by Gideon Marcus

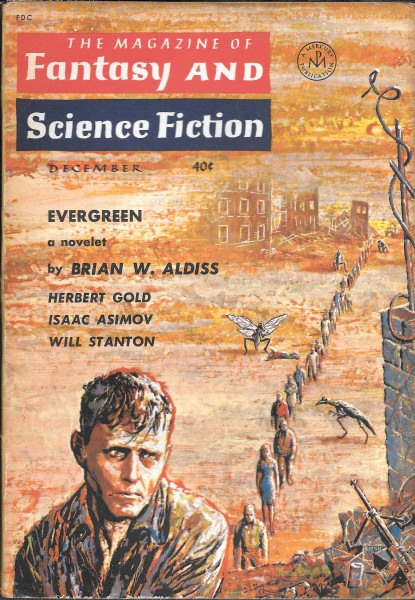

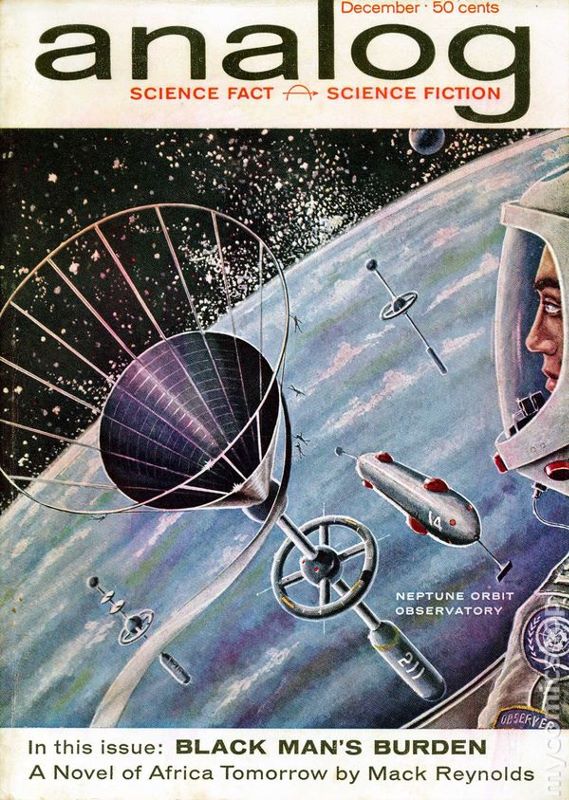

There is an interesting rhythm to my science fiction reading schedule. Every other month, I get to look forward to a bumper crop of magazines: Fantasy and Science Fiction, Analog, and the King-Sized Galaxy. Every other month, I get F&SF, Analog, and IF (owned by the same fellow who owns Galaxy).

IF is definitely the lesser mag. Not only is it shorter, but it clearly gets second choice of submissions to it and its sister, Galaxy. The stories tend to be by newer authors, or the lesser works of established ones. This makes sense — Galaxy offers the standard rate of three cents an article while IF's pay is a bare one cent per word.

That isn't to say IF isn't worth reading. Pohl's a good editor, and he manages to make decent (if not extraordinary) issues every month. The latest one, the January 1962 IF, is a good example.

For instance, the lead novelette is another cute installment in Keith Laumer's "Retief" series, The Yillian Way. I've tended not to enjoy the stories of Retief, a member of the Terran Interstellar Diplomatic Corps. Laumer writes him a bit too omnipotent, and omnipotent heroes are boring, as they have no obstacles to overcome. The challenges presented in Way, however, both by the baffling alien Yills and Retief's own consular mission, are all too plausible…and charmingly met. I am also pleased to find that Retief is Black (or, perhaps, Indian). Four stars.

There's not much to James Schmitz's An Incident on Route Twelve. In fact, if not for the engaging manner in which it's written, this rather archaic story of alien abduction would be completely skippable. As presented, it reads like a fair episode of The Twilight Zone. Three stars.

If there is a signature author for IF, it's Jim Harmon. This prolific author seems to be in every other issue of the mag (and quite a few Galaxy issues, too). Harmon is to Pohl what Randy Garrett is to John Campbell at Analog: a reliable workhorse. Thankfully for Pohl, Harmon is better than Garrett (not a high bar). The Last Place on Earth is not the best thing Harmon has ever written. In fact, the ending seems rushed, and the plot doesn't quite make sense. That said, this tale of a fellow being hounded by a malevolent alien presence, is powerfully told. Another three-star piece.

Usually, alien possession a la Heinlein's The Puppet Masters is portrayed in a negative light. But what if the society taken over is an intolerant dictatorship, and the foreign entity promotes love and brotherhood? The Talkative Tree by H.B. Fyfe won't knock your socks off, but it is a pleasant little read. Three stars.

Last of the short stories is 2BR02B (the zero pronounced "naught") by Kurt Vonnegut Jr. Like his latest in F&SF, Harrison Bergeron, it is a cautionary tale written at a grade-school level. This time, the subject is the ever-popular crisis of overpopulation. With Vonnegut, I vacillate between admiring his simplistic prose and rolling my eyes at it. Three stars.

That's the last of the short stories. Not too bad, right? A solid couple of hours of reading pleasure there. But then you run headlong into the second half of the serial, Masters of Space, and that's where the wheels come off of this issue. E.E. Evans was a prolific writer for the lesser mags between the late '40s and his death in 1958. I know of him, but I haven't read a single thing by him. There is another, more famous "E.E." That's E.E. Smith, the leading light of pulpish space opera from the 20s and 30s. He had largely stayed hidden under the radar for the past couple of decades, but he resurfaced not to long ago.

Some time between his passing and this year, "Doc" Smith got a hold of a half-finished Evans work and decided to complete it. The result is a almost skeletal, decidedly old-fashioned novel, something about humans who once straddled the stars but were coddled to senescence by the android servants they created. Millennia later, the descendants of the old Masters pushed out into the galaxy again, only to face the indescribably sinister Stretts. Masters isn't bad, exactly. It's just not very good. Smith's writing holds no appeal for me. I recognize Smith's importance to the field of science fiction, but time has not been kind to his work, nor have Doc's skills improved much over the years. I made it about 60% through this short novel, but ultimately, I simply have better things to do with my time. Two stars (and I revised my opinion of the previous installment, too).

In many ways, IF is the anti-Analog. That magazine usually has great serials and mediocre short stories. Oh well. At least they both have something to offer.

Coming soon: the next installment in an ongoing series. Don't miss this Galactic Journey exclusive!