal for a New York team to win the World Series. In fact, New Yorkers might feel jaded by one of the local teams winning the Series. After all, the Yankees won as recently as 1962 and played in the series only five years ago.

The winners of twenty World Series once boasted some of the most famous names in baseball history: you might have heard of legends like Babe Ruth, Joe DiMaggio, Lou Gehrig, Yogi Berra, Mickey Mantle. But it wasn’t the Yankees who won the Fall Classic in ’69. No, the ’69 Yankees finished in 5th place with an 80-81 record—merely mediocre—and a shocking 28.5 games behind the first place Baltimore Orioles (more about the Orioles shortly).

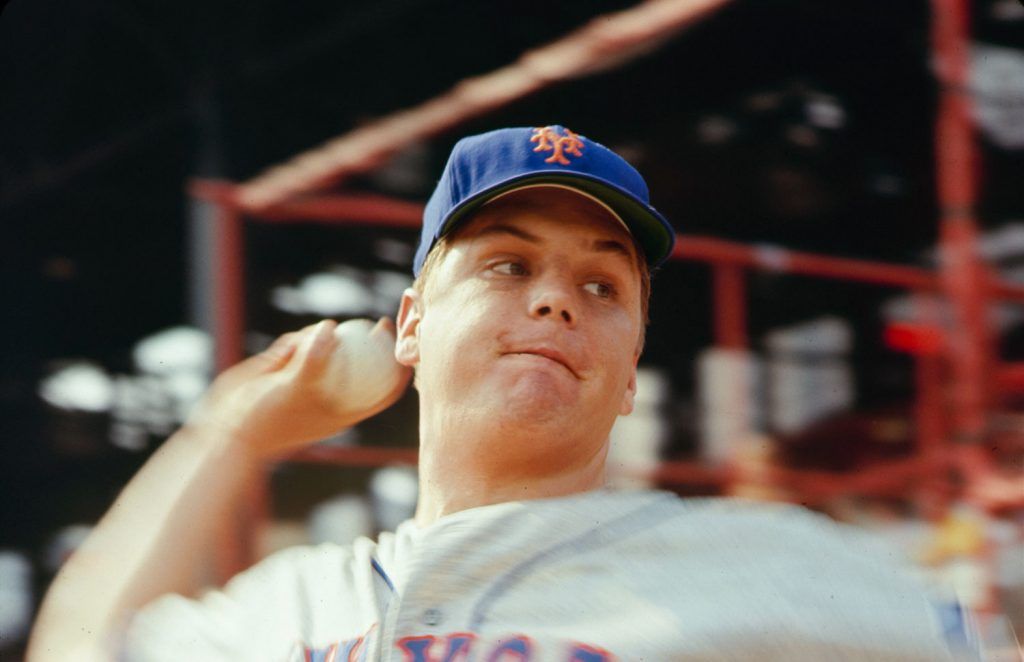

No, the champions of the 1969 World Series boasted players you’ve probably never heard of before the Series began. Who but the most avid baseball fan knew of Cleon Jones, Ron Swoboda, Timmie Agee, Gary Gentry, or Nolan Ryan?

The worlds’ champs are the New York Mets, who once entered the league as the most misbegotten of all teams. In their first year, the ’62 Mets lost more games than any other team in this century and were the laughingstock of the league (and much beloved by sophisticated New Yorkers for their ineptitude after decades of dull but excellent Yankees play). Their manager, the great Casey Stengel, once said about those original Mets, “The Mets have shown me more ways to lose than I even knew existed.”

Those original Mets were so much fun to watch because they played so badly. Their ineptitude knew no bounds. Just as one example, the ’62 Mets played “Marvelous” Marv Throneberry, at first base. He committed an astronomical 17 errors and earned one of the great baseball stories of all time. One day he hit a triple but was called out for failing to touch second base. Manager Casey Stengel went out to argue but the umpire told him, “Don’t bother arguing, Casey…he missed first base too.”

The team had a 17-game losing streak in May, lost 11 in a row in July and 13 in August. Their longest winning streak all season was 3 games. But the fans loved them. The Mets were the anti-Yankees. They were anti-corporate. They were the team of Greenwich Village rather than Madison Avenue. They were fun to watch and fun to root for: winning and losing became secondary to pure, sheer fun. This fact appealed especially to younger people looking to separate themselves from their parents’ interests.

The 1962 New York Yankees, with stars like stars like Yogi Berra, Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris and Whitey Ford, won yet another World Series. But the Yanks were serious and stolid, your father’s favorite team. As comedian Joe E. Lewis said in 1958, “Rooting for the Yankees is like rooting for U.S. Steel.” The Mets were terrible that year, but they led the League in having fun.

Things started turning around for the young team in 1967, as the Mets started building a good nucleus of great players. Long gone were the likes of Throneberry, banjo-hitting (unable to hit the long ball) Rod Kanehl, and twenty-game losers Roger Craig and Al Jackson. Instead, Tom Seaver, the Miracle Mets’ ace pitcher, arrived in 1967, won 16 games with a low-low 2.67 Earned Run Average (ERA), and promptly won Rookie of the Year. Seaver’s ERA has decreased (improved) in subsequent years, and he has just won the Cy Young Award, for best National League pitcher of ’69.

Seaver, the cornerstone of an excellent starting pitching staff which boasted the young lefty Jerry Koosman and fine righty Gary Gentry, led the Mets to an amazing 100 wins and first place in the new National League East division. The team started strong and just kept rolling all season long.

Oddly, their main rival for first place in the division was the long-suffering Chicago Cubs, led by their charismatic shortstop Ernie Banks. The Cubbies faded down the stretch, however, and the Mets emerged on top. (It’s often commented how the Cubs started really losing when a black cat ran in front of their dugout during a crucial game – a sign of how the fates hate the Cubbies, I suppose).

Meanwhile, in the American League, the mighty Baltimore Orioles emerged on top once again. The O’s are one of the most formidable teams of our time, with a roster which boasts many of baseball’s greatest superstars, household names like Brooks Robinson, Jim Palmer and the incomparable Frank Robinson. The Robinsons, Palmer and most of their compatriots were on the team which dominated the Dodgers in the ’66 World Series.

Thus the ’69 series could be compared with David’s epic battle with Goliath. The up-and-coming Mets had momentum, but they seemed overmatched in a battle with the best team of our era. Needless to say, the Orioles were prohibitive favorites.

Game One seemed to prove the prognosticators right. Orioles left fielder Don Buford belted Seaver’s second pitch over the fence for a home run, barely eluding Ron Swoboda’s leap. In the fourth inning, Orioles pitcher Mike Cuellar drove in an RBI (his turn at the plate resulted in a score), and the Orioles took the game 4-1. Cuellar was dominant on the mound, and the die seemed to be cast for the end of the Mets’ Cinderella story.

Jerry Koosman took the ball for game two for the Mets against the Orioles’ brilliant Dave McNally. The young Koosman outdueled his counterpart, as Koosman took a no-hitter into the seventh before Brooks Robinson hit a single which drove in Paul Blair (the Mets’ very first draft pick, long a starter on the Orioles). But the Mets rallied back with clutch hitting of their own and took the game 2-1. Clearly these youngsters deserved their place in the Series.

Mets outfielder Tommie Agee basically won game three on his own. Agee led off the game with a home run off Orioles ace Jim Palmer, then made two amazing outfield catches to save at least five runs on Orioles rallies. Agee’s catches are still the talk of the town, just astounding feats of athleticism.

Two other notable players contributed to the victory. Ed Kranepool, the final member of the original Mets still on the team, hit a crucial homer. Nolan Ryan, the widely praised young flamethrower out of Texas, hurled the final 21⁄3 innings. He’s been touted as an ace of the future, so I hope to see more of him in the ‘70s.

Game four had controversy before it started and more controversy as it ended. October 15, 1969, was Vietnam Moratorium Day, of course, and many New Yorkers called on Major John Lindsay to order flags flown at half-mast at Shea Stadium in Queens to honor those who died in Vietnam. Lindsay agreed, but baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn overrode Lindsay’s decision and ordered flags to fly at full staff. This caused anger on both sides.

The ending controversy happened on the field. Seaver delivered another excellent game, aided by an outstanding game-saving catch by Ron Swoboda in the ninth. The score was tied 1-1 in the 10th as the Mets hit in the bottom half of the inning. The Mets got men on first and second as pinch-hitter J.C. Martin came up to bat for Seaver. Martin laid down a sacrifice bunt, dashing down the first base line inside of the baseline. Orioles reliever Pete Richert grabbed the ball and hit Martin on the wrist with his throw. The ball went wild, the crowd went wild, and the Mets suddenly found themselves up 3-1 in the Series. After the game, many questioned whether Martin should have been called out for interference, and in fact pre-game co-host Mantle agreed.

Game five had its own controversies with two questionable calls by the umpires. In the sixth inning, Frank Robinson seemed to be hit by a Koosman pitch but the umpire ruled the pitch had hit Robinson’s hand. Therefore the pitch was a foul ball rather than a free trip to first base. Robinson subsequently struck out and a potential rally was quenched.

The opposite happened in the bottom half of the sixth when Mets left fielder Cleon Jones claimed he was hit on his foot by a Dave McNally pitch. The umpire initally said the ball bounced in the dirt, but Mets manager Gil Hodges carried the ball out to home plate and showed shoe polish on the ball. The ump awarded Jones first. Conspiracy theories abound about the ball, most claiming the polish was applied after the fact, and there is a lot of evidence which backs up that assertion.

Perhaps that weird moment presaged fate intervening for a Mets win, as in the seventh inning, light-hitting Al Weis delivered his only home run at Shea Stadium. In the eighth inning, the ubiquitous Swoboda drove in the game’s go-ahead run. By the ninth inning, the impossible looked to be happening: the Mets were three outs away from taking the Series.

As Jerry Koosman mowed down the final three outs in the ninth, Shea Stadium seemed ready to explode with pandemonium. The sounds were deafening, even on my console TV, as the third out was recorded, the New York fans flooded the field, and the most improbable event in baseball history was official.

Cinderella kept her shoe, with a bit of shoe polish scuff on it. The New York Mets, once baseball’s laughingstock, are World Series champions for 1969.

![[November 10, 1969] A Great Miracle Happened There (The Mets and the Orioles at the World Series!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/mets-field-672x372.jpg)

![[October 24, 1965] "What time is it?" (October Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/651024covers-1-672x372.jpg)