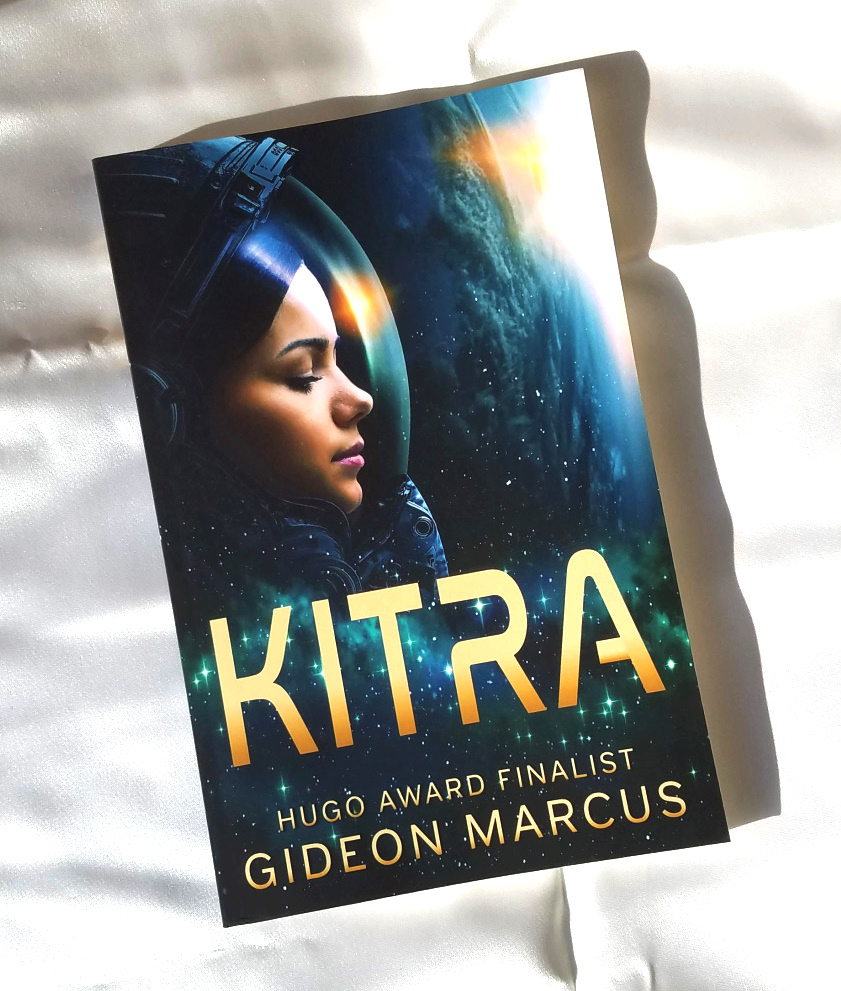

[This month's first Galactoscope features an esteemed pair of science fiction novels. The first is by one of the genre's most accomplished veterans, the other by one of its newest and brightest lights…]

by Gideon Marcus

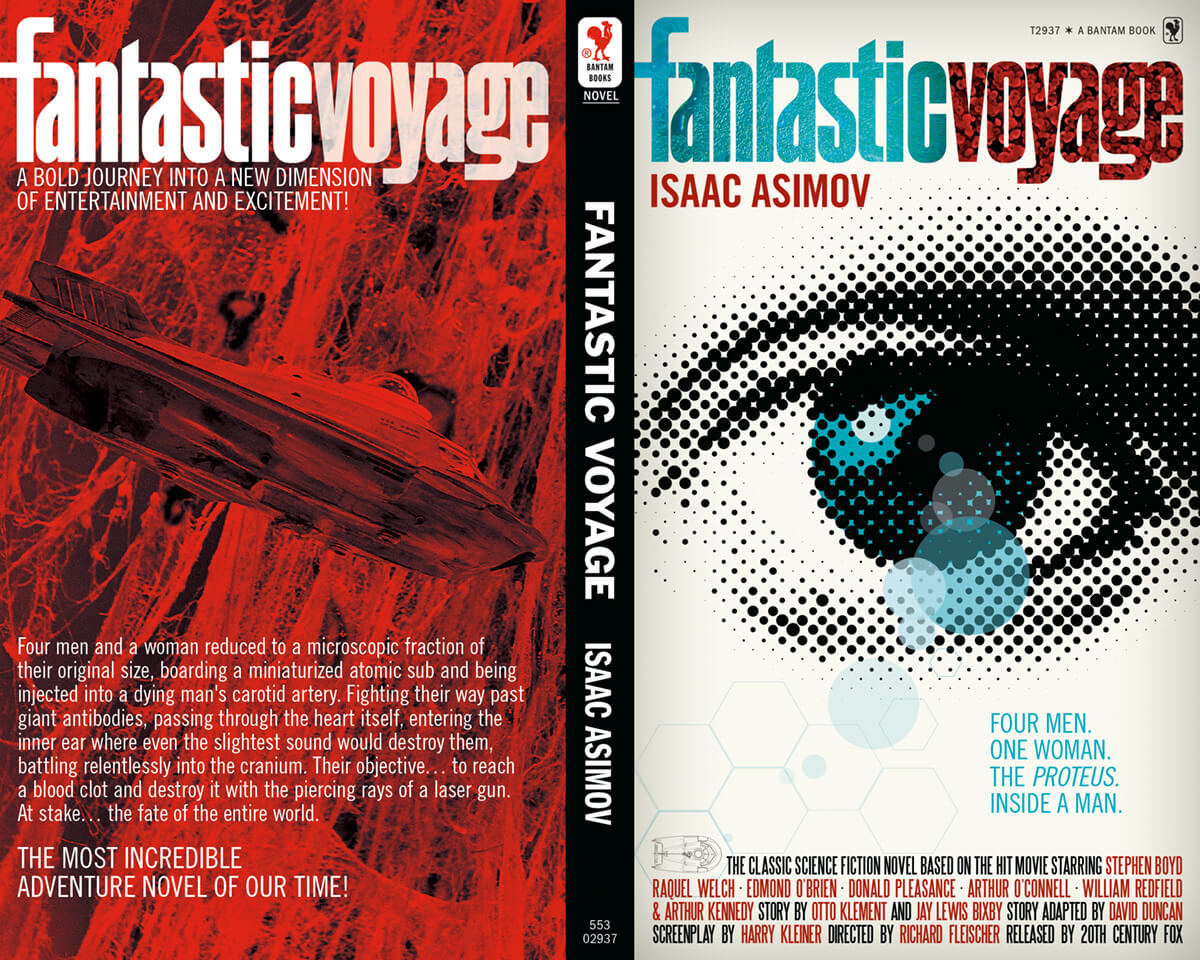

Fantastic Voyage, by Isaac Asimov

A defector from beyond the Iron Curtain lies dying on the operating table, a terrible secret in his brain. Only an operation from the inside has any chance of success. Thus begins a fantastic voyage in which five souls in a midget submarine are miniaturized and injected into the patient. Their destination: the blood clot that threatens the defecting scientist's mind.

A myriad of biological wonders and horrors awaits the team, from antibodies to circulatory typhoons. But even more dangerous to the mission is the possibility of a saboteur on board. Is it Owens, pilot and designer of the Proteus? Duval, the brilliant but antisocial surgeon? His expert laser technician assistant, Peterson? The cartographer of the circulatory system, Michaels? Or could it be Grant, the agent dispatched to watch the other four?

And can the saboteur be stopped before the miniaturization wears off, killing the patient and potentially the crew?

Voyage marks the author's return to novel-length fiction after a nearly a decade. The circumstances are unusual; I understand the book is actually a novelization of a movie script, though unusually, the movie is not due out for many months. Dr. A is, of course, a great choice for the job. With his chemistry and general scientific background, he renders just plausible what will likely be enjoyable folderol on the screen. He combines a vivid depiction of the inside of the human body with his usual competent pacing and plotting. And as an old hand at mysteries (he essentially invented the still meager science fiction/mystery hybrid genre), he does a good job turning a science fiction adventure into a whodunnit.

I suspect what I don't like about the book mostly derives from the original script. I found a lot of the action sequences a bit tedious. Frankly, I might have been happier with a book that was just a guided tour of the human body from within, so deft is the Good Doctor with his nonfiction writing. I also found Grant's incessant pursuit of Ms. Peterson (first name, Cora, like our esteemed fellow traveler) annoying — just let her do her job, man! Also, only two thirds of the book are devoted to the actual voyage, insertion not taking place until page 70. The build-up to the action feels a bit drawn out.

Nevertheless, it's a fine book and it's great to see Asimov flexing his fictional muscles again.

Three and a half stars.

Empire Star, by Samuel R. Delany

by John Boston

Samuel R. Delany has been quietly pumping out Ace paperbacks for a while, building a reputation from the bottom up. He’s up to six now with the newest, Empire Star, and I thought I’d better pay some attention.

by Jack Gaughan

Empire Star is your basic unprepossessing—actually, pretty ugly—half of an Ace Double, just under 100 pages, with generically goofy blurb: "He warped time and space to deliver a message to eternity." But open it up and it features epigraphs from Proust and W.H. Auden (a first for Ace, I'm sure), and then introduces us to Comet Jo. What? Is this the new Captain Future?

Fortunately not. Comet Jo is a yokel, galactically speaking, living on a satellite (of what, it’s not clear) in the Tau Ceti system. He’s physically graceful, with claws on one hand, and his hair is long and either wheat-colored or yellow depending on which paragraph you’re reading. He carries an ocarina wherever he goes. He works tending the underground fields of plyasil, more crudely known as jhup, “an organic plastic that grows in the flower of a mutant strain of grain that only blooms with the radiation that comes from the heart of Rhys in the darkness of the caves.” He got his nickname wandering away from home to look at the stars.

One day Comet Jo hears a menacing noise, sees a devil-kitten (eight legs, three horns, hisses when upset) which leads him to where “green slop frothed and flamed,” with writhing, dying figures visible in it. One of them breaks out—Comet Jo’s double—and tells him he needs to take a message to Empire Star, but dies before he can say what the message is. The kitten rescues a small object from the now-cooled and evaporating puddle. This is Jewel—“multicolored, multifaceted, multiplexed, and me”—i.e., the narrator, who we later learn is a “crystallized Tritovian.” Say what? High-powered miniature computer with a personality—at least that will do.

So Comet Jo (hereinafter denominated “CJ”) goes to the spaceport the next morning to head for Empire Star, which he knows nothing about, to deliver a message he doesn’t have. This farmhand gets hired on the spot to work on a spaceship, no questions asked. On the way he encounters the strikingly dressed San Severina, who tells him he’s a beautiful boy but he needs to comb his hair, gives him a comb, and offers him diction lessons. She proves to be the owner of the ship he’s working on, and of the seven Lll aboard—sentient slaves who are great builders and project their emotions of great sadness to anyone who gets close to them. Owning these slaves is not a lot of fun.

Why not free them? “Economics.” San Severina explains that after a war she has “eight worlds, fifty-two civilizations, and thirty-two thousand three hundred and fifty-seven complete and distinct ethical systems to rebuild,” and can’t do it without the enslaved Lll. She also tells CJ he has a long journey ahead and has a message to deliver quite precisely. How she knows this is not explained, and CJ still doesn’t know what the message is. This is one of many incidents in which the people CJ encounters seem to know more about his mission than he does.

During these events, and later, CJ is told that he and his culture are simplex, as opposed to complex and multiplex, terms which are tossed around throughout the book without being defined very precisely. (Where is A.E. van Vogt when you need him? Never mind, forget I said it.) We are told that multiplex means being able to see things from different points of view, and also it seems to have something to do with pattern recognition. Also the multiplex ask questions when they need to. It certainly means becoming more mentally capable. A big part of the story is CJ’s getting more plexy with experience.

San Severina leaves him on Earth on his own, but advises him to “find the Lump.” Say what? Only clue is it’s “not a people.” The Lump—which turns out to be a linguistic ubiquitous multi-plex, also part Lll, in the guise of a portly man named Oscar—finds him. They set out in separate spaceships, but CJ quickly bumps into something—the Geodetic Survey Station, whose occupants are up to volume 167, Bba to Bbaab—and narrowly escapes the wrath of a comical and homicidal pedant. At their destination, in orbit around the inhospitable planet Tantamount, CJ and Oscar encounter the poet Ni Ty Lee, who discloses that he worked on Rhys in the jhup fields before, and also played the ocarina once, which mightily disturbs CJ, and leads into a disquisition by the Lump on the works of Theodore Sturgeon, four thousand years gone by the time of the story. Ni Ty Lee discloses more things he has done before CJ, including hanging out with San Severina, and CJ gets even more upset. Ni isn’t happy either; he exclaims, “Always returning, always coming back, always the same things over and over and over!” Hint, in neon!

Enough synopsis. The book continues in similar style. It should be clear by now that large parts of this story make very little sense, starting with CJ’s determination to leave his farm job and head for the galactic capital with a yet-nonexistent message, because he was told to do so under the most bizarre and alarming circumstances. But that’s OK because it’s not really a story in the usual sense. Rather, it’s a story about a story, or about Story, or about the author moving game pieces about a board, each piece decorated with a piece of the stock imagery of pulp SF. (Towards the end there’s even a Prince leading a spaceborne army to take over Empire Star, and the heiress to the throne struggling to thwart him.) Maybe it’s better described as a confection. There is of course a revelation at the end that purports to rationalize everything, and does to some extent, but it’s almost beside the point.

My patience for this sort of construct is generally limited, but Empire Star is extremely well done. It’s enormously clever, with many pleasing and colorful displays along the way; there’s much more detail and incident than the foregoing half-synopsis hints, even if much remains unexplained or implausible. Enormous cleverness colorfully rendered is never to be sneezed at. Four stars.

[Note: We will have to read Tom Purdom's The Tree Lord of Imeton to finish this Ace Double, and also because, well, it's Tom Purdom! Stay tuned…(ed.)]

The Journey is once again up for a Best Fanzine Hugo nomination — and its founder is up for several other awards as well! If you've got a Worldcon membership, or if you just want to see what Gideon's done that's Hugo-worthy, please read his Hugo Eligibility article! Thank you for your continued support.

![[February 10, 1966] Within and without (Isaac Asimov's <i>Fantastic Voyage</i> and Samuel R. Delany's <i>Empire Star</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/660210cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 28, 1966] The Book as Rorschach Test (<i>Flowers for Algernon</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/laboratory-mouse-a55d9736-9685-4f2a-b530-192cdc8ee6a-resize-750-672x372.jpg)

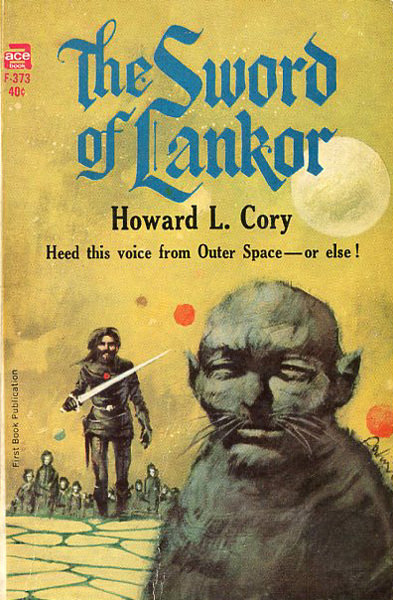

![[January 22, 1966] Monks, Demi-Gods and Cat People: <i>The Sword of Lankor</i> by Howard L. Cory](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/SWRDLNKR1966-393x372.jpg)

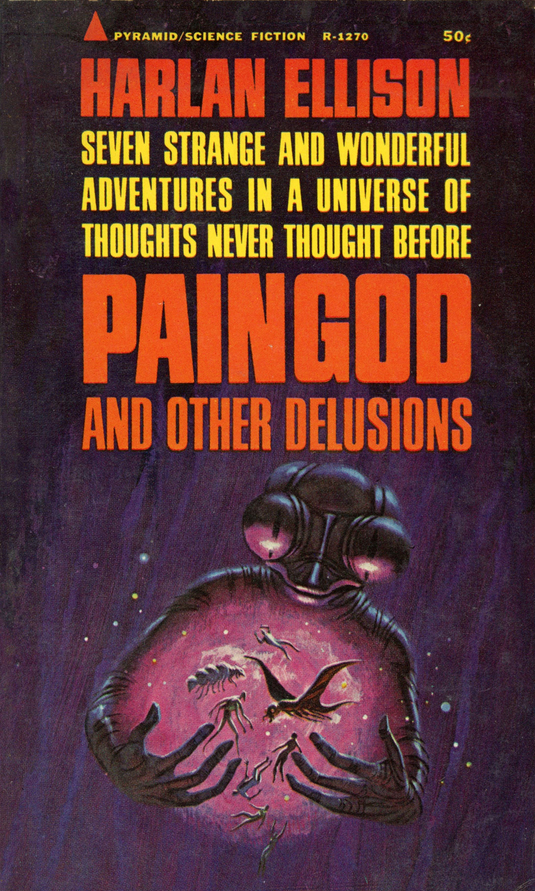

![[December 24, 1965] Gallimaufry <i>du Saison</i>(<i>The Year's best Science Fiction</i> and <i>Paingod and Other Delusions</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/651224covers-672x372.jpg)

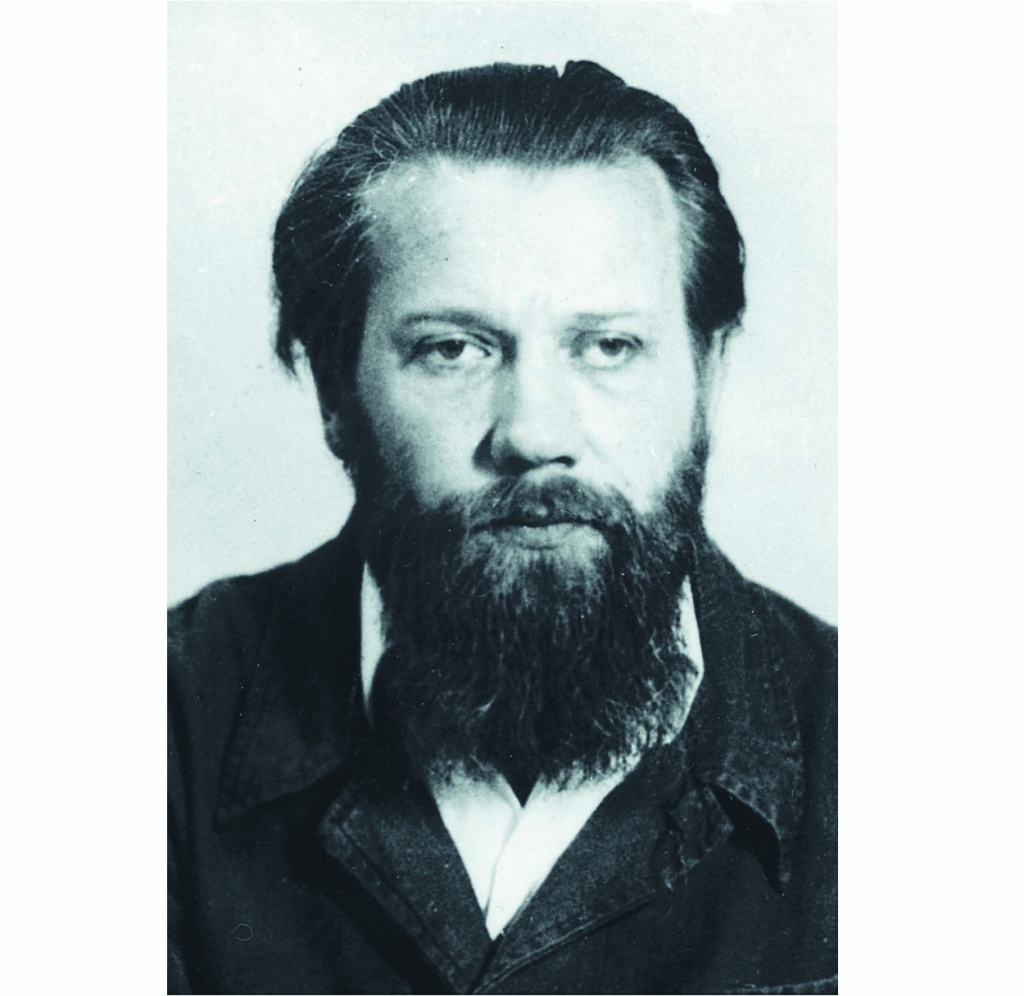

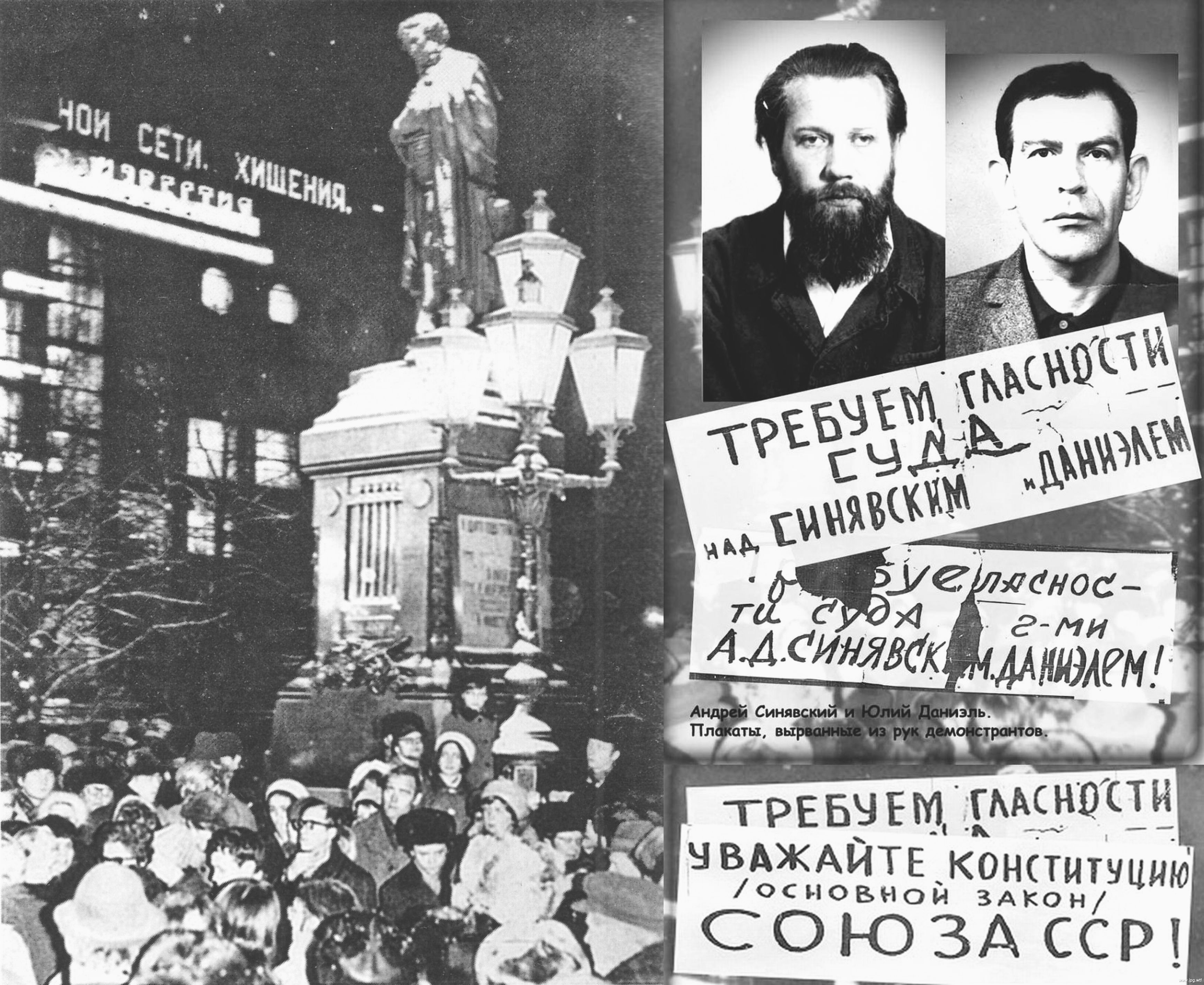

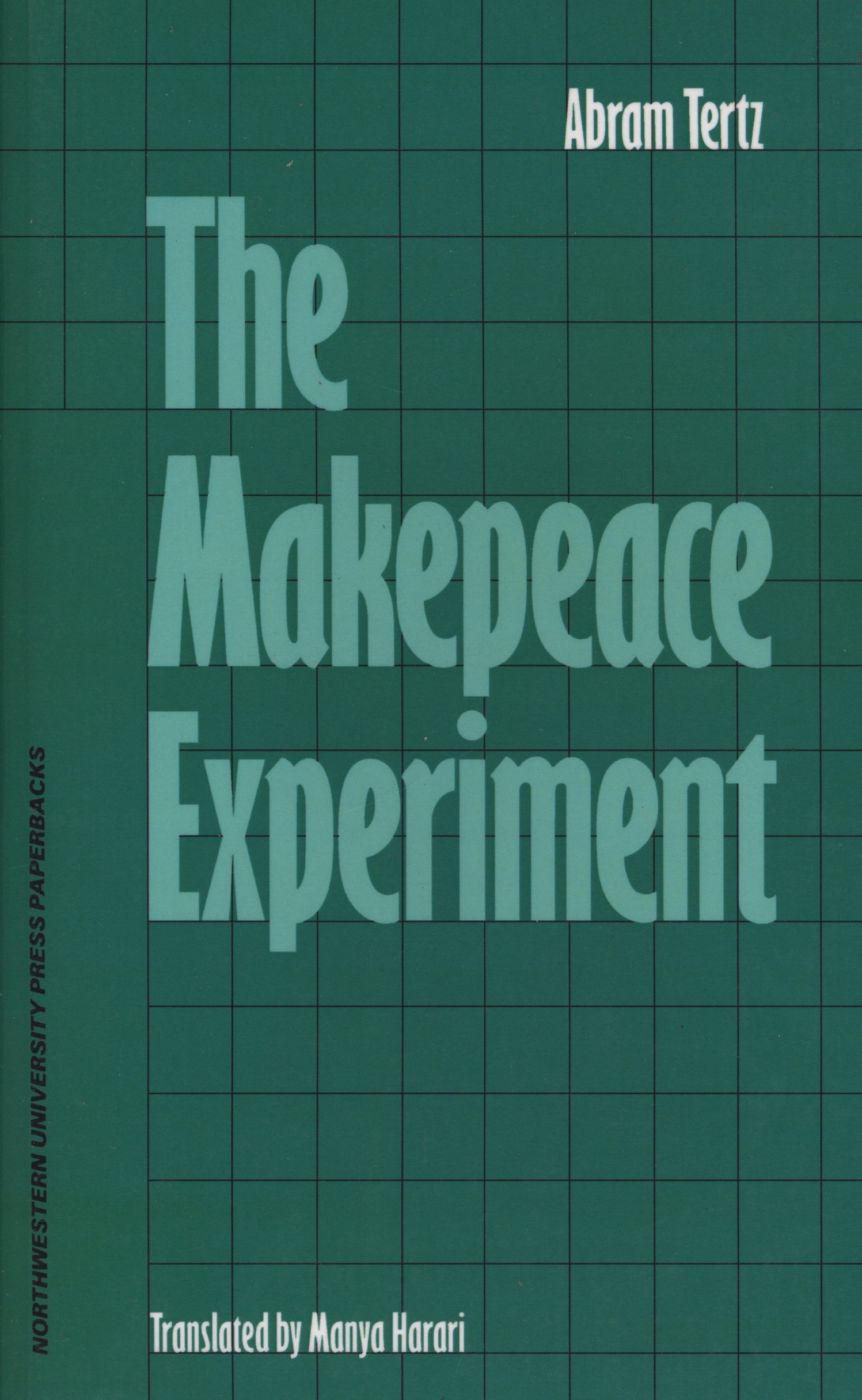

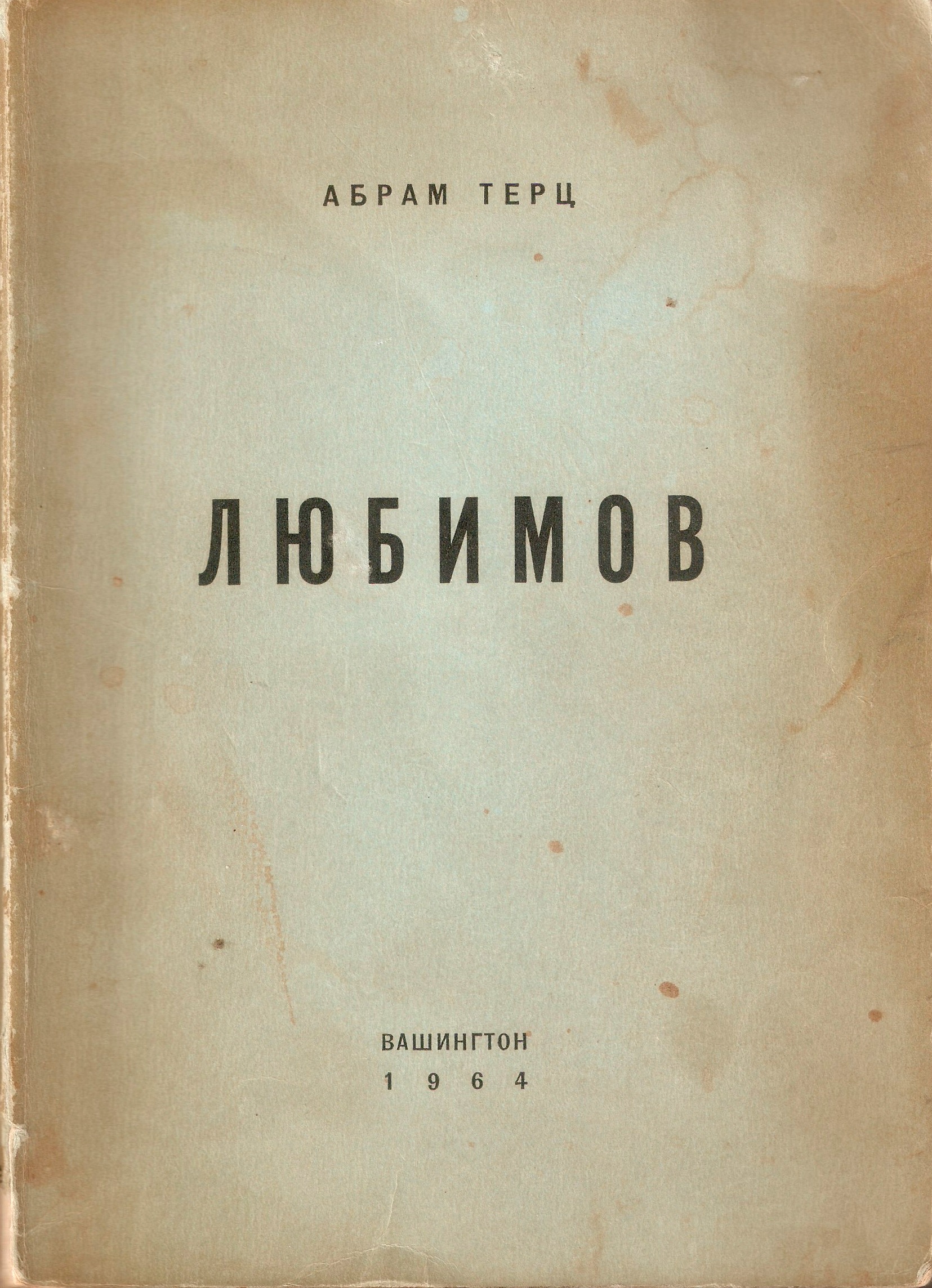

![[December 10, 1965] For the People, By the People <i>The Makepeace Experiment</i>, by Andrei Sinyavsky](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/651218Makepeace-Experiment-672x372.jpg)

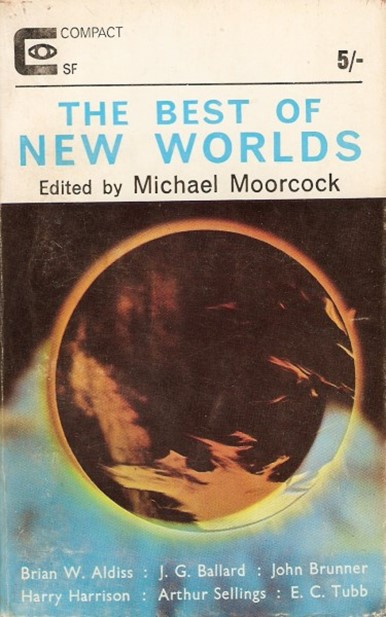

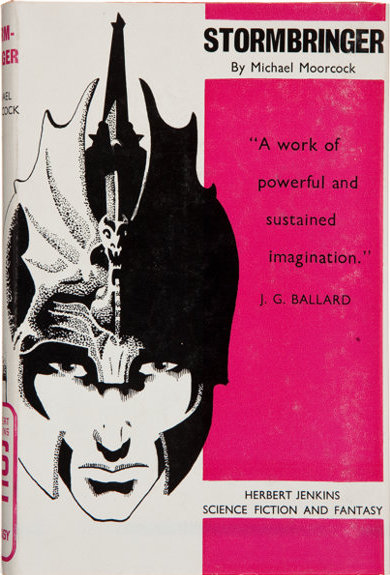

![[December 4, 1965] A Sign of the Times (Michael Moorcock’s Books of 1965)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Michael-Moorcock-672x372.jpg)

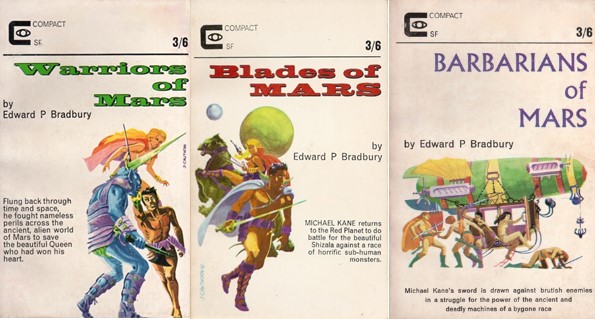

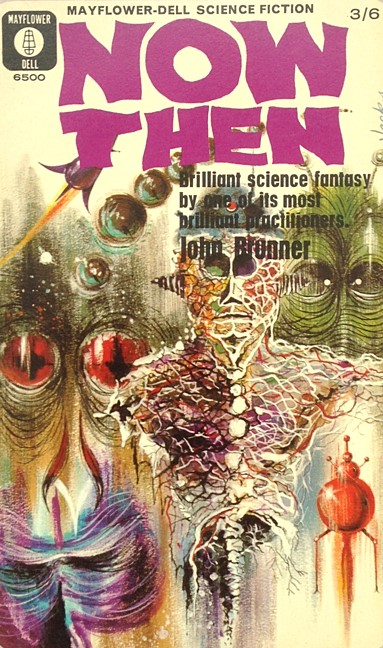

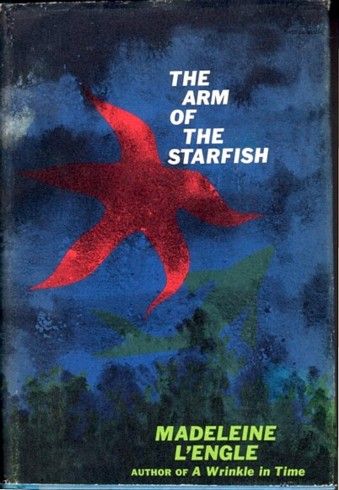

![[November 24, 1965] Books from Old Blighty (November Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/651124covers-672x372.jpg)

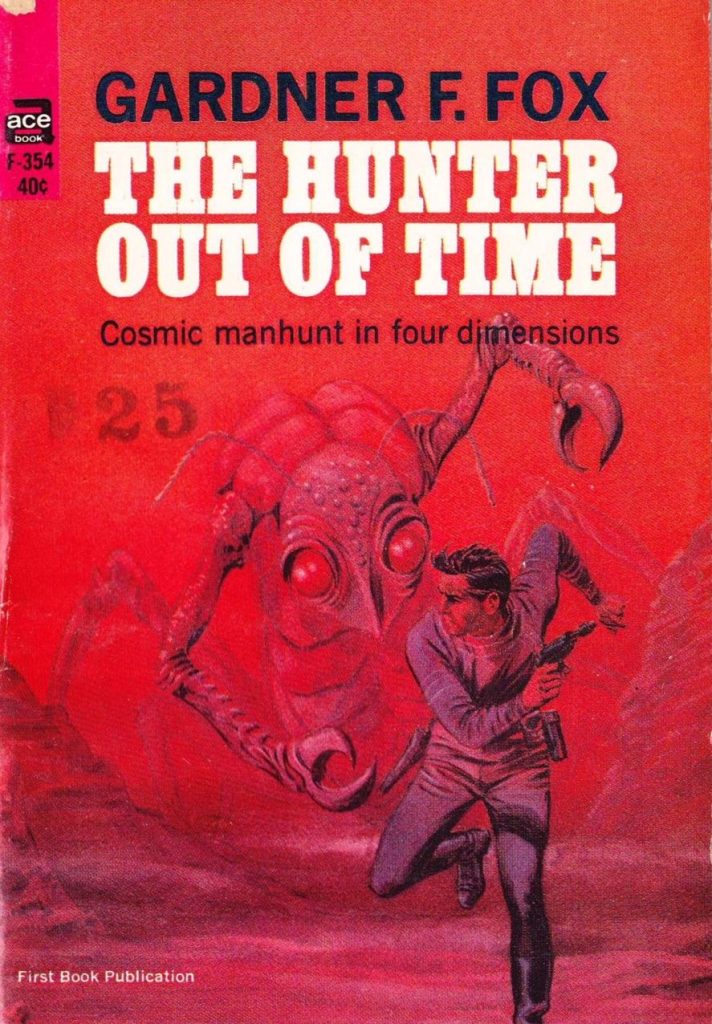

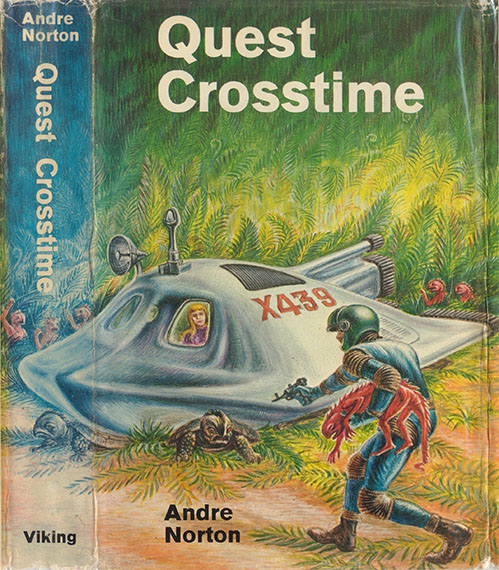

![[October 24, 1965] "What time is it?" (October Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/651024covers-1-672x372.jpg)

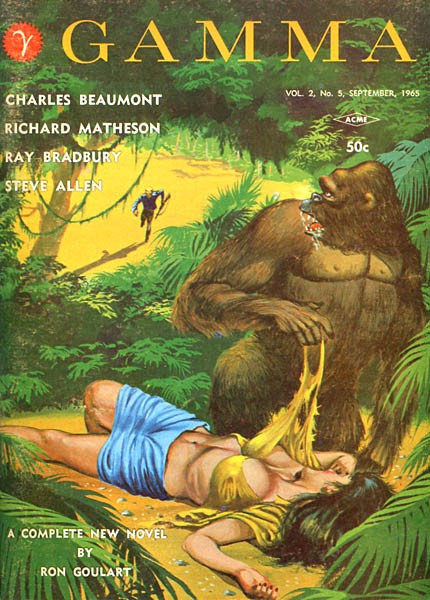

![[September 22, 1965] Foul! (September Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/650922covers-656x372.jpg)

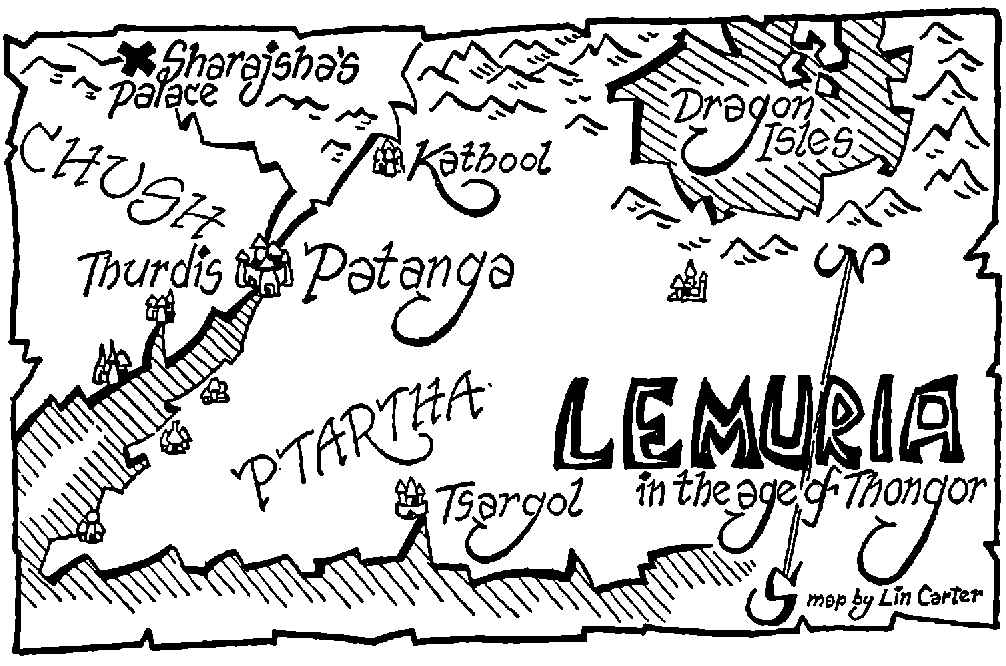

![[September 10, 1965] So Many Thews (Lin Carter's <em>The Wizard of Lemuria</em>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Cover-Wizard-of-Lemuria-672x372.jpg)

width="150"/>

width="150"/>