Tune in tonight at 7pm Pacific for the latest episode of Science Fiction Theater!

by Cora Buhlert

This is not the article I was planning to write this month. In fact, I was going to review the Ballantine Adult Fantasy collection Zotique, which reprints the haunting stories Clark Ashton Smith published in Weird Tales for the first time in more than thirty years.

However, Clark Ashton Smith will have to wait – he has been waiting for more than thirty years by now, after all – because there have been some most shocking developments in the West German leftwing sphere.

A Pleasant Spring Day in West Berlin

The Dahlem neighbourhood of West Berlin is a normally a quiet upper middle class suburb, where nineteenth and early twentieth mansions line leafy cobblestoned streets. There is little traffic here, birdsong can be heard echoing from the gardens and rarely are there sounds louder than a whirring of a lawnmower or the barking of a dog. But on May 14 at eleven AM, the quiet of Dahlem was interrupted by the sound of gunfire.

The source of those shots was a white mansion with dark green shutters, nestled in a garden with birch and pine trees on Miquelstraße. It was a warm and sunny spring day, so the windows on the ground floor were wide open. This mansion houses the library of the German Central Institute for Social Issues, i.e. not a place where anybody would expect gunfire.

Shortly after the shots, an engine howled and a car raced down the street. Georg Linke, the 62-year-old janitor of the Institute, staggered across Miquelstraße, clutching his side, only to collapse in a driveway, bleeding profusely from gunshot wounds in his arm and his abdomen. He was found by a student who wanted to consult the library.

"That was the Meinhof woman," a man in uniform yelled from the open window of the Institute, while the student yelled back they should call an ambulance, because someone had been shot.

Initially, there was some confusion about what precisely had happened at the German Central Institute for Social Issues. But gradually, it became clear that the quiet Miquelstraße had just witnessed one of the boldest prison breaks in recent German history.

Arsonists on the Run

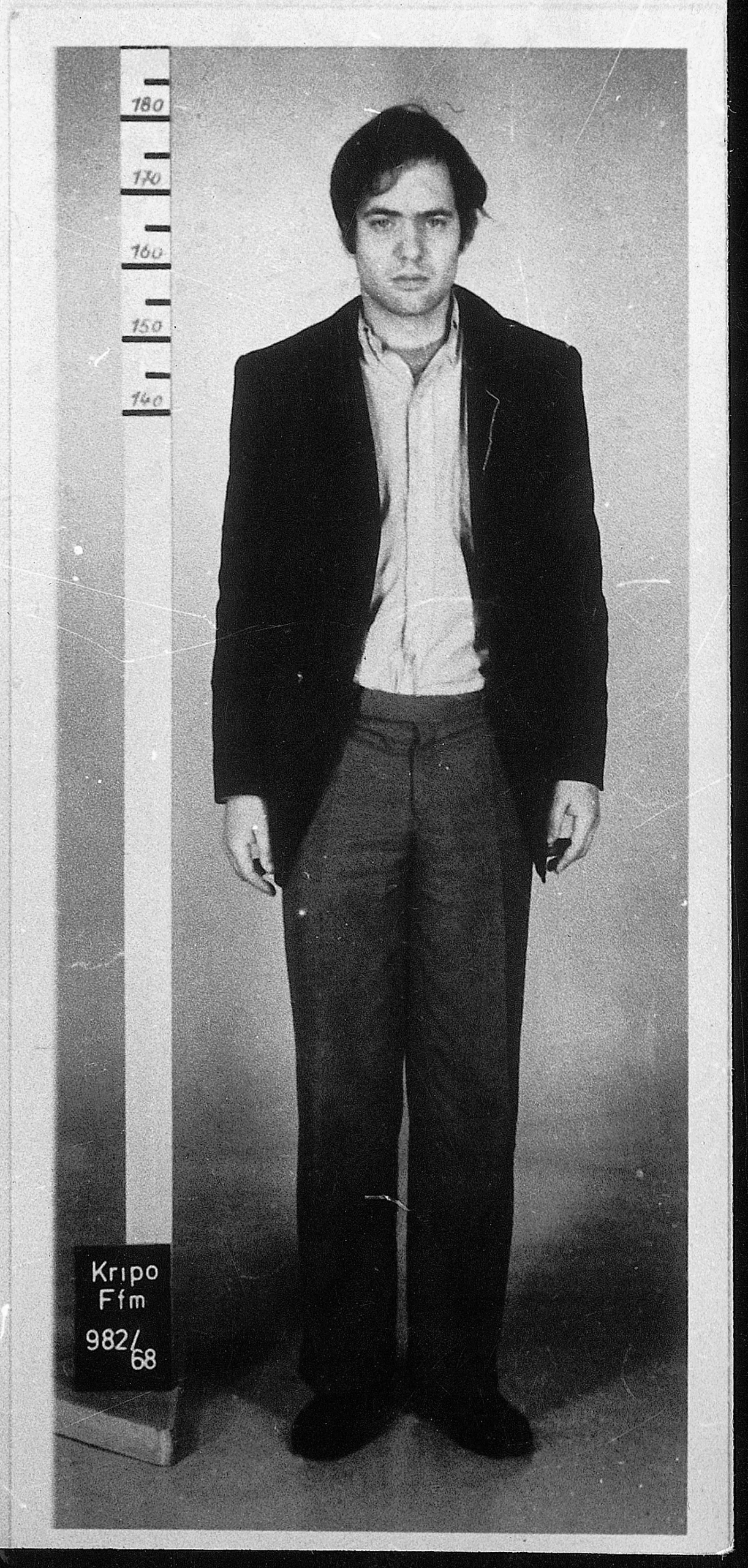

Two years ago, I reported in these pages that a quartet of young idiotic would-be revolutionaries had committed arson attacks on two department stores in Frankfurt on Main to strike a blow against capitalism, consumerism, the Vietnam War and the West German government. And yes, I'm aware that this make absolutely no sense.

The arsonists were quickly caught and put on trial, which they turned into a spectacle by refusing to answer even basic questions regarding their names and generally behaving very badly. Two of the arsonists, Andreas Baader and Gudrun Ensslin, who are lovers even though they both have children with other people, even made out in court. The judge was not at all impressed and sentenced the quartet to three years in prison each.

That should have been the end of it, except that lawyer Horst Mahler, who represents many of leftwing activists in court, filed an appeal against on behalf of his clients. While the appeal was pending, the defendants were set free. One of the arsonists, Horst Söhnlein, actually did go to prison, once the repeal was rejected. However, Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, and Thorwald Proll promptly used the opportunity to go into hiding. Proll has likely left West Germany by now, but Baader and Ensslin were believed to be hiding out with members of the leftwing protest movement somewhere in West Berlin, while the police were hunting the absconded arsonists.

In April, the police got lucky and arrested Andreas Baader during a routine traffic stop. He was promptly transferred to the prison in Berlin-Tegel where he was supposed to spend the next three years. Of Gudrun Ensslin, there was still no trace.

Wayward Youth

Meanwhile, lawyer Horst Mahler got loud on behalf of his client Andreas Baader. He declared that Andreas Baader was working on a book about troubled youths living in care homes. Of course, Andreas Baader who never even finished school was not exactly the most likely person to write a book. Therefore, Baader had a co-author, who turned out to be none other than Ulrike Meinhof, a leftwing investigative journalist who has appeared in these pages before as well. Ulrike Meinhof has been reporting about the terrible conditions in the often prison-like institutions for wayward youths run by the state or the Christian churches since 1965. She interviewed former inmates, wrote articles, produced radio reports and even a TV movie about the issue. During her research, Ulrike Meinhof met Andreas Baader and Gudrun Ensslin, who had taken part in protests against the terrible conditions in homes for wayward youths in Frankfurt on Main. So the claim that Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof were collaborating on a book about an issue they both clearly cared about was not that far-fetched. And indeed, lawyer Horst Mahler produced a letter from publisher Klaus Wagenbach confirming that Baader and Meinhof were collaborating on a book project.

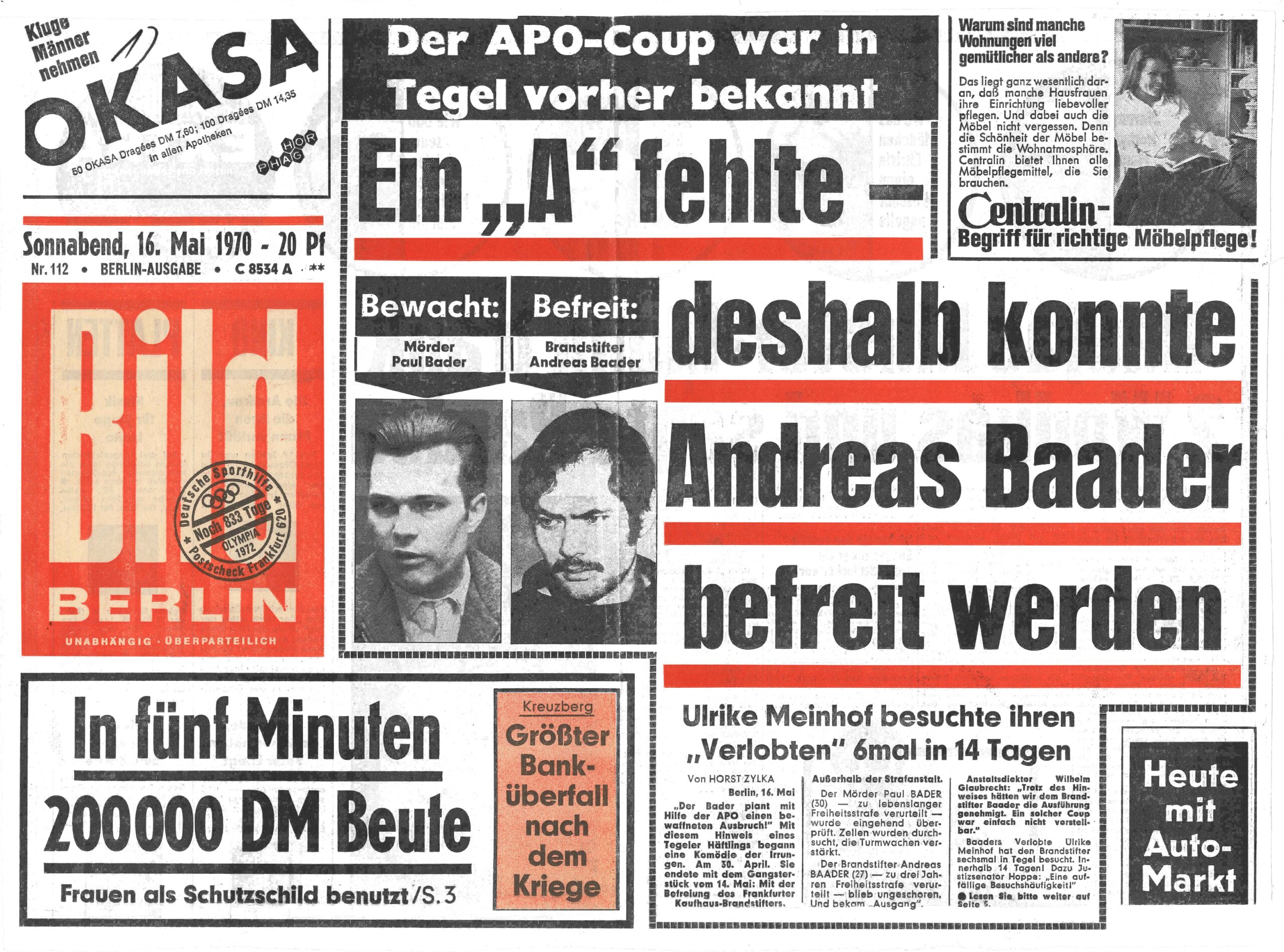

However, with Baader behind bars in Tegel, the book was at risk. In order to complete the book, Baader would absolutely have to consult with his co-author Ulrike Meinhof in person. And no, meeting at the Tegel prison was not sufficient, even though Meinhof visited Baader a whopping 25 times in jail. Because – so Horst Mahler claimed – Baader and Meinhof would have to consult the library of the German Central Institute for Social Issues. Initially, Wilhelm Glaubrecht, the governor of Tegel prison refused, especially since they had been tipped off that someone would try to break a prisoner out, though due to a typo they assumed the prisoner in question was a man named Paul Bader and increased security for the wrong prisoner. However, Horst Mahler was very insistent indeed, so Glaubrecht finally relented and allowed for Andreas Baader to be taken under guard to the German Central Institute for Social Issues to meet up with Ulrike Meinhof. This meeting was to take place on May 14.

Gunshots in the Library

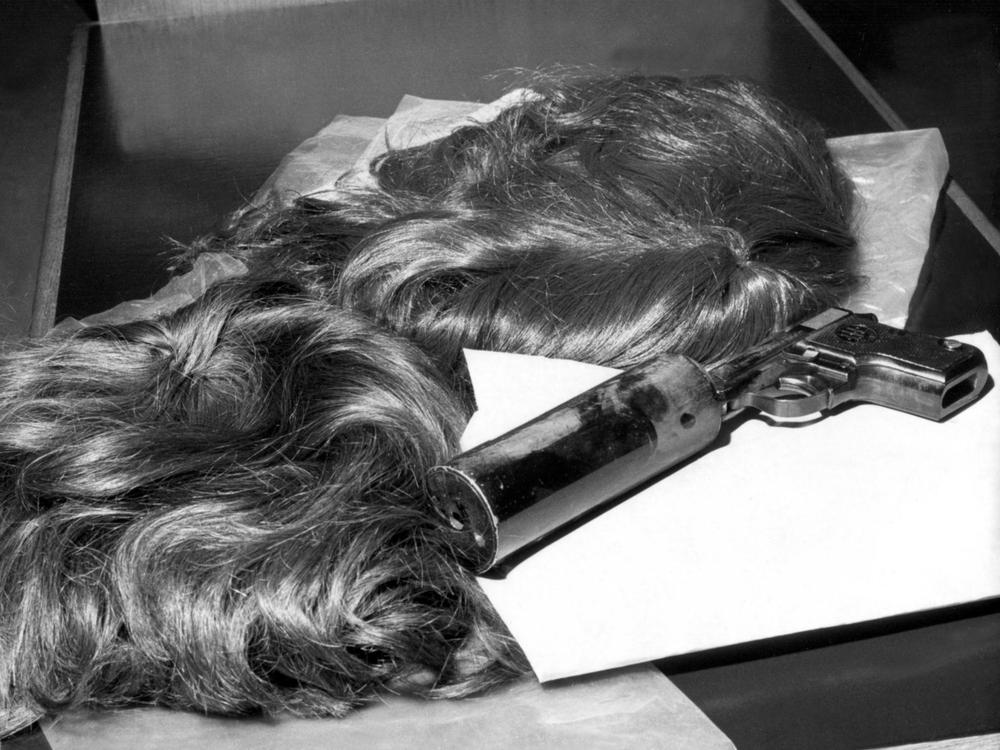

One day before, on May 13, two young women wearing wigs and dark sunglasses showed up at the Institute and claimed that they wanted to consult the library. However, the two women seemed far more interested in the windows and doors of the mansion that housed the library than in any of the books. "We'll be back tomorrow," one of the women said ominously before leaving.

The mysterious women indeed returned the next day, still wearing wigs and dark sunglasses and carrying large handbags. They requested access to the library, but were refused entrance to the reading room, where Ulrike Meinhof and Andreas Baader were already hard at work, surrounded by stacks of books, under the watchful eye of two uniformed prison wardens. Hans Joachim Schneider, an employee at the Insitute, noted that Baader seemed pale and harmless, albeit rather nervous. He and Meinhof were consulting books and making notes, all the while smoking heavily. The air inside the reading room quickly became stale, so one of the wardens opened a window to let in some fresh air.

At around eleven AM, one of the two young women who were still waiting in the lobby of the Institute suddenly got up and opened the front door. Promptly, a woman in a red wig and a masked man stormed into the lobby, brandishing guns. The two young women also pulled guns from their oversized handbags. Together, the four dashed towards the reading room. Janitor Georg Linke heard the tumult and emerged from his office to investigate. The masked man fired and hit Linke in the arm and the abdomen.

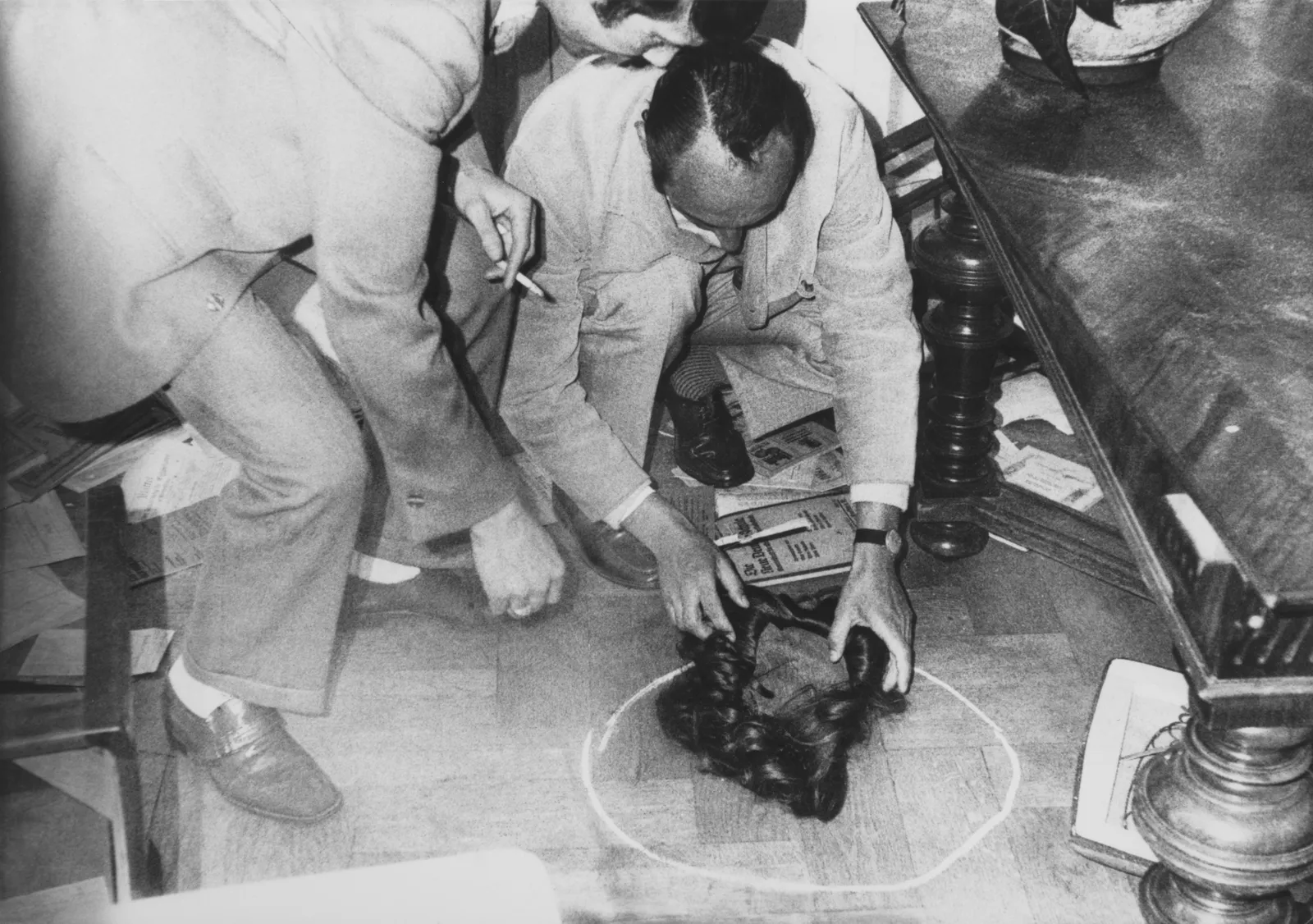

Before the armed guards inside the reading room had time to react, the four armed figures stormed into the room. "Hands up, this is a raid!" one of the women yelled and fired into the ceiling. The guards pulled their own weapons and quickly found themselves engaged in a furious struggle with the two young women, during which both guards were injured. Andreas Baader jumped out of the window, followed after a few seconds of hesitation by Ulrike Meinhof. Meanwhile, the four intruders dashed out of the front door, jumped into a waiting car and drove off.

The two young women left their wigs as well as one of their guns, a Beretta pistol fitted with a silencer, behind, while Ulrike Meinhof left her handbag behind. The getaway car, an Alfa Romeo Guilia Sprint, which had been stolen from a garage the day before, was found abandoned shortly thereafter.

Examining the Evidence

Now, almost two months later, we know a little more about what happened in the library of the German Central Institute for Social Issues on May 14.

It seems that the plot to liberate Andreas Baader was hatched by Gudrun Ensslin and lawyer Horst Mahler. Publisher Klaus Wagenbach has since admitted that Mahler and Ulrike Meinhof asked him to write the letter confirming that Baader was collaborating with Meinhof on a book about wayward youths, though he claims to have had no idea what they were planning, but really thought there would be a book. Wagenbach has published Ulrike Meinhof's work before, so his statements seem credible.

The two young women wearing wigs and sunglasses have since been identified, One is 25-year-old Ingrid Schubert who had completed her studies of medicine at the Free University of (West) Berlin two months before. Little is known about her except that she was invested in leftwing causes and that she told her family during the Easter holidays that she would not start working in a hospital right away, because there was something she needed to do first.

The other wigged woman was identified as 19-year-old Irene Goergens. Born out of wedlock to a German woman and an American GI, Irene Goergens was always something of a troublemaker. At age fourteen she was arrested for vagrancy and sent to a home for wayward youth, where met journalist Ulrike Meinhof during her research into the conditions in such homes. Ulrike Meinhof took the girl under her wing and let her stay at her West Berlin apartment, where she worked as a nanny taking care of Meinhof's twin daughters.

As for the two armed intruders, the woman with the red wig was likely Gudrun Ensslin herself. The identity of the masked intruder is still unknown, though witnesses say it was a man. Lawyer Horst Mahler is a likely candidate, except that Mahler is rather corpulent and the intruder was much leaner. Andreas Baader's co-arsonist Thorwald Proll is a possible suspect – the other co-arsonist Horst Söhnlein is currently in prison – but Proll is believed to have long since left West Germany. Another potential suspect is the journalist Peter Homann, Ulrike Meinhof's current lover who is living with her, Irene Goergens and Ulrike Meinhof's young daughters in her West Berlin flat, especially since Homann has not been seen since May 14 either. However, the masked man might have been someone else from the West Berlin leftwing activist scene or maybe a hired gun. As a lawyer, Horst Mahler certainly has underworld contacts. At any rate, it was this unknown male intruder who shot Georg Linke according to witnesses.

Georg Linke was taken to hospital in critical condition with a wound in his arm and a bullet in his liver. Thankfully, his condition has since improved.

The Baader Meinhof Connection

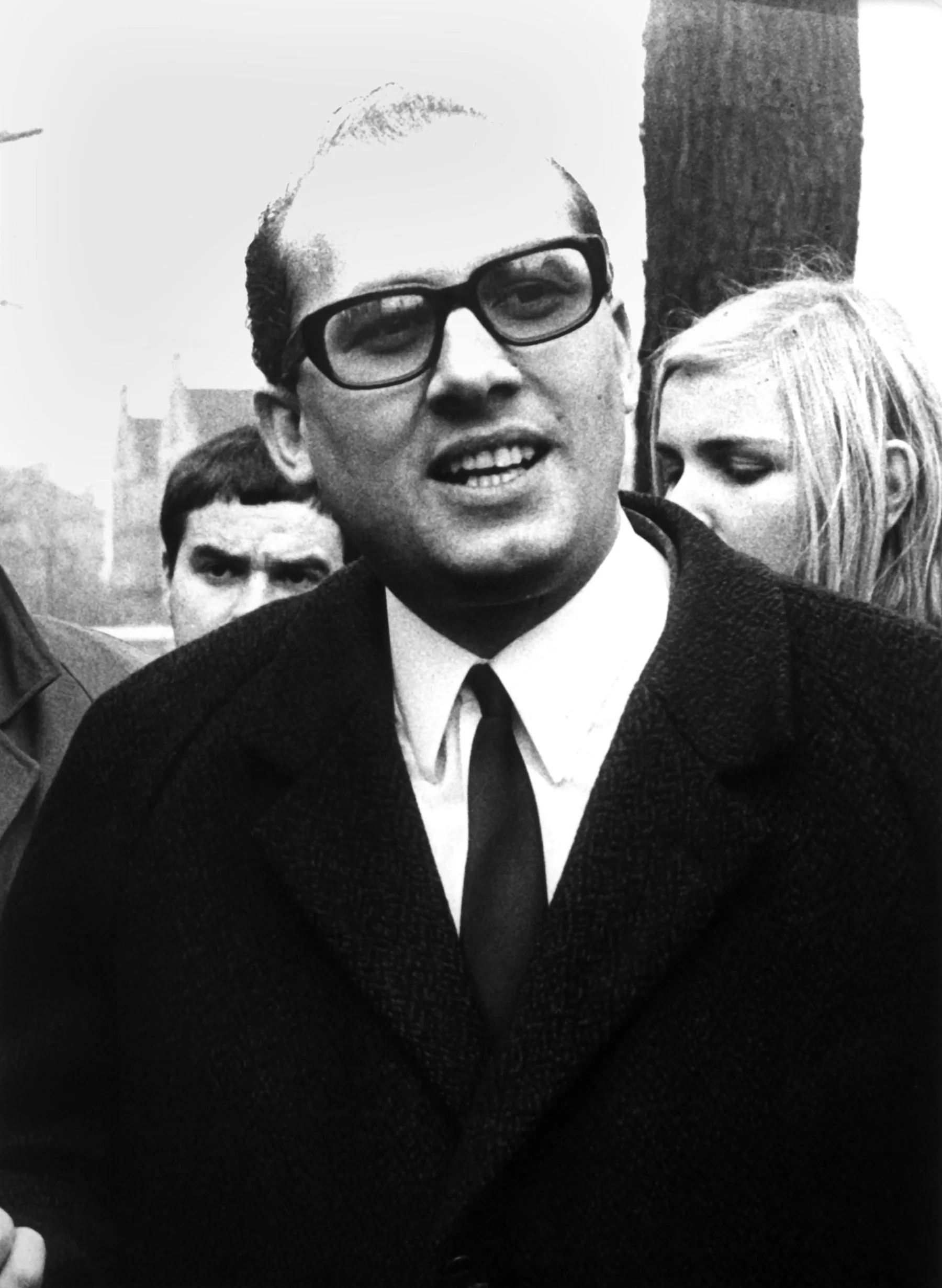

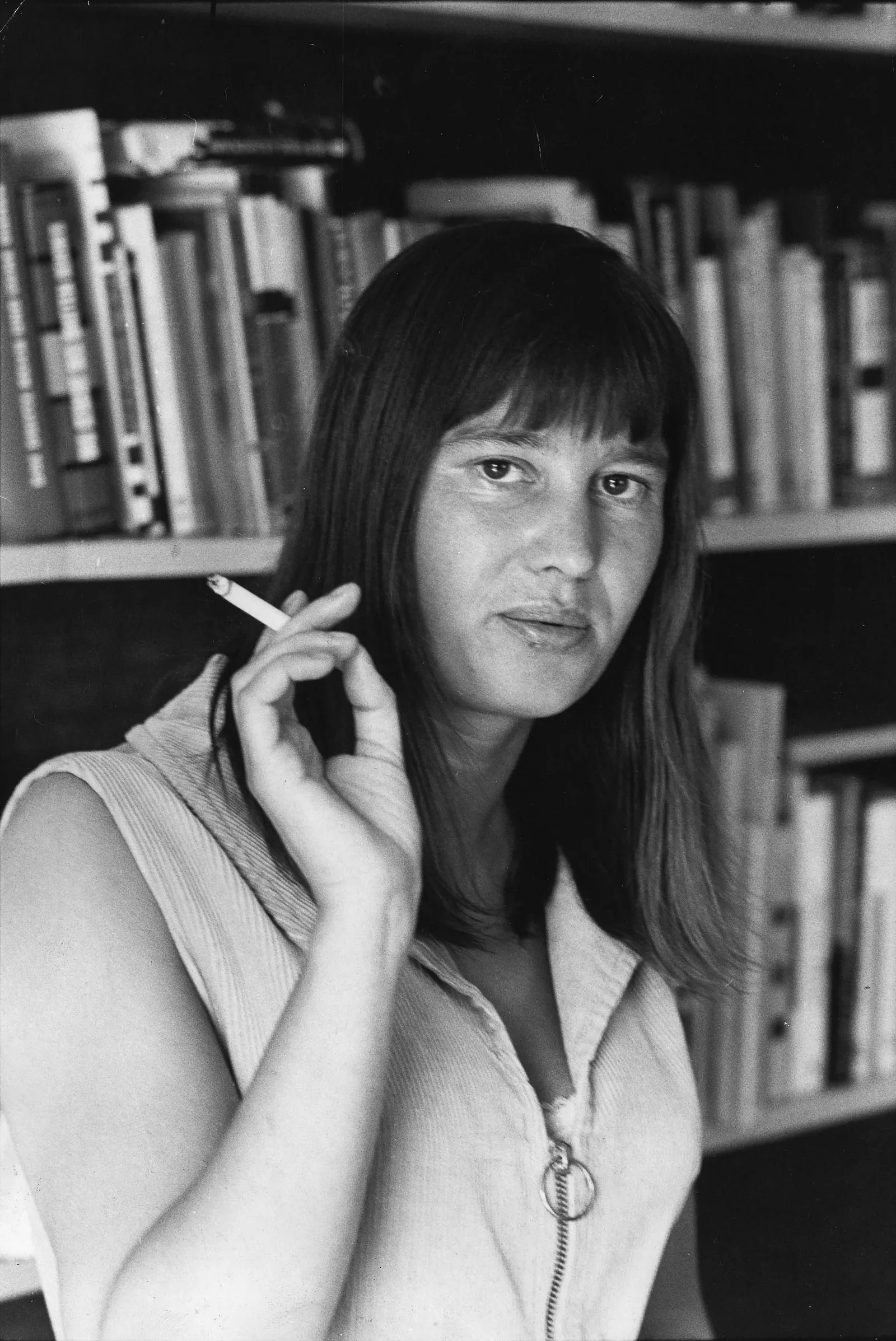

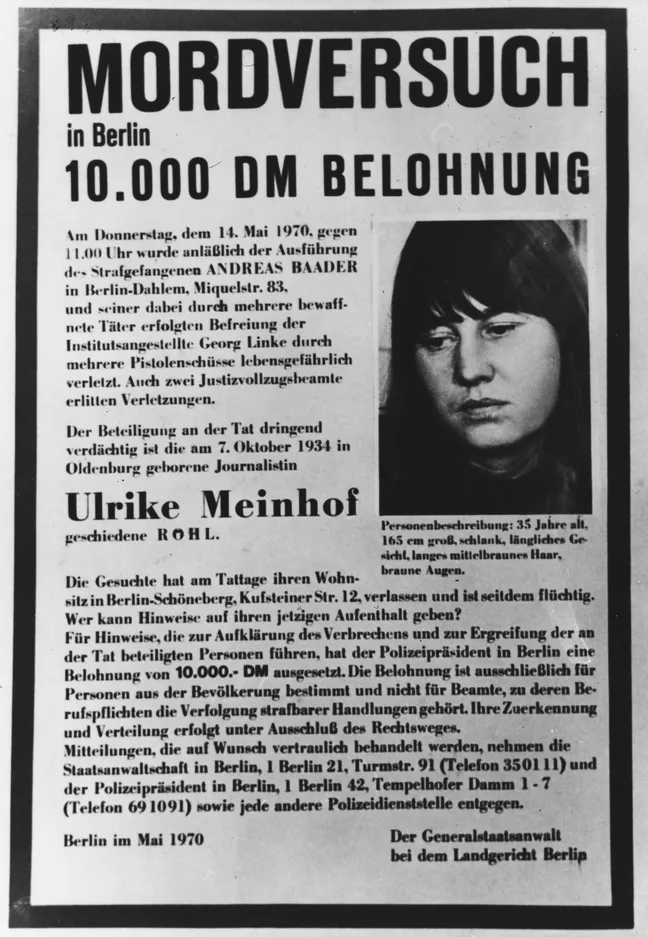

As for Ulrike Meinhof herself, she must have known at least part of what Mahler and Ensslin were planning, though it is not yet clear to what extent she was involved. The West German police and large parts of the press believe that Meinhof was one of the masterminds behind the whole prison break along with Gudrun Ensslin and Horst Mahler. And indeed Wanted posters emblazoned with Ulrike Meinhof's face and the words "Attempted Murder" and "10000 Deutschmarks Reward" can be currently seen on billboards and post office walls all over West Berlin and the rest of West Germany along with the similar posters featuring the faces of Andreas Baader and Gudrun Ensslin. The tabloid press has even started to call the group that broke Andreas Baader out of prison the Baader-Meinhof gang, almost as if they were Depression era gangsters. In fact, it seems as if the manhunt—or rather—womanhunt for Ulrike Meinhof is far more intense than the hunt for Horst Mahler, who was very obviously one of the masterminds behind the plot.

Part of the reason is that Ulrike Meinhof is by far the most prominent of the people involved in the prison break at the German Central Institute for Social Issues. Gudrun Ensslin and Andreas Baader are fringe figures in the leftwing activist scene of West Berlin, barely known before they committed the arson attacks. As an activist lawyer, Horst Mahler is better known and occasionally shows up in the news, but the focus is on his clients rather than on Mahler himself.

Ulrike Meinhof, however, is a celebrity, a journalist who penned countless much discussed articles, produced radio features and even appeared on TV, in discussion rounds and as a producer of documentaries and TV movies. I would not necessarily recognise Andreas Baader or Gudrun Ensslin or Horst Mahler, if I met them on the street, but I would recognise Ulrike Meinhof.

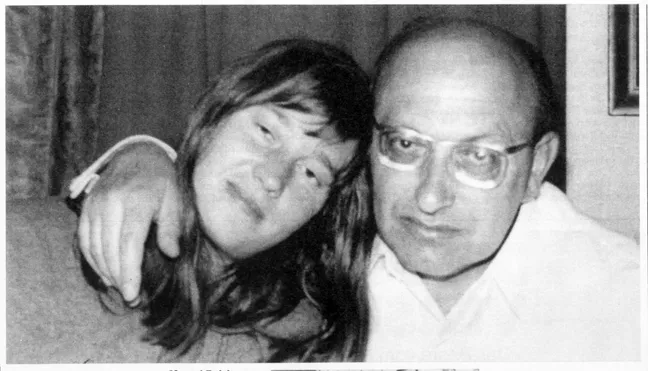

Nonetheless, the questions remains how deeply Ulrike Meinhof was involved in the plot to free Andreas Baader. So let's examine the evidence. We know that Ulrike Meinhof has known Baader and Ensslin for at least three years and was friendly with them. They worked together on projects to reform homes for wayward youths. Ulrike Meinhof also covered the trial against Baader, Ensslin and their co-conspirators for the Frankfurt arson attacks and interviewed Gudrun Ensslin in prison. Furthermore, it turned out that Baader and Ensslin had been staying at Meinhof's apartment in West Berlin, while they were hiding from the police.

What is more, Irene Goergens, who was staying with Meinhof and working for her as a nanny, was definitely involved in the plot as one of the two women who staked out the Institute. So unless Irene Goergens and Gudrun Ensslin were somehow conspiring behind Meinhof's back, she must have known something.

Additional evidence that Ulrike Meinhof at least had some idea about what Horst Mahler and Gudrun Ensslin were planning is the fate of her eight-year-old twin daughters Bettina and Regine. The girls were living with Meinhof in West Berlin after her divorce. After the prison break, the girls' father, Meinhof's estranged ex-husband publisher Klaus Rainer Röhl filed for and was granted custody of his daughters. However, when he came to pick them up, he found that the girls had vanished from Meinhof's apartment in West Berlin. It turned out that Ulrike Meinhof had sent her daughters to Bremen to stay with a friend of hers on May 15, i.e. one day after she became one of West Germany's most wanted. Meinhof also issued a statement via her lawyer Heinrich Hannover, who's a well-known leftwing lawyer here in Bremen, that she intends to retain custody of her daughters and wants them to stay with her older sister rather their father for the time being. Not long thereafter, the two girls vanished from Bremen as well. Their current whereabouts are unknown, but I fervently hope that they are fine, because these two eight-year-old girls are wholly innocent of everything that happened.

And talking of children, Gudrun Ensslin, who is so concerned about the terrible conditions in West German's children's homes, would rather see her three-year-old son Felix languish in just such a children's home after her arrest for arson than live with his father or her family.

Ulrike Meinhof Speaks

However, Ulrike Meinhof also had more to say in the statement she issued via her lawyer. She claimed that she had no idea what Mahler and Ensslin were planning and she certainly hadn't attempted to murder anyone. The latter is most likely true, because Meinhof's handbag was found at the crime scene. Inside the handbag, there was a mortgage deed, not exactly a common thing to carry around, but no weapon. And witnesses state that the janitor Georg Linke was shot by the masked man, not by Meinhof.

As for why she jumped out of the window and ran away, Ulrike Meinhof claims to be have been confused and frightened, because things hadn't gone to plan, which invites the question just what exactly she thought the plan was.

Finally, Ulrike Meinhof also stated that she is confident that the everything will clear itself up and that she will be reunited with her daughters. Personally, it seems to me that she is overly optimistic in that regard, for even if she should be fully cleared of any involvement in the Baader breakout, which is highly unlikely, her career as a journalist is almost certainly over. In fact, the TV station ARD immediately pulled Bambule, a TV movie Meinhof had written that was set to air on May 24, from its programming schedule.

The big question that remains is why. Why would a woman with two young daughters and a great career as a journalist, a woman who until recently was hobnobbing with the intellectual elite of West Germany, throw it all away to help break a convicted arsonist out of prison? We won't know for sure, unless Meinhof chooses to tell us, but there are some theories.

One theory is that Ulrike Meinhof suffered a mental breakdown. This is not as far-fetched as it might seem. Ulrike Meinhof had a troubled childhood. Her father died when she was six, her mother when she was fifteen. Moreover, in 1962, shortly after the birth of her twins, Meinhof was diagnosed with a brain tumour, though she eventually made a full recovery. Did the childhood trauma or her brain surgery cause lingering mental issues?

Another theory involves the central personage in this whole drama, Andreas Baader. As mentioned above, the 27-year-old Baader is very much a fringe figure in the West German leftwing scene and was a complete unknown until the Frankfurt arson attacks. In fact, people who knew him before said that he was a largely unpolitical failed artist, until he decided to set two department stores on fire. And while most members of the leftwing scene are academics, artists and intellectuals, Baader is a drifter, occasional drug dealer and car thief, who never even finished school. A lot of the people active in leftwing circles don't like him and say that he's a liar and a braggart desperate to impress and make his mark on the world. However, they also say that Baader is extremely charismatic and seems to exert an almost magnetic pull on women, though he himself prefers both genders equally.

Andreas Baader certainly bewitched Gudrun Ensslin, three years his senior, a graduate student of German literature and mother of a three-year-old son, to the point that Ensslin abandoned her young son, then only a baby, and broke up with his father to follow Baader into a life of crime like some latter day Bonnie and Clyde. And it's notable that most of the people involved in breaking Baader out of prison – Gudrun Ensslin, Ulrike Meinhof, Ingrid Schubert and Irene Goergens – are women. So did Ulrike Meinhof fall under Andreas Baader's spell as well?

Finally, those who know Ulrike Meinhof have said that she has been feeling increasingly frustrated with the political situation in West Germany and claimed that her journalistic work was only preaching to the converted, but did not help to bring about real change. Privately, Ulrike Meinhof also spoke of her desire to leave her hypocritical bourgeois life behind and engage in revolutionary activities to bring down the state. Whether those statements were genuine desires or follies born out of too much wine and marihuana, Ulrike Meinhof did in fact leave her normal life behind, when she jumped out of the window of the Central German Institute for Social Issues on May 14.

Aftermath

The question that most occupies West Germany right now is where are Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, Ulrike Meinhof, Horst Mahler, Ingrid Schubert, Irene Goergens and those who aided and abetted them. For so far, neither Andreas Baader nor any of those who helped to break him out of prison have resurfaced. In spite of an intense manhunt (and womanhunt), there is no trace of the fugitives. It is as if the ground itself swallowed them.

That said, there are whispers and rumours that many a prominent member of the West Berlin leftwing scene – people like writer and publisher Hans Magnus Enzensberger, actor and comedian Wolfgang Neuss, or actress Barbara Morawiecz – found the rather bedraggled fugitives on their doorstep, looking for a place to lie low, which suggests that they had no plan at all for what to do after breaking Baader out of prison. However, the former friends and comrades turned them away, especially once the full extent of what had happened became known. For even though leftwing activists can appear and sound radical at times, hardly any of them condone violence against human beings, especially against someone like janitor Georg Linke, a man who was just doing his job and had nothing whatsoever to do with anything. Nobody really wants the attention of the police or to get involved in one the biggest manhunts in recent German history, either.

Ulrike Meinhof Speaks Again

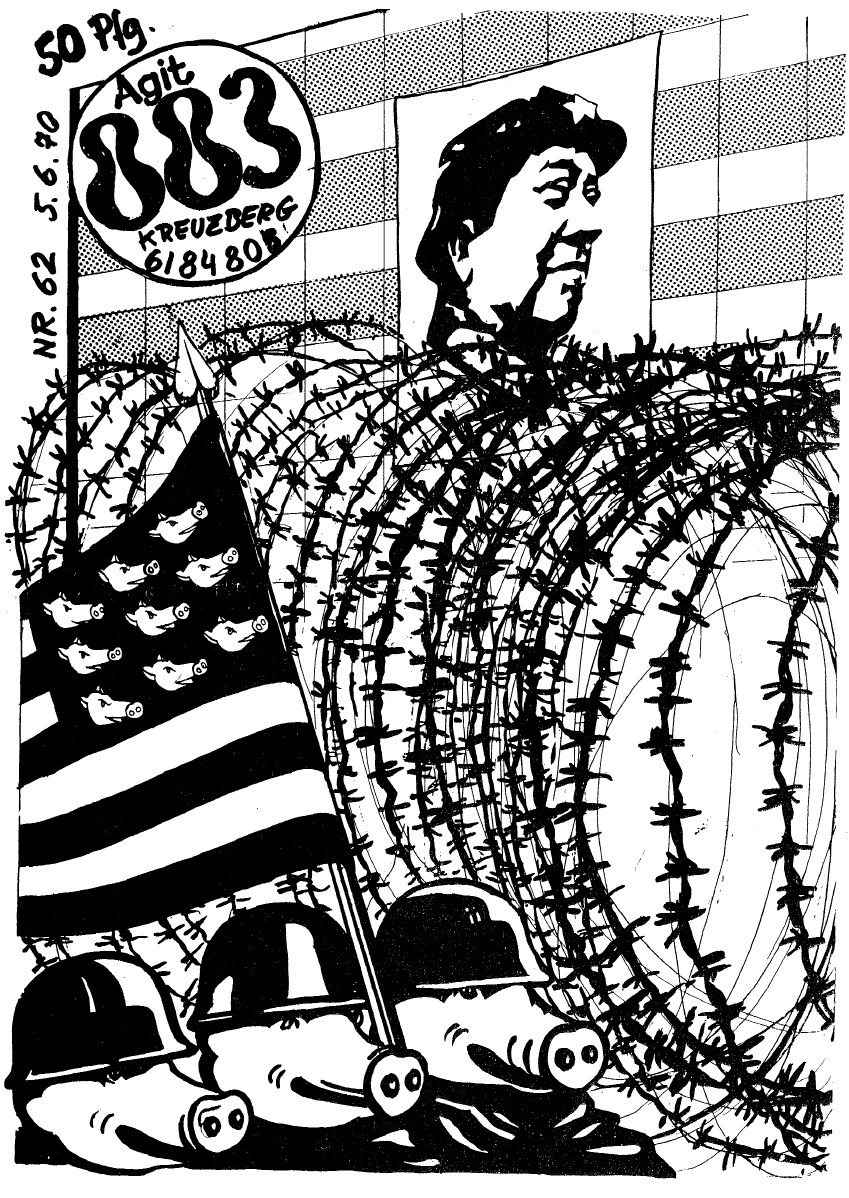

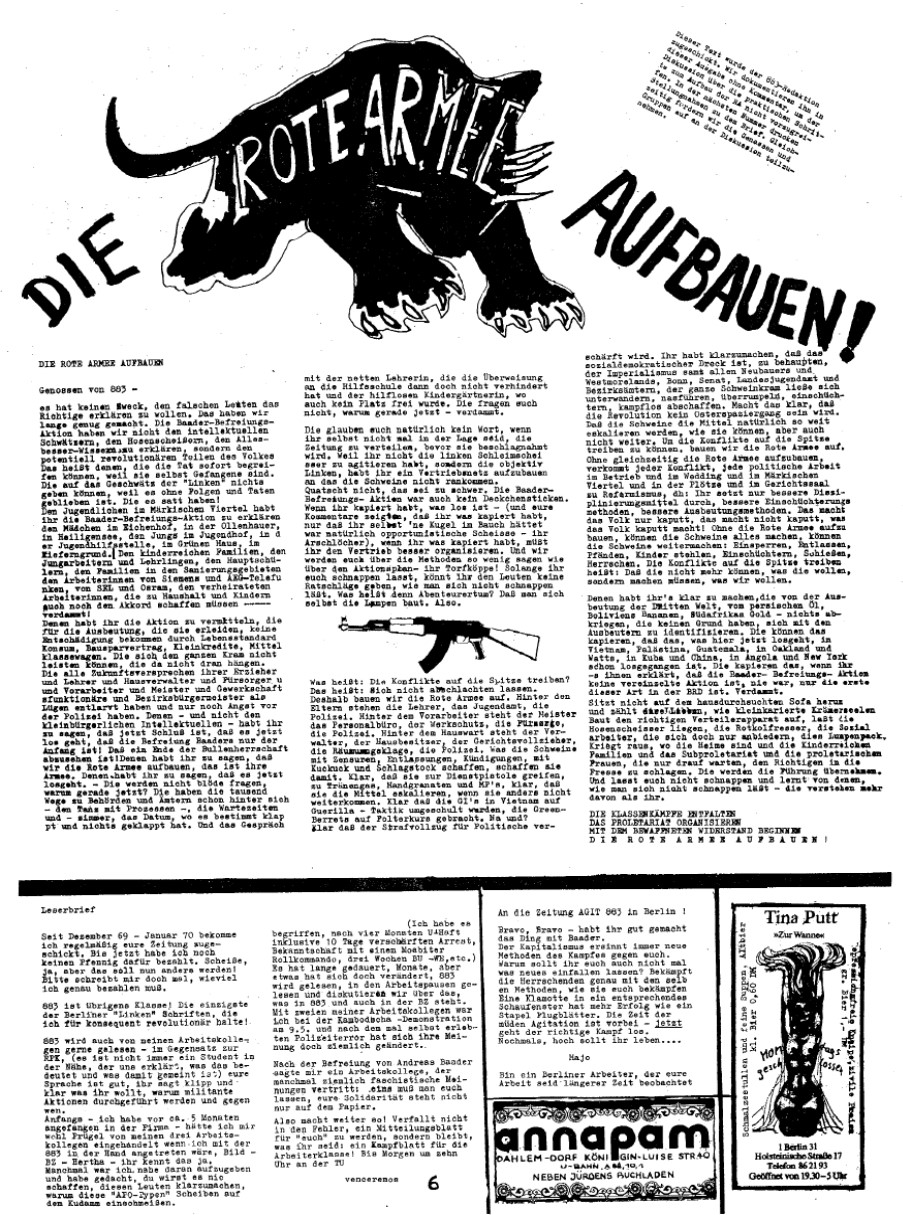

However, there have been some signs of life from the fugitives themselves. The first appeared on June 5 in issue 63 of the leftwing 'zine Agit 883, which had reported positively about the Baader breakout in a previous issue. It came in the form of a text entitled, "Building Up the Red Army". The article proclaimed that the break-out of Baader was only the beginning and that the rule of cops was about to come to an end. Furthermore, the article also denounced leftwing intellectuals as cowardly chatterers and instead declared that the revolution would come from below, from the working classes, from single mothers, from young people in homes for wayward youths. Police officers, civil servants, teachers, and social workers are referred to as pigs. There is no byline and the Agit 883 team claim to have received the text anonymously, but it's pretty obvious that the author is Ulrike Meinhof. Firstly, because she is the best writer among those who sprung Baader out of prison, secondly, because her style is quite distinctive, and thirdly, because the reference to homes for wayward youth and struggling single mothers refer to issues that are close to Meinhof's heart.

The text ends with the following words, typed in capital letters for extra emphasis:

INITIATE THE CLASS STRUGGLE

ORGANISE THE PROLETARIAT

START WITH ARMED RESISTANCE

BUILD THE RED ARMY

My first reaction upon reading this was, "Lots of luck, Charlie." For in spite of what Ulrike Meinhof and friends might believe, the working class is overwhelmingly on the side of the state in this matter and disgusted by the steadily escalating violence from parts of the left. Not that the working class reads the warmed over Marxism of Agit 883 anyway nor do they care about the fate of Andreas Baader. What is more, Georg Linke, the janitor who was shot while doing his job, is a member of the working class himself.

Agit 883 has a very limited distribution and most copies of the issue with the manifesto were seized by the West Berlin police anyway. So the next message from the fugitives appeared in a venue with a much wider reach. For the news magazine Der Spiegel received a tape recording by Ulrike Meinhof, delivered by the French model turned war correspondent Michèle Ray, who claimed to have met with Meinhof, Baader, Ensslin and Mahler in an apartment somewhere in West Berlin on June 5 and was handed the tape in question, which Der Spiegel chose to publish in their June 14 issue.

Once again, Meinhof denounces the intellectual left for being unwilling to take the next step and take up arms to bring about the revolution – I guess being turned away by former friends and allies really did hurt – and repeats that the working class, single mothers and wayward youths are the true intended recipients of the manifesto and that she hopes to build the Red Army. Once again, good luck with that, since the groups Meinhof is hoping to reach don't really read Der Spiegel either.

The manifesto also contains the following paragraph about how to respond to the police:

[…] Cops are pigs; we say, the guy in uniform is a pig, that's not a human being and we will have to treat them accordingly. That means, we do not have to talk to them and it's wrong to talk to these people at all, and of course shots can be fired.

This paragraph would be disturbing in any context, but it is even more disturbing coming from a woman who began her political activism in the peace movement.

Wrong Number

However, the most bizarre sign of life of fugitives came from a rather unlikely place, the Lebanese capital Beirut. Because on June 8, the French embassy in Beirut received a most unusual phone call from a man who introduced himself as lawyer Horst Mahler and started ranting about passports.

Apparently, Mahler had intended to call the East German embassy, but managed to call the French embassy instead. The French, who knew that Mahler was wanted in West Germany, immediately informed the Lebanese police to arrest the man and his companions.

It turned out that Mahler and a couple of others, including Ulrike Meinhof's boyfriend Peter Homann, had arrived in Beirut on a flight from East Berlin and intended to continue onwards to Jordan. However, their flight was cancelled due to an uprising in Jordan and so Mahler and his companions were stranded in Beirut. What was more, several members of the group did not have passports – honestly, did these would-be revolutionaries plan anything at all? – so Lebanese authorities confiscated everybody's passports, which prompted Mahler to call the embassy.

However, when the Lebanese police came to arrest Mahler and his companions at the airport, they were already gone, taken to a hotel in Beirut by members of a Palestinian militia group. The same Palestinians also repossessed the confiscated passports or rather the desk in which they had been locked up, because the Palestinians couldn't break open the drawer. The Lebanese police raided the hotel, but once again the fugitives were already gone, most likely to Jordan. The Lebanese authorities were also not overly interested in stopping them, because, "We have enough trouble in this country. We do not like to have additional trouble with these bastards."

This almost comical interlude does tell us where the fugitives went. Apparently, they made their way to East Berlin – and though the East German authorities are certainly aware that Horst Mahler and the rest are wanted in West Berlin, they have neither reason nor inclination to inform the West German authorities – and from there to the Middle East, most likely to join up with one of the various Palestinian militia groups operating in the region. In her manifesto, Ulrike Meinhof declared that their struggle is a global one and they were seeking to connect with various left wing movements such as the US Black Panther Party, the Vietcong, the Uruguayan Tupamaros, and the Palestinian liberation movement. I guess the other groups were harder to reach or not interested, so the Palestinians it was. Though it must also be noted that the group that arrived in Beirut on June 8 did not include Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, Ulrike Meinhof, Ingrid Schubert or Irene Goergens nor Ulrike Meinhof's young daughters. Their whereabouts are still unknown.

Knowing a little bit about the situation in the Middle East, I suspect that the West German radicals will not find the Palestinian militia pleasant bedfellows for long. Mostly likely, there will be a falling out sooner or later. And once the would-be revolutionaries return to West Germany, they will be arrested and they will go to prison. Which – to be honest – is what they deserve for breaking a convicted arsonist out of jail and critically wounding an innocent man in the process. Knowing how very little sympathy the West German justice system has even for non-violent leftwing activists, all of them are most likely looking at long prison sentences. And make no mistake, they brought this upon themselves.

My sympathies in this case lie squarely with Georg Linke, who will hopefully make a full recovery, and the two young daughters of Ulrike Meinhof who will hopefully be reunited with their father soon.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]