by Cora Buhlert

In my last article, I gave an overview of science fiction novels from beyond the Iron Curtain, including the works of Polish author Stanislaw Lem. Today I will take a look at a recent East German/Polish movie based on one of Lem's novels.

It will probably surprise you that Eastern Europe has a tradition of fantastic cinema, particularly stunning fairy tale movies that can wow even Western audiences. In fact, the state-owned East German DEFA studios has produced lots of live action fairy tale movies and stop motion puppet films since 1946.

Eventually, the DEFA decided to use the technical expertise gained from making fairy tale movies and apply it to science fiction. In 1957, director Kurt Maetzig announced that he planned to adapt Stanislaw Lem's novel Astronauci (Astronauts), published as Planet des Todes (Planet of Death) in German. Maetzig even hired Lem to write an early draft of the script.

Kurt Maetzig is not a natural choice for East Germany's first science fiction movie, since he is mostly known for realist fare and even outright propaganda films. Though the fact that Maetzig is a staunch Communist helped him overcome the reservations of DEFA political director Herbert Volkmann, who doesn’t like science fiction, since it does not advance the Communist project and who shot down eleven script drafts as well as Maetzig’s plan to hire West European stars.

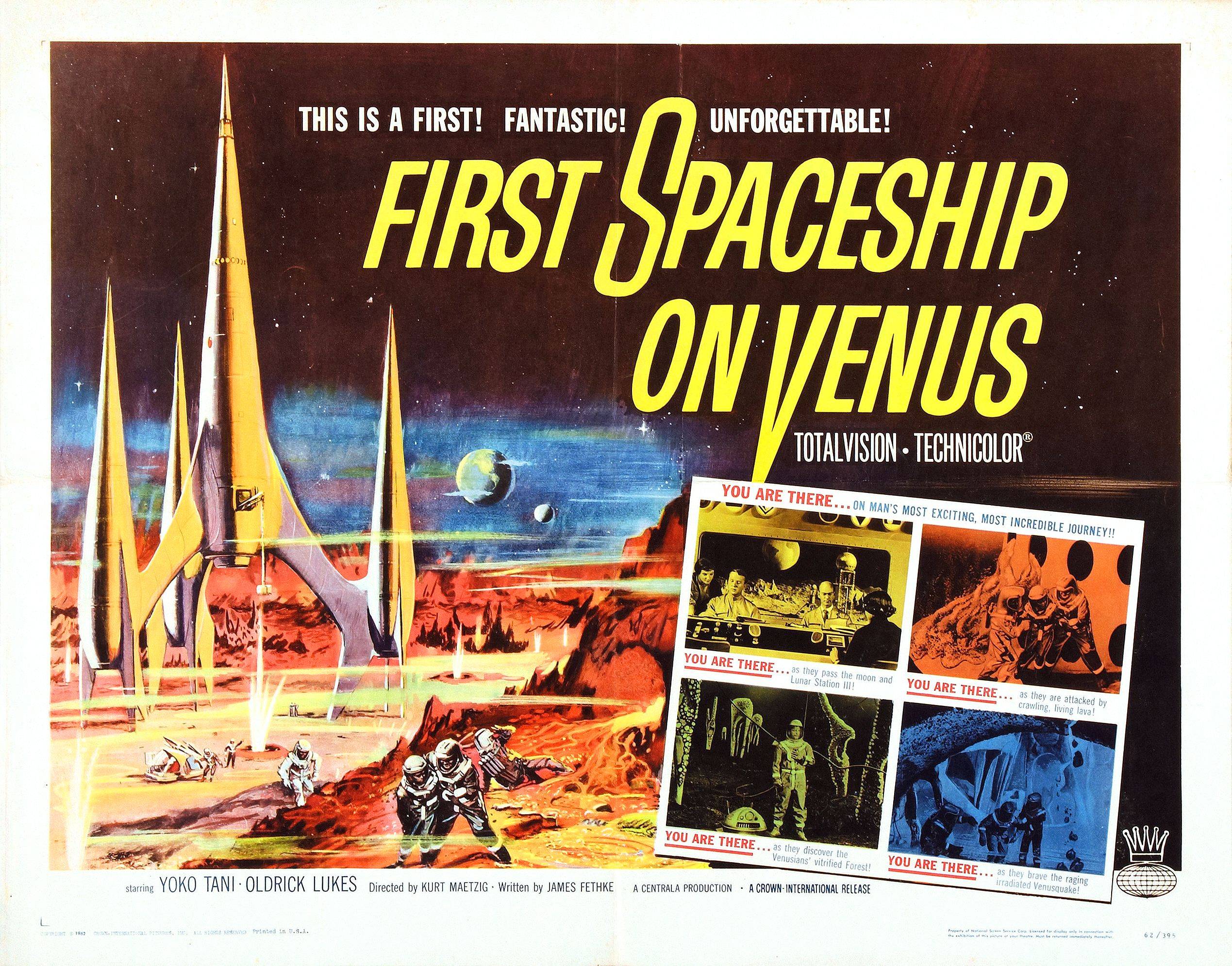

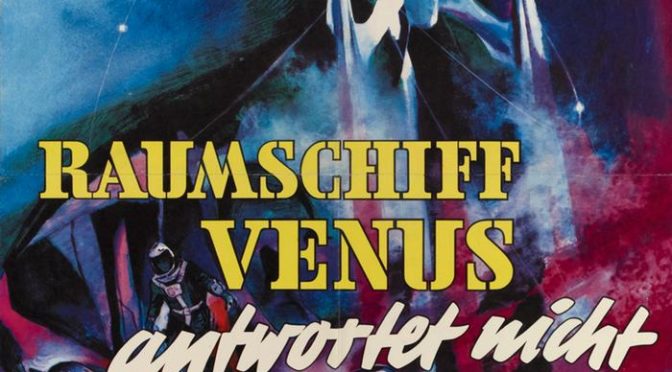

Slated for 1958, the film, now called Der schweigende Stern (The Silent Star), finally premiered in February 1960. Stanislaw Lem reportedly did not like the movie at all. Nonetheless, it became a success and also played in West Germany under the title Raumschiff Venus Antwortet Nicht (Spaceship Venus does not reply).

The Silent Star begins in the not so far off future of 1970, unlike the novel, which is set in the somewhat further off future of 2003. During excavation work, a mysterious coil with a recording in an unknown language is found. Scientists realise that the message originates on Venus and came to Earth when a spaceship crashed in the Tunguska region in Siberia in 1908.

Once humanity is aware of a civilisation on Venus, they try to establish communication. However, Venus does not reply. Therefore, it is decided to send a spaceship. Luckily, the Soviet Union just happens to have one and kindly donates it to an international Venus mission. This spaceship, the Kosmokrator, must be the prettiest rocket ship ever seen on screen. It looks as if a Hugo Award sprouted three baby Hugos.

The multinational crew consists of Russian astronomer Professor Arsenyew (Michail N. Postnikow), Polish engineer Soltyk (Ignacy Machowski) and his robot Omega, German pilot Raimund Brinkmann (Günther Simon), Indian mathematician Professor Sikarna (Kurt Rackelmann), Chinese linguist and biologist Dr. Chen Yu (Hua-Ta Tang), African communications technician Talua (Julius Ongewe) and the only woman on board, Japanese doctor Sumiko Ogimura (Yoko Tani).

The Kosmokrator crew even includes an American, nuclear physicist Professor Harringway Hawling (Oldrich Lukes), who joins the mission against the wishes of a group of cartoonish American capitalists. The only American willing to support Hawling is his mentor Professor Weimann (Eduard von Winterstein), who hoped to harness nuclear power, but was forced to build nuclear weapons instead. Weimann tells the assembled cartoon capitalists, "Hiroshima was your adventure. His adventure is the mission to Venus."

This is not the only mention of Hiroshima in the movie. Sumiko lost her mother in Hiroshima and was rendered infertile due to radiation exposure, which causes her a lot of angst and also torpedoes her budding romance with Brinkmann, who thinks that she shouldn't be aboard the ship because a woman's place is to bear children. Meanwhile, the fact that the Soviet Union has nuclear weapons and that the People's Republic of China is working on them is not mentioned at all. Apparently, nuclear weapons are only bad when in the hands of Americans.

These propaganda bits are eyerollingly blunt, but the Kosmokrator's multinational crew offers a positive vision of a future where the world's powers are no longer rivals in the space race (cartoon capitalists notwithstanding) but work together. Furthermore, the Kosmokrator's crew includes members from the emerging nations of Asia and Africa, which is a big step forward compared to the all-male, all-white and all-American crew seen in Forbidden Planet. I wonder when we will see Russian, Japanese or African astronauts aboard western spaceships, whether in fiction or reality.

A crew of scientists, every single one of them the very best in their respective fields, seems like a good idea in theory, but the characters remain bland and I had to dig up my program book to recall their names.

Arsenyew and Brinkmann are both square-jawed and heroic to the point of caricature. The balding engineer Soltyk is memorable because he doesn't fit the image of a heroic astronaut. Sikarna and Hawling are serious scientists. Chen Yu and Talua are given little to do until the end. Sumiko, the only female character of note in the film, mainly exists to angst about her infertility. Even the robot,Omega,is dull.

Once the mission gets underway, the Kosmokrator crew faces the usual perils of space travel such as a meteorite shower and a risky repair in space. They also manage to decipher the message and realise that the Venusians had planned to nuke Earth from orbit in 1908, when their ship crashed. The crew withholds this crucial information from the authorities to avoid causing a panic. They also decide to continue their mission to see if the Venusians have learned the error of their warlike ways.

When the Kosmokrator reaches Venus, the crew still cannot contact anybody and their sensors cannot penetrate the dense cloud cover. Brinkmann and the robot scout ahead, but lose contact with the ship and so the Kosmokrator lands after all.

The crew finds a bizarre Venusian landscape, including a radioactive "glass forest", a glowing sphere and a cave full of metallic spiders, which they initially mistake for lifeforms, but which turn out to be mechanical and part of a Venusian archive.

Chen Yu figures out that the radioactive forest is not biological either, but a gigantic nuclear cannon. Chen Yu and Sikarna also decipher the Venusian archive and realise that many recordings abruptly break off, as if Venus was hit by a massive catastrophe.

You'd think that these alarming discoveries would persuade the Kosmokrator crew to get the hell out of there. However, our brave astronauts continue their explorations and discover a ruined city. They also finally catch a glimpse of some Venusians in the form of humanoid blast shadows. And just in case the viewer might have forgotten, Sumiko reminds us that she saw similar blast shadows in Hiroshima.

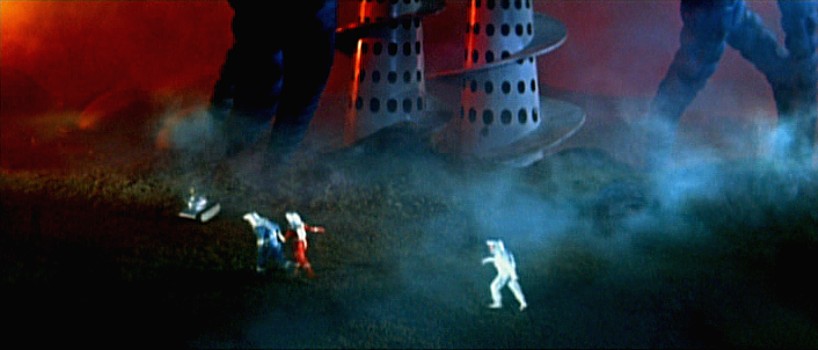

The Venus scenes – shot in Agfacolor and Totalvision – are the highlight of the movie and can compete with anything Hollywood produces. The DEFA team managed to create a dreamlike alien landscape that is reminiscent of modern art. The radioactive forest and the ruined city are influenced by the paintings of Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró and Paul Klee. The glowing sphere is based on the geodesic dome designs of Buckminster Fuller, while the Venusian blast shadows are reminiscent of the sculptures of Alberto Giacometti.

In the ruined city, Arsenyew and Hawling come upon the targeting system for the nuclear cannon, while Brinkmann, Soltyk and Sumiko are chased up a spiralling tower by a burbling mass (portrayed by the entire annual East German production of glue, which must have screwed up the plan fulfilment of several industries), which recedes when Soltyk fires at it. At the same time, both the sphere and the targeting system activate. Uh-oh.

Though the Kosmokrator's crew consists of Earth's best and brightest, it takes them a long time to catch on to what is happening. In fact, I suspect that many viewers have figured out the mystery long before the crew does, namely that the Venusians managed to blow themselves up during their attempt to nuke Earth in 1908. However, their cannon is still functional and still aimed at Earth. And our blundering astronauts managed to reactivate it.

The rest of the movie is a race against time, as the Kosmokrator crew scrambles to deactivate the nuclear cannon and the glowing sphere which turns out to be a gravity device holding the Kosmokrator captive. And as if all that wasn't enough, the radiation also causes the robot Omega to run amok.

Chen Yu and Talua deactivate the system, but Chen Yu damages his space suit. Brinkmann takes off to rescue him, but it's too late. The gravity field created by the sphere reverses and hurls the Kosmokrator back into space. Brinkmann is lost and Chen Yu perishes, while Talua is left standing alone on a dead planet.

These heroic deaths should be a lot more affecting than they are. But the climactic scenes feel rushed, especially compared to the staid pace of the rest of the movie. The crew seems unaffected as well. Hence, Sumiko tells the dying Chen Yu that the Venusian seeds he found have sprouted, which will be a great comfort to him as he suffocates. Finally, the film cuts straight to the landing on Earth, where the surviving crewmembers sum up the moral of the story, before the movie ends with everybody holding hands.

"War will only destroy the aggressor" is a popular theme in East European science fiction and may also be found in the West. Rocketship X-M has a similar plot, but set on Mars rather than Venus. Forbidden Planet features another alien civilisation that managed to destroy itself, though by harnessing the power of the mind rather than the power of the atom. I have no idea if Lem or Maetzig have seen either movie, but the similarities are striking. Fear of nuclear war is another common theme in both East and West, which I find heartening if only because knowing that both sides share this fear makes it less likely that someone will press that button.

Spaceships with multiracial and multinational crews can be found in both Eastern and Western Europe, whether in the works of Stanislaw Lem, Eberhard del'Antonio and Carlos Rasch and West Germany's Perry Rhodan series. I wish that American science fiction would follow suit because the future should have room for everybody and not just for Americans and Russians.

American and British viewers did have a chance to watch The Silent Star, for the movie was distributed in the US and UK under the title First Spaceship to Venus, though the US/UK edit is about ten minutes shorter than the original, because the propaganda bits such as the scene with the capitalists as well as all Hiroshima references were cut.

So if you happen to come across The Silent Star a.k.a. First Spaceship to Venus in a movie theatre, should you watch it? I'd say yes, because in spite of its weaknesses, The Silent Star is an interesting science fiction movie with stunning visuals. British and American viewers lose ten minutes of propaganda dialogue, but that's not that much of a loss.

Three and a half stars.

Thanks for the review. Seems lworth watching for the historical value.

It's certainly interesting and well made, in spite of several corny moments.

I managed to catch a showing of the truncated American version, and it is very interesting indeed. The visuals are completely different from any SF film made on this side of the Iron Curtain.

Well, you're not missing too much, if you've only seen the US/UK edit, unless you're really keen on propaganda laden dialogue. The scene with Hawling and the capitalists is at least unintentionally funny, but some of the Hiroshima stuff is eyeroll worthy even to someone like me who is highly critical of nuclear weapons and nuclear power.

Besides, it's the visuals that make the movie and those survived the edits intact, unless they cut out the Venuasin blast shadows.

I still remember watching this movie on TV when I was a child. It is still a good movie, I have not watched it in a long time and it is defiantly worth a second look. I will have to watch it again sometime in the future.

It's definitely worth a second look.

Great review! I agree with your sentiments about the film. I saw it when I was very young, had no idea what was going on. I was fascinated by the robot, but the film as a whole scared me! I managed to find a DVD years later and had it shipped from the US to UK. Even as an adult I found it scary! but also visually incredible. The very first thing I ever bought on Ebay was the original US film poster and later the original FoH stills. I did hear that the German version was longer than the US edited film I have. I'd LOVE to see the German version!

Is there an HD release of the original, uncut version available? I've had the DVD for years, but the SD, non-anamorphic, letterbox format was disappointing.