By Ashley R. Pollard

Looking back to October the 4th 1957 when Sputnik was launched, it’s hard to believe that only five years have passed since that fateful day when Russia beat Britain and America into space (perhaps my American readers will say that Britain had no realistic chance of getting into space first, which I would agree with, but for the Western nations to be beaten by the Russians – now that’s the thing.)

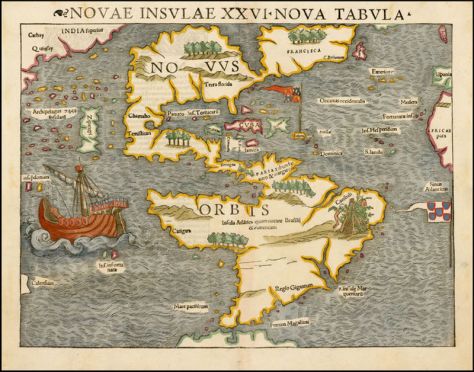

With Sputnik, humanity transitioned from flying through the air to moving through the vacuum of space, where no living animal can survive without a pressure suit. The only other time that I can think of when a paradigm shift of this nature took place would be back when the first hot-air balloons were invented. This provoked the discussion, at the time, that this was the invention of travelling through the air.

As I read the history of hot-air balloons, the idea of travelling through air as an invention seems odd to me. But as language evolves over time, so do concepts like invention, which has moved from the original Latin meaning of discovery to the more modern meaning of a process or device. Though by modern I should clarify that I mean "from the fifteenth century," which is not surprising given the changes that arose from the Renaissance, and everything that came out of rediscovery of the knowledge of the ancient Greeks.

For those who look back on the past with rose-tinted glasses I will remind my readers that the times I’m writing about were surrounded by their own troubles. The Turkish conquest of Constantinople in 1453, for example, which led to a westward exodus of Greek scholars that fuelled the rediscovery of ancient thinking. One can argue that today’s troubles, with West and East facing off against each other, is just part of the story of humanity's struggle between its biological drives versus its intellectual aspirations.

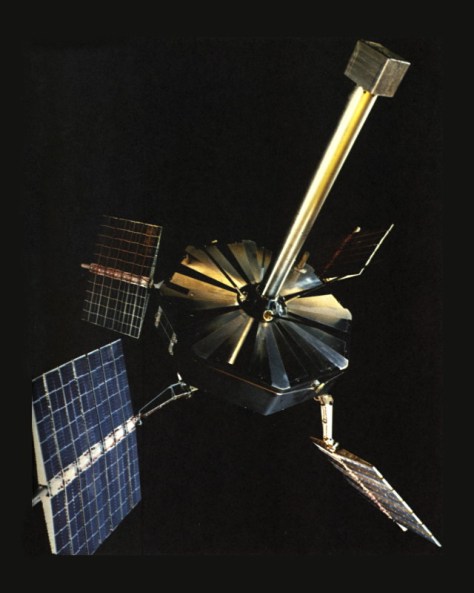

Almost equidistant (physically, though not ideologically) from the Free and Communist worlds, Britain is about to become Earth's third nation to practice the "invention" of travelling through space. Admittedly this puts us behind America and Russia, but as the Yanks are wont to say, this still makes us a contender. We are calling our satellite Ariel One, more prosaically referred to as UK-1 or S-55. This program grew out of proposal by the British National Committee on Space Research to NASA that came from a discussion at a meeting of the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) to study the Earth’s ionosphere.

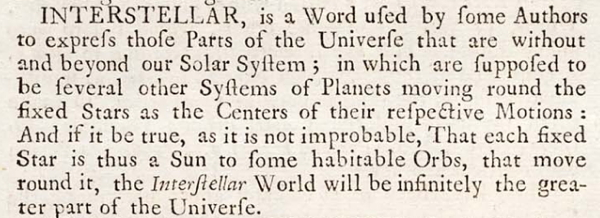

What is the ionosphere? It is that layer high up in the Earth's atmosphere where the sun's energy strips the thin air of its electrons, creating a charged barrier to radio waves. It is this layer that allows British and American "Hams" to talk to each other across thousands of miles of ocean. Understanding how the ionosphere works not only has practical implications for engineers, but is also vital to modelling the atmosphere as a whole. The rewards to science will be tremendous.

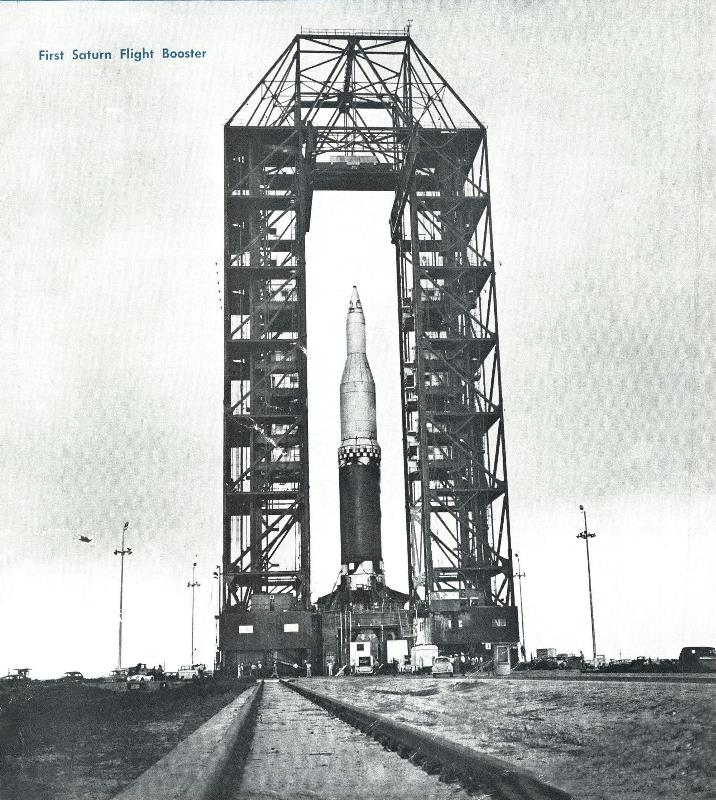

I must confess that while Ariel One may be a British satellite, it was made in America for us by the NASA Goddard Flight Center. Our satellite will launched atop a Thor-Delta rocket aka Delta DM-19, which is a variant of the Thor-Able booster that launched some of America's first satellites, and is due to be launched on the 26th of April from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Launch Complex 17A.

The Thor rockets were designed for the United States Air Force as intermediate range ballistic missiles (IRBM), which became redundant for purpose after the introduction of the Atlas intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). So arguably this is a case of swords being turned into plowshares for science. The Thor-Delta uses a Delta rocket as its upper stage, which has the new AJ10-118 engine, and the upper stage also has cold gas attitude control jets. This allows rockets to be stabilized, and the motors can also be stopped and restarted for more precise orbital insertions than were previously possible.

The Ariel One satellite has six experiments onboard, five of which will examine the relationship between two types of solar radiation and changes in the Earth's ionosphere, and the other cosmic rays. University College London has two ionospheric experiments aboard Ariel; a Langmuir probe for measuring of electron temperature and density; and a spherical probe for measurement of ion mass composition and temperature. The University of Birmingham has a plasma dielectric constant measurement of ionospheric electron density device, which uses a different method to measure electron density that complements the Langmuir probe.

In addition, University College London has two solar radiation experiments; one will measure Lyman-Alpha ultra-violet emissions; the other will measure X-Ray emissions from the Sun in the 3 to 12A band. The sixth experiment, provided Imperial College London, is a Cerenkov detector, which will measure primary cosmic ray energy spectrum, and the impact of interplanetary magnetic field modulation on this spectrum.

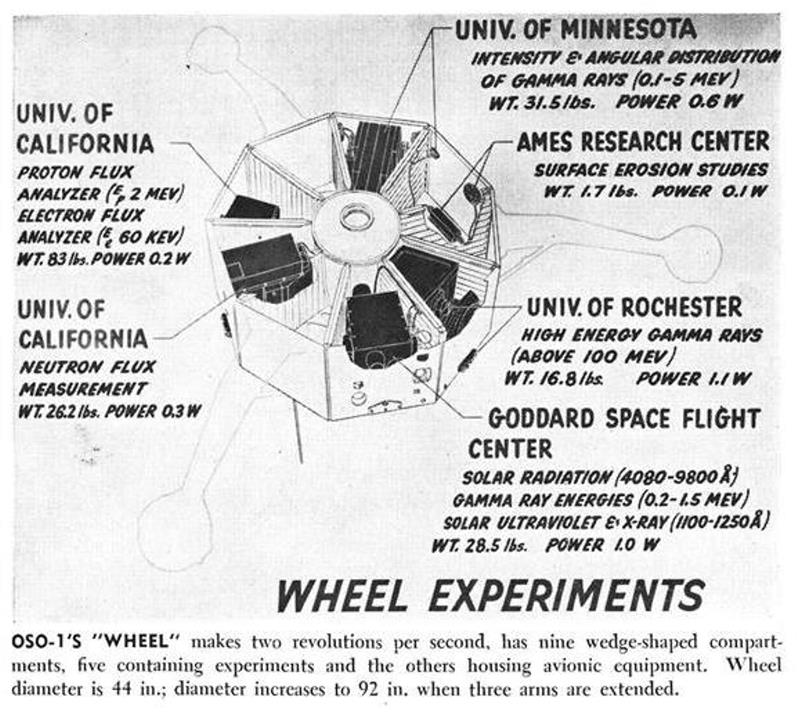

You may be thinking, "These experiments sound familiar. I know that NASA's Orbiting Solar Observatory, for example has similar detectors. Why do we need another satellite that does the same thing?"

That's an excellent question. There are three answers:

1) Just as more eyewitnesses create a stronger legal case or journalistic report, so do multiple satellites give a broader, mutually verifiable view of the same phenomena;

2) Different laboratories create subtly different experiment types. Thus, Ariel will look at the Sun with slightly different eyes than OSO;

3) Ariel represents an important first step in British space science, one that lays the foundation for future successes.

To finish this months article I must comment on the name Ariel, which is an interesting choice. Ariel is a Hebrew word found in the Bible. I understand it means either the Lion of God or Hearth of God, depending on interpretation. It is also the name of one of the moons of Uranus (recently visited by other members of the Journey).

But, one can’t help but think of Milton’s Paradise Lost or Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and my guess would be that it’s an allusion to the latter because Ariel was the servant of Prospero – and I have the highest hopes that Ariel One shall be successful in serving British science equally well.