by Gideon Marcus

Coming of Age

The second age of American human spaceflight has begun. Until this month, the US' steps into space have been tentative. The longest Mercury flight lasted just one day, and at that, stretched its capabilities to the limit. The first crewed Gemini, launched in March, completed just three orbits — the same duration as Glenn and Carpenter's Mercury flights. In the last five years, the Soviets, on the other hand, hit the day-long mark in 1961 with Titov's Vostok 2 mission, and since then have launched two dual Vostok flights, a three-man Voskhod mission, and in March, conducted the first walk in space during the two-man Voskhod 2. The current "winner" of the Space Race was evident.

But on June 3, 1965, Gemini 4 launched into orbit, and everything is different now.

Dress Rehearsal for Moon Trips

Gemini is America's first real spacecraft. Unlike Mercury, which could do little more than spin on its axis and carry a human in space for 24 hours, Gemini has the ability to maneuver. It can rendezvous with other craft in orbit, change orbits to a degree, can stay in space for up to two weeks, and it seats two. Because of this last, an astronaut can be deployed for extravehicular activity. All of these capabilities are vital prerequisites for any Moon-bound craft, and the lessons learned in operating Gemini are directly applicable to Apollo, the three-seat spacecraft destined to reach Earth's celestial companion.

This fourth Gemini mission, the second to be crewed, was the first to really put the spacecraft through its paces. And boy did it ever. There's a reason the flight dominated the news before, during, and after the event.

Into the Wild Black Yonder

At around 8:00 PM Pacific Time (as all times shall be rendered; pardon my San Diego bias) on June 2, ground crews began fueling the repurposed Titan II ICBM that would carry the Gemini 4 capsule. Note that the ship did not and still does not have a name. This is a first, and I think it a rather sad state of affairs.

At 1:10 AM the following morning, Majors James McDivitt and Ed White, command pilot and co-pilot respectively, were awoken; whereupon they feasted on the "low residue" breakfast that has become traditional: steak and eggs.

By 5:20 AM, they were suited up and installed in their craft, take-off scheduled for 7 AM. But the red rocket erector would not come down, and for more than an hour, the astronauts waited. Would the flight be scrubbed?

Luckily, a reset of the structure freed things up, and at 7:40 AM, the Titan was clear, ready for launch. And launch it did at 8:16 AM, guided for the first time from the brand new Mission Control in Houston, Texas. The complex had been staffed for the previous two Gemini missions, but this was the first time control was formally transferred from Cape Com in Florida.

Once in orbit, the Gemini astronauts wasted no time. By the time the spacecraft had twice circled the Earth, astronaut White was already planning his jaunt into history. As Gemini 4 whizzed over North America, the co-pilot opened his hatch and stepped out into the vacuum of space. For a good twenty minutes, as the blue of the Earth slowly unfolded beneath him, Ed White was the first American human satellite.

Only a tether and a rather Buck Rogers-looking nitrogen gun for maneuvering kept him in the proximity of his mothership. And like a recalcitrant child, White did not want to come back inside when called. "This is the saddest moment of my life," he lamented. But return he did, and safely.

Much to the relief of the astronauts' wives, coincidentally both named Patricia.

Anticlimax

What do you do to top that? Well, while the rest of the flight might not have matched the drama of the main event, the remaining four days of the mission nevertheless were important, too. Not just for what was accomplished, but for what failed to be mastered.

For instance, Gemini 4 was supposed to get some rendezvous practice in, using the spent second-stage of the Titan as a target. Try as he might, McDivitt could not accomplish the task. Future pilots will be aided by radar; orbital mechanics are tricky!

Also, on the second and third days of the mission, McDivitt reported spotting and snapping shots of two satellites, one of which was just 10 miles away and had "big arms sticking out of it." However, the developed pictures do not show these mysterious craft.

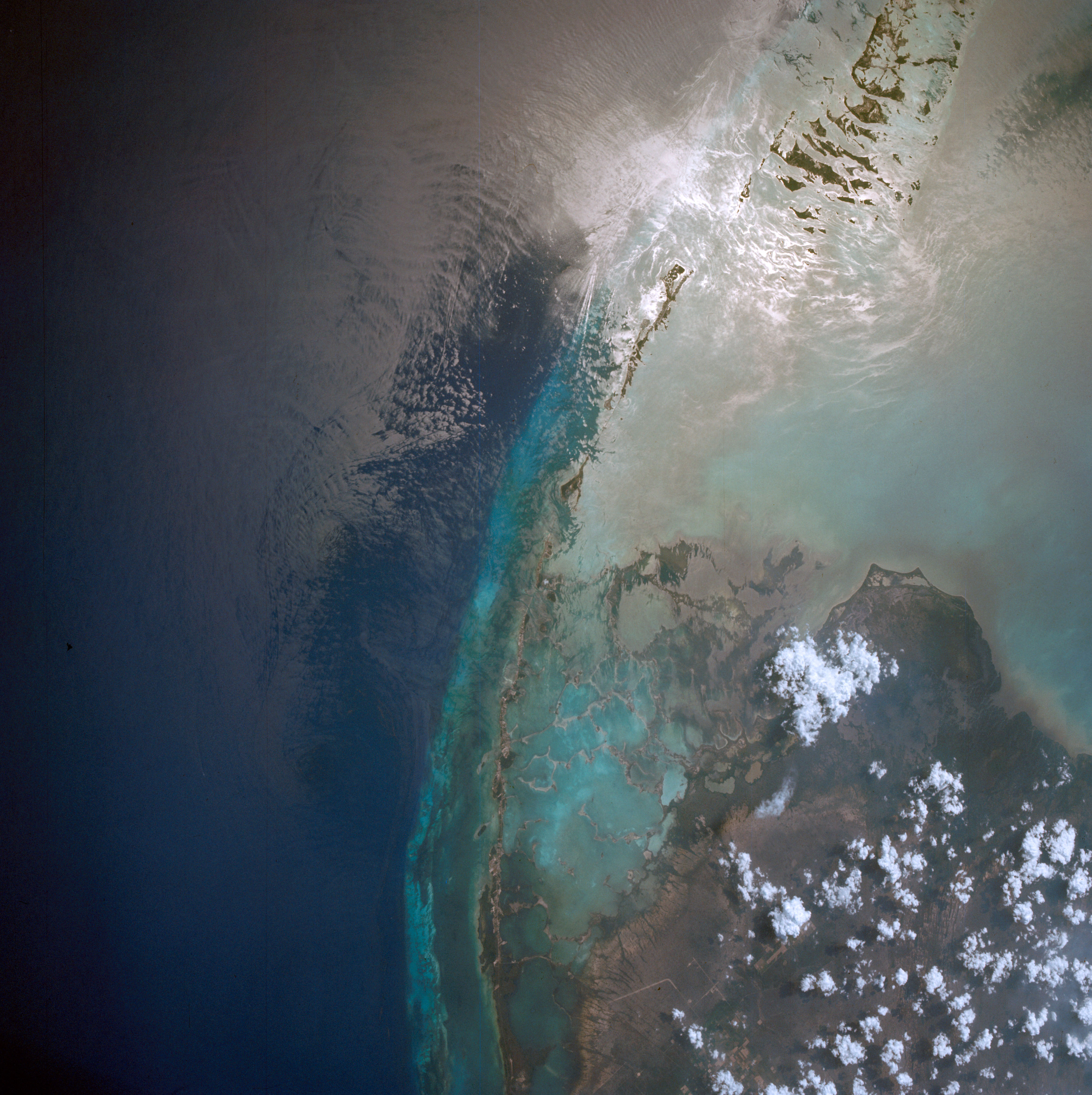

On the other hand, the Gemini crew did take amazing photos of the Earth, offering a sneak preview of the kind of gorgeous albums we can expect once human presence in space is firmly established. I will let the following sequence speak for itself.

Actually, I'll make a note on the following: the darkened area is rain that had recently fallen on Texas. This kind of Earth monitoring from orbit will be invaluable to science and business.

Trouble at the End

Gemini 4 was the first American (and possibly human, period) spacecraft to carry an onboard computer. This device was designed to provide a smooth and automatic landing. But on June 6, the day before landing, the computer became balky after receiving a software update, eventually quitting entirely.

A manual, Mercury-style reentry had to be done, which was begun around 9:45 AM on June 7. McDivitt was about a second late on the start of the procedure, and Gemini 4 ended up about 50 miles off target.

But the recovery fleet was already on hand when the parachute of McDivitt and White's capsule appeared in the noon-day blue, and within an hour of splash down, the astronauts and their ship were already onboard the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Wasp.

The doomsday predictions that long-term exposure to orbital radiation and weightlessness proved largely unfounded. The two astronauts were a little tired and wobbly, but on their own two feet, they marched below decks for a well-deserved shower.

Double is Something

In just a single flight, Gemini 4 more than doubled the accumulated American hours in space, quadrupled if you count them in human-hours. Gemini has demonstrated that the U.S. can deploy free men into space for extended periods of time, both inside and outside a capsule. And given the current flight schedule, with at least two, possibly three longer flights planned just for this year, there's no question that the American stride in the space race is lengthening.

Will the tortoise take the lead? Or is a bunny in the shape of Voskhod 3 about to upset the contest once again? Only time will tell.

Did you miss our stellar show on Gemini 4 and the Space Race? Tune into this rerun of The Journey Show!

![[June 8, 1965] A Walk in the Sun (the flight of Gemini 4)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650608Gemini_Four_patch-471x372.jpg)