I promised an exciting week in space flight, and I'm here to deliver. Both the Air Force and NASA are all smiles this week thanks to two completely successful missions that mean a great deal for our future above the Earth.

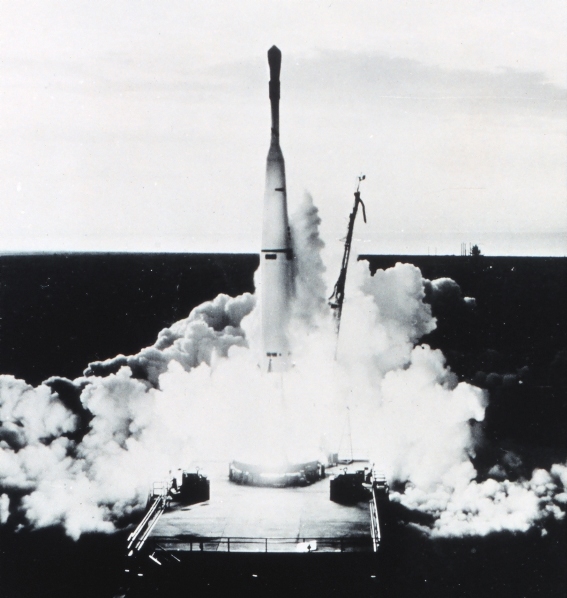

First off, the military side. 13 had proven to be a lucky number for the Air Force with Discoverer 13 performing perfectly: from launch, to orbit, to capsule re-entry, to recovery. This is a big deal–for the past year and a half, the Air Force has been struggling with its dud of a program.

Ostensibly, the aim of Discoverer is to test a biological capsule return system as a prelude to manned space travel. I suppose this is more plausible now that the "Dynasoar" spaceplane, a successor to the X-15 rocketplane, is in the first stages of development.

On the other hand, none of the Discoverer capsules since the early ones have carried live animals, and I find it hard to believe the Air Force would try thirteen times to test a capsule return system that has no direct connection with any upcoming Air Force project.

What is more likely is that the biological mission is a cover, or at the very least, incidental, just like when mice were launched on nosecone test shots of the Thor missile. So what do you do with a recoverable capsule that circles the Earth in a polar orbit, overflying every inch of the Earth as it goes? The same thing you can do with a U2 spyplane, but with no worry about being shot down–at least for now. Given the strain that the incident back in May had on international relations (and you've probably all read yesterday's headline about downed pilot Gary Powers' "confession"), I think this is a positive development.

On to the civilian side. Let's talk telephones: currently, to make a telephone call to another continent, one has to use undersea cables. Not only does this pose a bottleneck to transmission, but one can only place a call to a place cable has been extended.

In the United States, Ma Bell got around the phone line bottleneck by using microwave transmitters to relay calls. That's why you've seen phone towers popping up all over the country, and nearly a quarter of all calls now go through this system. But microwaves work in a straight line… and the Earth is round. To send a microwave message around the planet, one needs a signal tower hundreds of miles tall!

12 years ago, science fact and fiction author, Arthur C. Clarke, wrote about such a tower: the orbital communications satellite. This morning, NASA brought us one step closer to building this virtual tower.

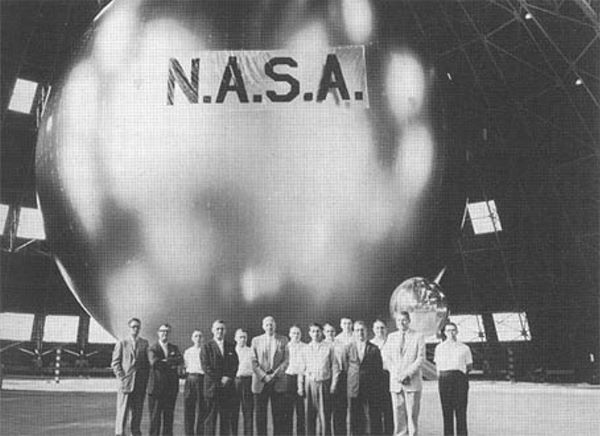

On the face of it, Echo 1, launched this morning on the new Thor Delta booster, is not that impressive. It's actually just a giant balloon with a couple of radio beacons on it. But it's a balloon you can bounce messages off of… to anywhere. It's the first generation of a class of satellites that one day will allow you to pick up the phone and make a call to anywhere in the world. Or allow you to receive television channels from across the globe.

Echo will also be a scientific satellite. NASA has tried several times to launch a big balloon into orbit to measure atmospheric density at high altitudes. Now we've got one. As a bonus, it makes a pretty, easily seen addition to the evening sky.

Thus concludes the latest Space News wrap-up, one that makes up for July's dry spell. I'll be back in a couple of days with an update from the world of science fiction.

Stay tuned!