by Gideon Marcus

A friend of mine inquired about an obscure science fiction story the other day. She expressed surprise that I had, in fact, read it, and wondered what my criteria were for choosing my reading material. I had to explain that I didn't have any: I read everything published as science fiction and/or fantasy.

My friend found this refrain from judgment admirable. I think it's just a form of insanity, particularly as it subjects me to frequent painful slogs. For instance, this month's Fantasy and Science Fiction continues the magazine's (occasionally abated) slide into the kaka. With the exception of a couple of pieces, it's bad. Beyond bad — dull.

The Issue at Hand

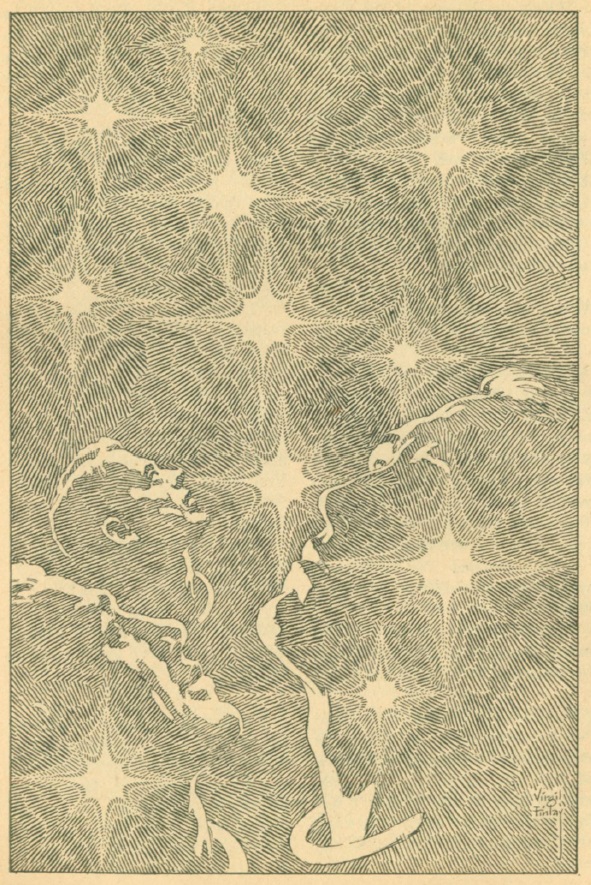

Cover by Jack Gaughan illustrating Into the Shop

Fred One, by James Ransom

We start off on reasonably sound footing, with a pair of preternaturally intelligent laboratory rats named Freds One and Two. One is a genius, the brains of the operation. The other, though possessed of a high order of intelligence for his kind, is clearly a sidekick. It is not made clear whether the rats gained their smarts as a result of human intervention, or if they've always been bright and endure testing for their own reasons.

Not much happens, really. The author relies on the humor of the conceit, writing with deadly earnestness from the brain rat's point of view. The result is a fun but somewhat inconsequential story. It might make a good cartoon someday.

Three stars.

Beware of the Dog, by Gahan Wilson

Here's a one-page vignette that's far better than the monthly Feghoots (which have recently stopped being produced). I found it funny enough to read to my daughter.

Four stars.

Sun Creation, by B. Traven

Author Traven is some kind of ethnologist, a German who transplanted himself to Mexico and now translates native creation myths. Sun Creation is about a brave warrior who makes a new sun after the old one is devoured by evil spirits; it's as good (if not better) than any of the Greek myths I grew up with. I don't know if it belongs in this magazine, but it was my favorite piece of the issue.

Four stars.

A Piece of the Action, by Isaac Asimov

And now begins our downward slide. The Good Doctor, brilliant as he may be in chemistry, has oft confessed to having a blind spot when it comes to math. This is especially unfortunate as regards to this month's article, in which he tries to explain quantum mechanics and the discovery of Planck's constant.

The problem is, there are just some things you can't explain without math. I remember being bored and frustrated with high school physics; it wasn't until college, when they taught us the calculus-based stuff that things really clicked. I went on to take quantum mechanics my junior year in college (as part of an astrophysics curriculum). Let me tell you, it is a subject that is absolutely beautiful with the proper mathematical underpinning…and utterly meaningless without it.

Asimov's explanation of the subject, bereft of any math, doesn't work. I was barely able to follow along thanks to my prior education. I can't imagine any of his readers will be able to make much of it.

My first two-star score for Dr. A.

Welcome, Comrade, by Simon Bagley

Ugh continues. Here's a piece about a top secret project to orbit a brainwashing satellite. The goal is to instill every human on Earth with a love for and inability to sway from American values. You know: capitalism, democracy, and dispute resolution by fisticuffs. The title gives away the ending, which you'd have seen miles away anyhow.

Decent beginning, Analog-esque middle (especially if Bagley'd played it straight rather than satire), numbskull predictable ending.

Two stars.

Urgent Message for Mr. Prosser, by J. P. Sellers

Night watchman, so British that the rendition seems farcical, receives breathless calls at 1 AM. The caller urgently desires to warn Mr. Prosser, the watchman's boss, that he is in danger of being poisoned by his wife. Our protagonist meets with the caller one night and finds that he is, in fact, a dead ringer for Mr. Prosser.

The odd situation is never explained, though my guess is the caller is some sort of phantom made real out of the real Prosser's paranoid fears. In any event, this is another facile story that doesn't do much but mildly entertain and take up pages. Three stars, I suppose.

Van Allen Belts, by Theodore L. Thomas

I'm not sure why Thomas has this column; it's never worth reading. This one, like all his others, starts like a non-fiction article and ends with a science fictional tail-sting. Thomas recommends that the electrical current created by the charged particles circling the Earth could power satellites. This is nonsense — the sun's photons provide far more energy than the weak fields in orbit could ever provide.

One star and stop wasting my time.

The Old Man Lay Down, by Sonya Dorman

A poem by an author I generally look forward to. I couldn't make heads or tails of it. Explain it to me? Two stars.

The Crazy Mathematician, by R. Underwood

Mad scientist finds a way to travel the universes by way of a shrinking machine. He takes a handsome journalist along on his journeys, who spends the trip romancing the various versions of femininity he finds at the various stops.

Complete fantasy and not worth your energy. Two stars.

Fanzine Fanfaronade, by Terry Carr

The third in F&SF's series on fandom, it is neither as good as last month's (on conventions), nor as mediocre as the one from the month before (on fandom in general).

Three stars.

The Compleat Consumators, by Alan E. Nourse

The premise to this piece is that two lovers, ideally matched, will not just become one metaphorically, but will fuse into a single physical identity. It's a lovely idea, but here it's played for horror, and abandoned right when it could have become interesting.

Two stars.

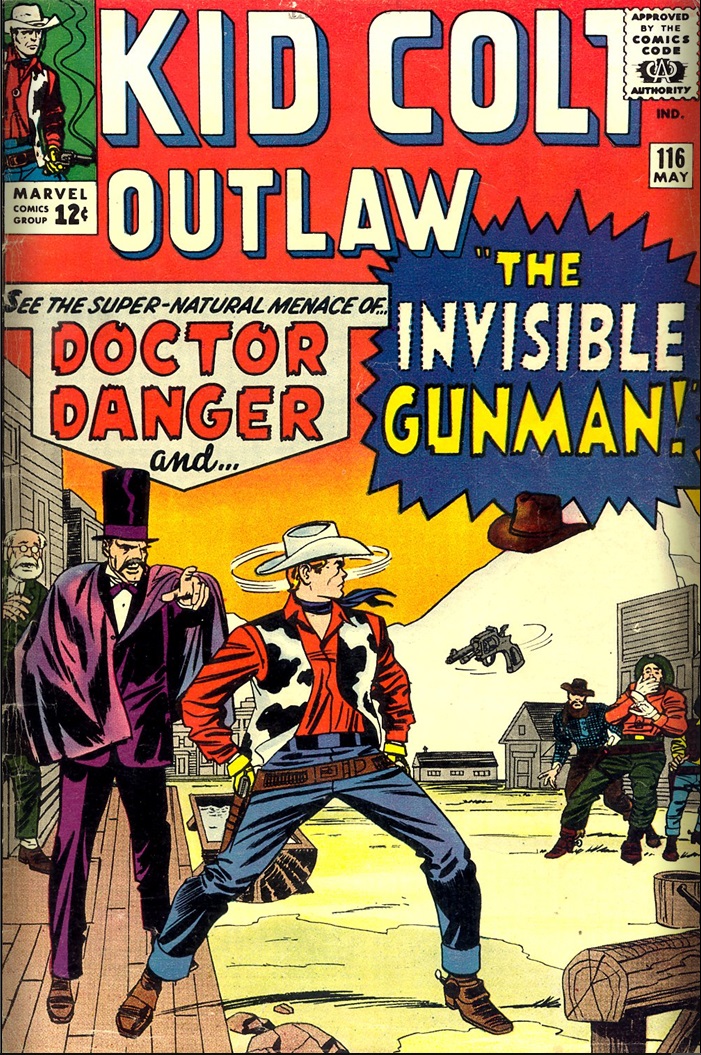

Into the Shop, by Ron Goulart

Intelligent cop car mistakes everyone for a suspect, including its human partner, with fatal results. Sub-par stuff, and doubly disappointing given Goulart's fine reputation.

Two stars.

Oreste, by Henry Shultz

And here we hit the bottom with a reprint from 1952(!) about an eight year old child and the odd uncle with whom he has a telepathic connection. It seems young Titus is stealing the thoughts of Uncle Oreste, writing books and composing music on borrowed talent.

Or something. There's a twist ending, but after 20+ pages of a story that could easily have fit into five, I was too bored to care.

One star.

Summing Up

Oh dear. Didn't I pledge just last month to be a lot nicer in my reviews? I guess there's something about reading eighty pages of muck that puts me in a bad mood. Like Uncle Oreste, someone has stolen my beautiful F&SF (my favorite magazine until Editor Davidson showed up in '62), and replaced it with nonsense.

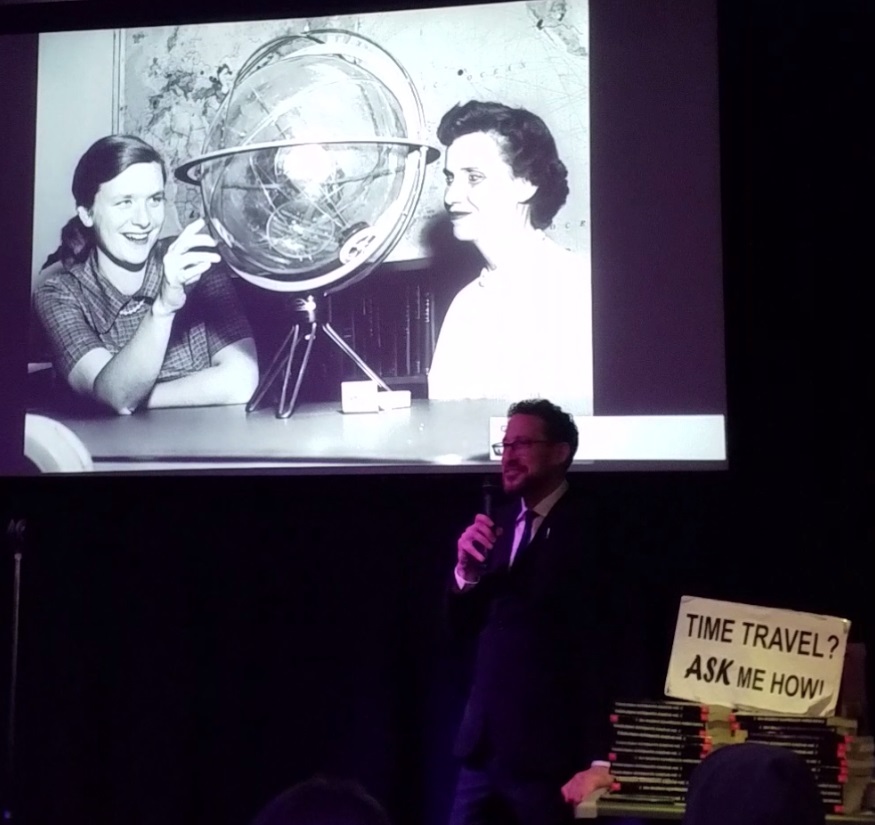

I do bring one piece of good news, though. I've got prints of my performance at San Diego Comic Fest. If you've got a sound-capable 8mm, let me know, and I'll Parcel Post it to you:

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[March 17, 1964] It's all Downhill(April 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640317cover-667x372.jpg)

![[March 15th, 1964] Maaaarco! (<i>Doctor Who</i>: Marco Polo, Parts 1 to 4)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640315butwherearethelittlehorses-672x372.jpg)

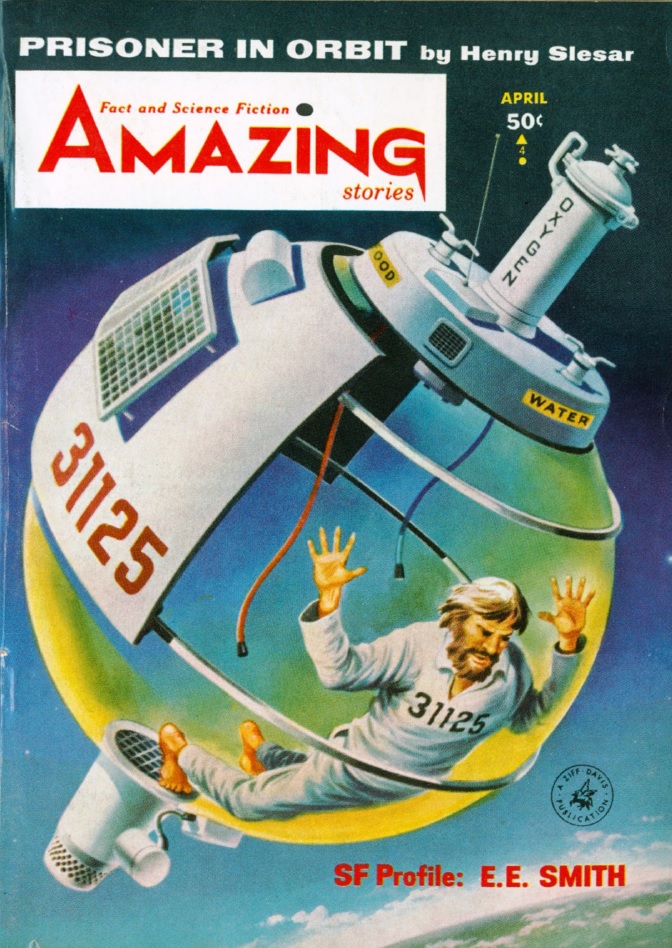

![[March 13, 1964] NOTHING MUCH TO SAY (the April 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640313cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 11, 1964] Brought into Focus (<i>The Outer Limits</i>, Season 1, Episodes 21-24)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640311d-672x372.jpg)

![[March 9, 1964] Deviant from the Norm (April 1964 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640309cover-672x372.jpg)

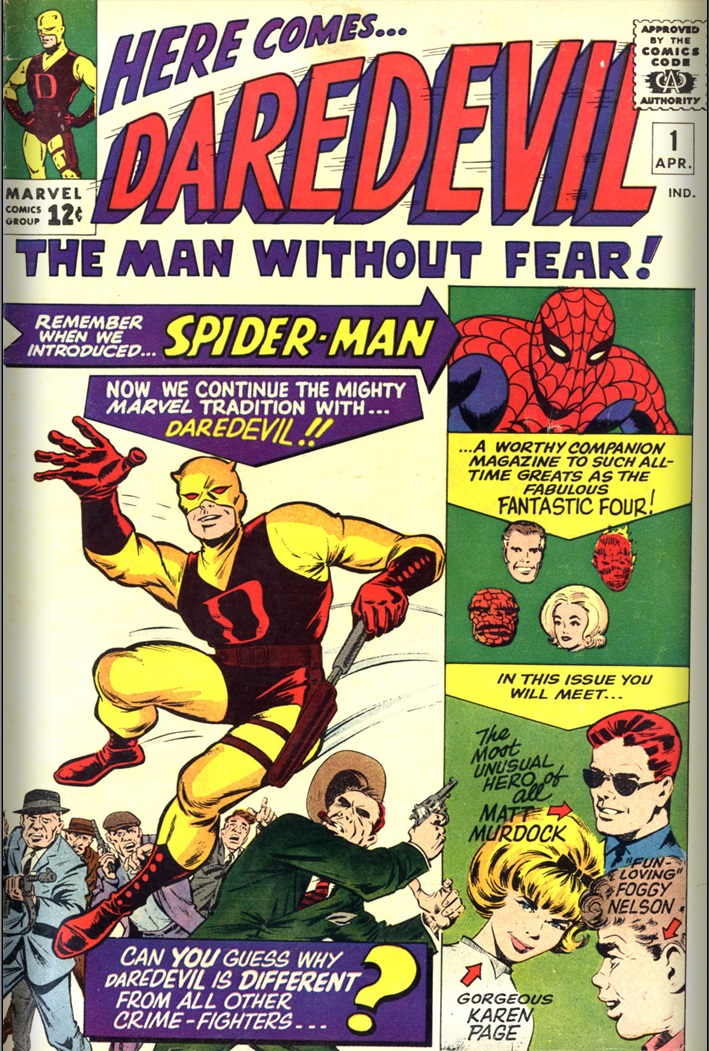

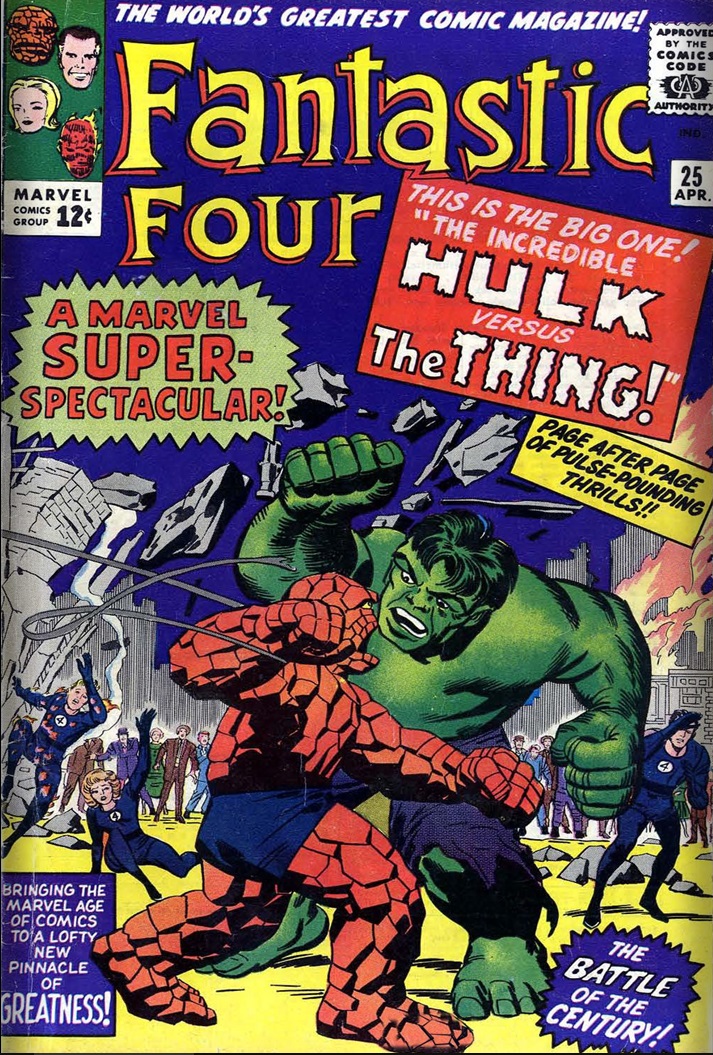

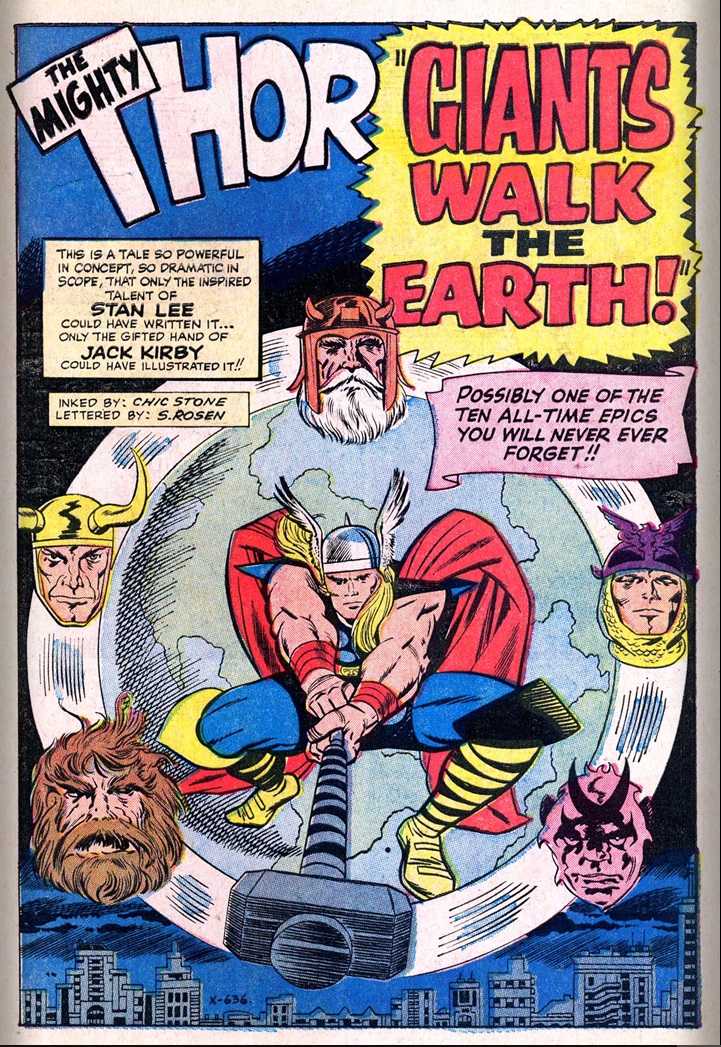

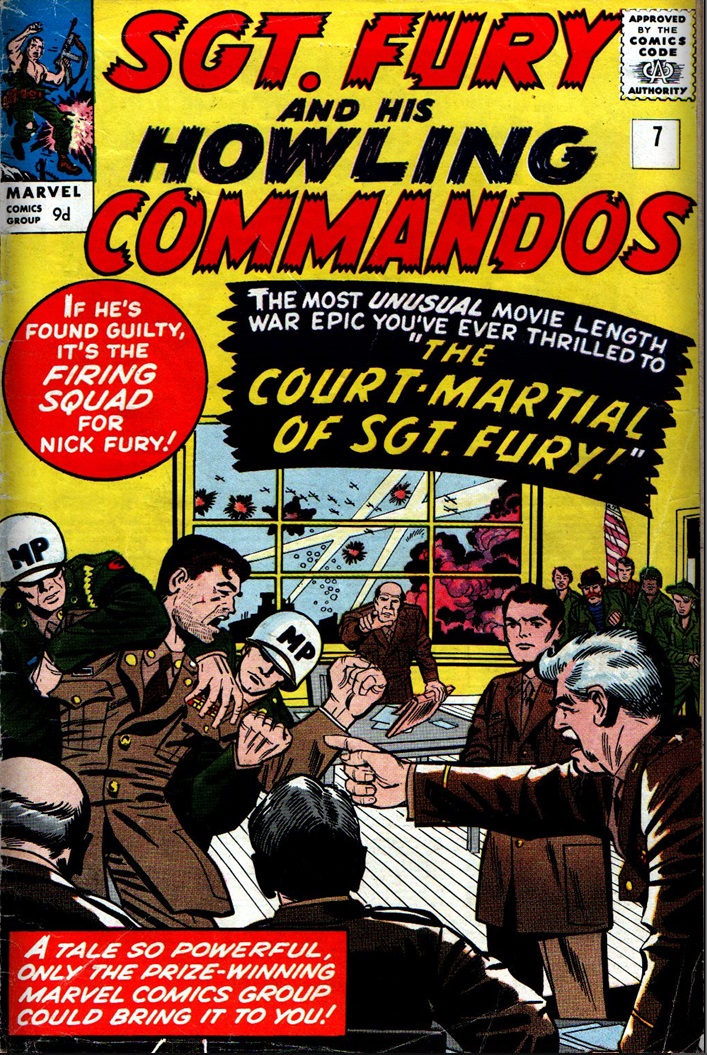

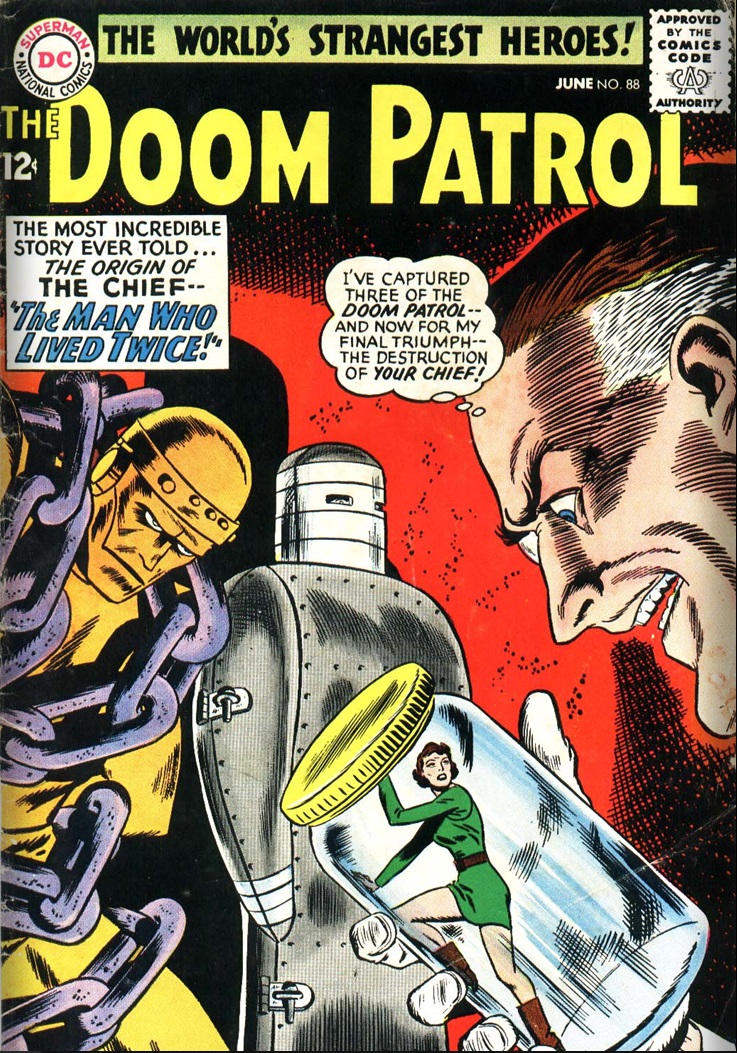

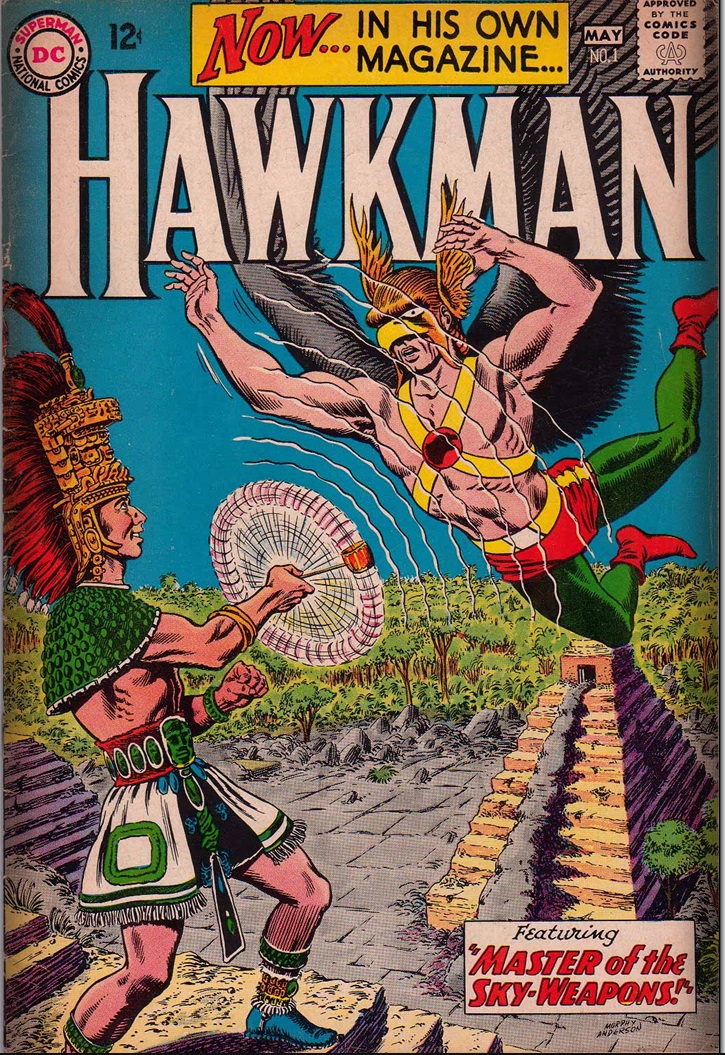

![[March 7, 1964] Look both ways (Marvel and National Comics round-up)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640301dd-672x372.jpg)

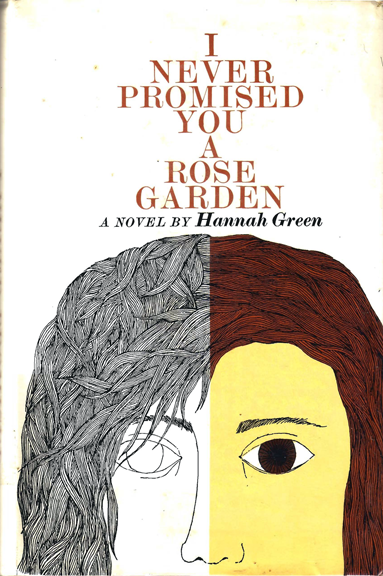

![[March 5, 1964] Brushwinged, I Soar (Hannah Green's I Never Promised You a Rose Garden)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640305RoseGarden_Cover-383x372.png)

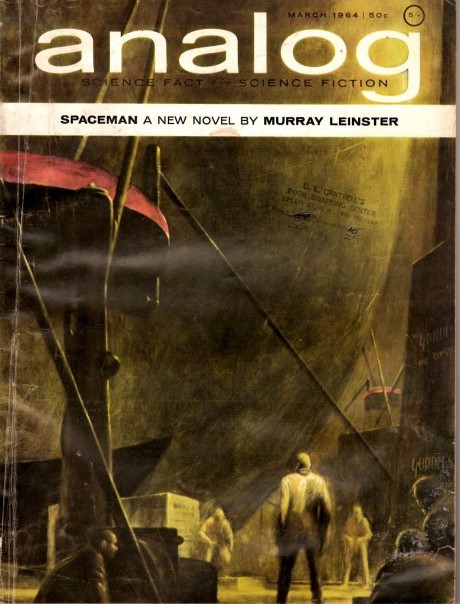

![[March 3, 1964] Out and about (March 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640303cover-460x372.jpg)

![[February 29, 1964] Think Twice — it's not all right (<i>The Twilight Zone</i>, Season 5, Episodes 17-20)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640229f-672x372.jpg)

![[February 27, 1964] Beatles, Boredom and Ballard ( <i>New Worlds, March 1964</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640227cover-649x372.jpg)