And yet our June Galactoscope continues! We have a work by a brand new novelist (though the author is no longer new to the SFnal scene), an exciting novel by a vanguard of the New Wave, and the return of two familiar but still fresh writers. Science fiction truly is a young man's game this month!

by Amber Dubin

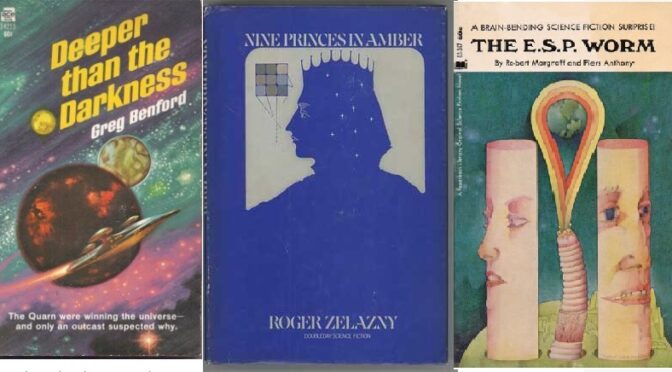

Deeper than Darkness, by Greg Benford

I have to be fair to Greg Benford and his work and acknowledge the fact that I’m most likely the opposite of the target audience for his first novel, “Deeper than Darkness.” Unfortunately for him, I did read his book and my personal biases made the experience incredibly painful.

Cover by Kelly Freas

I reached into this grab-bag hopeful, as the world Greg delicately builds feels very Star Trek-inspired: a space-faring Earth race has reached far enough into the void that they have successfully forged alliances with at least two alien races outside of themselves before reaching the first diplomatic obstacle in the Quarn (much like the Federation when they encounter the Klingons or the Romulans). I first began to bristle when Benford began laying out racially-charged themes in setting up the protagonist’s description. In this case, they make a point to say that he is half-caucasian, son of one of the last “pure-blooded Americans” (don’t even get me started) which makes him an outcast in a world where the only races left in mankind are Asian and Indian. Though I tried to suspend my revulsion, knowing that even the Federation had a difficult past with their Eugenics Wars of the 1990s, this is where I ultimately realized that I am not Benford’s target audience, an audience clearly meant to be sympathetic to a story making a white man the ‘true oppressed people.’

From the very point that Benford introduces our hero Ling Sanjen, we are made to know that though he is a high-ranking fleet officer, he would be even higher in rank if not for anti-white discrimination which is given its own racial slur equivalent to a modern term starting with an ‘n’ (that the author is clearly more comfortable writing out than I am). I suspect that this middle-aged, mid-life crisis suffering character is meant to be a wish-fulfillment character–I am tempted to surmise that Benford, himself, must have once gone to an Asian country and been treated like less than a member of his inherently superior race. I say this because as the protagonist is consistently doing an exemplary job in command of all these shifty Asian underlings with “simian eyes,” but his authority is consistently undermined unfairly due to him being the only one with his skin color.

This issue comes to a head when he is assigned to investigate the devastation after a Quarn attack on an outpost and he makes an insightful conclusion that his ship was being used as a vector to carry an agent of biological warfare back to the home planet in the form of the outpost survivors. Tonji, his ambitious second in command, disagrees with this conclusion and mutinies to overthrow Ling’s decision to quarantine the survivors and delay return to Earth with them. As the Empire never liked someone with Ling’s white skin being in such a powerful position in the first place, they take Asian Tonji’s side and the survivors are brought back to earth, unleashing a hellish plague on humanity that causes its members to self-isolate and lapse into fatal bouts of insanity.

It is at this point in the story where I truly began to struggle to finish the second half, because it is here we are introduced to the protagonist’s (and quite obviously the author’s) naked misogyny. One of the biggest consequences to Sanjen’s failure to protect earth from an alien illness should have been that he and his wife and two children also fall ill with the disease. Sanjen makes a full recovery, as his genetic diversity gives him an edge over his Asian wife and children, who must have been “weak.” I was genuinely appalled at the character’s near psychotic detachment to the loss of his entire family, which we are assured is acceptable because his kids were whiny and his wife had begun developing tension lines which he lamented because “she used to be pretty, once.” There is an almost acceptable explanation to this cold behavior when we find out that middle aged for Sanjen is 117 years old, which implies that a certain level of sociopathy could be normalized in a society where a man’s vitality lasts so long that he begins seeing marriage and families as disposable.

My personal biases at this point were clearly getting in the way of having an enjoyable experience with this book because I usually root for protagonists with a modicum of human decency and Benford did not provide me this for the rest of his novel. Showing no guilt, remorse, or sadness, Sanjen leaves his still-dying family on a now rotting planet to gallivant off to a new assignment on a New Delhi planet. There was a briefly terrifying moment where he thought this planet might contain a negro but thankfully we were saved this possibility as “they were all killed off in the Riot Wars” and the crewman in question was just a darker skinned Indian man. It is also very obvious how much of a self-indulgent fantasy this book is: though Sanjen is supposed to be focused on fighting off an increasingly successful alien invasion affecting the entirety of the human empire, he yet finds plenty of time to sleep with every beautiful woman he lays eyes on, which we’re supposed to fully endorse because he already has trouble even remembering his wife’s name (in fact, he never bothers finding out if she’s deceased or not).

The audience is clearly supposed to pay attention to the themes of Asian communism and spirituality being a flawed system to unite humanity because it leaves society vulnerable to attack by a more ruthless individualized capitalistic society and blah blah blah but I could not help but be distracted by the author’s many character descriptions. Every room was either filled with powerful men whose trustworthiness was determined by their proximity to whiteness or women that were either playful, submissive, flirtatious waifs, or abrasive, unlikable harpies. Benford spent so much time on these descriptions, dispersed amongst un-thrilling action and rather clunkily choreographed fight scenes that I found myself not even caring when Sanjen’s belief in his racial superiority becomes his undoing as the story crashes to a rather rickety and dissatisfying conclusion. My interest in the political intrigue tended to fall to the wayside for me when the protagonist made a point to intersperse his important meetings with lascivious romps with his new plaything whose nipples he found “simply fetching.”

I couldn’t justify the lowest score because the alien invasion/war was an interesting premise and if all the racism and sexism had been taken out, this could have been a decent book, but unfortunately that would be cutting out at least half of its content.

Two stars.

by Joe Reid

Nine Princes in Amber, by Roger Zelazny

“The proof is in the pudding is in the eating.”

Anyone who spends more time reading than staring at the television, including this brother, can tell you the truth of that epigram. You really have to taste this story to know how good it is. Nine Princes in Amber delivers to your literary palate the right flavors at the right times, ensuring a satisfying multi-course meal. I both found it filling and yet was still left with a desire for more.

Cover by Amelia S. Edwards

This story had one of the best openings I’ve encountered in a while. It begins by following Corwin, a man with amnesia, who starts his journey in the same place we, the readers, often find ourselves literarily: unsure of who he is or what’s happening. We meet other characters like Fiona and Random, who clearly know Corwin, have some relationship with him, but may not be trustworthy. Soon, we learn they’re his siblings, two of many. The more Corwin finds out about them and the world they inhabit, the more the reader learns.

This narrative device, Corwin knowing nothing, serves to start the off story well. It feels like a grounded detective tale, but gradually transitions into something more fantastical, historical, futuristic, and even alien. Big leaps can be taken, because the fact that we don’t know the world allows for anything to be possible. During an intense journey with Random through strange lands, Corwin has a violent encounter with Julian, another sibling, after Corwin behaves in a way that Julian finds strange. Up until this point using amnesia as a storytelling tool created a smooth on-ramp into this complex world. Had Corwin been introduced fully formed from the start, I doubt the reader would have cared as deeply. The gradual revelation of Amber, the homeland of Corwin and his family, is a kindness–both to the story and the audience–eschewing the more traditional and clunky expositional style.

But once the amnesia serves its purpose, and we learn enough about Corwin's world, the book then shifts. Corwin’s missing memories are returned. I liken it to adding a rich spice slowly to a dish: too much, too fast, and you overwhelm the senses. Slowly mixing in that ingredient allows for a more subtle introduction of something different. Something that tastes just right.

With Corwin’s memories restored, the book expands its world dramatically. We now see him as a prince of Amber, a kingdom of unimaginable importance, where something has clearly gone awry. This ushers in the second course of our meal.

Once aware of the conflict among the royal siblings, Corwin begins to assert himself. Zelazny opens the floodgates of imagination, as if he hasn’t already done so. We learn of Amber’s significance, its place in the universe, and the mechanics of shadow worlds. Corwin shifts from cautious to commanding. It’s like discovering that a medium-bodied red wine pairs perfectly with roasted chicken; you didn’t know it to be true until you tried it.

Now knowing his purpose–to stop his brother Eric from taking the throne–Corwin sets off to do the impossible. With a handful of allies and a heart full of resolve, he launches a rebellion. It fails spectacularly. Corwin is defeated, humiliated, tortured, and left a broken shell of the man he once was.

But like the unexpected joy of dessert after a heavy meal, the story offers a few surprises. Corwin’s fortunes change so quickly and drastically that even he can scarcely believe it. From start to finish, I found this novel to be a cut above the rest. It introduces its world beautifully and transports the reader to places they never imagined. It does so without becoming predictable or boring.

It is, however, not perfect. The story tends to introduce characters, like Deirdre, a possible love interest for Corwin, who seem important but are never seen again. It is also clear that we have been left on a cliff-hanger (appropriate given that much of the action takes place on a cliff-side). That aside, it remained a deeply satisfying read. A bold, flavorful dish of a book that leaves you satiated, but desiring the next course. Nine Princes in Amber must be tasted to be fully appreciated. You won’t regret it.

Four stars

by Tonya R. Moore

The E.S.P Worm, by Piers Anthony and Robert E. Margroff

Piers Anthony is a rising star lauded for works such as Chthon and Macroscope. His counterpart, Robert E. Margroff (with whom he previously wrote The Ring) is more prolific as an essayist and short story writer. Margroff’s individual works include a number of short stories, Monster Tracks from 1964 being the first. Despite both authors having been around for a while, The E.S.P Worm was my first encounter with either author's work.

Herbert Norton Rogoff

This exciting story centers around Harold Prodkins, a man who obtained a high paying, made-up job as Minister of Intergalactic World affairs, through nepotism. He gets a wake up call when a slimy, worm-like alien somehow winds up on Earth and for once in his privileged life, he has to do some actual work.

He teams up with one Dr. Dilsmore, a beautiful and (purportedly) sensual, woman scientist who has already been in communication with the alien. They then interview the alien together. It turns out this telepathic being, named Qumax, is a precocious and criminally unprincipled juvenile on the run from his own father, a being with enough power and influence to destroy planet Earth on a whim.

The trio escapes along with Qumax’s human guard, Nitti–-which makes little sense because for some reason I never quite ascertained, except perhaps, xenophobia, Nitti was determined to kill the alien child at one point. They take to the stars with the intention of helping Qumax find his way home. Qumax and company then proceed to wreak havoc across the universe.

This interstellar adventure, spanning more than a decade, would have been, could have been one of the best stories I’ve read in quite some time. The story is almost brilliant and the humor therein a well-aimed dart that unfortunately for other reasons misses its mark because entertainment value aside, The E.S.P. Worm rankles in more ways than one.

First, for someone who routinely discounts women, the protagonist, Harold Prodkins, spends an awful lot of time thinking about his female counterpart’s clothing and anatomy. His preoccupation with sex and the opposite sex–-while the fates of millions hang in the balance–-is ludicrous. His manner of casually relegating the institutionalized oppression of women as nothing more than a great inconvenience to the male libido is confounding and perturbing.

The story further takes a troubling turn. During their travels, Qumax and company encounter an alien faction that offers them the opportunity to enter into a slave contract. The supposition here is that slaves are very well treated and rewarded for their labors by those who presume to own them. It's not that humans were wrong to institute slavery on Earth. They merely went about the practice of people owning people the wrong way.

This particular ideology twists the truth of a barbaric practice and is a thinly veiled attempt to minimize the horrors experienced by the African people. There was nothing laudable or respectable about the transatlantic slave trade. There is nothing acceptable about the ongoing racism and rampant discrimination that black people constantly face even now. Slavery was a brutal and dehumanizing custom where black people were subjected to torturous treatment, humiliated and virtually cannibalized.

Perhaps Mr. Anthony and Mr. Margroff really are ignorant about the realities of slavery on our tiny little planet. Perhaps they don't mean to gloss over the horrors of nearly 400 years of cruelty and the continued oppression of black people. Two modern white men, presumably of intellect, trying to paint an appealing picture of slavery is an affront to black people everywhere. It breaks an inviolate common sense rule. The oppressor should never presume to speak on the lived experience of the oppressed.

The E.S.P. Worm by Piers Anthony and Robert E. Margroff is a well-written book that I really wanted to like. Unfortunately, it disappoints on a fundamental level, and I dare say the authors could have done much better in that regard.

2.5 out of 5 stars

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]