by Rosemary Benton

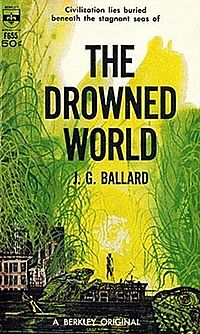

At last, the levity that I so desperately needed has been provided. Prior to reading The Drowned World I was only aware of J. G. Ballard as a name. He was well published, I knew, but ultimately a background figure to my science fiction library. That all changed on June 30th, however, when I went to the town bookstore and purchased The Drowned World. The bookseller said that it would take me no time at all to read. I found this to be true, although the time it took me to process the book was far longer than than I had expected.

J. G. Ballard's The Drowned World is a post-apocalyptic ballad performed by a select cast, and encased in a small slice of Ballard's much larger story of the evolution of Earth. The location of the story takes place in an entirely fictional future vision of Earth. Due to a sun which has become unstable, the Earth is rapidly heating. The remaining 5 million humans have fled to the Antarctic circle where the temperature is a tolerable 85 degrees. The Earth's equator, by comparison, is close to 200 degrees on any given day. Bombarded by solar radiation and spurred on by the intolerable heat, flora and fauna have begun to mutate to prehistoric shapes and sizes. Enormous iguanas, crocodiles and snakes are now a common site in Berlin and London, whose streets and buildings are now submerged by upwards of 50 feet of water. Large bat-sized mosquitoes bash themselves relentlessly against the wire meshes and cages encircling the last human bastions in London, while dog-sized bats feast upon the oversized insects. The evolution of disease has kept pace with the changing environment; malaria becomes the most common affliction hitting the human population.

Much of Europe has been reduced to lagoons nestled between vast expanses of jungle and silt dunes. In one such lagoon, floating over the decaying architecture of London, sits the stage and players of the story. Central to the book are the biologists Dr. Robert Kerans and Dr. Bodkin, the emotionally distant heiress Beatrice Dahl and the villainous looter, Strangman. Surrounding them are the rest of the research team sent to monitor the changing landscape, and Strangman's crew of tribalistic-minded followers.

On a small scale Ballard includes the traditional elements of science fiction and action-adventure. There is a hero, a villain, a love interest who is desired by both the villain and the hero, a climax to the tension between the battle of the hero and the goals of the villain, tied off nicely with a sacrificial confidant and companion to the hero. On a much larger scale The Drowned World offers a character study of a villain and a hero, both of whom are morally ambiguous, as they navigate a truly alien environment with totally different sets of rules for survival.

To best dissect The Drowned World I think it is necessary to take a look at the three major players to Ballard's drama: Ms. Dahl, Strangman and finally Dr. Kerans. Ms. Dahl is perhaps one of the more developed characters of the story, and yet her journey is largely symbolic. A key element of Ballard's world is that not only is the physical world around humanity devolving, but so is the unconscious mind of humanity. Plagued by memories of survival urges now unlocked after centuries of culture and socialization, humans by and large are subjected to nighttime visions of hot, fiery landscapes and looming reptilian danger. Ms. Dahl is one of the first characters who we see suffering from these apparitions.

We read about her trying to deal with them through alcohol and cool detachment. Her acceptance of the end of the human world is made all the more evident by her refusal early on in the book to leave the lagoon for the more tolerable temperature of the northern settlements. Despite the coming rains, the rise of the water, and the abandonment of the post by the well equipped scientific team, she shows little interest in leaving behind her home. Yet in the shifting pools of green, warm water with its surface disturbed by the movement of reptiles swimming in and out of the lower levels of the ruined buildings, she has managed to find an equilibrium in which she can live out her days, even as the prophetic nightmares of flooding rain and dense jungle encroachment press ever closer. She has given up fighting against nature and the universe's larger plans for the planet, and instead finds her small pleasures in dining on the dwindling reserves of fine food, sunbathing, and keeping up a cultured outward physique.

Ms. Dahl's personal journey is taking her along the same path as Dr. Kerans'. She is dreaming of an ancestral life and living it as best she can in the present. When confronted with a challenge to this backwards slide she recoils and withdraws within herself. She longs for the return to the encroachment of the water and reviles in the exposure of the land. She is unable to deal with change that could draw her on a different path from the envelopment of Earth by the sea, and ultimately it destroys her relationship with her companions Dr. Kerans and Dr. Bodkin.

Enter Strangman on his ridiculous riverboat piled high with looted objet d'art, liquor and jewelry. Like Ms. Dahl, Strangman enters the story as someone who has given in to the changing world, although he has done so in a drastically different fashion. In keeping with salvage laws and the overall objective of land reclamation, Strangman drains the lagoon in order to gain favor with the loosely upheld government. At the same time he is able to continue with his passion of surrounding himself with items of beauty from the old world. Unlike our protagonists, Strangman is not regressing backwards to a state of piteous apathy, nor is he embracing the larger time scale that Ms. Dahl and Dr. Kerans have via their million year old primitive dreams. Even though he is aware of them via conversation with Dr. Kerans, and presumably experiences them himself, he is written as an opportunist. He takes risks in sending his crew, which he provides for and never once abuses, down into the sunken city. He takes chances by draining the lagoon in order to reclaim the land and thereby more easily take its sunken riches. He is progress in a backwards way because ultimately nothing he does will have any lasting impact, but he at least fights against the insignificance of his actions and his existence.

Along this line he is also upholding the pre-drowned world, and while he revels in the finer luxuries it provided, he doesn't do so in the same way as Dr. Kerans or Ms. Dahl. While they are content with living out the lifespan of their delicious foods and luxury accommodations before the sea reclaims them, Strangman wants to make them last as long as possible. Even unnaturally so. He rejects the inevitable in favor of the possible when he drains the lagoon and likely plans to drain others in the area. He is even commended for his actions by Dr. Kerans' team when they return to the area at the end of the book and see what he has accomplished.

At last we must examine Dr. Kerans. This man, who we meet standing on his balcony of the Ritz complete with air conditioning, fine clothes and even finer furnishings, is not shaken by the thought of nearly anything involving his future. Absorbed in the visceral feel of his present environment, Dr. Kerans is a man who lives entirely in the now with little thought to the future or concern for the past. Only later does he even begin to experience the dreams that have led most of the cast to a delayed madness. At the end of the book he even embraces a futile journey south and consequently a slow, painful suicide. Put concisely he is against everything that we, as modern humans and Americans, are taught to embrace as progress – the continuous struggle against nature, the need to suffer for progress, and the need to forge your own fate. In any other story he would be the villain trying to prevent the human race from fighting back against its aggressor. Interestingly, in this story he is the hero. But why is he the hero? Ultimately I believe this can be answered by Ballard's writing style.

J. G. Ballard's writing is like a good red wine. It has body, heft, and layered flavors that reveal themselves based on how you indulge in them. I read The Drowned World over the course of several days, taking my time to sink into the atmospheric environment that Ballard creates. In short sips the book takes the reader a long way. So many descriptive analogies, metaphors and adjectives are crammed into each page that one would think Ballard had gone overboard. Yet despite his verbose world building, nothing felt repetitive and frankly, I couldn't get enough.

I lived for days on how Ballard would express his characters' wonder at the world surrounding them, and how each as an individual would contribute to the progress of the story. It is this individual experience that I believe made Dr. Kerans the hero, Strangman the villain, and Ms. Dahl the figurative totem. When one reads Ballard's dialogue it is abundantly secondary to the individual brazen actions taken by each character. This isolation, when a character acts of their own volition outside of what their companions would want or desire, is what Ballard revels in. The individual, whether walking forward or backwards in human evolution, is a lynchpin. What they see, how the environment congeals around them, and how their actions later influence others is paramount to Ballard's The Drowned World.

Thus, Dr. Kerans was the hero because he was willing to press forward into that isolation of standing behind his scientific team, and in the end, the isolation of the journey south toward the epicenter of the heat. Strangman, on the other hand, was nothing without his crew, his treasures or his need to change the world for the benefit of the many. As such he was the villain. It is an interesting reversal, and one which I believe took a cunning mind to pen. I look forward to exploring more of Ballard's works and retroactively swimming through his vast sea of published works. This book deserves a well-earned five out of five stars.

—

(P.S. Don't miss the second Galactic Journey Tele-Conference, July 29th at 11 a.m.! If you can't make it to Worldcon/Chicon III, this is YOUR chance to Vote for the 1962 Hugos!)