For most people, the beginning of the month coincides with the 1st (or, as my late father might say, the “oneth”—i.e., May the “oneth” followed by May the “tooth”). For me, and doubtless for most of my science fiction loving sistren and brethren, the month starts around the 26th, which is when the science fiction magazines hit the newsstands.

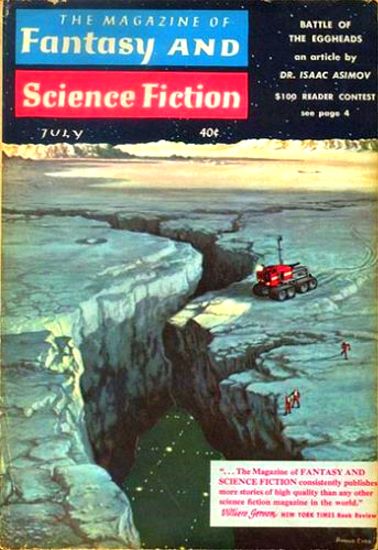

Of course, those who get their issues via mail-order get them at varying times, but in general, the last week of the month preceding the month preceding the cover date (I did not stutter; the duplication is intentional) is when the goodies arrive. For me, that’s The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (generally good), Astounding Science Fiction (often bad, but sometimes good), and on a bi-monthly and alternating basis, Galaxy (generally decent), and IF (quality as yet undetermined). When these run out, I pray for interesting space news and/or interesting new novels. Exhausting these, I turn to my collection of older books, preferably ones I have been given the right to distribute freely.

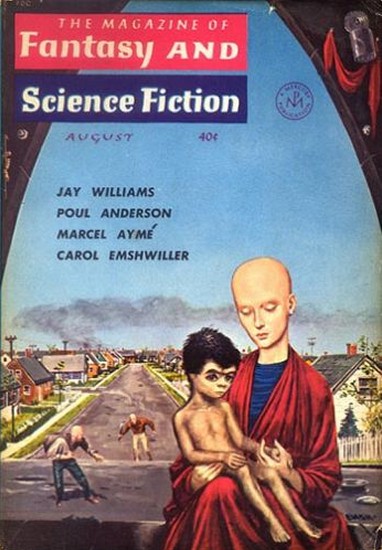

I am currently at the giddy start of a new month, and I’ve decided to eat my dessert first, tearing through the August 1959 F&SF. Take my hand, and away we go!

Jay Williams generally sticks to juveniles, co-writing the Danny Dunn series, which are pretty fun if you’re the right age to enjoy them (pre-teen). His Operation LadyBird opens up this month’s issue, and it’s a lighthearted romp on a Venus that a United Nations force has recently cleaned of a loathsome alien menace. Turns out that we were actually called in (unwittingly) by Venusians (who look just like Hopi Indians) to act as exterminators. I liked the story better when it was called Cat and Mouse, but the story is not without its charms, and it does feature a strong female character, a resourceful Soviet major.

Asimov’s column is good this month. The Ultimate Split of the Second begins as a primer on measuring really big and small things. The Doctor recommends using the time it takes light to travel certain small distances as really small units of time (i.e. a light meter, a light kilometer, etc.). This the flip side to using light years, minutes, hours, for distance measuring.

Then he gives us a survey of the latest discoveries of subatomic particles, exciting new things that are the very bleeding edge of modern physics. Their halflives are exceedingly small, so the nomenclature described above comes in handy to describe them.

The prolific Carol Emshwiller (whose husband’s art graces the pages of many digests under the byline “EMSH”) has an interesting post-apocalyptic mood piece called Day at the Beach. There’s not much to it; it is largely the depiction of a family in a ruined, but not extinguished, United States. Gasoline is exorbitantly expensive, most citizens have lost all of their hair, mutations are legion, and there is not much law and order. Diverting, forgettable.

Fantasist Marcel Aymé’s The Walker-Through-Walls is cute, though it is a reprint from 1943. Our straight-laced protagonist discovers that, in mid-life, he has the ability to traverse walls as if they did not exist. He resists exploiting this power, but little by little, he succumbs to temptation. First, he terrifies his tyrannical boss, then he becomes a dashing, popular thief. Ultimately, he becomes involved in a torrid affair that proves to be his undoing. Well-written, somewhat fluffy.

Finally, for today, we have Poul Anderson’s latest Time Patrol story. As you know, I have a bit of a love-hate relationship with the good Swede, but this one is pretty good. For those who don’t know, the Time Patrol is an organization based in the far future that recruits constables from across time to police for alterations in the timeline. It’s a tough task, but it is made easier by the laws of the universe which have the time stream move along in a way not unlike a river—it takes a lot to get a substantial altering of course.

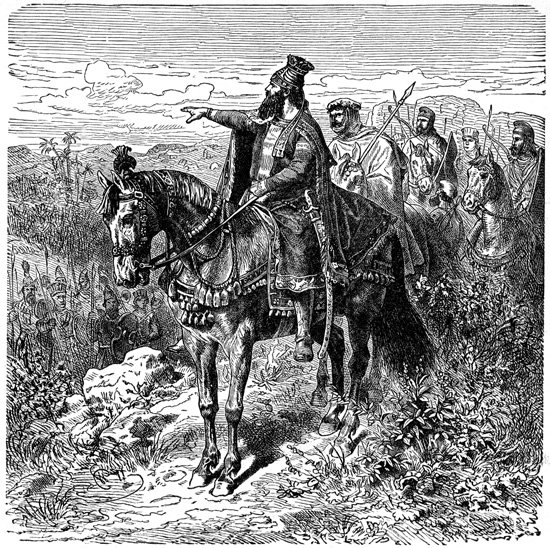

Patrolman Manse Everard, nominally stationed in the late ‘50s, is approached by Cynthia, wife of his best friend, and object of Manse’s unrequited affections, to find her husband, who has disappeared without a trace some 2500 years in the past. Unable to say no, Manse takes an unauthorized trip to the Persian Empire of Cyrus the Great to find his friend, who turns out to be none other than the King of Kings himself! It’s an exciting but somewhat ironic and bittersweet story, and it gets extra stars for being about a rather unsung but personal favorite era of mine.

All told, the first half (and a little extra) of this issue has had no clunkers, but also no home runs, to mix my metaphors. Call it 3.5?

See you in two days!

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has comments. Please comment here or there.