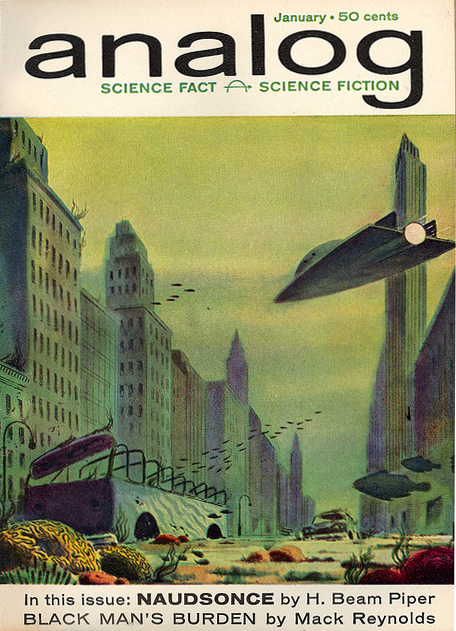

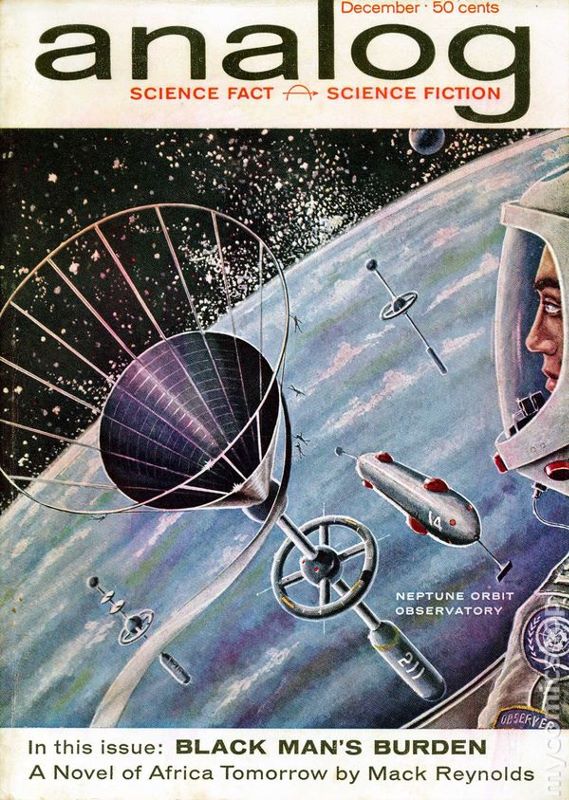

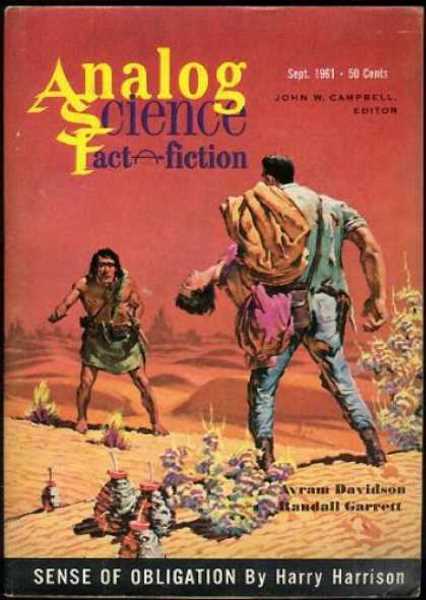

Has John W. Campbell lost his mind?

Twenty years ago, Campbell mentored some of science fiction's greats. His magazine, Astounding (now Analog), featured the most mature stories in the genre. He himself wrote some fine fiction.

What the hell happened? Now, in his dotage, he's used his editorial section to plump the fringiest pseudosciences: reactionless space drives, psionic circuits with no physical components, the assertion that the human form is the most perfect possible. The world hasn't seen an embarrassing decline like this since Sir Arthur Conan Doyle started chasing fairies.

But this month, Campbell has gone too far. This month, he replaced Analog's science-fact column with a rant on the space race, a full twenty pages of complete poppycock, so completely wrong in every way that I simply cannot let it lie.

Campbell's argument is as follows:

1) America could have had a man in space in 1951, but America is a democracy, and its populace (hence, the government) is too stupid to understand the value of space travel.

2) The government's efforts to put a man in space are all failures: Project Vanguard didn't work. Project Mercury won't go to orbit. Liquid-fueled rockets are pointless.

3) Ford motor company produced Project Farside, a series of solid-fueled "rock-oons," on the cheap, so therefore, the best way to get into space…nay…the only way is to give the reins to private industry.

Campbell isn't just wrong on every single one of these assertions. He's delusional.

Regarding #1:

There's a reason we didn't launch an astronaut in 1951. There was no point.

It is just conceivable that America could have put a man in space in 1951. It took six years of development to bring the Atlas ICBM from inception to fruition. Let's say that we, as a country, decided that the national objective after the fall of Fascism would be to put a fellow in space. Six years after the end of World War 2 is 1951; we might just have made it – if we didn't bother to make sure the rockets and satellites were safe enough for a man to fly in.

But to what end? What would have been the benefit? Why would we have engaged in one of the more expensive projects in history for the privilege of sailing a person in an orbital cannonball? Certainly, the scientific virtues of space travel had been barely conceived in 1945. There would have been no money in the endeavor. It would have been a stunt – a mass expenditure on a rickety aerospace infrastructure with no clear benefit to humanity. A boondoggle wisely avoided. The Soviets would have looked at our effort (and the likely trail of dead astronauts) and laughed.

So why do we have a non-military space program at all? Because we have a military missile program.

Both the United States and the Soviet Union saw the value of blowing up the other's cities on a moment's notice. Bombers are too slow and vulnerable. Missiles can do the job in half an hour and cannot be stopped. It is no coincidence that Sputnik first flew the year the first Soviet ICBM was finished, in 1957. The military mission was foremost, the civilian one a political afterthought.

Ditto our response. What booster lofted Explorer 1? The army's Redstone. Now, the American side had an unusual wrinkle. We actually had also developed a "civilian" booster, the Vanguard, to launch our first satellite. But Vanguard was a Navy-run affair and based on a Navy sounding rocket (the Viking, in turn based on the German V2). It didn't work right out of the gate, so the Redstone got the glory. Either way, our unmanned space program was only possible because of our military missile program.

Currently, both manned space programs depend on their related ICBM programs. Gagarin went up on a modification of the Sputnik missile. Deke Slayton (or another of the Mercury 7) will go up on an Atlas, when we feel it is safe enough. Both men are active-duty military officers.

Like it or not, the peaceful development of space is only possible because of the military value of space. There is no way either side would have spent this kind of dough on space travel just for the fun of it, or even for the potential scientific advancements.

Which leads me to assertion #2.

I couldn't believe my eyes when Campbell said Mercury is not an orbital space program. A quick perusal of an issue of Aviation Week, or even the daily newspaper, shows his assertion to be absurd.

Sure, Shepard's mission was, and the next two missions will be, suborbital ones. These are to test the spacecraft and their pilots (and also a vain attempt to achieve a space record before the Communists – we missed by four weeks). When Mercury is finished, it will have achieved the same goals as the Soviet Vostok program: to prove a man can survive for several days in space and come back safely.

Mercury's successor has already been announced. Apollo will be a three-person ship that will go around, and perhaps even land on, the moon. The Soviets have not announced a similar program, but then they only like to announce space shots after they've succeeded. Who knows how many failures they're hiding.

I have no doubt that an orbital Mercury will fly by next year. I also have no doubt that an Apollo will take a crew to the Moon "before this decade is out" (the President's recent words). I don't know where Campbell gets his information.

Campbell splutters that the Saturn moon rocket should be scrapped because liquid-fuel rockets are expensive failures, and Ford Motors likes solid-fuel rockets. Campbell has forgotten that the Farside rockets and the new solid-fueled Scout are just as unreliable as the Vanguard was when it started, and ICBM-strength solid-fueld rockets ain't cheap.

As for Vanguard being a failure, well, that's just not true either. After some expected teething troubles, Vanguard launched three satellites into orbit, two of which are still beep-beeping away. And guess what? Project Echo, the communications balloon that Campbell touts as the pinnacle of commercial space success, was launched by a Thor-Delta, our most reliable space booster. Know what the "Delta" is? It's the top half of a Vanguard. Some "failure. "

How about the "Thor" half? That's right. It's an Air Force missile. Some "private enterprise."

And that brings us to #3.

It's great that Ford Motor Company was able to launch a whopping six (count them!) sounding rockets from balloons, two of which actually worked. Yes, science can sometimes be done on the relative cheap.

Orbital missions cannot. It takes far more energy to keep an object circling the Earth than to shoot it up real high, something the editor of a science fiction magazine should understand. There's a reason no company has invested the kind of money it takes to develop a private IRBM, let alone a private ICBM: It's not worth it, liquid or solid fueled. That's not a matter of government jealousy, as Campbell maintains, or short-sightedness; it's simple economics. By the way, who paid for Operation Farside (and developed its booster components)? That's right. The government.

Private companies may build the rockets that get us into space. But it takes government money to interest a Convair or a Douglas in multi-year, hundred-million dollar projects. The space program is literally impossible without government involvement.

At least for now. It is possible that in fifty years or so, after the government-run space projects result in a mature, cheaper space industry, that private enterprise will pick up the slack. Rockets, nuclear engines, or anti-matter drives, will be inexpensive enough, and the commercial opportunities of space (communications, manufacturing, tourism) attractive enough, that we'll see PanAm space stations and TWA moon bases.

But it will take government investment first. The interstate highway, the jet, the rocket, the atomic power plant, all of these developments required massive government spending before they could become commercially sustainable realities.

Having shown every one of Campbell's points for the utter nonsense they are, we are left to wonder: What brought on Campbell's irrational rant? I think it's because Campbell, like a lot of Americans, is sore that our country seems to be behind in the Space Race.

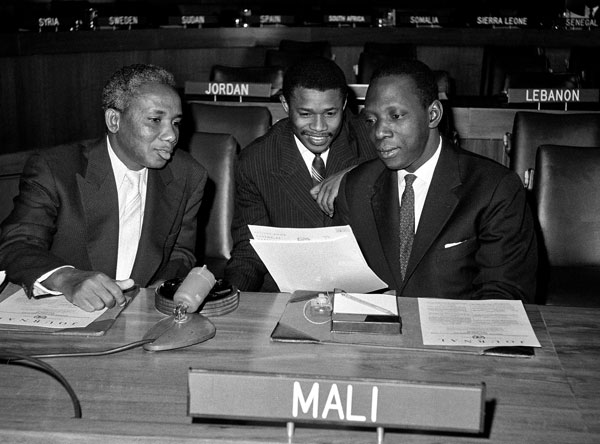

Are we really behind, though? I count the current operating satellite score at 9 to 0. Moreover, since 1957, we've launched 51 craft into orbit and beyond, the Soviets just 13. The Discoverer series alone numbers 26, a good half of which were successes. In other words, the CIA (with the help of the Air Force) has launched as many working flights as the entire Soviet Union!

Much is made of the fact that the Soviets launched the first satellite into orbit. In fact, the rocket that launched Explorer 1 was ready in 1956, a full year before Sputnik. Why did Eisenhower wait? Why didn't we seize the orbital high ground for a quick propaganda victory?

One: If we had, you can bet the Soviets would have made a stink in the UN about our having "violated" their air space. By letting the Russians beat us to the prize (by a paltry four months), Ike cleverly sidestepped this fight.

Two: The Soviets used a plainly military missile to launch their first space vehicle. Ike wanted the first American satellite to be lofted by a (technically) civilian platform. Had Sputnik never flown, or had it flown six months later, the first American satellite would have been a Vanguard, not an Explorer. We were more interested in preserving the moral high ground than being first.

In any event, Sputnik was no surprise. Both superpowers had announced their intention of flying a satellite in 1957-8. The Soviets announced their plans for the October 1957 launch two months prior. We announced our first orbital Vanguard flight would happen by the end of the year. Sputnik was a great achievement, but it was not a coup. The Soviet successes in space since then are admirable and should be applauded. Then they should be assessed in light of our successes.

It does no good to Chicken Little one's way to insanity. And that's what's happened to Campbell. He is not making a rational argument. He's not presenting science. He is throwing a tantrum.

Analog's readers deserve better from their "science fact" column.

So let me summarize:

Vanguard was and is a tremendous success. It's still working for us today.

Mercury is an orbital program in its suborbital phase. In a few months, we'll have an astronaut in orbit.

America's government-run space programs, all ten plus of them, are doing just fine.

Commercial interests could not and would not have achieved our current successes on their own.

Analog could use a new editor.