by Gwyn Conaway

The tragic assassination of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. in April left America reeling. Images of his final march through the streets of Memphis have been presented everywhere, his apparition and his voice still echoing through American society now, and surely for generations to come.

This, of course, includes his movement’s fashion.

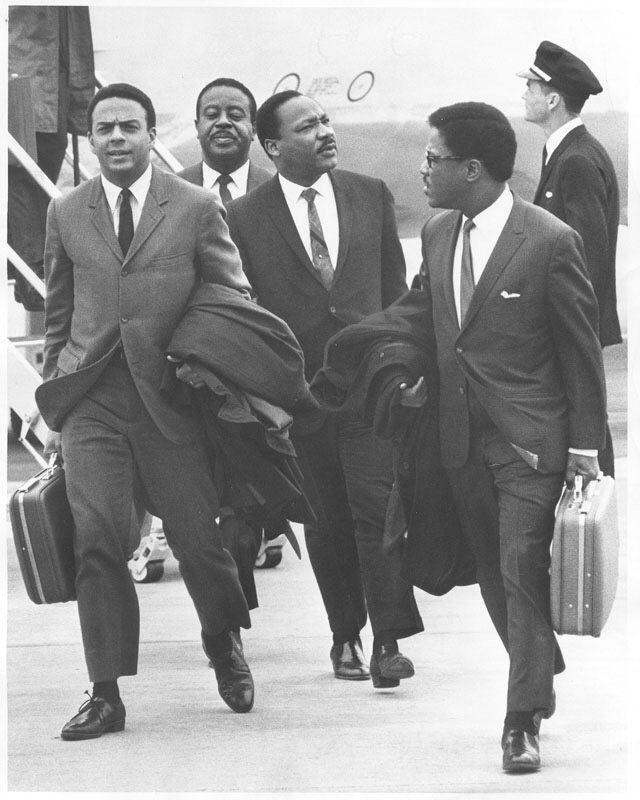

King upon his arrival in Memphis in March of 1968.

When you see photographs of King standing behind a microphone, or especially linked arm-in-arm with his collaborators, you might see nothing special. Three-buttoned suits in grey, black, brown, and navy. Pressed white dress shirts dressed with narrow silk ties and tie pins. Freshly brushed fedoras and homburgs. To many of us, this fashion is commonplace in America. This is the uniform of company men and Hollywood.

Which is exactly the point.

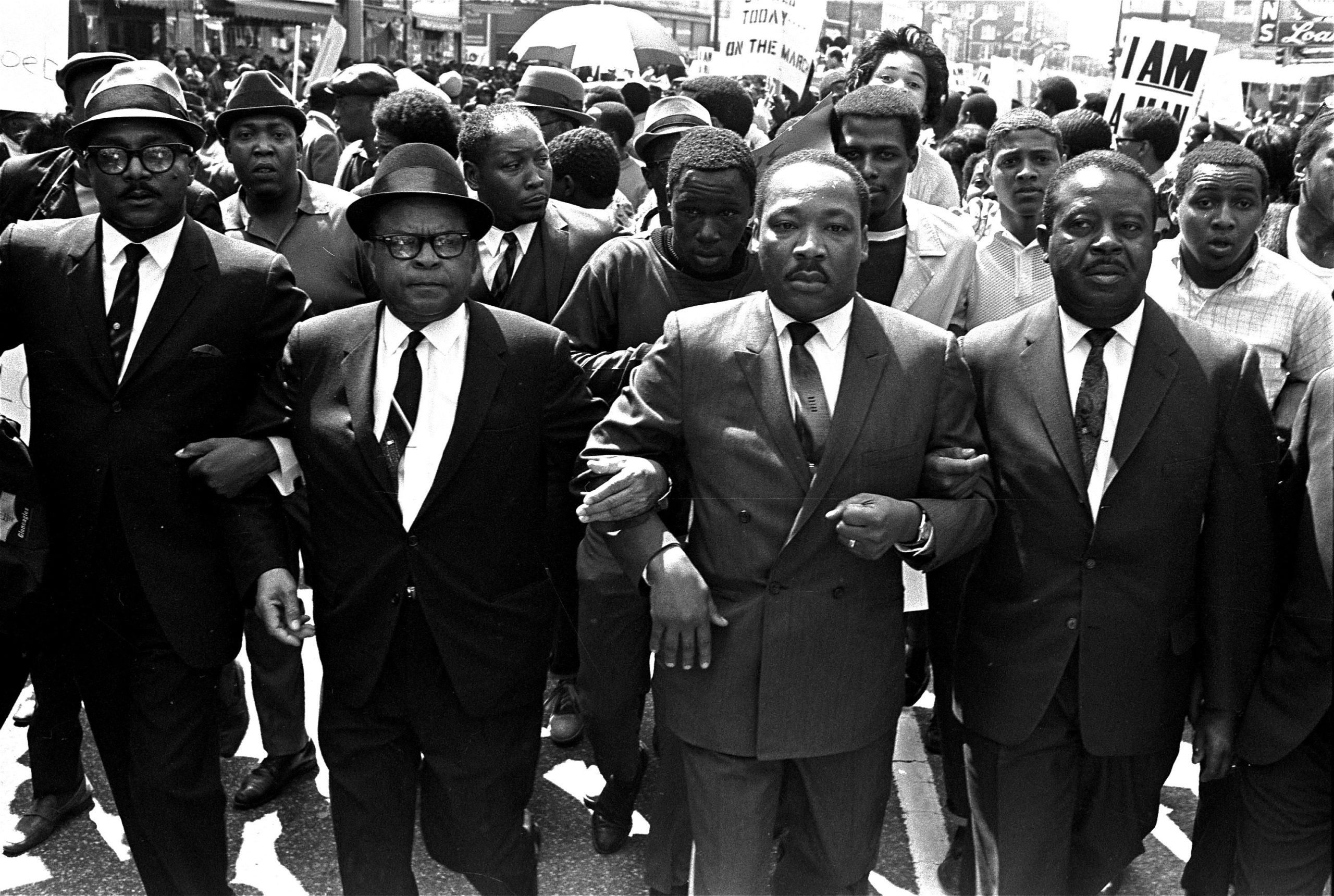

King flanked by Reverend Ralph Abernathy (right) and Bishop Juian Smith (left) in his last march in Memphis in March.

Let me interrupt myself here to say, if you haven’t perused my recent critique of Vogue and its use of women as decor for an escape from the instability of Western life, I humbly urge you to read it as a prelude to the topic of neighborly resistance I will introduce now. For in all things, fashion and beauty have purpose. In the case of Vogue in my last article, propriety is used as a tool to control the expectations of women, while here, we will see propriety used as a tool of protest.

In resistance fashion, there are two prevailing trends that exacerbate the divisions of society and define the identities and ideals of those pursuing a better world: one of negotiation, and one of force. Force is easy to recognize, often taking on militaristic elements of dress, such as the Black Panthers with their berets and leather jackets, or constructing a mystique of terror, such as the Ku Klux Klan with their pointed hoods. Negotiation, however, is difficult to separate from polite society. The message is, “I am your wife, your friend, your colleague. I am just like you.”

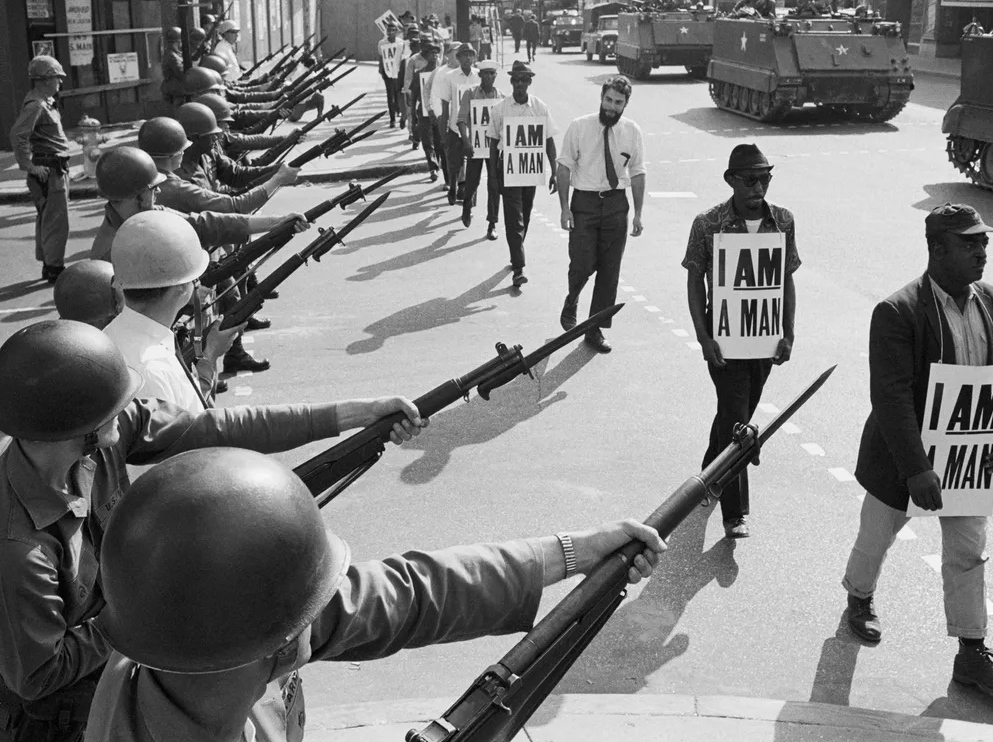

This approach makes the militaristic response to King’s peaceful protests all the more jarring. Black men and women dressed for church, walking the streets peacefully are met with primarily white servicemen and police officers with rifles, helmets, and combat boots. Rather than a potentially dangerous movement, cameras capture the dignity of Black America as it meets a terrified government at the end of a rifle barrel.

Black men and allies protest peacefully in Memphis this April in clean-cut suits, dress shoes, and ties as if attending a job interview for equal rights while the National Guard's response appears alarmist with guns raised and tanks rolling down the streets.

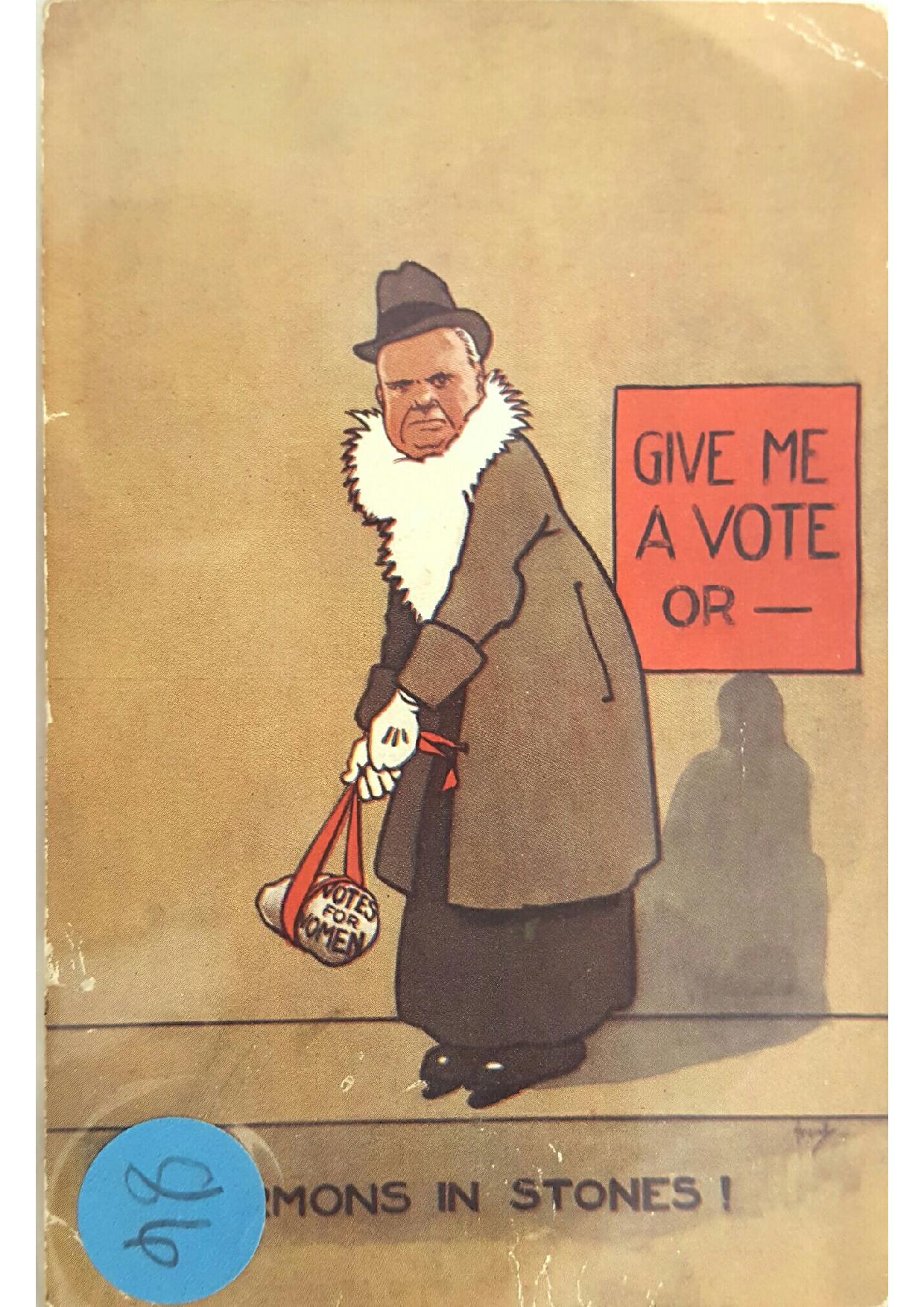

This isn’t the only time in history that we’ve seen this subtle but effective tactic in the pursuit of change. The suffrage movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries also faced threat of violence and harsh criticism. Women across the Western world were caricatured by cartoonists, politicians, and journalists as brutish and ugly for their pursuit of the right to vote. Perhaps most insidious of the stereotypes was the thought that they were uncaring and selfish mothers, unfit to raise children. Suffragists fought back against these insulting depictions through hunger strikes, riots, diplomacy, literature… and by how they dressed. By the turn of the century, the movement realized they had a public relations problem.

Thus began the image of the beautiful, patriotic, charismatic “suffragette,” a term that had previously been used to belittle the movement.

A postcard entitled "Sermon of Stones!" in which a suffragist from the turn of the century is depicted as mannish, violent, and improper.

Walt Disney's 1964 production of Mary Poppins depicts suffragettes in the late 1910s, at which point they won the battle for voting rights in America (1920) and the United Kingdom (1918). The song "Sister Suffragette" was performed by Glynis Johns as Winifred Banks, Hermione Baddeley, and Reta Shaw.

Though critics of King’s tactics within the Black community claim he’s accepting standards of white American culture rather than lifting up their own, the truth is more complex. Our identities are literally worn on our sleeves, and while the Black Panther Party may be the most recognizable civil rights group, the image of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference is just as powerful. Whether bombastic and rebellious or gentle and assimilated, fashion proves to be a powerful tool for identity, politics, and change.

I look forward to meeting my new neighbors, sooner rather than later.

![[June 24, 1968] Martin Luther King Jr. and the Fashion of Neighborly Protest](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/AP_680328013-672x372.jpg)