Two days ago, there were three active satellites—two Vanguards and one Explorer.

Yesterday, there were two: Vanguard 3 has gasped its last beep.

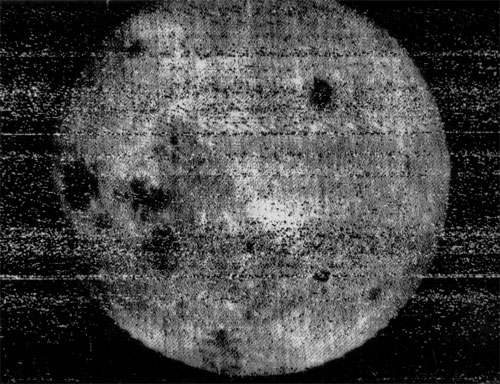

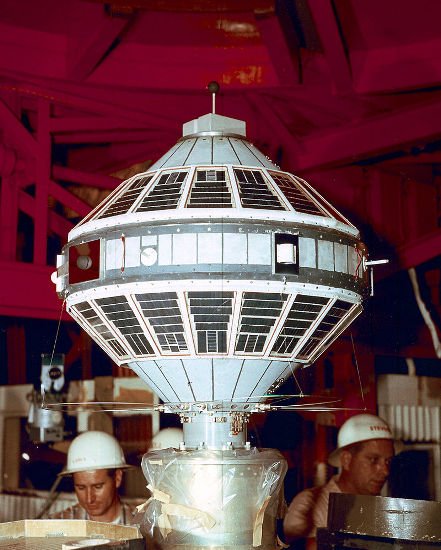

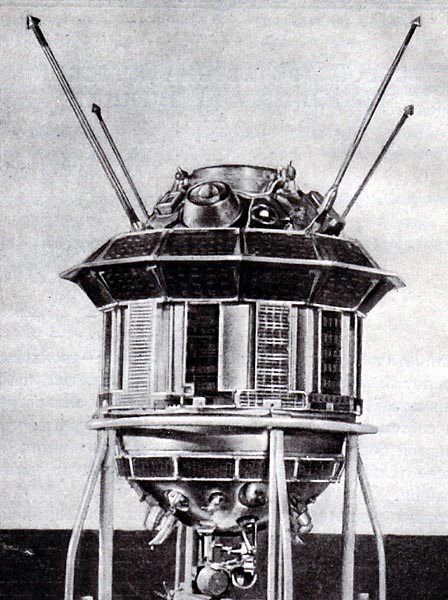

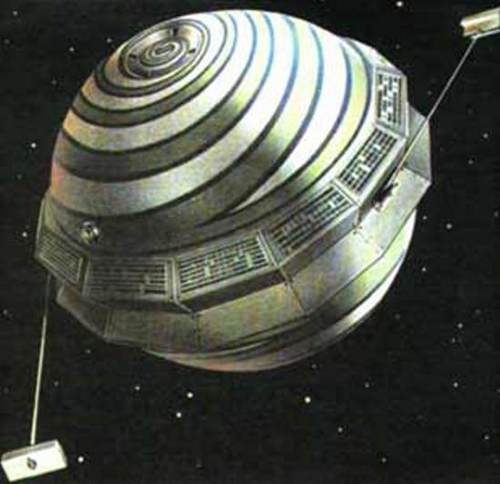

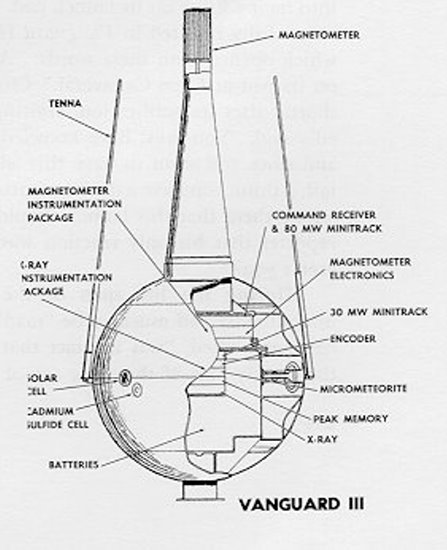

For 84 days, the last of the Vanguards circled the Earth, returning data from its solar X-Ray detectors, its magnetometer, and its micrometeoroid sensors from an orbit higher than that of its dumber, smaller older brother, Vanguard 1.

Did you know that the Sun emits X-Rays? That's what happens when you heat gasses to millions of degrees Kelvin; such temperatures are common in the solar corona, the bright fringe of gas surrounding the sun's disk that one can see during a solar eclipse. The atmosphere absorbs most extraterrestrial X-Rays, so a satellite is needed to gather comprehensive data. Sadly, all of the energetic particles trapped in the Earth's Van Allen Belts swamped Vanguard 3's detectors, and no useful data were obtained.

On the other hand, Vanguard 3's magnetometer did a heck of a job, returning more than 4000 signals, nearly 3000 of which were of high quality. We have never had such a comprehensive map of our planet's magnetic fields, and it is likely that scientists will be studying these results for years to come, learning how these fields interact with the solar wind to cause phenomena from radio storms to aurorae.

Speaking of radio, if you've ever listened to your shortwave, you might have heard "Whistlers"–those enigmatic sound that calls to mind a skyrocket flying overhead or birds chirping or even a flying saucer. Such signals have been heard since radios were invented, and it is now known that they are emitted by lightning and propagated in the ionosphere. Vanguard 3 was able to "tune in" to Whistler emissions with its magnetometer, which allowed scientists to make some estimates of the density of electrons in the ionosphere. Two for one is a good deal!

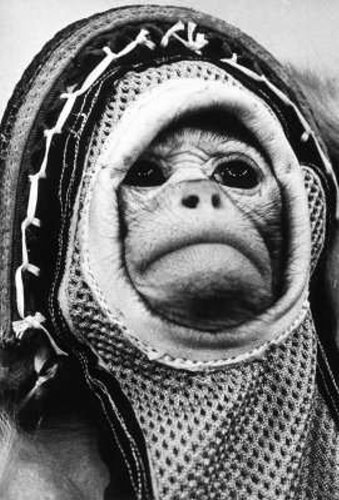

No micrometeoroids pierced Vanguard 3's hull for the duration of its mission, but that doesn't mean the satellite didn't run into its share of space junk. The first preliminary estimates from returned data suggest that 10,000 tons of space dust crash into the Earth's atmosphere every day. That sounds like a lot, but considering that it is spread out over the entire surface area of the planet, it's a negligible concern to a small satellite.

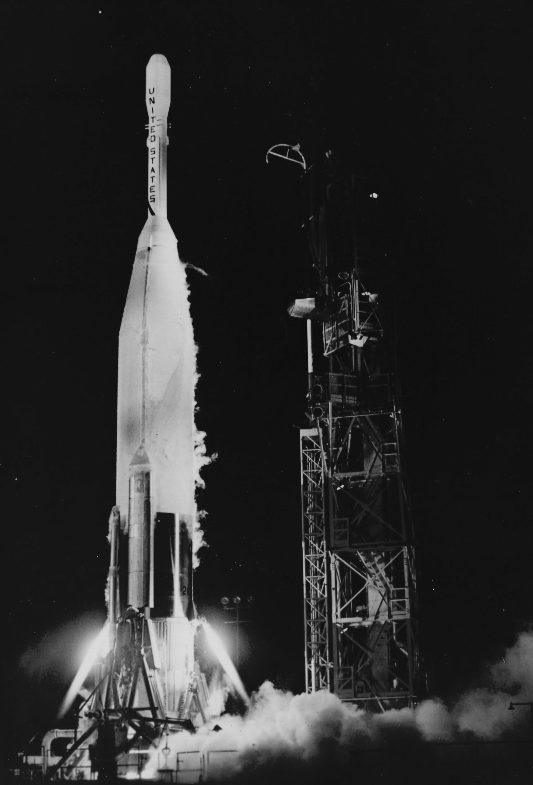

With the silence of Vanguard 3, the Vanguard program has come to a virtual end (though Vanguard 1 still keeps beeping away). Three successful launches out of eleven seems like a pretty lousy record. Consider this legacy, however: the bonanza of returned data, the comparative inexpensiveness of the program, the first stage being turned into the Vega second stage booster for other rockets, the second and third stages being used on the Atlas Able and the Thor Able rockets, the Vanguard worldwide signal receiving station pioneering space communications. Vanguard surely must count as a raging success. Moreover, Vanguard set an important precedent by showing that rockets can be used for purely civilian purposes as well as for sending weapons of mass destruction across the globe.

If my epitaph is half as laudatory, I shall be a very happy corpse.

Up next—The Twilight Zone and then… Astounding!

Note: I love comments (you can do so anonymously), and I always try to reply.

P.S. Galactic Journey is now a proud member of a constellation of interesting columns. While you're waiting for me to publish my next article, why not give one of them a read!

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has comments. Please comment here or there.