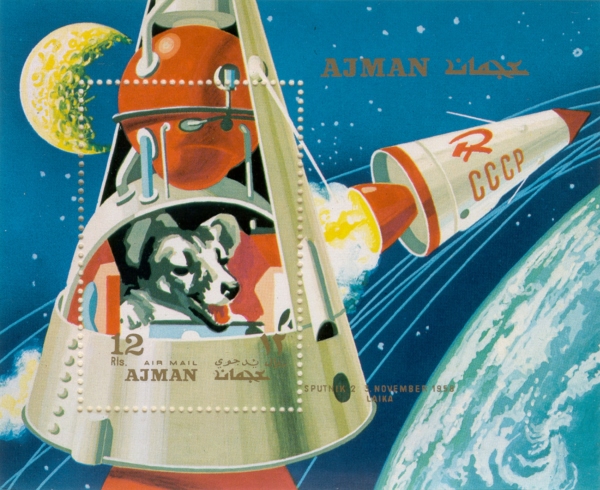

The American manned space program is on a tight schedule if it wants to place an astronaut in orbit before the Soviets. The Communists already have a striking lead. They had it three years ago when they launched the first Sputnik, and they've maintained it with the recent Sputnik 5, which featured two Muttniks, who were returned safely to Earth after an orbital flight.

It may well be that, as I write this, the Soviets will already have put a man in space.

NASA is moving at as brisk a pace as they can manage while doing their best to guarantee the safety of our spacemen. I can only imagine the frustration and impatience of the seven Mercury Astronauts, who were picked a year and a half ago as they cool their heels watching the test program play out.

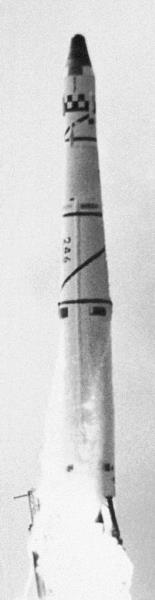

So far, we've seen several low altitude launches of the Mercury spacecraft (Little Joe). There has been a test of the Atlas orbital booster (Big Joe). But there had yet to be an all-up suborbital test of the Mercury-Redstone, mimicing the first few missions that will be flown.

Until the day-before-yesterday.

MR-1 has been on the launchpad at Cape Canaveral in Florida since late October. No pilot was assigned to the Mercury capsule, not even a monkey or a dog. The flight was just to ensure that all of the components would work properly during a 15-minute trip. The mission was originally scheduled for November 7, but a sudden loss in fuel pressure during the countdown caused launch to be aborted.

A similar problem was caught and fixed on the launch pad the morning of November 21. As the count went to zero, all systems were go. The Redstone booster ignited at 9 a.m.

And promptly shut off a second-and-a-half later. The booster stack was just four inches off the ground, and it settled back onto its fins without tipping over. But the true ignominy of the event happened at the top rather than the bottom of the stack. The escape tower, designed to drag the Mercury capsule to safety in the event of a booster failure, took off like a scared rabbit but left the spacecraft behind. Adding insult to injury, the main and reserve Mercury parachutes then popped out the top of the capsule. You probably saw this comic event on the TV news.

Yesterday, some brave engineers went out to unplug the booster and figure out what went wrong. It turns out that the culprit was a safety mechanism, a little two-prong plug designed to shut off the booster engine if there was too much of a time delay between the disconnection of the prongs as the rocket launched. The plug has been designed for the stock Redstone missile; the Mercury-Redstone combination, being heavier, took longer to launch and thus set off the safety mechanism.

The booster is damaged but reusable. We'll likely see it fly in December. Still, it's a setback in the program, which still has a few more test flights to go until a person can be launched. I'm guessing we won't see an American in space until next Spring or Summer.

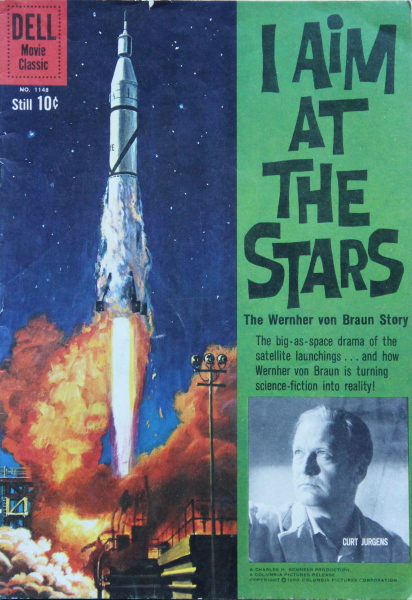

![[Nov. 21, 1960] <i>I aim at the Stars</i> (but sometimes I hit London)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/601121stars-412x372.jpg)