by Kaye Dee

Since Star Trek debuted in the US last year, I’ve been eagerly awaiting its appearance Down Under after reading all the fascinating episode reviews that my fellow writers have produced for the Journey.

As I’ve mentioned before , the arrival of overseas television programmes onto Australian screens can vary wildly, from a few months to several years after premiering in their home country, so I had no idea how long I might have to wait. Thankfully, this time it’s only taken about ten months for the adventures of the crew of the USS Enterprise to reach our shores, with the series premiering in Sydney on TCN-9, the flagship station of the Nine Network, on Thursday 6 July.

Who’s Watching Out for the Watchers?

Like the introduction of Doctor Who in Australia, Star Trek’s presence on our screens has had to pass the scrutiny of the Australian Film Censorship Board (AFCB), which reviews all foreign content for television broadcast in Australia – and like Doctor Who, it has not escaped unscathed. The good Doctor’s Australian premiere was delayed by the AFCB considering its early episodes not suitable for broadcast in a “children’s” timeslot. Other episodes have experienced censorship cuts of scenes considered scary for children, and the entire Dalek Masterplan story was even banned for being too terrifying! (I really must write a future article on the curious censorship of Doctor Who in Australia).

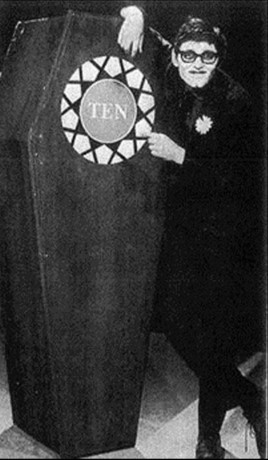

Similarly, The Man Trap , screened as the first episode in the US, has also been banned here, deemed unsuitable for the show’s 8.30pm timeslot due to its themes of vampirism! Apparently, the ACFB thinks Australian adults can’t handle a good, suspenseful horror-themed story at a decent viewing hour, even though it permits B-grade (or should that be Z-grade?) vampire and other horror movies to be screened after 10.30pm, as part of the Awful Movies show hosted by Deadly Earnest (the nom-de-screen of local television personality Ian Bannerman, seen above in character). However, that show plays on another network, so it is unlikely that we’ll see The Man Trap turn up there any time soon.

Similarly, The Man Trap , screened as the first episode in the US, has also been banned here, deemed unsuitable for the show’s 8.30pm timeslot due to its themes of vampirism! Apparently, the ACFB thinks Australian adults can’t handle a good, suspenseful horror-themed story at a decent viewing hour, even though it permits B-grade (or should that be Z-grade?) vampire and other horror movies to be screened after 10.30pm, as part of the Awful Movies show hosted by Deadly Earnest (the nom-de-screen of local television personality Ian Bannerman, seen above in character). However, that show plays on another network, so it is unlikely that we’ll see The Man Trap turn up there any time soon.

Meanwhile, the AFCB is still reviewing some of the first series episodes, but hopefully they won’t ban any more from screening in the normal Star Trek timeslot. However, the review process seems to have thrown any adherence to the US screening order out the window and the seven episodes shown so far have appeared in quite a different sequence. Commencing with The Corbomite Manoeuvre as the first episode, we’ve now seen Menagerie (parts 1 and 2), Arena, This Side of Paradise, A Taste of Armageddon and Tomorrow is Yesterday. Galileo Seven is scheduled for this coming Thursday. My favourite so far? Tomorrow is Yesterday : I'm always up for a time travel story.

This order may be at least partly based on what TCN-9 has available while the AFCB completes its reviews. But it could also be that the television station staff have been indulging in the apparently common practice (so I’m told by my friend at the Australian Broadcasting Commission) of picking episodes at random off the shelf, when no specific screening order has been defined. Still, as long as we get to see the rest of the episodes, in whatever order, I’ll be happy, even if we will only be watching them in black and white (as we’re not likely to get colour TV in Australia until the mid-1970s on current government planning).

A Sydney Exclusive For Now

Star Trek is only screening in Sydney at the moment, although it will be shown nationally later in the year on other Nine Network capital city stations. The reason for this broadcast strategy is not clear, but perhaps Nine is waiting to see how popular the series is in Australia’s largest market before scheduling it elsewhere? Even though the various Irwin Allen productions have had reasonable ratings on Australian television, science fiction is still seen as something of a gamble by Australian commercial broadcasters and Nine may not be as confident in its purchase of the series as it seems.

On the other hand, rumour has it that Mr. Kerry Packer, the son of the Nine Network’s chief shareholder, media baron Sir Frank Packer, is something of a science fiction fan – I do have it on good authority that he’s a fan of that wonderfully quirky British series The Avengers. Maybe Mr. Packer wants to enjoy Star Trek in his home market of Sydney first, before sharing it with the rest of the country?

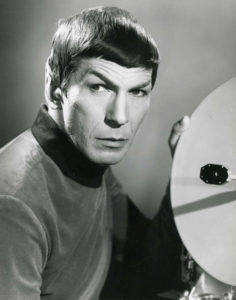

Everyone Loves Mr. Spock

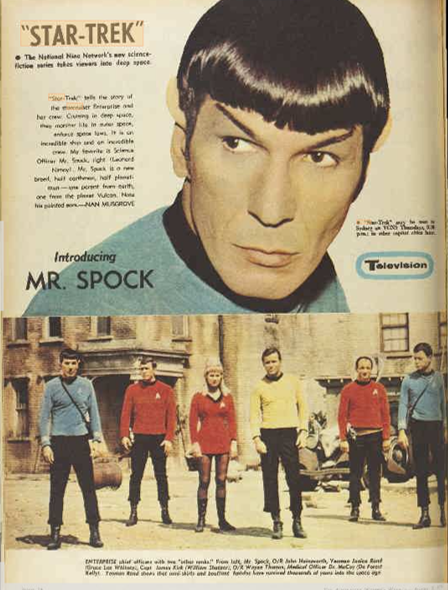

While the arrival of Star Trek hasn’t had a huge promotional campaign attached to it – unlike the debut of Mission:Impossible (see below) – Sir Frank has certainly made use of the resources of his Australian Consolidated Press magazines and newspapers to plug the series. The Australian Women’s Weekly, the country’s most popular women’s magazine, is rather conservative and not exactly known for embracing “out there” interests like science fiction. Yet its television critic, Nan Musgrove, gave Star Trek a very positive review in her column (and it does feel like a genuinely positive review, not just a promotion for a Packer interest).

A full page colour spread about Star Trek (above) has recently appeared in the 2 August issue and a further article about Mr. Nimoy’s Emmy nomination in the 9 August issue. Articles about Star Trek have also appeared in the Packer-owned TV Week magazine and Daily Telegraph newspaper.

The television critics of other newspapers and television guides have also generally reviewed the series favourably, although one did dismiss it rather scathingly (but then, I think he dislikes science fiction as a matter of principle!) Mr. Spock certainly stands out as the most intriguing and popular character to the reviewers, and to letter writers to the newspapers and magazines. Several have also commented very favourably on the multi-national nature of the Enterprise crew and the lack of racial prejudice in the series – these latter comments undoubtedly influenced by the racial unrest we’ve seen in the US in recent times.

The television critics of other newspapers and television guides have also generally reviewed the series favourably, although one did dismiss it rather scathingly (but then, I think he dislikes science fiction as a matter of principle!) Mr. Spock certainly stands out as the most intriguing and popular character to the reviewers, and to letter writers to the newspapers and magazines. Several have also commented very favourably on the multi-national nature of the Enterprise crew and the lack of racial prejudice in the series – these latter comments undoubtedly influenced by the racial unrest we’ve seen in the US in recent times.

Who's Watching?

I’ve not been able to obtain any ratings figures yet for these early Star Trek episodes, so it’s hard to really judge the show’s popularity with the viewing audience. But if what I’m hearing at the university is anything to go by, and what my sister and her husband tell me they are hearing at the hairdresser and at work, people who would not consider themselves science fiction fans (or even interested in science fiction) are watching Star Trek and enjoying it.

And it’s not just the adults that are watching Star Trek, either. My niece Vickie, who recently turned 10, asked to be allowed to stay up and watch Star Trek for her birthday (as her normal bedtime is 8.30pm). Her first episode was Arena – and she was so taken by it that she refused to go to bed at the usual time the following week, insisting that now she is a "big girl", she's old enough to stay up an extra hour one night a week! Well, how could we refuse a budding fan? So now she joins her parents and I in our new Thursday night routine of watching Hunter at 7.30, followed by Star Trek at 8.30pm.

Spies are All the Rage

Hunter, which precedes Star Trek (and commenced on the same evening that Star Trek premiered), is a new Australian-made spy drama from the Crawford Productions stable. Better known for its radio dramas and police show Homicide, Crawfords has decided to cash in on the current popularity of the espionage genre by producing a very slick, American-style spy drama based around the exploits of John Hunter, a Bond-like intelligence agent for an Australian security organisation, COSMIC (Commonwealth Office of Security & Military Intelligence Co-ordination).

Being on the Nine Network, Hunter has also been heavily promoted in the Packer-owned press, but nothing like the way in which the 0-10 Network has promoted the debut of its prize overseas spy-drama purchase, Mission: Impossible. Ahead of that show’s first screening at the end of June, TEN-10 in Sydney flew 50 journalists and celebrities down to Canberra on a specially chartered flight. The station’s guests were treated to an in-flight meal of champagne, fillet mignon and “super spy cocktails” (served by silver-mini-skirted hostesses), before enjoying an exclusive preview of the first episode, screened at the museum within the Royal Australian Mint! The 0-10 network must be expecting great things from Mission: Impossible, to spend so lavishly on its promotion.

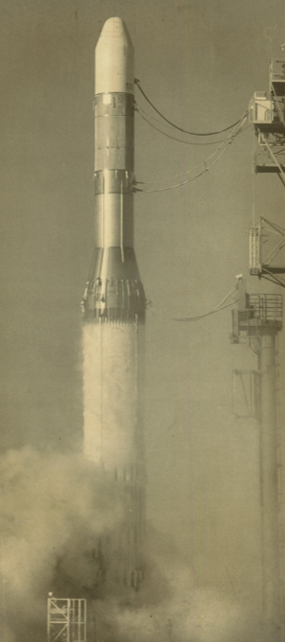

Crawfords has preferred to spend its Hunter budget, not on promotion, but on extensive location filming. This has included segments of its first six-part story, The Tolhurst File, being shot on location at the Woomera Rocket Range. Hunter is the first commercial television programme to receive permission to film at Woomera, and it’s rumoured that Hector Crawford himself made use of his high-level political connections to obtain the clearances – because right now Woomera is a very busy place indeed!

Crawfords has preferred to spend its Hunter budget, not on promotion, but on extensive location filming. This has included segments of its first six-part story, The Tolhurst File, being shot on location at the Woomera Rocket Range. Hunter is the first commercial television programme to receive permission to film at Woomera, and it’s rumoured that Hector Crawford himself made use of his high-level political connections to obtain the clearances – because right now Woomera is a very busy place indeed!

ELDO Launches at Woomera

Of course, I wouldn't let a piece on science fiction go by without a bit on actual science as well–and there is plenty to report.

It’s been over twelve months since I wrote an update on the activities of the ELDO programme. After the Europa F-4 launch was un-necessarily terminated by the Range Safety Officer in May last year, a replacement flight to test the all-up configuration of the three-stage vehicle had to be arranged. This took place on 15 November 1966, with an active Blue Streak first stage and inert dummies of the French second stage and West German third stage. The rocket’s dummy test satellite also carried instrumentation to measure the conditions that a real satellite would experience during launch.

Fortunately, this test flight was a complete success, reaching a height of over 60 miles. The dummy upper stages separated successfully from the active first stage, with all the vehicle’s components falling, as planned, into the upper region of the Simpson Desert, south-east of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory.

Not so successful, however, was the flight of Europa F-6, launched just a couple of weeks ago on 4 August. This mission was intended to be the first trial flight with active first and second stages (the third stage and satellite still being dummies). Initially planned for 11 July, the flight experienced 10 aborts and launch delays over more than two weeks due to systems problems and weather.

Not so successful, however, was the flight of Europa F-6, launched just a couple of weeks ago on 4 August. This mission was intended to be the first trial flight with active first and second stages (the third stage and satellite still being dummies). Initially planned for 11 July, the flight experienced 10 aborts and launch delays over more than two weeks due to systems problems and weather.

When the mission finally launched, while the first stage once again performed as planned, the French second stage failed to ignite. The cause of this failure is not yet known, but as many components of the French Coralie stage were reaching the end of their operational life due to the launch delays, investigations of the failure are focussed on this aspect. A reflight, already dubbed F6/2 is being scheduled for later this year, possibly November.

An "Australian" Astronaut

And Australia now has its "own" astronaut, in the person of Dr Phillip K Chapman, just this month selected as part of NASA's second group of 11 scientist-astronauts. Although Chapman, who is now an American citizen (as he had to be, in order to be eligible for the astronaut programme), will not fly as an astronaut wearing an Australian flag on his shoulder, we are all excited that he will probably participate in the Apollo Applications Program, which is planned to follow-on from the initial Apollo lunar landing program: maybe he will even get to walk on the Moon as the Apollo programme expands?

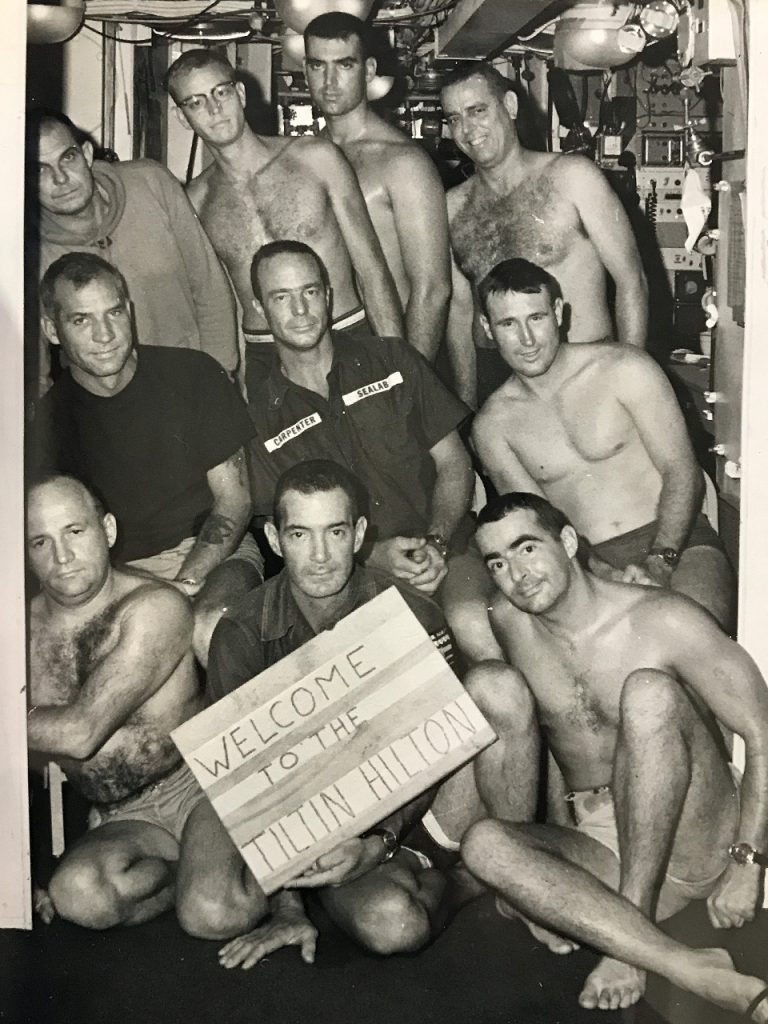

Originally from Melbourne, Chapman (seen here in the back row, extreme right) is one of the first two naturalised US citizens to be selected as an astronaut. A physicist and engineer, specialising in instrumentation, Chapman studied at the University of Sydney and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), from which he obtained a degree in aeronautics and astronautics.

Prior to his astronaut selection, Chapman's career has included studying aurorae in Antarctica, as part of the Australian expedition there during the International Geophysical Year. He also worked on aviation electronics in Canada before joining MIT as a staff physicist in 1961. Prior to his selection as an astronaut, Chapman has most recently been employed in MIT’s Experimental Astronomy Laboratory, where he worked on several satellites. I hope I'll have the opportuntiy to meet Dr Chapman some time soon, and I look forward to reporting on his future astronaut career.

And while I wait for a real life Australian astronaut to make his first flight, I can at last enjoy the adventures of the crew of the USS Enterprise for myself – and hope that one day they'll add an Australian to its crew as well!

![[August 22, 1967] Boldly Going Down Under (Star Trek, Spies and space in Australia)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/AWW-ST-448x372.png)

![[October 14, 1965] Taking a Deep Dive (the SEALAB project)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/SEALAB_II-672x372.jpg)