by Arturo Serrano

I've spent the last few months exchanging letters with an American friend, who has been educating me about a curious phenomenon they're seeing over there: the quick emergence of new religions whose foundation is, uniformly, some account of an alleged extraterrestrial encounter. From the peculiar case of the Mormon faith, I already knew that the Americans had a unique ability to cook up a doctrine from whole cloth and make it explosively successful in terms of gaining devotees and social influence. But even that knowledge did not prepare me for the alarming piece of investigative journalism which my friend has mailed me along with his latest letter. It's a book published this year, written by a Dane called George Malko, with the title Scientology: The Now Religion. It describes the author's journey to explore and unravel a whole intricate system of theology, liturgy, morality, and salvation begun only two decades ago, by the obviously troubled science fiction writer of moderate fame, named Lafayette Ronald Hubbard.

In a nutshell, Scientology (a bland, uncreative name if I've ever heard one) teaches that the human spirit has lived countless lives in countless bodies on countless planets, and we all carry the scars of emotional trauma accumulated over aeons of reincarnations. But fear not! The same church that reveals to you that you have this problem happens to be selling the solution: by letting a complete stranger take note of your darkest secrets in front of a lie detector, you can achieve the next level of enlightenment. And the next. And the next. With each milestone, you're supposed to become more in control of yourself, more unperturbed by the psychic echo of your past lives, and more capable of performing feats of paranormal wonder. There's a finely subdivided series of degrees of perfection you can rise to, provided that you can afford the requisite study materials. That's the only penitence that this church expects of you: the thousands upon thousands of dollars that it costs to buy its ever-increasing but, unsurprisingly, never complete form of happiness.

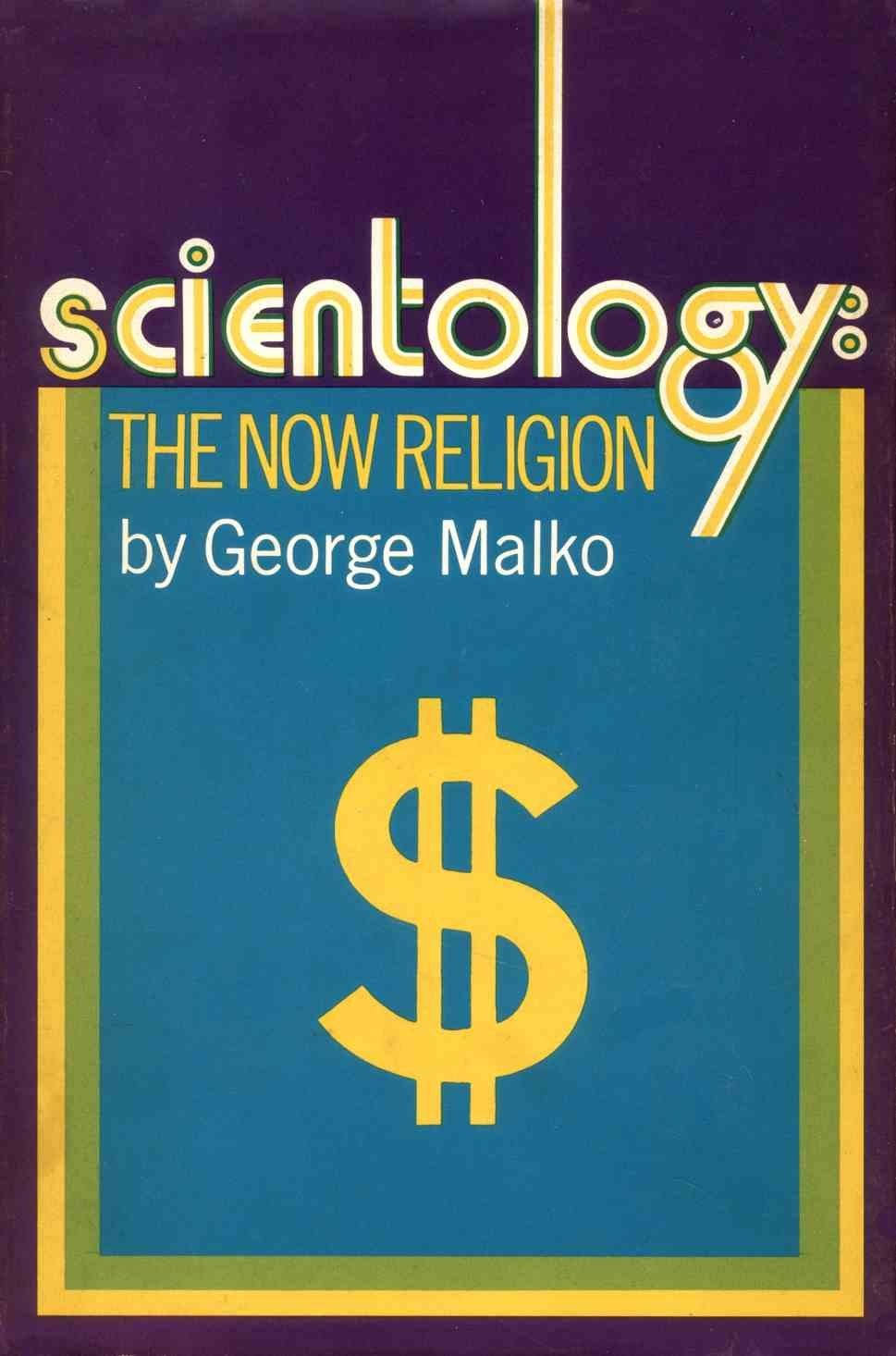

As Malko explains, the ideas that underlie Scientology were first introduced to the world under the similarly nondescript name of dianetics, in an article published in Astounding Science Fiction, dated May 1950. Hubbard was already known to the readers of Astounding for his stories, but this time the then (and current) editor, John W. Campbell Jr., took pains to clarify that this is a different type of text: "I want to assure every reader, most positively and unequivocally, that this article was not a hoax or joke[, but a] direct, clear statement of a totally new scientific thesis."

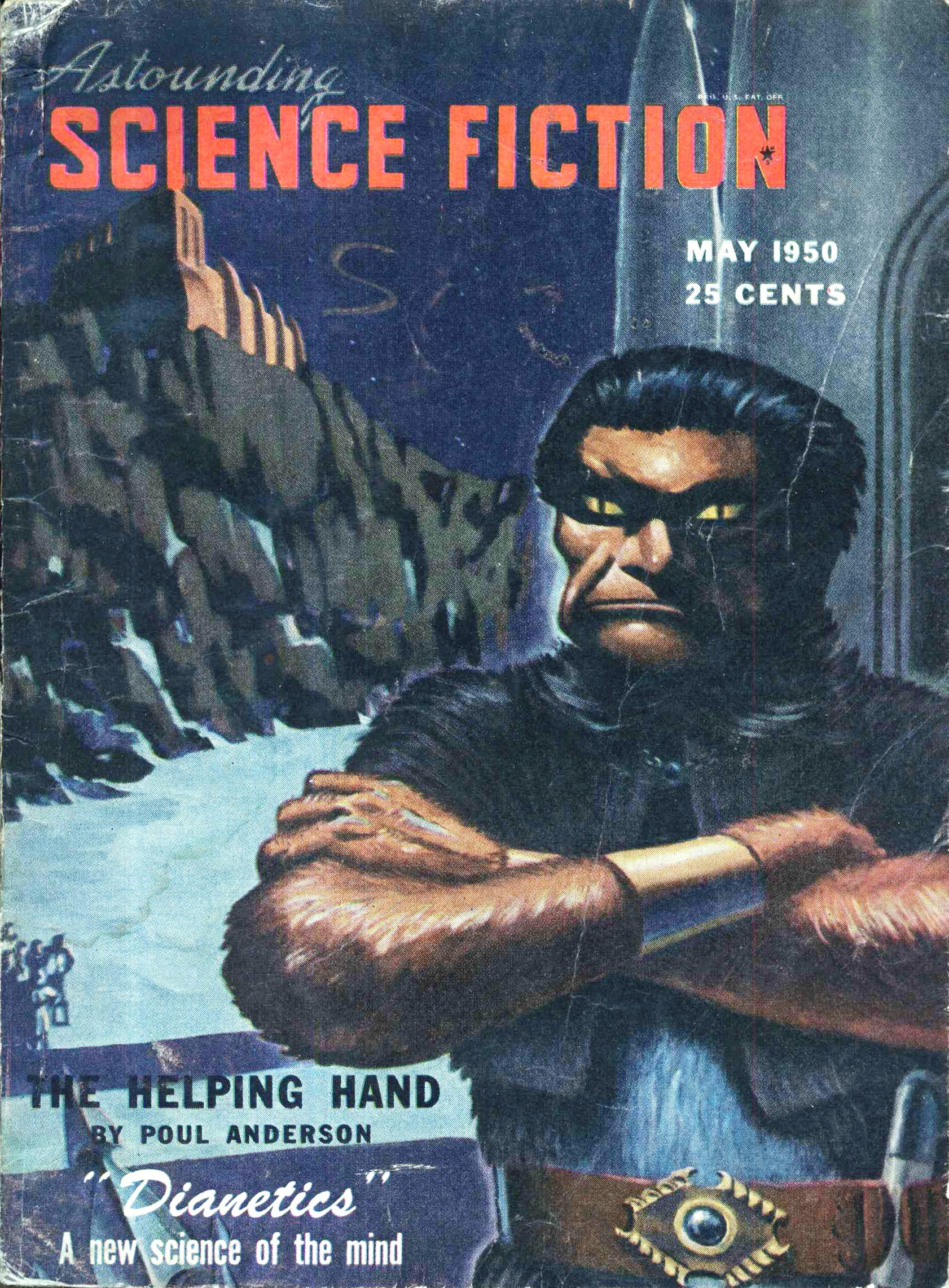

That's right: dianetics didn't present itself as a religion, but as a field of psychology. It claimed to follow from a rigorous examination of the origin and nature of human suffering, even if it admitted to taking inspiration from dozens of mystic traditions. To help lend more respectability to Hubbard's ideas, Campbell Jr. had an actual doctor, Joseph A. Winter, write an introduction. In defense of the article, Campbell Jr. went on to assert: "Hubbard, as an engineer, has tackled the problem of the human mind from the scientific method." And Hubbard himself puts it in these terms: "It was the basic contention that the human mind was a problem in engineering and that all knowledge would surrender to an engineering approach." I think it's pertinent here to point out that Hubbard has never earned an engineering degree or any other type of degree.

The fact that this report on a new science was not published in an academic journal but in an SF magazine should by itself be sufficient indication of how much credence it deserves. Unfortunately, falling for pseudoscientific theories is an old habit of Campbell Jr., who previously gave his support to a design for an aircraft engine that was supposed to fly without reaction and an electrical amplifier of psychic waves. If I were trying to publicize my discoveries in any field of knowledge, I'd be embarrassed to have them printed next to an advertisement with the title, and I'm not kidding you, "How A Space Pilot Fell In Love With The Thoughts Of An Insect."

In that article in Astounding, Hubbard narrated how he investigated many forms of mental treatment, including hypnotism, drugs, automatic writing, and exorcism, and found seeds of truth in each of them, but he was the first to put together the full picture. He took it as an axiom that a healthy human brain ought to never make mistakes, in reasoning or in remembering, and it is only in states of emergency that an automatic circuit in the brain briefly takes over to ensure survival, leaving lasting impressions of emotional shock. These records are not quite memories; Hubbard called them "engrams," and he claimed that the body starts keeping track of them shortly after conception. Over time, these engrams acquire psychosomatic manifestations, which according to Hubbard explains most diseases: "Dianetics sets forth the non-germ theory of disease, embracing, it has been estimated by competent physicians, the cure of some seventy percent of man's pathology."

So, the article went, a patient who unearths those engrams, via a technique akin to hypnosis, becomes free from their lingering effects and becomes "clear." Here we reach a key concept in Hubbard's system: "clear" refers to the human brain restored to perfect capacity. Under this model, a respiratory ailment or a joint inflammation could have been caused by emotional damage inflicted in utero, and Hubbard promises that they will disappear after the patient is guided to the recollection of that initial episode. Not only will this unwanted pain cease, but at the "clear" stage, the patient will gain full control of every bodily function. In describing this process, Hubbard makes, perhaps unwittingly, the damning admission that he has tested this treatment in several patients. Now go back to that paragraph where I said that Hubbard doesn't have a professional degree, let alone a medical license. This will be important soon.

In the same year 1950, Hubbard expanded upon the themes of the article in a full book, titled Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health. Malko quotes extensively from it, showing the degree of the mismatch between dianetics and accepted science, as well as the full size of Hubbard's self-importance. To hear Hubbard describe it, "the creation of dianetics is a milestone for Man comparable to his discovery of fire and superior to his inventions of the wheel and arch." The book enumerates more possible causes of engrams, focusing especially on those that are created before birth. For some reason, Hubbard seems to believe that attempts at self-induced abortion are ubiquitous. He also frequently alludes to domestic violence and infidelity. The resulting explanation for the majority of human diseases would be comical if it didn't ooze this much sexism: "Mama gets hysterical, baby gets an engram. Papa hits Mama, baby gets an engram. Junior bounces on Mama's lap, baby gets an engram […]"

Liberation from engrams, which dianetics conveniently offers for a price, proceeds in steps, each more expensive than the preceding one: "release," "preclear," "clear," and lastly, "operating thetan." That funny word, "thetan," refers to the unimaginably ancient human spirit, which has been reincarnating for trillions of years (the fact that our universe is nowhere near that old doesn't seem to bother Hubbard). At this point the attentive reader may ask: if a "clear" is someone who has finally and irreversibly gotten rid of those pesky engrams, what more could one gain from the higher stages? Malko interviewed several current and former followers of Hubbard, who paint a colorful picture of what an "operating thetan" is believed to be able to do: "Reading people's minds, communicating without verbal sounds, lifting objects at will, the ability to exteriorize and be at any point on the planet […] You could walk into a room and be fully aware of eleven conversations at the same time and walk around and call people by name and contribute to the conversations at the right moment. A tremendous ability to command others […] to destroy an object at will […]"

Malko adds, which probably won't surprise the reader, that the American Psychological Association and the British Medical Association have officially stated that dianetics has no supporting empirical evidence. In fact, medical authorities have launched investigations against Hubbard for claiming to diagnose disease, claiming to treat disease, and teaching others to do the same (he founded a Hubbard College and a Hubbard College Graduate School) without having a medical license. Hubbard has moved his center of operations at least twice to evade legal repercussions; now he commands a fleet of vessels that moves around the world, allegedly to investigate ancient cultures for more nuggets of lost wisdom. The same Dr. Winter who wrote the introduction to the article in Astounding went on to work with Hubbard to do more dianetics research, but grew tired of his less than scientific methods. He broke ties with him and founded his own branch of dianetics. Malko quotes him as saying that he has never personally met a "clear."

A few years later, Hubbard started working on the next development of his system: Scientology. The key step to protect himself from further attention from the law was to formally register Scientology as a religion in 1955. Instead of offering treatment for mental disorders, which in every civilized society is strictly regulated, it would now offer spiritual counseling, which everyone and their dog is free to do. This change of approach would prove useful: at some point, the quasi-hypnosis technique was replaced with a modified lie detector (the "E-Meter") for the task of helping people remember their engrams ("auditing"). In 1963, the FDA seized these lie detectors; a 1967 sentence ordered their destruction, but a 1969 appeal succeeded at having the order reversed for reasons of religious freedom. The official position of the Church of Scientology is worded carefully: "The E-Meter is a valid religious instrument, used in confessionals, and is in no way diagnostic and does not treat."

The church encountered similar problems in Australia. According to Malko's report, Hubbard hoped to convert high-ranking members of the Australian Labor Party and through them take control of the government of Australia; instead, a Board of Inquiry concluded in 1965: "However Hubbard may appear to his devoted followers, the Board can form no other view than that Hubbard is a fraud and Scientology fraudulent." Scientology is currently banned in some Australian states.

Looking back at the US, the church has lost its tax exemption in four states, which could possibly result in a decade's worth of debt in back taxes, while the UK, where Hubbard last moved his world headquarters, now denies student and employee status for visa applications related to Scientology.

The current state of affairs is concerning, to say the least. Malko talked to new members of the church, old members, regional directors, expelled heretics, and people otherwise connected to Hubbard in order to get a complete idea of what kind of man he is and what kind of organization he runs. Information on Hubbard is kept deliberately ambiguous; his status as a revered prophet allows him to rewrite his hagiography to inflate his credentials and his spiritual exploration. What is known is that he produces a copious output of books, each of which adds more details to the intergalactic mythology of the church; he also issues frequent memos to update internal procedures and policies. He holds a tight rein on the church's affairs, even though he's officially retired. He personally receives a percentage for every member who buys a course or attends a conference or pays for an auditing session. Employees of the church are paid on commission and are pressured to keep recruiting more and more.

For all that the Church of Scientology claims to work for the benefit of humanity, it has a fiercely aggressive side when it comes to recruiting followers and dealing with critics. It specifically targets people who are going through personal difficulties to leverage their vulnerability and promise them a nonjudgmental ear, only to hook them with endless merchandise, courses, and lectures, with constantly changing requisites but no permission to fail. It punishes deserters with social ostracism and demands humiliating demonstrations from those who return. It teaches its members to mistrust and hate anyone who speaks against Scientology ("We do not find critics of Scientology who do not have criminal pasts") and any organization that independently adopts the techniques of dianetics without Hubbard's blessing ("They are declared enemies of mankind, the planet, and all life"). It launches vicious attack campaigns against actual psychologists, accusing them of torturing patients and even of being allied with foreign enemies.

Malko's conclusion on Scientology is that it teaches a crass oversimplification of human complexity, and the form of honesty that it instills in its members is a mere performance. The most dangerous aspect of its method is that it barely technically misses the standard that defines brainwashing: regular brainwashing is done by force, whereas Scientology convinces its members to do it happily to themselves. In Malko's words, "If […] you accept the definition and believe yourself to be a bundle of chaotic distortions and spiritual contradictions […] then whatever tampering is done to your psyche is nothing less than what you have 'agreed' you want done…"

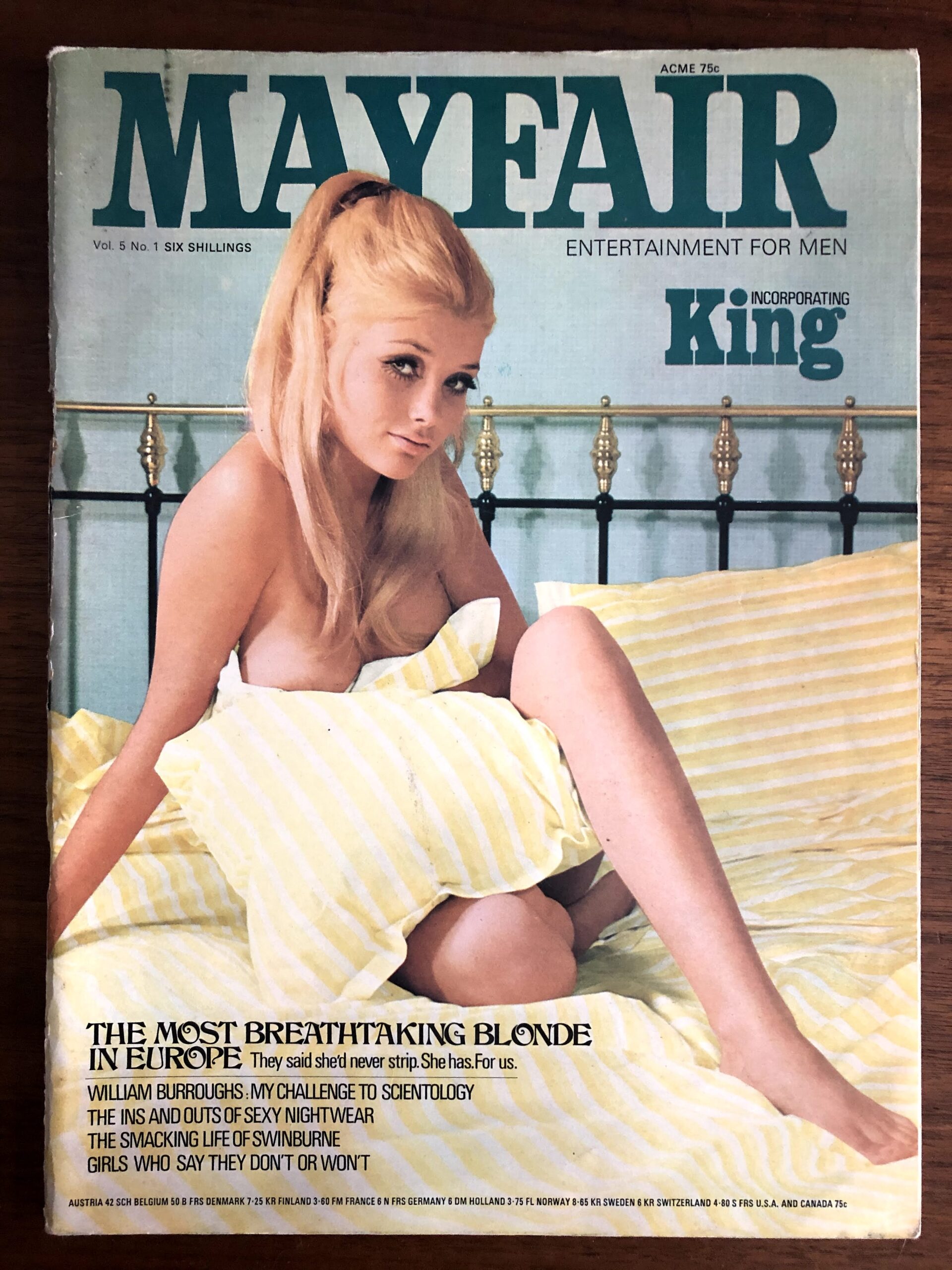

Malko is not the first to raise strong objections to Scientology. Former member William S. Burroughs, of Naked Lunch fame, has been voicing his concerns for a while now. He still believes in most of the doctrine, but disagrees with the totalitarian control that Hubbard has over the church. Last January, he launched a challenge in the pages of the gentlemen's magazine Mayfair: Hubbard should release the contents of the higher "clear" and "operating thetan" courses to the public eye, so that anyone can examine for themselves their validity without having to part with a small fortune. Burroughs also takes issue with Hubbard's grandiose statements about the cosmic importance of his work: "If Mr. Hubbard were content to be a technician who has made some important discoveries we could afford to ignore his personal opinion. When he sets himself up as the saviour of all possible universes we cannot."

And last December, journalist Paulette Cooper, who helpfully has degrees in psychology and comparative religion, published in the ladies' magazine Queen the results of her investigation into the church's abusive practices. In her article, with the inviting title The Tragi-Farce of Scientology, she goes into disturbing detail about the moral implications of some of its doctrines: "[…] a Scientologist can seduce a fifteen-year-old girl because she's really over seventy trillion plus fifteen years old […]" I recommend you read the full article. The horror only gets worse from there.

Malko’s book is worth a read. You can then decide for yourself the degree of threat posed by Scientology’s siren song. If you have been conflicted lately and are seeking out solace, you may very well save your soul.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]