by Arturo Serrano

When I was appointed, in recent weeks, as a cultural attaché of the Colombian embassy in Bonn, I was beside myself with excitement about the prospect of imbibing from the richness of Teutonic civilization, whose light was but briefly obscured during the war. I say this without intending in any manner to dismiss the graveness of the evil that merely one generation ago seared Europe, but not even an army of murderers can outweigh the numberless German generations possessed of extraordinary creativity that preceded them. With one glance at the poetry of Vogelweide or Eschenbach, one gives perpetual thanks for having studied the German tongue. And the pleasures aren't limited to the written word: I need only give two cardinal points, Bach and Strauss, and the mind delights in the long chain of beauty that extends between them. This is the proud nation that birthed Dürer, Gutenberg, Leibniz, Schiller, Humboldt, and that titan among titans, Goethe… And look at the Germany of today! Upon leaving the airplane, I nearly fainted as I realized I was setting foot on the land of Günter Grass, of Siegfried Lenz, of Heinrich Böll! I believe I could put you all to sleep reciting names long before I'm finished praising the inexhaustible wellspring of genius that is Germany.

Alas, the Fates judged it fit to make a mockery of my elation when it came time for me to experience my first taste of German culture in an official capacity as a foreign diplomat.

It happened at the end of April in downtown Bonn, at the exquisite Art Déco building of the Metropol Theater, which faces the square where a public market has been in operation since the Middle Ages. Therein it was my duty to endure the projection of what promised to be an instructional documentary film with the inviting title Memories of the Future. The torrent of laughable inanity I had to sit through brought me a blunt reminder that, alongside its luminaries, German-speaking culture has also produced its unenviable share of ignorance. And sometimes it's the sort of ignorance that can kill: remember the Doctors Gall and Spurzheim, from whom the Nazis learned the odious art of cataloguing skull proportions. Or that close friend of Freud's, Doctor Fliess, who pretended to cure depression by butchering the inside of the human nose. Or that abominable quack, Doctor Morell, whose greatest blunder was that his pills of strychnine and belladonna didn't kill the Führer fast enough.

This civilization has had to suffer under the various teachings of men who weren't even physicians, such as Pastor Felke, who claimed to be able to diagnose by staring at people's eyes; or Father Kneipp, whose recommended cure was to walk barefoot in the snow; or Mr. Just, who wanted to replace all chemical medications with compresses of wet clay. And of course, from Germany also come those twin emperors of medical nonsense: mesmerism and homeopathy. Moreover, this ignorance has been exported to the world: in America, Doctor Gerson's treatment for cancer was to pump coffee, castor oil and oxygenated water into the patient's rectum, while Doctor Lust prescribed eight-hour-long hot showers to treat all diseases. Still in today's Germany, the ineffably dangerous Doctor Nieper continues to teach that living in an area with a subterranean water current causes cancer. It's clear that the fecundity of mind of German-speaking culture doesn't exclusively lean towards truth.

This time, the field over which that long tradition of stubborn unlearnedness dares to cast its dim gaze is archaeology. The documentary Memories of the Future is a printed-word-to-moving-image adaptation of a book with the same title, published two years ago by notorious Swiss charlatan Erich von Däniken, whose peculiar ideas about human history bear a strong resemblance to those of notorious Italian charlatan Peter Kolosimo (an intellectual heir of notorious Russian charlatan Immanuel Velikovsky), and may have been inspired by the writings of notorious French charlatan Robert Charroux and notorious British charlatan W. Raymond Drake, or perhaps the earlier notorious British charlatan Harold T. Wilkins, who learned much from the notorious Russian charlatan Helena Blavatsky. Clearly an illustrious lineage.

Däniken's claim to fame hitherto, Der Spiegel tells me, was a series of financial crimes for which he was sentenced to three years and a half of prison last February. He's no stranger to incarceration: in the preceding decade he already spent nine months behind bars for similar misdeeds, and my diplomatic peers in Switzerland have managed to unearth court records that tell of a previous conviction for theft in his youth. It's thanks to the money he obtained illicitly by submitting false documents to credit banks that he was able to pay for the extensive travels around the globe that he proudly mentions in both the book and the film.

In those travels, he supposedly collected numerous proofs that spaceships from the stars visited our ancestors in prehistoric times, and therefore all the mythologies and all the architectural wonders from the past are actually half-remembered testimonies from such contacts. As befits a proven con artist, the material presented in Memories of the Future is a smörgåsbord of unsubstantiated allegations that insult the intelligence of not only its audience, but of ancient humankind as well. Reducing all varieties of traditional religiosity to a cargo cult, Däniken argues that aliens who landed on Earth before recorded history are the origin of the ubiquitous stories about wise gods who descended from heaven and taught mortals agriculture and other crafts. He even goes a step further and identifies those unknown astronauts as our true ancestors.

It's hard to find a logical order in which to enumerate the colorful "discoveries" cited by Däniken. A possible starting point is his reinterpretation of some miraculous episodes in the Bible as better explained by the operation of advanced technology. Where the prophet Ezekiel records a vision of God sitting on his celestial throne, amid thundering clouds of fire, Däniken takes the description to correspond to a rocket. Where the prophet Elijah ascends to heaven in a whirlwind, Däniken would have it reflect an alien abduction. Where we read that death promptly befell anyone who accidentally touched the Ark of the Covenant, he views it as evidence that it contained a portable nuclear reactor. Where we read that the first woman was created from the first man's rib, he reads it as a laboratory report of a successful cloning. Where the Flood myth mentions celestial beings having offspring with mortals, he sees alien-human hybrids. He even makes the disturbing suggestion that Sodom and Gomorrah perished in the same manner of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Other pieces of holy scripture are also subjected to his creative misreading: in the Mahābhārata, the gods often ride floating chariots, which sometimes seem to be more like full palaces above the clouds; just as he did with the book of Ezekiel, Däniken wants to read in those passages sightings of interstellar vehicles. And in the epic of Gilgamesh, where Enkidu has a dream in which he's taken to the realm of spirits, Däniken claims it's actually a flight that reached orbit altitude.

No doubt aware of the reaction such statements must elicit among people better educated than him, Däniken predictably plays the Galileo card and brings up the case of Heinrich Schliemann, the self-taught explorer who, by meticulously following the clues in the Iliad, found the buried site of Troy, despite how much his contemporaries ridiculed his quest. The comparison, however, doesn't hold. Schliemann took a fanciful tale and sought the layer of earthly reality hidden in it. What Däniken tries to do instead is to salvage what they contain of fanciful. The only regard in which Schliemann can be said to mirror Däniken is his embarrassing inexperience when it came to correct archaeological procedure; Schliemann's clumsy digging method destroyed much of what he was hoping to find—and whatever relics he did find he smuggled out of Troy under the nose of the Ottoman government. Perhaps Däniken reveals more about his research ethics than he intends when he names Schliemann as his precursor.

The same knee-jerk mode of analysis he applies to texts is employed with the visual arts. Portions of Medieval paintings that most likely represent comets or angels are invariably compared to space capsules. He shows old maps that include a continent around the South Pole to defend his argument that some form of aerial observation must have occurred, ignoring the fact that a Terra Australis had been imagined to exist since classical times for purely philosophical reasons, and its immensely variable depiction in those maps doesn't follow Antarctica's actual coastline. Nonetheless, Däniken imagines that the discrepancy in shape is due to the artist's point of view being located at orbit altitude above Cairo.

Indeed, because the schools of charlatanism apparently must converge, it comes as no surprise that Memories of the Future joins the legions of fraudsters who have invented wild tales about Egypt. In the rhetorical equivalent of pointing at the pyramids and dropping his jaw, Däniken expresses disbelief that human hands could have raised such gigantic monuments. (Also, on the basis of no evidence, he proposes that mummification developed as a failed attempt to copy an alien technique of body preservation.)

The same argument is made about other famous works of antiquity: Too big! Too heavy! Too tough to carve! Too unwieldy to transport! Too skillfully put together! Instead of foundations for temples, those terraces must have served as launching pads for rockets! In prehistoric rock carvings found in the Sahara, whose rather inexpert resemblance to the human shape is attributable to the difficulty of working the material, Däniken sees astronaut suits and helmets (the more prosaic possibility of those rounded heads being representations of ceremonial masks doesn't occur to him); and where we see geometric patterns whose original meaning has been lost to time, he identifies designs for spaceships, or circuit boards. Figures in horizontal position are assumed to be floating in vacuum when they could simply be swimming (the Sahara is known to have been much more fertile some millennia ago).

Däniken's flat rejection of mundane explanations extends to wherever some culture boasted any intellectual progress. Thus, the impressively accurate calendars of Mesoamerica must have been learned from aliens, and the 10th-century stone observatory at Chichén Itzá must have been based on a more advanced blueprint. Not only our ancestors, but Mother Nature herself is denied her creativity: the flooded sinkholes where ancient Mesoamericans performed sacrifices, called cenotes in Spanish, strike Däniken as too perfectly rounded to have a natural origin, but any geologist could have dispelled his misconception. They are, in fact, natural.

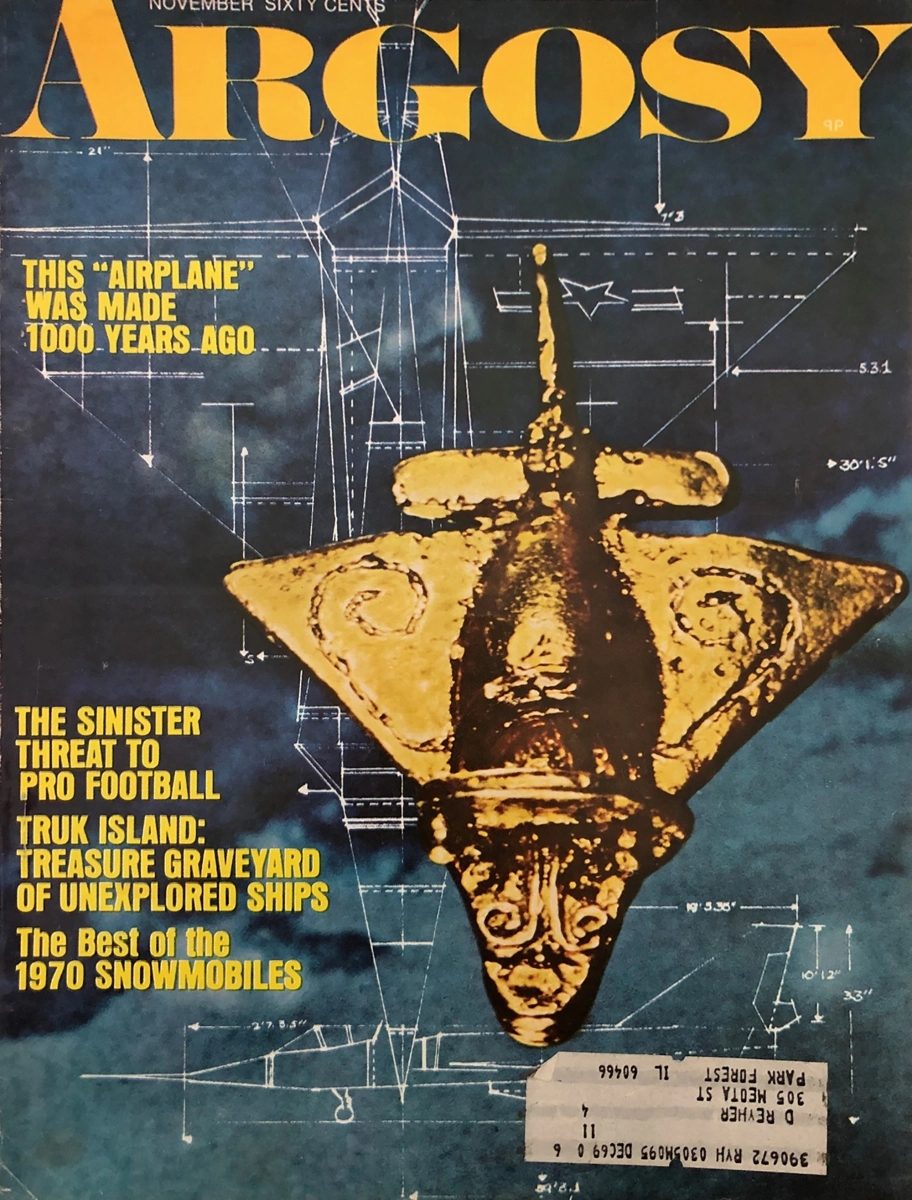

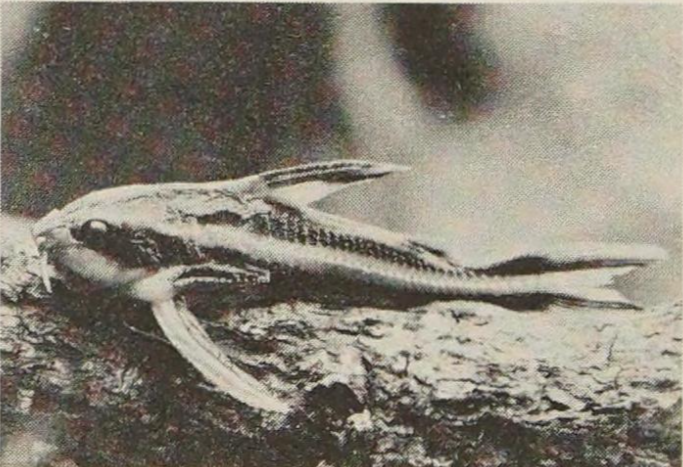

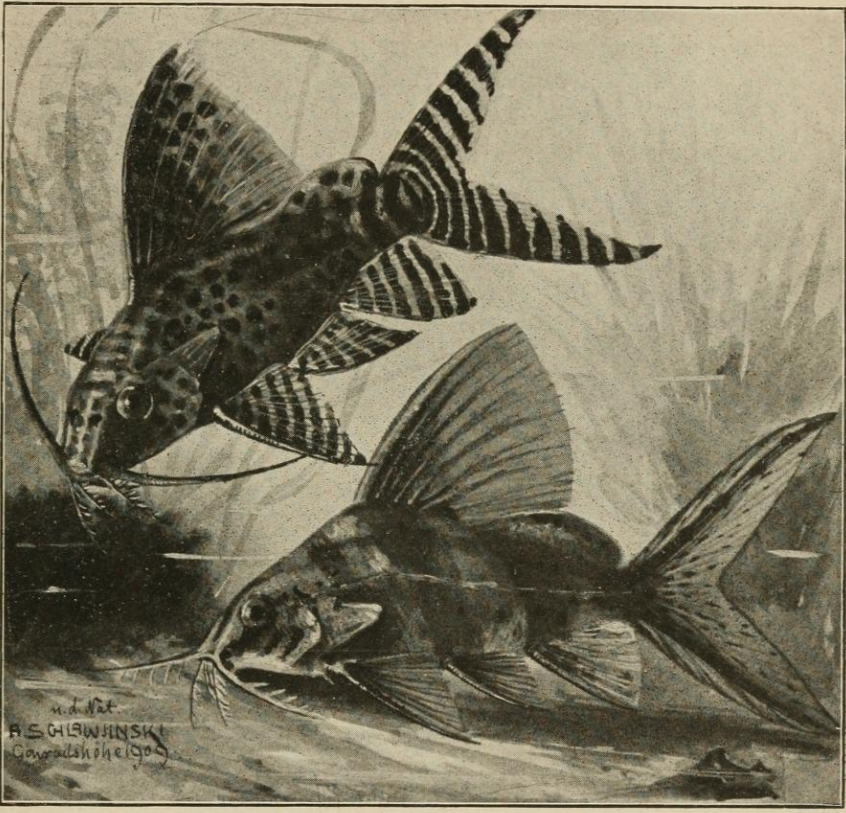

After showing us another round of assorted artwork from around the world, whose curious faces and attire all make Däniken think of astronauts, because the concept of figurative expressiveness is (pardon me) alien to him, he takes us to a point in the film that irked me personally. Here are the background details: in 1954, the Colombian government sent some fish-shaped statuettes of Indigenous origin to be displayed in American museums. Some reproductions commissioned by the museums came to the attention of notorious British charlatan Ivan T. Sanderson, monster hunter and disciple of notorious American charlatan Charles Fort. It was Sanderson who first put forward the theory that those figurines, crafted in a gold-copper alloy a thousand years ago, didn't represent fish, but airplanes. His argument rests on the convenient observations that the types of airplanes he identifies look exactly like those being manufactured in this moment of the 20th century, and that he is unaware of any fish species that could correspond to their shapes. That is how the Colombian "ancient airplanes" entered the realm of pseudoscience and ended up noticed by Däniken.

Setting aside for a moment the known fact that chimeric combinations of different animals are frequent in our Native art, the claim that those pieces don't represent any known fish is easy to make when you've never met Colombian fauna. But Sanderson doesn't have that excuse. If he had bothered to visit a library in his own country, he could have encountered the Illustrated Dictionary of Tropical Fishes, an English translation made by Viggo Schultz from the original German text by Hans Frey.

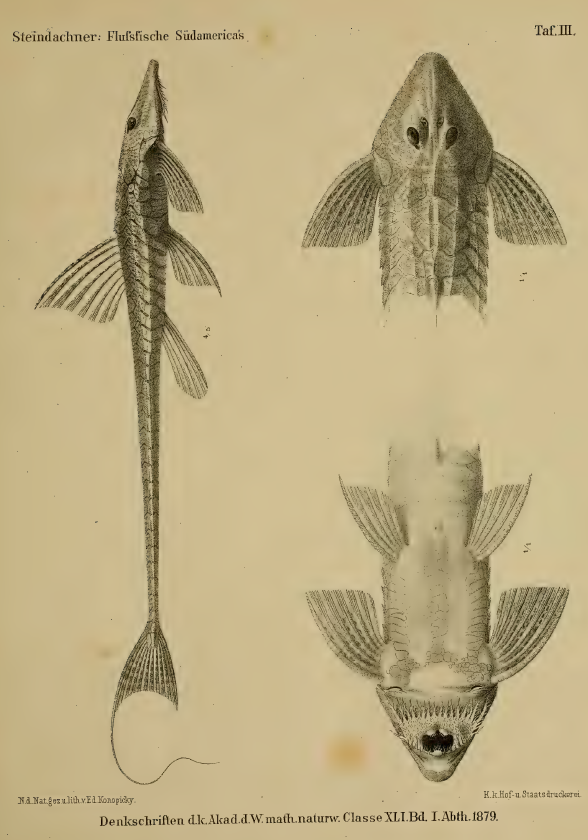

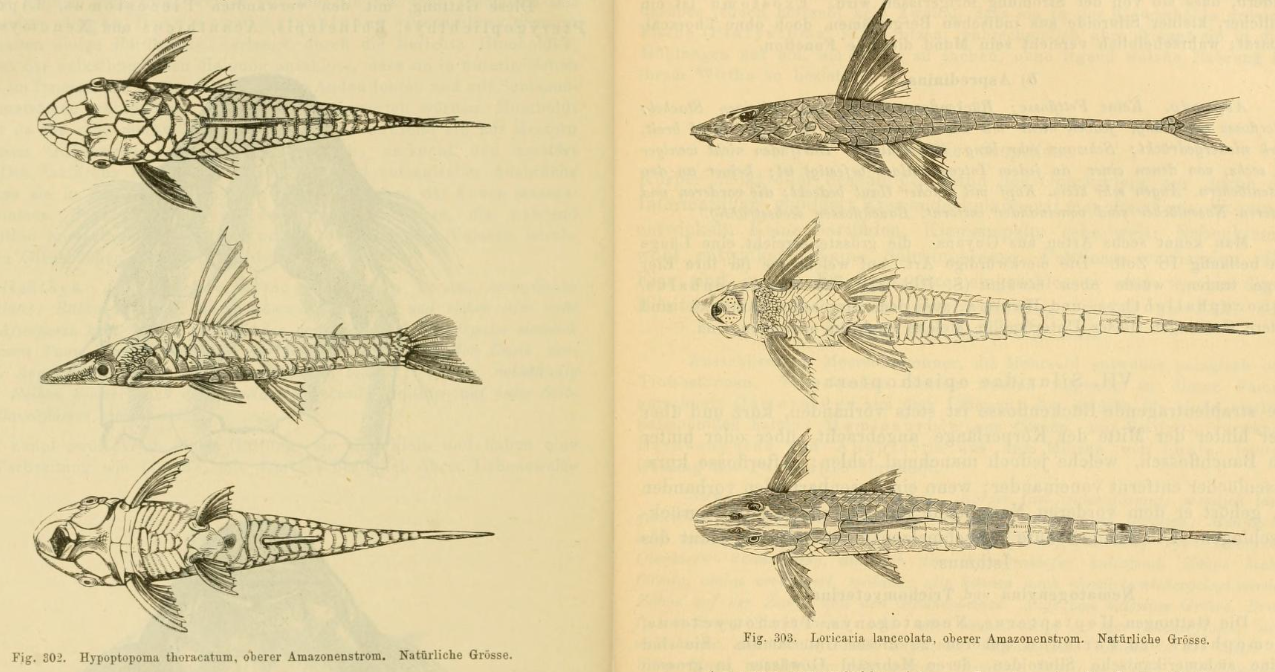

Däniken, too, is without excuse, because our fishes have been discussed in his language for over a century. At the libraries available to him across the German-speaking parts of Europe, he could have consulted a number of helpful volumes, such as K. Stansch's Exotic Ornamental Fish in Words and Pictures, Franz Steindachner's Contribution to the Knowledge on South American River Fish, and Albert Günther's Manual of Ichthyology.

Far from aircraft, they're types of freshwater catfish. Their flattened faces and down-facing mouths are useful for eating detritus from river bottoms. Members of that family are well known to Colombians; we call them bagres. They're tasty. But for Däniken it's more beneficial to stick to the intellectual laziness that lets him sell thousands of book copies and movie tickets by misrepresenting my country's cultural heritage.

The lies shamelessly told in Memories of the Future didn't emerge fully formed, like Pallas Athena, from Däniken's head. They exist as part of a well-established current of unenlightened speculation. From the list of charlatans I provided above, at least Charroux and Wilkins are known for certain to have voiced openly racist sentiments. Part of the purpose of crediting extraterrestrials for the wonders of our past is to minimize the very human achievements of premodern peoples. As it happens, the publisher that printed Däniken's book had its entire text revised by editor Wilhelm Roggersdorf, who used to work for the Nazi newspaper Völkischer Beobachter. If you pay attention, you can catch each of the quick fragments in Memories of the Future where the narration casually mentions that the divine visitors from the stars, and by implication the original humans, were white-skinned. You'll find no serious paleoanthropologist or evolutionary biologist who agrees with that assertion. Were it not for the irresponsible effect of misleading the public as to the facts of human history, Memories of the Future could be waved aside as a silly entry in the science fiction genre. Its mortal sin is that it labels itself as nonfiction, and thus its stated goal is not to amuse but to teach. I'm still not very acquainted with European education systems, but I hope that they are competent enough to inoculate the masses against these perverse fabrications.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

Glad to hear you're in Bonn and overall enjoying your experience, though us West Germans have a somewhat troubled relationship to the fact that this Rhenish small town is now our capital. Anyway, if you ever come up north, feel free to visit me. I also hope to see you at this year's Worldcon in Heidelberg.

My Mom and my aunt are both members of the Bertelsmann Book Club, which has been heavily pushing von Däniken's books, so I have been exposed to his brand of nonsense, pilfered from various SF novels, before and could happily skip the movie. Though it's a pity to see how far down director Harald Reinl, who used to helm wildly successful Edgar Wallace and Karl May adaptations only a few years ago, has come in the world. West German cinema is in trouble, but I didn't think the situation was that bad.

Von Däniken is actually languishing in a Swiss prison at the moment – not for peddling nonsense, but for tax evasion in connection with the luxury hotel in Davos that he manages.