by Margarita Mospanova

Hello, dear readers!

Do you have books that you’ve always wanted to read but never got the chance to? Books that you’ve heard so much about they’ve long since made their place in your bookish plans and budgets, but haven’t quite managed to reach your hands?

The reason these books remain unopened still might be lack of time. Not quite full wallet. Or simply their absence from the nearest bookstore. But in my case, the reason often was censorship.

It won’t come as a surprise to many of you, but being a published author in the USSR almost unfailingly meant having to obey various rules and regulations of the people in power, written or unwritten. As such, many of the titles that I undoubtedly would have greatly enjoyed at the time were rebuffed by the editors before they even saw the light of day.

Now that I no longer reside in the Soviet Union, obtaining Soviet books is even harder. However, some of them were fortunate enough to trickle through the borders, with or without their authors. And here we come to the subject of this humble review.

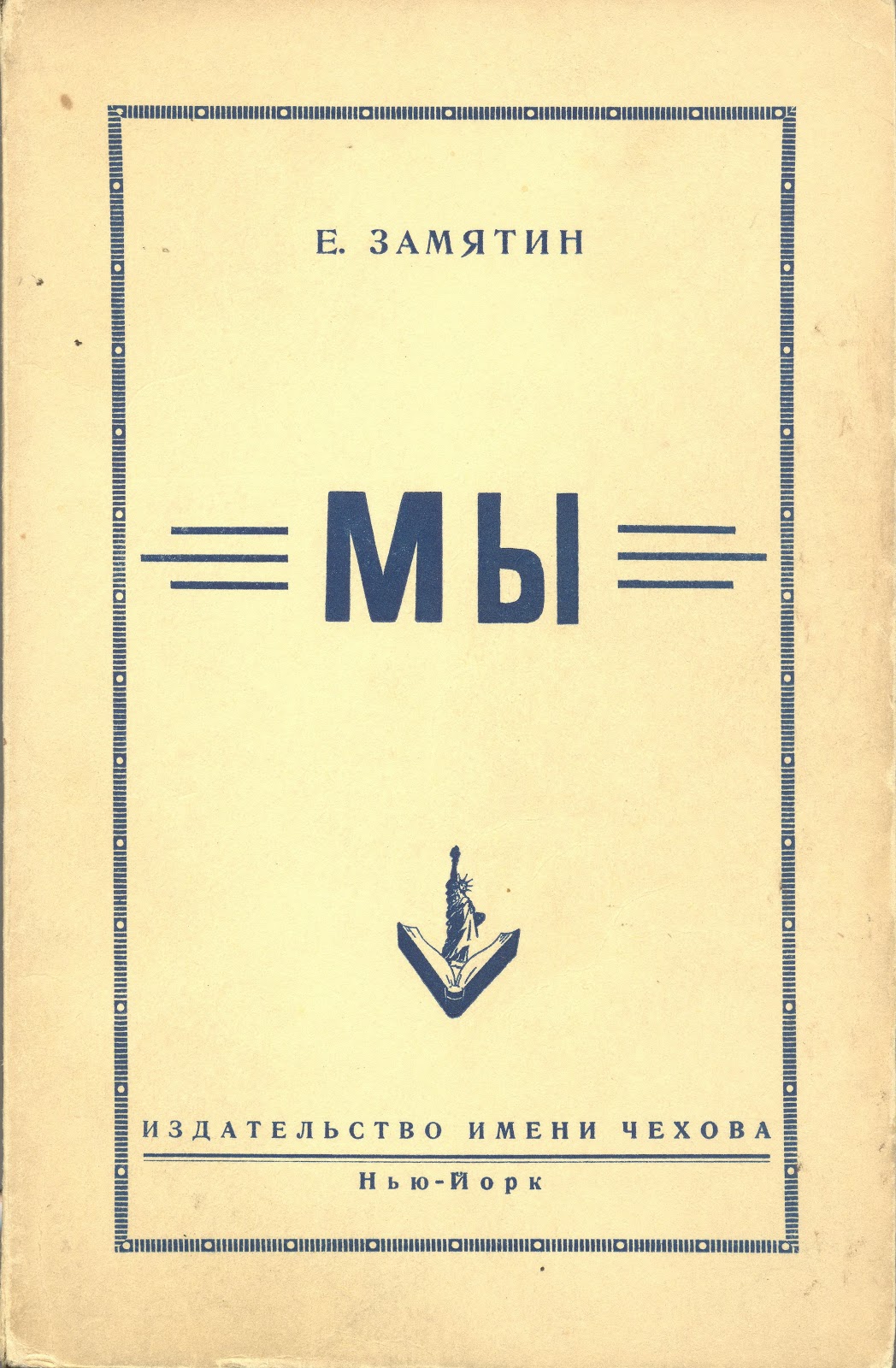

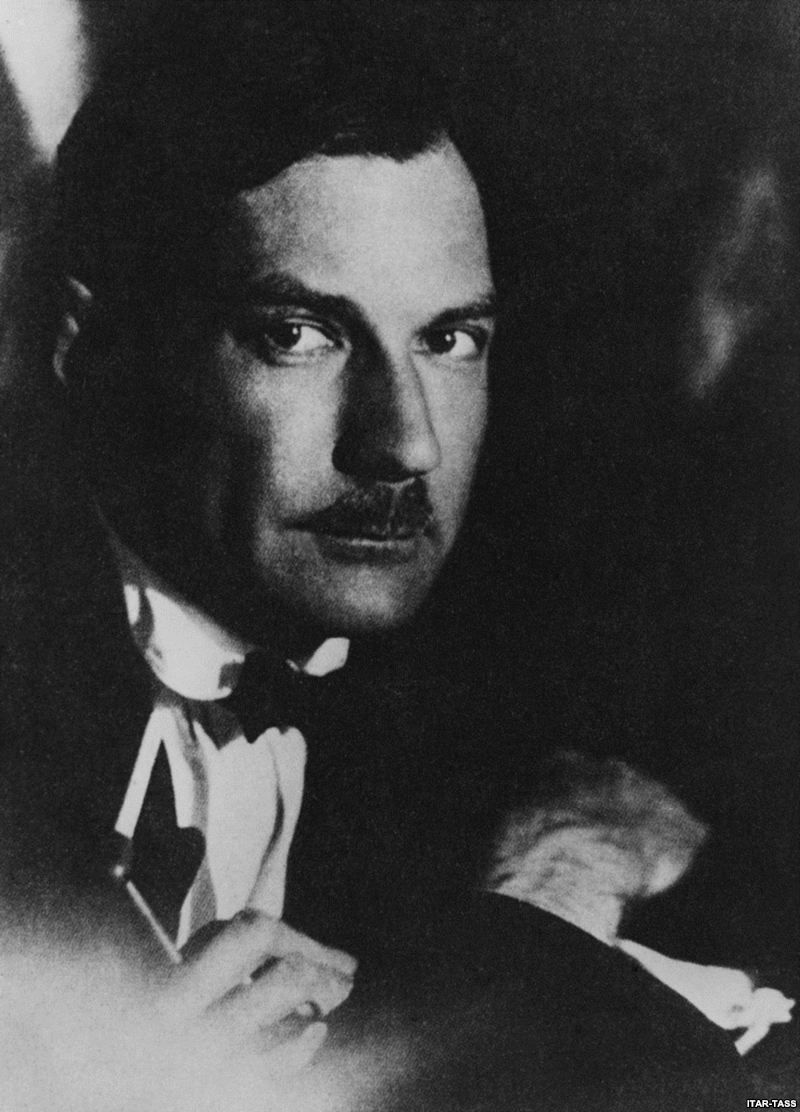

We by Yevgeny Zamyatin written in 1921 and first published in English in 1924 in New York, is still very much forbidden in USSR. The original Russian edition only came out in 1952 and, again, only in New York.

Having read the book, I can certainly see why.

The story is set far in the future, at least a thousand years or more, with the world having been conquered by a so called United State. As the name implies, there are no other countries or nations, though that might be attributed to the fact that a war wiped out more than 99% of the planet’s population several centuries earlier.

Curiously enough, though perhaps not unexpectedly at all, the war was fought over food and resulted in the creation of a petroleum-based substance that took its place on the people’s plates. The more conventional meals were slowly forgotten.

The nation, meanwhile, is governed by a single person, called the Well-Doer, who is overly fond of mass surveillance and standardizing his subjects. Names have been replaced by given numbers. People live in glass, completely transparent, apartments, and cannot draw down the curtains unless they have, ah, received the pink permission slip. Yes, it means exactly what you think it means.

When they go to sleep, they no longer dream, as dreaming is an illness and has been cured long ago. At breakfast, they chew exactly 50 times per each bite. On the streets, they move as one, marching in lines, wearing the same uniforms. Confusing emotions and imagination gave way to logic and reason. To formulae, equations, and science. There is no freedom. The people are happy.

They are also planning to build a space rocket (with the appropriate mathematical name, "The Integral") to share their way of life with any extraterrestrial life forms they might encounter.

The story follows one of the lead builders working on the rocket. A model citizen, D-503, decides to start a journal, depicting his daily life and thoughts, and then put it onto the rocket. Enlighten the aliens, so to speak.

I will let you, dear readers, read for yourself exactly what we learn through each of D-503’s entries, but suffice it to say, action, drama, and (really, really awkward) romance abound. As well as, at times, rather confused ramblings of a man who has never before been confronted with illogical feelings.

Naturally, I read the novel in Russian. However, I did take time to peruse the 1924 English translation as well. On its own, it seems to be a fairly good read, but I’m afraid it falls somewhat short of the source. In the Russian We the writing is uneven, full of short bursts and ragged edges, that seem to be smoothed or faded when one opens up the English copy. And I’m not talking about the length of the sentences, but rather the structure and choice of words. Still, that slight demerit only really matters if one makes it a point to compare the two versions. If you have the chance (and ability) read it in Russian. Otherwise, the English copy will serve perfectly well.

The style of prose itself is very much in tune with the character, never straying too far from what we might expect, and yet delivering a gripping account of D-503’s deconstruction of his own world. The contrast between the mathematical precision of some parts and emotional upheavals of the others works nicely to highlight the faults of the world Zamyatin built.

Despite the bleakness and sheer uniformness of the United State, the characters we meet throughout the novel are vibrant and very much alive. Every single one of them has something to say, and every single one of them is worth listening to. The characters are the novel’s strongest side, and after finishing the book, I caught myself wanting to know what happens to them next.

In fact, the characters have quite possibly outshone any and all possible allusions to USSR and its problems for me. The satire and criticisms are plain, don’t get me wrong, but considering that Zamyatin wrote the book when the Soviet Union was only in its infancy, the impression they left with me is not quite as deep as one might expect.

I greatly enjoyed We, for all its dystopian gloominess. This is a book that has now become a permanent fixture on my bookshelves and I foresee many rereads in its future. And so, dear readers, I invite you to try it out for yourselves. I promise it will not disappoint.

I give “We” by Yevgeny Zamyatin five integrals out of five.

I read this many, many years ago. I don't remember much of it, but I do recall enjoying it (in translation). It may not be well known, but it inspired Orwell and Nabokov, and probably Rand as well. Huxley swears he didn't hear of it until after he wrote Brave New World, but Orwell didn't believe him, nor does Vonnegut. I don't know if you can call it the Ur-dystopia (to use a fairly new term), but it certainly influenced the modern interpretation of the concept.

I have also read this in English translation and enjoyed it. It does indeed seem to be very similar to Ayn Rand's "Anthem," but with more wit and imagination.