It's a bad time to be an experimental animal, if there ever was (or will be) a good one.

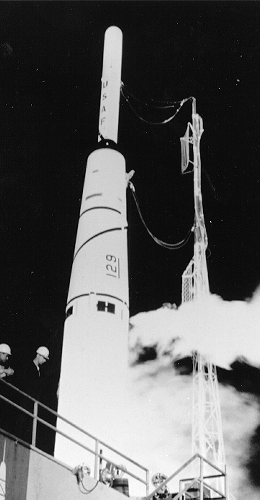

The Air Force launched Discoverer III last night with a payload of four plump black mice. As you know, if you read the papers or my column, Discoverer is a satellite program for shooting missions into polar orbit (i.e. over the poles, ultimately covering the entire Earth) ostensibly for the purpose of sending biological specimens into space and then recovering them in a detachable capsule.

Of course, a polar orbit is particularly good for reconaissance, and a detachable capsule can carry film as well as mice. I'm sure the Soviets aren't buying the "space science" angle any more than I am. Still, if we get any science out of the program, that's an added bonus.

Unfortunately, the mice of Discoverer III can't catch a break. Last week, the launch was scrubbed because telemetry from the mice had ceased. The technicians thumped on the nose cone, thinking the mice were asleep. They were, in fact, dead, having eaten the krylon coating of their cages.

A few days later, the launch was scrubbed when the nose cone sensors returned a 100% humidity level. Turns out that the mice had urinated on the sensors (a similar incident looks to have happened on one of last year's Thor-Able flights).

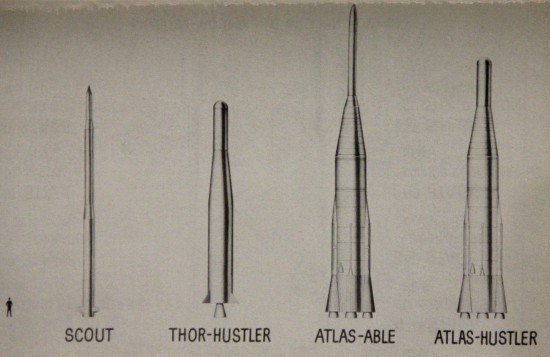

Yesterday, the rocket finally launched, but the second stage of the Thor-Hustler rocket flipped the payload and drove it straight into the Pacific ocean. Nothing could have survived that.

I understand that this incident has piqued the ire of several organizations promoting the ethical treatment of animals, particularly as this comes right on the heels of a suborbital Jupiter test flight on May 28, which had the monkeys, Able and Baker, as unwitting passengers. Though the mission was a success, I have it on good authority that Able died the other day after an unsuccessful surgery to remove an electrode. Six months before, a similar flight resulted in the death of its passenger, Sam the monkey. I wonder if the Air Force will abandon the pretense of the bio-medical mission and just launch cameras from now on.

So that's that. I believe there's another Discoverer launch scheduled in a few weeks along with another Vanguard shot. I'll report on them if and when they happen. In the meantime, I hope you enjoyed this month's Galaxy, and I'll finish up my report on the August issue in two days!

In the meantime, let's hoist a glass to our intrepid, lost rodentnauts. You deserved better.

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has comments. Please comment here or there.