by Erica Frank

This episode opened with the Enterprise circling an uninhabitable lava planet with a poisonous atmosphere, but anomalous readings of some kind of civilization or power source. They planned to leave anyway, until they got a message…from Abraham Lincoln.

"Welcome to Washington, Captain Kirk!"

Our crew is now very experienced with meetings with aliens who seem to be people from history or mythology. Most of them wanted to call his bluff immediately, but Kirk played along: he wanted to find out what's happening.

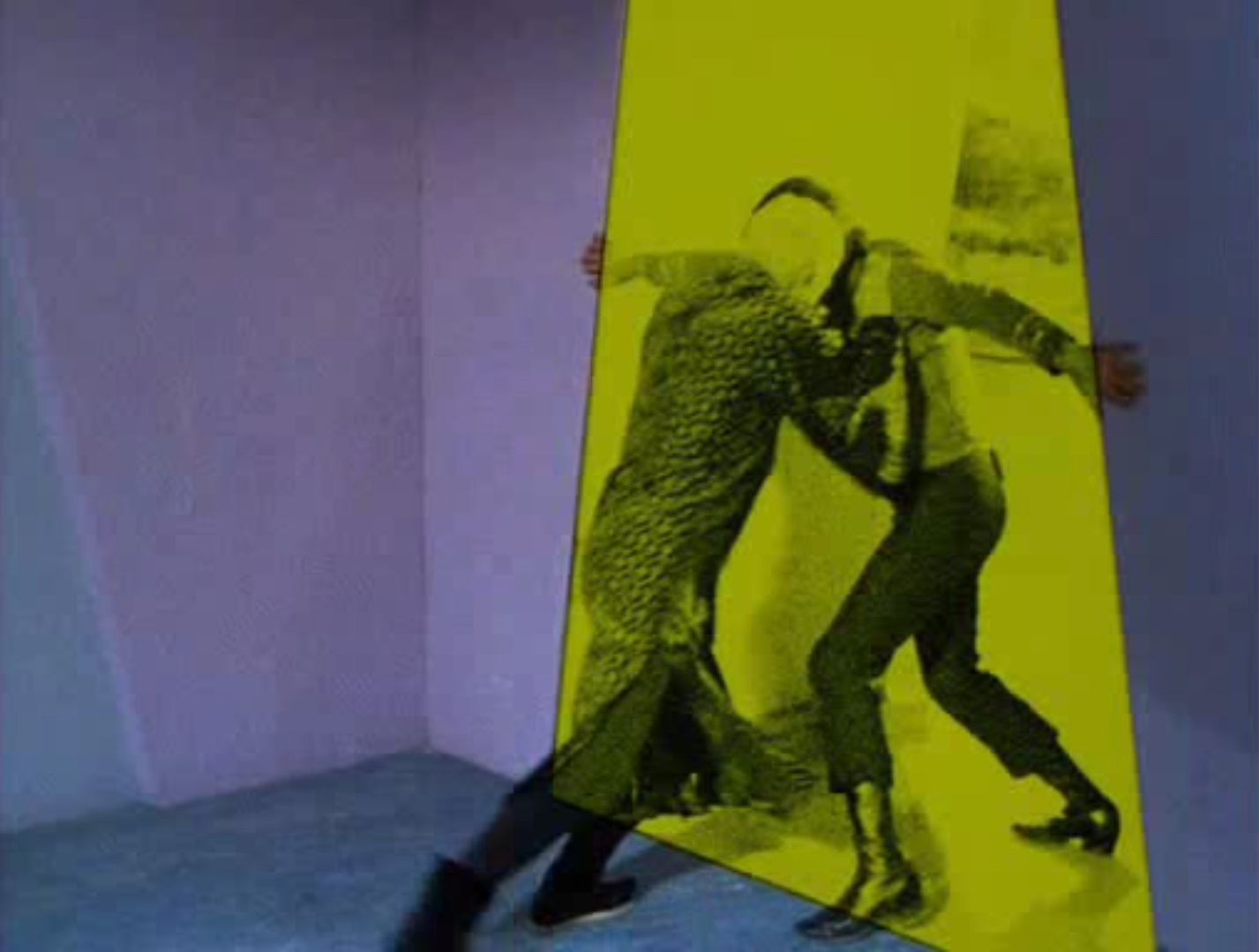

What's happening: A creature made of rock has decided to figure out what good and evil are by pitting four "good" heroes against four "evil" villains for the edification of its people.

Your host for the evening: an Excalbian rock creature that can read minds, terraform parts of a lava world, and shapeshift.

The Excalbian had arranged for Kirk and Spock—two people on the side of "good" (and the only living people involved)—to be joined by Abraham Lincoln, whom Kirk respects deeply, and Surak, the Vulcan philosopher who led the Vulcans out of war into their modern peaceful, logical society.

Abraham Lincoln dresses and speaks like a 19th-century statesman. Ancient Vulcan philosophers apparently dress and speak like the hippies who hang out at Haight & Ashbury in San Francisco today.

They were given opponents: Four of the worst villains from history (three of which we have never heard of before this episode)—two humans, one Klingon, and one other.

The Excalbians wished to "discover which is the stronger" of good or evil, and they had arranged what they call a "drama" with all the delicacy of a small child placing bugs in a jar and shaking it. In essence, "Here, we have put you all together and demanded you fight… whoever lives, that side must be the strongest."

As leverage to force the "good" side to fight, Kirk's crew would all be killed if he fails. The villains faced no such threats. Nor could they; whatever family or friends or honored associates they once had, none are alive today.

The villain line-up, from left to right: Genghis Khan, who needs (or at least gets) no introduction; Colonel Green, a genocidal war leader from 21st century Earth; Zora, a mad scientist from Tiburon; Kahless the Unforgettable, the Klingon tyrant.

At first, I wondered about the inclusion of Zora and Kahless: Is Klingon history so well-known to Kirk and Spock that the Excalbians can draw him from their minds? But the Federation and Klingons have been at odds for some time; they might well be familiar with their most famous historical figures. Zora seemed an outlier—until I remembered where I'd heard of Tiburon. It was the home of Dr. Sevrin, who led the quest for Planet Eden. (Apparently Tiburon has a history of unethical doctors.) Spock might well have known more about the planet's history.

The events that followed were annoyingly predictable. Green briefly attempted to negotiate, which was a distraction for an attack; the villains were driven off; Surak followed to speak to them, which resulted in his death; Lincoln tried to rescue him only to die as well; Kirk and Spock managed to defeat or drive off all four of the villains by themselves.

The Excalbian declared them the winners, but said he does not see any difference between their two philosophies. Kirk pointed out that he was fighting for the lives of his crew but the villains were fighting for personal power or glory. The Excalbian did not seem convinced, but sent them on their way, unharmed.

What was missing: Any mention that the value of "good" over "evil" is not shown on a battlefield, but in day-to-day living. That one strength of "good" is cooperation and shared resources—nearly irrelevant in a fabricated setting, with no time to develop tools, and a pre-selected pool of people who were chosen to play specific roles.

Colonel Green, the only white man on the "villain" team, watches from behind a rock while his companions fight for their lives. Maybe their lack of unity did matter.

I would have liked more consideration of the true nature of the six historical people: Just before they beamed "Lincoln" aboard the Enterprise, Spock said his readings were those of a "living rock" with claws. It seems likely that all the other people were Excalbians playing the part of historical characters. They were offered "power" if they won—but what would that mean? Would the other Excalbians hand them each spaceships and send them along to their respective planets? What could they possibly offer Genghis Khan?

Three stars. Interesting, but the pacing was odd (long, slow buildup to a couple of quick fight scenes), and I wanted more from both the philosophical and science fiction aspects.

Fair to Middlin’

by Janice L. Newman

Star Trek does like its ‘message’ episodes. Sometimes, as with "Day of the Dove or "The Enterprise Incident", the scriptwriter does a pretty good job of addressing the issues of the day. Other times, the scriptwriter does a poor or muddled job of Saying Something, as in "Let That Be Your Last Battlefield".

The Savage Curtain falls somewhere between these two extremes. Roddenberry had a couple of pretty clear messages he wanted to send: “violence can be justified if the cause is just” and “peace is an admirable goal, but one that takes time and sacrifice, and in the meantime sometimes violence is necessary”. It’s not surprising that the man who wrote (or re-wrote) “A Private Little War” would want to make these points. But in doing so, he missed the chance to make a much clearer distinction between ‘good’ and ‘evil’, one that would have served the story better.

The ‘evil’ characters in the episode showed an absolutely remarkable amount of teamwork. Colonel Green immediately took charge, and the others simply deferred to him and obeyed him. It stretched credibility just a little to see GHENGIS KHAN passively taking orders without so much as a peep of protest. In order to tell the exact story Roddenberry wanted to tell, characters that should have been backstabbing each other to get ahead or refusing to work together at all instead acted as a well-oiled unit. They had to trust each other, support each other, and listen to each other. In fact, the ‘evil’ characters had to act a little bit good. (While the ‘good’ characters in turn had to commit violence to make the story work, necessitating that they behave in an ‘evil’ way.)

How much more effective could it have been if the ‘evil’ characters had actually behaved in a selfish, anti-social, backbiting manner, and were defeated by people who worked together for the common good? How much more powerful could the message have been if the ‘good’ side found a solution that wasn’t based in violence, using teamwork, cleverness, and the combination of their knowledge and skills?

Maybe it would have been trite, but the idea of good and evil being absolutes is pretty trite, too.

The bit with Uhura explaining that race relations had progressed so far that words were no big deal was nice, though.

Three stars.

By What Right

by Mx. Blue Cathey-Thiele

In an episode that gave us Abraham Lincoln in space, cultural figures from Klingon and Vulcan history, and an amazing alien design, the thing that I kept thinking about after the episode was this:

KIRK: “How many others have you done this to? What gives you the right to hand out life and death?”

ROCK: “The same right that brought you here. The need to know new things.”

The question has been posed before. What right does Starfleet have? As early as season one, in "The Naked Time", a crewman despaired over humanity polluting space and sticking their noses where they “didn't belong”. His distress was exaggerated by an alien liquid, but the question was real. Is the crew—or Starfleet at large—doing harm in their quest for knowledge? The first directive shows that there has been significant thought on this, instructing Kirk not to infringe on cultures and to make repairs when possible if there has been a violation of the directive. It's an imperfect rule, and one that is broken frequently. Kirk or another officer decides that he knows better, or finds a reason why the directive doesn’t apply. There have been times when that directive hampers life-saving action.

The Excalabian’s actions are cruel by human standards, and as a means to understand the philosophy of “good vs. evil” make no sense to me. But that itself works as a mirror. I have no insight into the alien mind, no way to know what metric it judges by, no concept of how it views humans in relationship to itself. Equal beings? The way humans might regard a very clever animal? Insects under a microscope? Maybe even the way humans view other humans that fall outside their range of “people”.

This amoral broadcast brought to you in living color on NBC!

Human history is full of examples of people seeking knowledge and trampling over others to get it. The many places considered “untouched” on Earth that already have inhabitants, lands reshaped and mined for resources, animals hunted to extinction. The victims of experiments done under the guise of “progress”, psychological and physical studies done without permission, or care for the comfort or pain of the subjected person. Plenty of this has been done deliberately, but lack of ill-intent doesn't change the consequences either. As astronauts practice maneuvers in space, it is important for us, now, to remember that everything leaves a trace. The moon is a remarkable example, but hardly the only one. Just because we can doesn't mean we should – and yet, humans have a place in the universe too, and knowledge is part of that.

The question is not one with an easy answer, and might not have a correct answer. I think it is a question we should not stop asking though, because if we stop, that is when we have decided that yes we *do* know better, and stop caring what, or who gets hurt.

Even with all that philosophy, the episode still felt much like re-do of Kirk fighting the Gorn Captain in Arena, with more puzzling pieces than actual interesting plot.

2 stars

Truly Alien

by Joe Reid

“The Savage Curtain" was something unique. We have witnessed previous episodes where alien races test humans to see if they are honorable, or understand empathy, or if they are worthy of something. This week we had an alien race that wished to weigh the concepts of good and evil by playing the parts of the noble and of the wicked themselves; instead of seeking to understand something conceptually, they chose to understand experientially. Coupled with the inhumanity of their physical appearance, they were the most alien aliens that we have seen in a very long time from this show.

If I wished to understand women better, what options would be available to me? I suppose that I could talk to a woman to learn about them. I could go to my local library and borrow a few books about women. Hell, I could even watch women to attempt to learn about them through observation. I don’t have the ability nor would choose to become a woman and fully live as one merely to satisfy my curiosity. Excuse that poor and possibly male-chauvinistic example.

Let’s say I wanted to understand Phantom Limb Syndrome. That is the sensations that amputees experience from limbs that are no longer there. It would be impossible for me to truly understand what it is like without experiencing it. My point being that who would be willing to go through dismemberment to experientially understand something? Although through grave misfortune we could experience such a thing, we would experience it as ourselves. The Excalbians had the ability to learn by becoming who they were not. The very concept is alien.

"Don't look so stone-faced, Captain. Haha. That's an alien joke."

Walking a mile in another man’s shoe is one thing, walking with another man’s legs is entirely different. As novel as this ability of the Excalbians is, what’s more interesting and alien is the lack of judgment they had against the concepts of good and evil. It was as if these creatures never ate from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil as humanity had in the story from the book of Genesis. How would beings such as the Excalbians gain that knowledge? Kirk and crew had a clear sense of right and wrong, the Excalbians seemed to not only lack it, but also held no bias of one over the other. Kirk apparently came to the same conclusion. As the Enterprise left Excalbia at the end of the episode, the crew cast no negative aspersions against the Excalbians for their lack of understanding. They were aliens and they got what they were after. Thankfully no one died.

In this episode the crew clearly found a new lifeform and new civilization. This one being a powerful yet innocent race of aliens whose reasoning is far removed from human rationale. They were refreshingly different and a welcomed change to the way that aliens are usually presented, as humans with some greasepaint.

4 stars

Eclipse Glasses for War

by Jessica Dickinson Goodman

On September 11th of this year, people on the west coast of America will see most of a solar eclipse. Adults who are smart or at least a little prepared will be viewing it through special eclipse sunglasses. Those of us with small children will be building cardboard boxes with pinholes in them, since there’s nearly nothing as futile as putting unwanted sunglasses on a toddler.

The boxes work like this: you pick a box big enough for both of your heads — like a home television box — and poke a round hole in it. When the appointed time to look comes, you put the box on your heads with the pinhole behind your right shoulder, aim the pinhole at the sun, and look the other way. The shadow of the earth will then creep across that perfect bright dot beaming onto the opposite wall of the box, allowing you and your child to track its progress without risking young eyes.

The dark box is a child’s version of Plato’s Cave, allowing us to safely view astronomical truths too large and too bright to safely see with the naked soul. It is also a bit like going to the movies: the appointed time, the rising tension, peak, and denouement, the use of light and darkness to tell a story. Most important to the experience is both the smallness and safety of it and of us: the sun is no more in that box than we are on its surface, but viewing it so allows us access to realities we could not otherwise safely imbibe.

That’s how I think of Star Trek’s suite of war analogy episodes, thoughtfully listed by Erica in the head article. The daily truth of America’s war on Vietnam involves numbers so astronomical, forms of violence so molten and charring, it is difficult to look directly at, much less explain to a child. But there are some dimensions of the conflict which can be conveyed in an episode like this, just as that pinhole box can convey the sun’s roundness, brightness, the semi-circular shape of earth’s intruding and then receding shadow, and the emotional excitement of having a Mama put a funny box over your head for 45 minutes during playtime. Likewise, this episode gave us some shapes from the war: the torture of POWs becomes Sarek’s simulated cries over the hilltop; the horror of punji sticks embedded in the darkling trails of the jungle become stakes carved and thrown by the characters. And tens of thousands of soldiers become four against four; brutal still, yes, but grokable. We don’t have Lodges and Westmorelands, Ho Chi Mins and Mao Tse-Tungs, but we can see the flickers of them in the shadows on the wall.

A poor man's Hanoi Hilton

Maybe you didn’t see this week’s episode as an allegory for Vietnam, but remember, we too are in the box or the cave, and what we bring with us affects what we see there. I see punji sticks and you may see the Bataan Death March. I see POWs and you may see a lynched man. But this episode gives space for us to approach different forms of violence and peace, evil and good, as and when we need to.

One way it does this is with the abject silliness of seeing Abraham Lincoln in space, shipless and fancy free. See, the episode seems to say, nothing is real here; this is just a silly sci fi show. But that is part of the box too and of the cave. The silliness of joining a new context shakes us free of our old one and allows us to see the dot on the wall, its roundness, its brightness, and the exact geometries of its transfiguration in a way we could never see the sun directly. The disgust I felt for the rock monster treating our beloved crew as chess pieces and bargaining chips only lightly touched on the incandescent rage I feel towards the Westmorelands and Maos of the world—playing greater power games as children die bloody. But it did allow me to touch it, to engage with it, to see it as small enough to understand the shape of it for once rather than be overwhelmed and blinded by its light.

This was not a good episode, as detailed above. The dialogue and morals were cloudy and at times crudely wrought. But as one in a series of episodes touching on different aspects of our nation’s current war, it did what it was supposed to: give us 48 minutes in the dark and the quiet to think about things we might not otherwise have been able to, see the shape and changing ways of them, and come out of it having touched something far beyond our reach.

Three stars.

[Come join us tomorrow (March 13th) for the next thrilling episode of Star Trek! KGJ is broadcasting the show live with commercials and accompanied by trekzine readings at 8pm Eastern and Pacific. You won't want to miss it…]

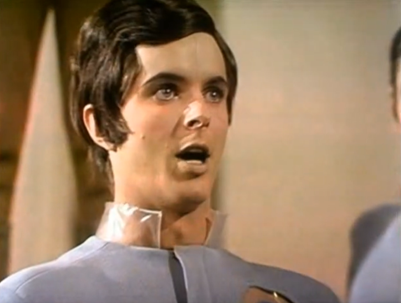

![[May 18, 1969] Whirr Hum Bang Bang (Doctor Who: The War Games [Parts 1-4])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/690518deathsentence-672x372.jpg)

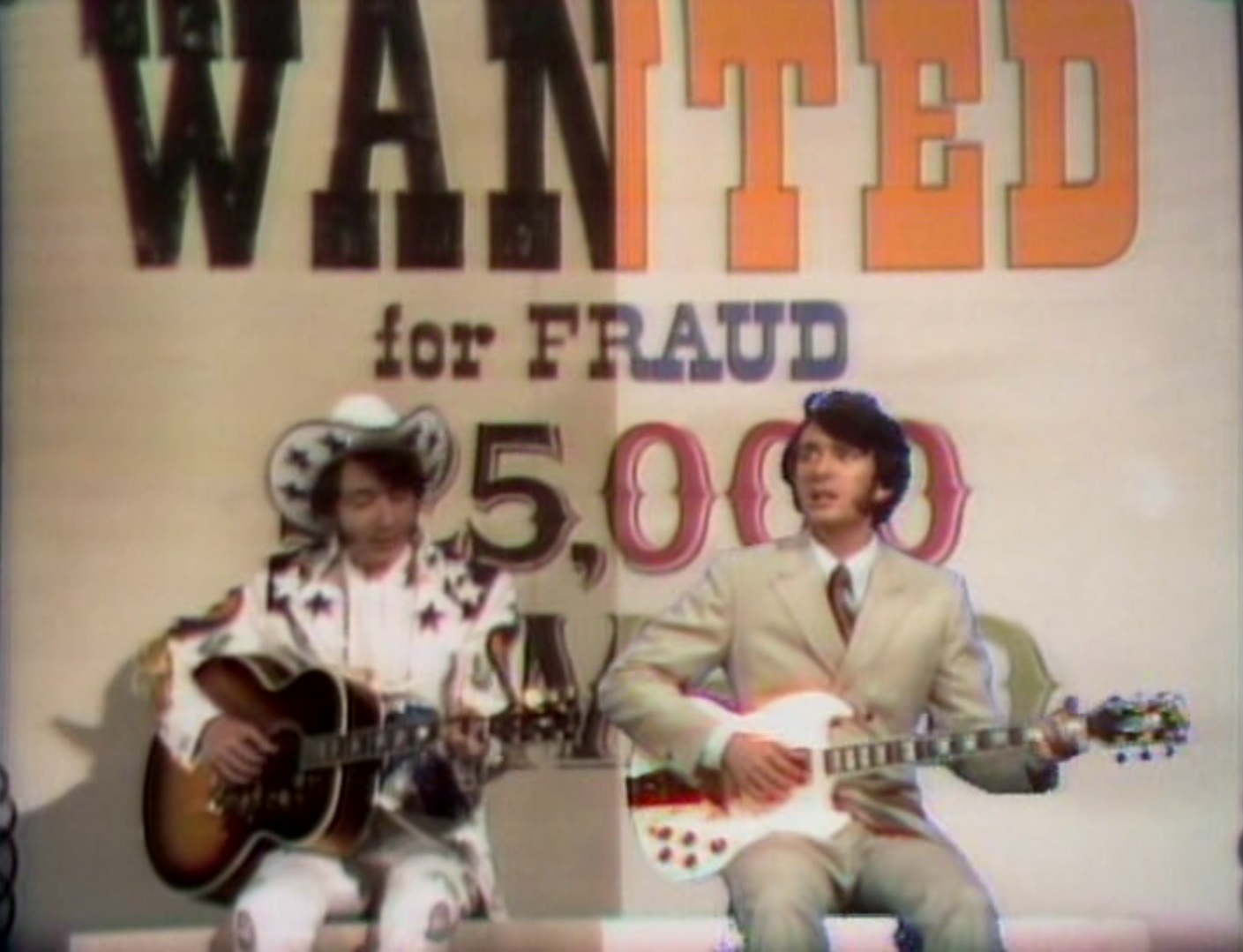

![[May 8, 1969] Cooked in the Chrysalis (The Monkees TV special: <i>33 1/3 Revolutions Per Monkee</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/690508tubes-672x372.jpg)

![[May 4, 1969] Navigating the Wasteland #3 (1966-69 in (good) television)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690504laughin-672x372.jpg)

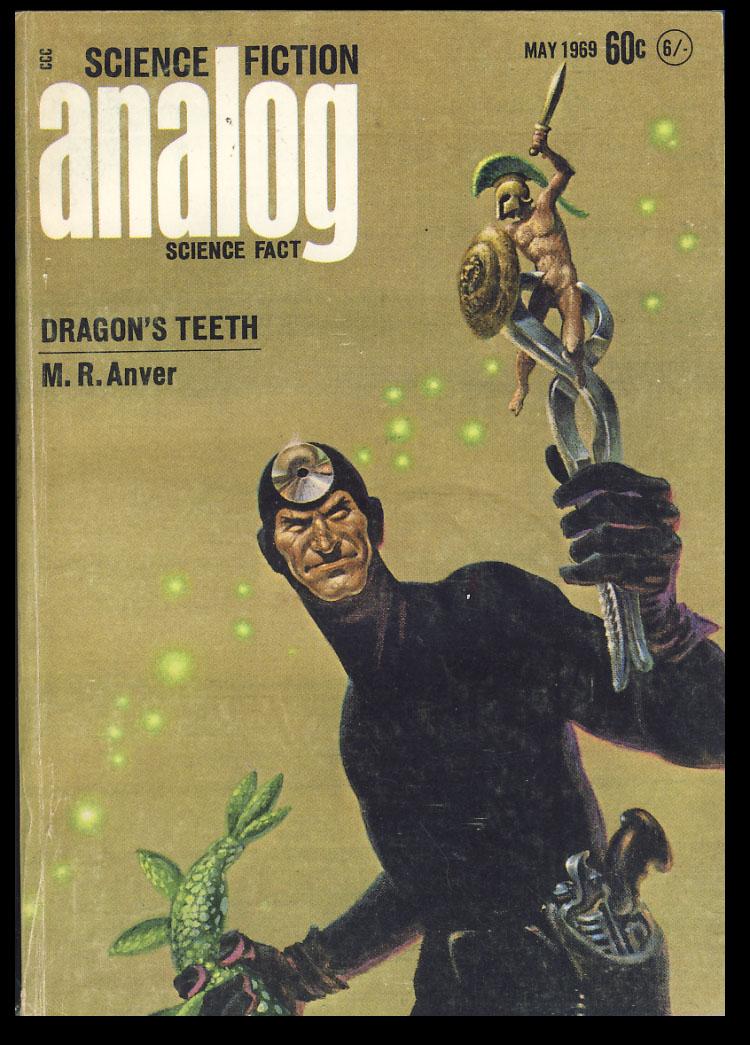

![[April 30, 1969] Eulogies (May 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690430analogcover-672x372.jpg)

![[April 14, 1969] My Least Favourite Kind Of Cereal (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Space Pirates [Parts 4-6])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690414justuseyourimagination-672x372.jpg)

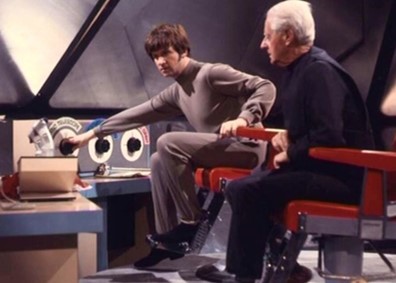

![[April 2, 1969] A New Beginning? (Out of the Unknown: Season Three)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Picture3.jpg)

![[March 26, 1969] Avast, Ye Scurvy Dogs! (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Space Pirates [Parts 1-3])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/690326thisiswhyiama2jaimieenthusiast-672x372.jpg)

![[March 18, 1969] What a way to go! (<i>Star Trek</i>: "All Our Yesterdays")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/690318title-672x372.jpg)

![[March 12, 1969] Rock Opera (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The Savage Curtain")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/690312curtain-672x372.jpg)

![[March 6, 1969] Different points of view (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The Cloud Minders")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/690306title1-672x372.jpg)