by Gideon Marcus

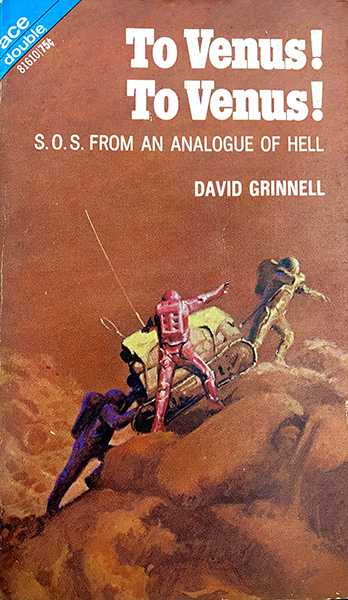

To Venus! To Venus!, by David Grinnell

cover by John Schoenherr

Warning: the latest Ace Double contains Communist propaganda!

The premise to David Grinnell's (actually Ace editor and Futurian Donald Wolheim) newest book is as follows: it is the 1980s, and the latest Soviet Venera has confirmed the initial findings of Venera 4, not only reporting lower temperatures and pressures than our Mariner 5, but spotting a region of oxygen, vegetation, and Earth-tropical climate.

And they're launching an manned expedition there in less than two months.

Continue reading [March 14, 1970] To Venus and Hell's Gate… are we Out of Our Minds?

![[March 14, 1970] <i>To Venus</i> and <i>Hell's Gate</i>… are we <i>Out of Our Minds</i>?](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700314covers-672x372.jpg)