For our second of July's Galactoscopes, we have quite the mixed bag: two winners and two losers. Aren't you glad you've got us to navigate the dross for you?

by Winona Menezes

Quest for the Future, by A.E. Van Vogt

cover by John Schoenherr

Quest for the Future is my first novel by A.E. Van Vogt, though I am familiar with his short stories. Unfortunately, I am going to have to suggest that he stick to the short stories, as I didn’t enjoy this book very much at all.

While trying to rent educational films for his high school classroom, physicist Peter Caxton discovers a mix-up; dazzling scenes of alien worlds and technologically advanced human societies spring forth from the projector with startling clarity. In what will become a recurring motif in this novel, Caxton’s sexual indiscretions force him to realize very predictable consequences; in this case, he must resign from his job in disgrace and comes home to divorce papers from his wife. Having lost everything, he devotes himself to the project of determining the origin of the extraordinary tapes, and discovers an organization specializing in time travel from the distant future that might be able to offer him the key to immortality. Why he would want to prolong his pitiful life any further is never explained and entirely beyond me.

This novel is a serialization of a few of Van Vogt’s stories, though the stories don’t really have much to do with each other. He just strings them together and has Caxton stand in for the protagonists, though I’ll admit the plot justifications are a little creative. Van Vogt’s writing style is also very disjointed, jumping from scene to scene and thought to thought as if he simply doesn’t have time to wait for the reader to catch up. I might have found this style interesting if the plot were more cohesive, but it was not, so following along felt more like a chore. The reason I kept the plot summary short is that trying to describe this book feels like trying to explain a feverish dream which started slipping through the cracks of my memory as soon as I woke up.

I want to finish by mentioning that I usually don’t comment too much on the male chauvinism of male authors, and this is always a conscious choice, not an oversight. Ladies, I know I wouldn’t be breaking any news by informing you that yet another one of these guys is being sexist, and if I pointed it out every time we’d be here all day. I’m here to have fun, but I at least ask that the rest of the story have any redeeming qualities. This one had no flowery prose, no fast-paced action, and little in the way of creativity. The only thing I can say is that our protagonist was so insufferable that it did bring me some satisfaction to watch him flail about ruining his own life. Van Vogt has fallen into the trap of accidentally writing a female character far more interesting than the bone-headed lead, but not being creative enough to make this story about her. Instead we have to follow this idiot Caxton through time and space, hearing every last lecherous thought that oozes through his thick skull.

I understand that the actions and feelings of a character do not necessarily directly reflect the author’s values. It is perfectly possible that Van Vogt is imaginative enough to conjure a story about a boring, disgusting man entirely divorced from his own personality. But if it was possible for him to do that, it was also possible for him to write a story about literally anyone else, and boy do I wish he had done so. I really tried with this one, but I have to give it one star.

By Mx Kris Vyas-Myall

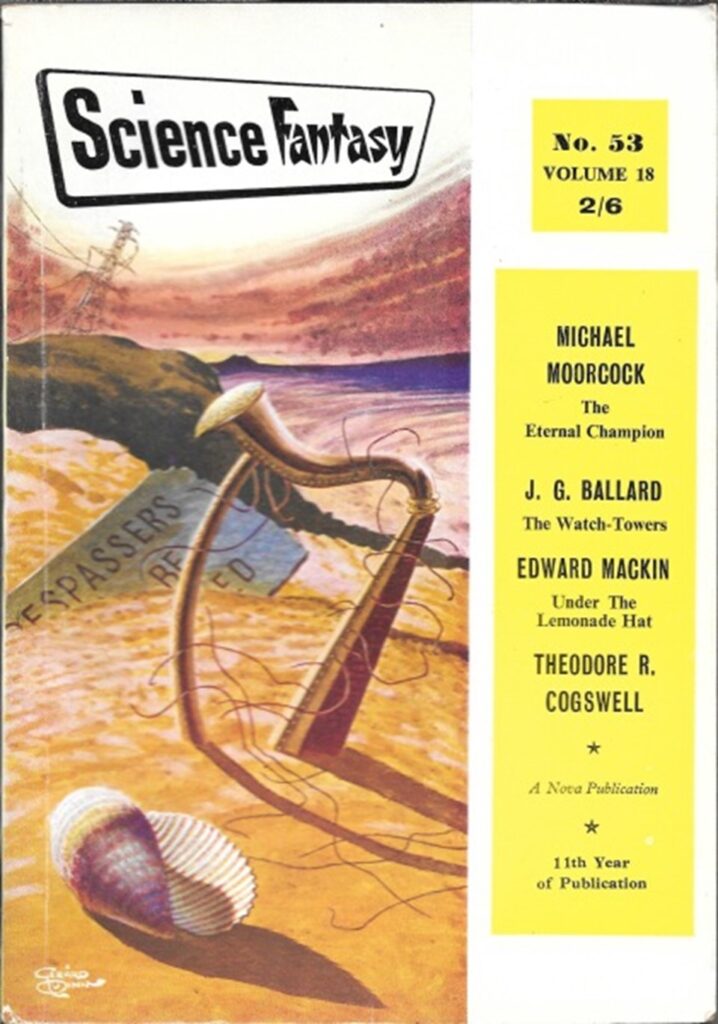

The Eternal Champion, by Michael Moorcock

Cover by Bob Haberfield – Making it look more like a Grateful Dead album than a fantasy novel

In the moments between sleep and wakefulness, John Daker sees strange hallucinations. Names and places he has neither heard nor seen before. The strongest of all are a king and princess calling him to battle against the hounds of evil.

One day, Daker finds himself free of his body and travelling to a new Earth. On this one there is war brewing between humanity and the Eldren. The line of the Warrior Kings of Necranal is almost over, with King Rigenos in deep old age and only his daughter Iolinda left of his family. They are attempting to revive the long dead warrior Erekosë.

John Daker is resurrected as Erekosë and, with his radioactive sword Kanajana, on him rests the hope of humanity. There are two problems, however:

1. He is not convinced if this war is really justified.

2. He does not have many memories of Erekosë and instead has flashes of other lives, such as being a black sword welding albino, a foppish super spy or a time traveller searching for Jesus….

This is built on the bones of the sword & sorcery style but this is not your standard adventure tale. It could probably be said to be an anti-sword & sorcery novel, as it takes the ideas and pushes them to the extremes in order to question the central premises of the genre.

There is clearly a criticism underneath this of the inherent pointlessness of war and indeed the fruitlessness of being the Eternal Champion. Daker does not see the constant battles to save these worlds as glorious but a senseless endless wheel without rest. And this world may be the worst because, in attempting to protect humanity, he is serving genocidal slavers. To quote one of Daker’s dreams:

WHERE DID I COME FROM?

You have always been.

WHERE WILL I GO?

Where you must.

FOR WHAT PURPOSE?

To Fight.

TO FIGHT FOR WHAT?

To Fight.

FOR WHAT?

To Fight.

FOR WHAT?

To Fight.

Moorcock throughout is a master of little narrative touches to create the real sense of weariness of the endless struggle.

At the same time, there are regular references to the possibility that Daker may have had a nervous breakdown and is instead just incarcerated in a mental hospital. But, whether that is the case or not, it is also an inditement of humanity. That the level of hate and irrationality we see on display is regularly exhibited by some in our daily lives for the Other.

This is an expansion of a novella from Science Fantasy back in 1962 (which is itself a completion of an abandoned fanzine serial from the 50s) but there is one change that requires particular notice. In the original story he references real world mythological figures e.g.:

And the names? Was I John Daker or Erekose? Was I either of these? Many other names, Shaleen, Artos, Brian, Umpata, Roland, Ilanth, Ulysses, Alric, fled away down the ghostly rivers of my memory.

But he has changed this to referencing his own works:

And the names? Was I John Daker or Erekosë? Was I either of these? Many other names – Corom Bannan Flurrun, Aubec, Elric, Rackhir, Simon, Cornelius, Asquinol, Hawkmoon

This is not the first time we have seen this, he has talked about his “multiverse” in The Sundered Worlds, The Wrecks of Time & A Cure For Cancer and made a similar point in the recent Jerry Cornelius story The Peking Junction. But this work has put it front and centre as the core of the tale. Whilst I will list all the references I found the footnotes later, and I think it is worth talking about some of the figures who are also “Eternal Champions” compared to John Daker/Erekose:

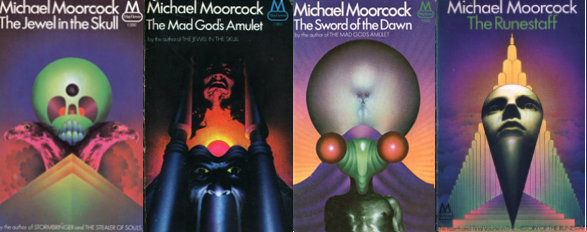

Covers by Bob Haberfield – Making it look like the Wizard of Oz reinterpreted by King Crimson

The Jewel In The Skull Quartet:

Hawkmoon…I saw towers and marshes and lakes and armies and lances that shot flames and metallic flying machines whose wings flapped like those of gigantic birds. I saw monstorously large flamingos, strange mask-like helmets resembling the face of beasts… Köln

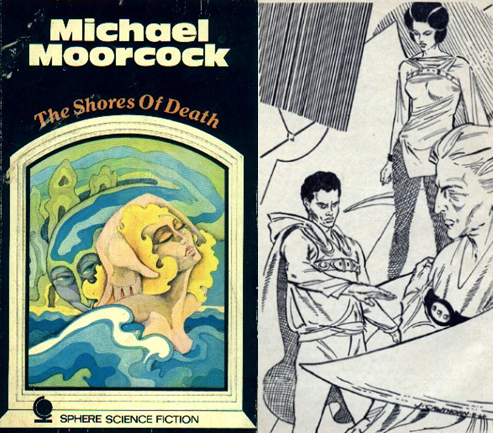

Cover (L) by Bill Botten, internal image (R) by James Cawthorn

I saw Earth but this was an Earth without a Moon. An Earth which did not rotate, which was half in starlight and half in a darkness relieved only by the stars. And there was strife here, too, and a morbid quest that as good as destroyed me…. name – Clarvis? Something of the sort….Marca

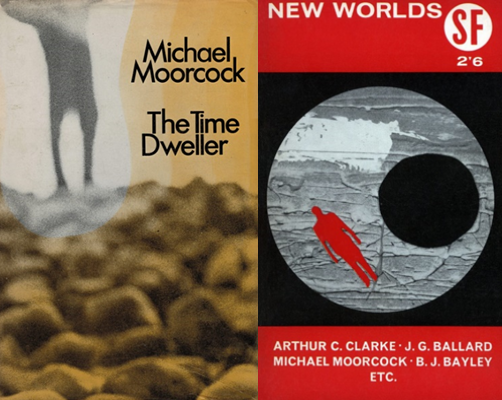

The Time Dweller/Escape From Evening:

Artists uncredited

I saw Earth – a different Earth again. An Earth which was so old that even the seas had begun to dry up. And I rode across a murky landscape, beneath a tiny sun, and I thought about time…another name – The Chronarch…Lanjis Liho…Pepin

This one is interesting as it refers to three different characters from these tales. Whilst I think talking about The Chronarch is likely just contextual, but it seems to imply to me that both Lanjis Liho and Pepin the Hunchback may both be Eternal Champions.

And perhaps, most curiously The Authors:

Colvin, Bradbury…

Now Moorcock’s name is not directly mentioned here, but he includes two of the pseudonyms he uses. This leads to an interesting idea. Is an author in themselves an Eternal Champion? By telling these stories are you able to tip the balance between order and chaos? I do not know if this is what he intends with these names, but it is an interesting idea to think about.

A couple of words of warning: Firstly, this book is grim. It is done to a purpose and avoids dwelling in gratuitousness, but we are talking child murder and war crimes being a core part of the narrative. If you go in expecting a jolly romp, you are going to be thoroughly disappointed.

Secondly, a number of the characters could possibly have done with being fleshed out more and can feel a little stock. Iolinda, in particular, I feel suffers most from this. The effect may be intentional with us feeling detached from humanity just as Daker is. But it also makes for a tougher reading experience.

None of this, however, moves away from how interesting and important I feel this book is and I will give a full Five Stars.

And here is the full list of possible Eternal Champions as as I noted:

Alan Powys (The Fireclown); Prince Asquinol of Pompeii (The Sundered Worlds); Earl Aubec (Master of Chaos); Clovis Marca (The Shores of Death); Prince Corom Bannan Flannan of The Scarlet Robe (According to a friend in the know, this is from the soon to be released The Knight of Swords); Dietrich von Bern (legendary figure of whom Moorcock has said he based Hawkmoon on); Dorian Hawkmoon, Duke of Köln (Jewel in the Skull et al); Edward P. Bradbury (faux writer of the Martian Trilogy) & James Colvin (second pseudonym of Moorcock); Elric of Melniboné (Stormbringer et al); Prof. Faustaff (Wrecks of Time); Hallner (The Mountain); Jepharim Tallow (The Golden Barge); Jerry Cornelius (The Final Programme et al); John Daker/Erekosë (The Eternal Champion); Jonathan Mennell (Consuming Passion); Karl Galouger (Behold the Man); Konrad Arflane (The Ice Schooner); Lanjis Liho (The Time Dweller/Escape from Evening), Pepin Hunchback (Escape From Evening) and The Chronarch (Time Dweller); Prof. Lee Seward (Deep Fix); London (Could be several or just referencing the city itself); Maldoon (The Ruins); Investigator Minos Aquillinas (The Pleasure Garden of Felipe Sagittarius); Agent Nick Allard (The LSD Dossier et al); Rackhir the Red Archer (To Rescue Tanelorn); Ryan (The Black Corridor); Simon of Byzantium (The Greater Conqueror); Sojan the Swordsman (Various stories in Tarzan Adventures); Traven (JG Ballard’s Terminal Beach/Assassination Weapon)

by Maureen Hogan

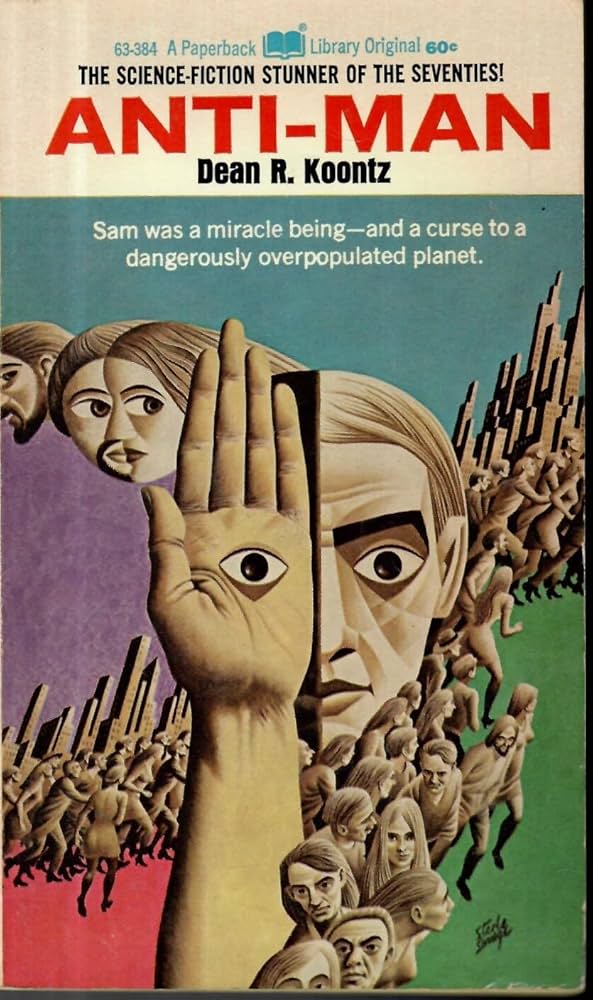

Anti-Man, by Dean Koontz

cover by Steele Savage

Anti-Man follows the story of Dr. Jacob Kennelman and “Sam”: one man, one android, both fugitives of the World Authority. (Sam is a bit of a misnomer. Dr. Kennelman can’t seem to find a good name for “Sam”, opting to refer to Him with a capital “H” throughout the book.). The authorities are desperate to destroy Sam because his healing abilities are so powerful they can quite literally resurrect the dead. In a world that is suffering from extreme overpopulation, this could spell disaster (though it’s never stated exactly how…). As a doctor, Kennelman couldn’t stand to destroy someone who could cure human ails, so he decides to kidnap Sam and go on the run. (Though Sam is completely on board with this plan, so I guess it technically isn’t a kidnapping. But, I’m just being pedantic).

Our dynamic duo are the strongest of the bunch in terms of characterization. Koontz’s use of first-person narration frames Dr. Kennelman as a man truly out of his depth. It adds much needed emotion and stakes to action and horror scenes. However, it does mean that the dear doctor is prone to go on expository monologues explaining the world’s history and technology for our benefit. Sam is downright weird, and it’s fantastic. We start with you’d expect from an android: an uncanny human figure far smarter and stronger that any man. He has the power to reshape himself and others on a cellular levels, which is at times extremely useful (healing and resurrection) and downright terrifying (growing into an amoeba-like blob that spans an entire basement). Sam’s power set makes for an interesting companion (try hiding your true motives from a mind reader), though there is some inconsistencies in what he can and cannot do. [Note: This portion of the story appears to have been concurrently published as the short story The Mystery of His Flesh (ed.)]

If you’re a fan of lovable side characters, you’re out of luck. The other male characters are rather flat, and the female characters are basically non-existent. (I don’t remember Dr. Kennelman having an actual conversation with a woman in the whole book. If it happened, it obviously was not very memorable.)

In the second half of the book, one of Koontz’s plot twists really didn't sit right with me. (I will try my best to convey my thoughts without utterly ruining it for you.) I read the pages following the reveal in a mix of confusion and irritation. It seriously felt like this would ruin my enjoyment of the book. I ended up getting too impatient and indulging in a reader’s faux pas… I skipped a few chapters to see how the twist resolved. Satisfied, I returned to my previous place and read the book in its entirety. In retrospect, Koontz was trying to set this twist up through Kennelman’s supposed distrust of Sam. (The doctor would go back and forth between blind trust and suspicion like a swinging pendulum. These two extremes made me question Kennelman’s doubts, and whether Koontz would deliver on them.) Maybe, dear reader, you’ll be less annoyed by the twist and find it more engaging.

The final breakdown:

Concepts: 4/5 for inventive technology and horror imagery

Writing Style: 2/5 for strong first-person narration, but lengthy exposition and strange syntax

Story Structure: 2/5 for a strong foundation, but a weaker resolution with an unfavorable twist and some plot holes.

Average it all up, and we get 2.7 out of 5 stars, rounding down to 2.5.

by Amber Dubin

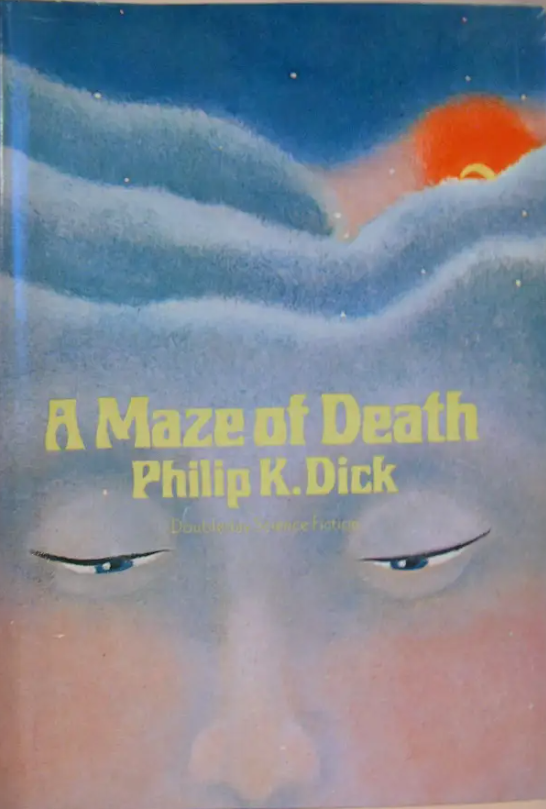

A Maze of Death, by Philip K. Dick

cover by Michelle Moschella

God is real. Prayers are processed and receive direct responses. Angels exist, interact with humans, prevent mistakes, and dispense tangible blessings. Are you intrigued? I certainly was. A Maze of Death by Philip K. Dick was a surprising, incredibly compelling and unique work that kept me mystified as to what was going on all the way to the last page.

Unlike the last several authors I’ve read lately, Philip K. Dick’s reputation preceded him. If I had not already heard glowing praise for some of his other works by fellow Galactoscope writers, the cover proclaimed this author a Hugo award winner, and the snippets it lists from the book itself were too fascinating to ignore. My expectations, therefore, were high going in, and somehow they were exceeded by quite the margin.

The way the text is laid out itself is something I’ve never seen before, in that every single word on every page is important. The pre-book author’s note, review blurbs, even the table of contents play into a stage setting that left me wholly unprepared for the contents within. Firstly, at no point does any plot summary or review note mention my favorite part of this book and that is the world’s background. We are supposed to be dropped in a world where the pre-author’s note appears to “helpfully” be inspired by an acid-trip’s version of death/the afterlife. I thus expected esoteric fantasy with colorful descriptions I’d have to squint at to make out what was going on.

From the very beginning, this world is the complete opposite: God has been encountered via space-travel. He is an immortal alien named The Mentufacturer, he has an emissary who was born mortal but transcended said bindings of mortality like Christ, but named The Intercessor, and he and his various manifestations directly interact with humans and other sentient species on a regular basis, giving them advice that sometimes avoids fatal errors, passing judgement in the form of progress reports and insight into the qualities of one’s soul/personality. What’s more, prayers are quantified, can be directly uploaded from a forehead implant plugged into a physical network and can and will be processed and responded to based on priority, realistic nature of subject matter/request, worthiness of the petitioner and distance travelled from the center of Influence.

Yes, there is a physical God-world to which these prayers have to travel and from which the signal diminishes upon distance to the central concentric circle touched by The Deity’s literal Sphere of Influence. It is further explained that said deity is not omniscient and all-powerful, as at the outer edges of this sphere (essentially at a metaphorical Pluto distance to the Sun in Earth’s solar system), His influence and knowledge diminishes, thus allowing the influence of a counter-being: The Form Destroyer, to have greater power to cause death, decay, and unregulated destruction at his own will. This explains why, in the before-times (vaguely our contemporary era) on earth, we were unable to tap into the Mentufacturer’s network and receive His blessings, because we had not travelled far enough through space to enter the orbit of His God-world.

The most amazing part of this for me is that even though there is definitive proof that God, a Devil, a Judgement Day, Christ, and even Miracles exist and all of these truths are laid out tangibly in a Bible-esque book (hilariously named How I Rose From the Dead in My Spare Time and So Can You by A.J. Specktowsky), there still exist Jews, Gentiles, and, shockingly, Atheists. For me, that is the most grounded aspect of this novel, that somehow a new religion is the new law of the human species and yet some of us still cling to our old beliefs; that even when an atheist can travel to a physical planet to meet a god that is contactable via messenger system, he would still choose to firmly believe the entire system that directs his universe and directly influences his life is metaphorical.

In a darker shadow of this seemingly flawless, benevolent, and all-consuming new religious societal structure, we find out that, although atheists are somehow not punished for their lack of belief, there is a sub-group of people who are determined to be a threat to the system. They are labeled “ostriches” and are determined to be criminally insane, sequestered in facilities labeled “aviaries” for implied rehabilitation/reconditioning. Not much is detailed about this aspect of society, how you qualify for entrance to such a facility or to be released from it, other than they are looked down on by everyone else.

As riveting as this backdrop is, there is plenty more to the book. Just as the table of contents features chapter summaries that are all patent lies, the plot of this novel uses misdirection and random irrelevant information to keep the reader guessing as to what is going on. There are 14 people, but the narration flits between them so often you’re left with the sense that there is no one main character and none is more important than the other. The general sense that you get is that The Mentufacturer arranged to have all these unique individuals gathered at a settlement called Delmark-O, each from their separate lives on other planets throughout the galaxy where they conducted jobs as varied in theme and importance as a marine biologist, an economist, a photographer, a psychologist and a linguist. Their purpose in the recruitment has been scrambled by a mistake in the satellite meant to send the recording once they all arrived. They at first are consoled in their lack of direction, by the knowledge that at least one of the recruits was transferred there as a direct answer to his prayer from the Mentufacturer, but unease quickly takes back over as the recruits begin to die, in distinct, mysterious fashions that could be the work of a serial murderer, several culprits, or direct intervention by the anti-God Form Destroyer Himself.

Despite what I thought were my finely honed detective instincts, I only was able to get vague inclinations as to what was truly going on and why by the time all was revealed, and even towards the end as their reality darkened into depths I didn’t think possible, the final few twists kept me asking questions all the way to the last words. It takes a lot to keep me engaged, continually curious and surprised as this did, and Philip K Dick did a whole lot of that in a very few amount of pages. I’m impressed.

This was the best literary experience I've had in a very long while. I’m officially a Philip K. Dick fan.

5+ stars.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]