by Gideon Marcus

Braving My Shadow

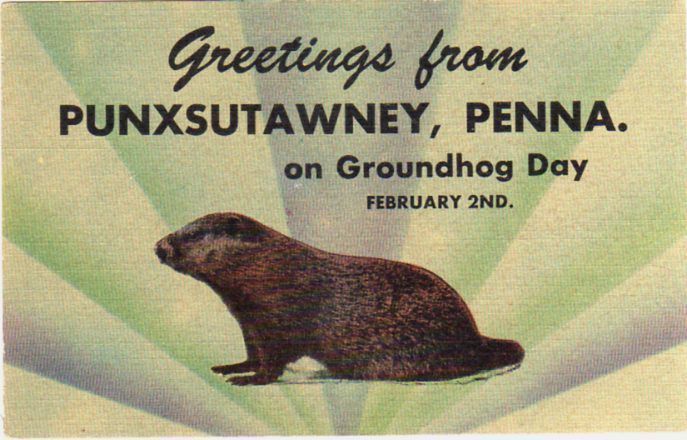

Every year on February 2, a groundhog named Punxatawney Phil decides if it's worth vacating his winter hiding place before spring.

For Galactic Gideon, on the other hand, the end of winter always happens in February. The annual convention season wraps up around Thanksgiving with the little gathering of Los Angeles Science Fiction Fans called "Loscon." There is a lull of events in December and January, but well before the vernal equinox, the Journey's dance card is full. In fact, I've already been to two events in as many weeks, and I've got another one planned next weekend!

My birthday weekend was spent at a small Los Angeles conclave called Escapade, where we discussed Johnson's tax cut, The Outer Limits vs. The Twilight Zone, and the more peculiar elements of the TV show, Burke's Law. Unusually for sf-related gatherings, most of the attendees were women.

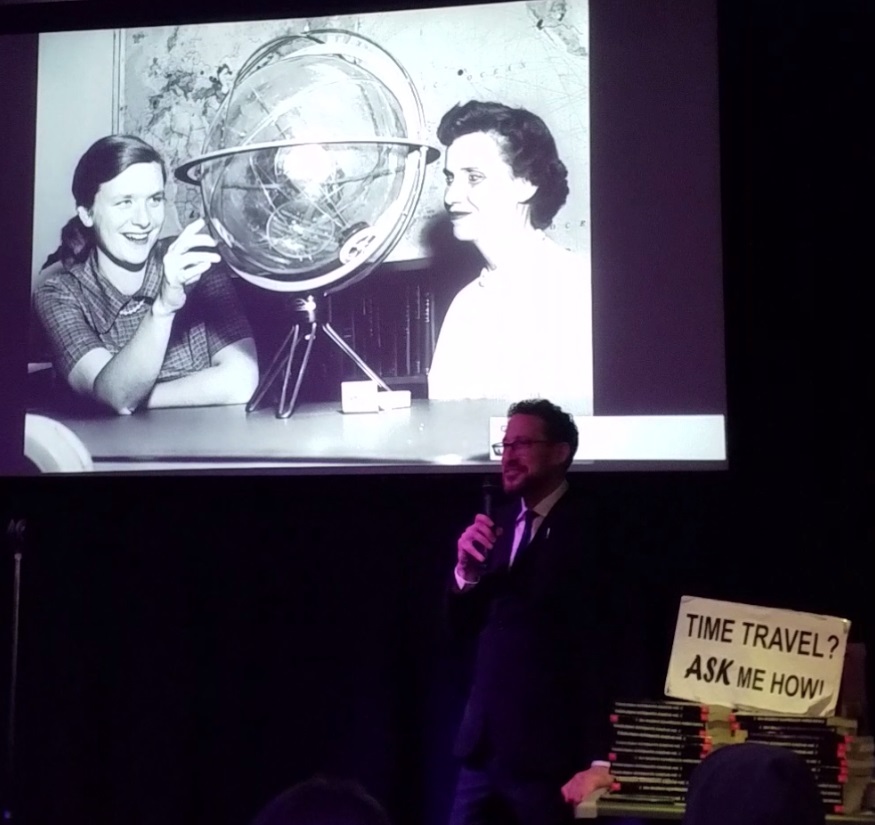

Last night, I presented at a local pub on the woman pioneers of space, the scientists, engineers, and computers I first wrote about a couple of years ago. It was a tremendous event, and I am grateful to the folks who crowded the venue to bursting.

The Issue at Hand

In contrast to these past two events, the last magazine of the month is mostly stag. Nevertheless, the March 1964 Analog is still a pretty good, if not outstanding, read:

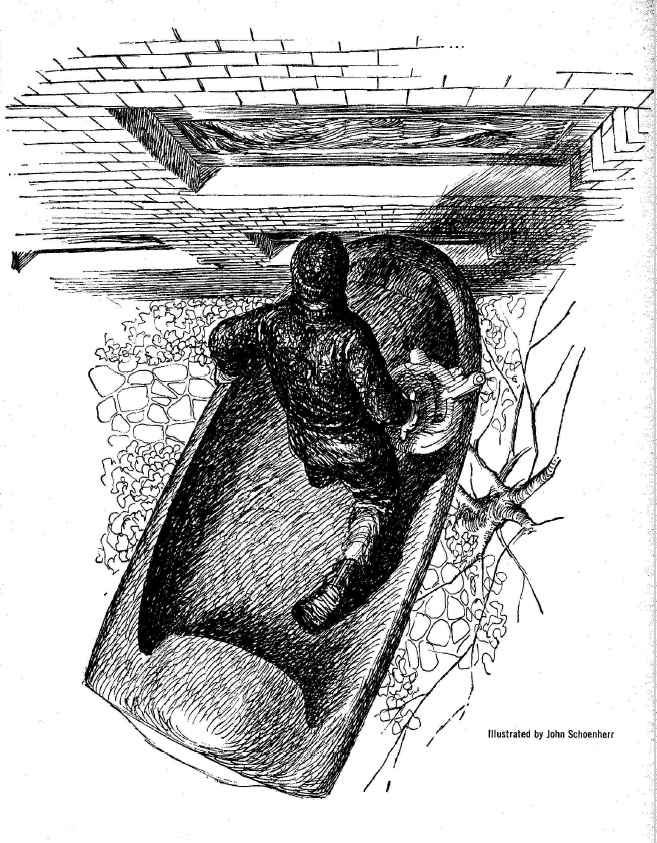

Cover by Schoenherr, illustrating Spaceman

Clouds, Bubbles and Sparks, by Edward C. Walterscheid

There are three qualities by which I rate science fact articles: Are they fun to read, do I learn something, and are there bits where I feel compelled to joggle the elbow of the person next to me (usually my wife) and relate to them a neat bit of scientific trivia.

This latest piece, on the detection of subatomic particles, excels in all three. If you ever wanted to know how a geiger counter works, or what a cloud chamber is for, or what those tubes in our scientific spacecraft do, this is the article for you.

Five stars.

Spaceman (Part 1 of 2), by Murray Leinster

The dean of Golden Age science fiction returns with yet another entry in his well-developed galactic setting. In the Leinster-verse, perhaps best represented in his Med Series stories, interstellar travel is a bit like ocean travel in the 19th Century — reliable but not instant. Colonies are days or weeks apart, and what separates a thriving hub from a backwater is the existence of a magnetic landing grid on which cargo ships can land and trade.

Spaceman is the story of Braden, a ship's mate who seeks passage aboard the Rim Star. This giant vessel is an experiment — it carries an entire, unassembled landing grid in its hold, and it also possesses the rockets to make a landing on a world without a grid. Having one ship bring an entire landing grid for installation has never been tried before, but no one is certain that the ship can fulfill this purpose. Moreover, there are all sorts of bad omens for Braden: he is waylaid by the ship's crew while on his way to his interview; the captain seems negligent to a criminal degree, and the obsequiousness of the ship's steward rings false. In spite of these alarms, Braden takes the job anyway, feeling it his duty to see the ship through its special mission, and also to protect the six passengers the Rim Star has aboard.

The other shoe drops near the end of this first part of what's promised to be a two-part serial. The crew is, in fact, up to no good, and the entire ship is imperiled. Stay tuned.

It's not a bad yarn. The plot is interesting and the characters reasonably developed. Where it creaks is the writing. Leinster has developed an odd sort of plodding and padded style of late, with endless sequences of short sentences and whole paragraphs that repeat information we already know. Used sparingly, I suppose it's a style that could be effective. Used excessively, it slows things down.

And then, there's this gem of a line (an internal musing of Braden's) on page 36:

When a man admits that a woman is a better man than he is, he may be honest, but he should be ashamed.

Three stars, barely. We'll see what happens next month.

The Pie-Duddle Puddle, by Walt and Leigh Richmond

Recently, in Papa needs shorts, the Richmonds showed us how a four-year old child can save the day even with an imperfect understanding of the situation. The husband-and-wife writing team try it again, this time from an even more exotic viewpoint (which you'll guess pretty quickly). It's not nearly as effective or plausible a piece. Two stars.

Outward Bound, by Norman Spinrad

I'm getting a little worried about new author, Norman Spinrad. He hit it out of the park with his first story, and scored a double with his second. The latest, about a decades-long relativistic chase across the galaxy in pursuit of the man who has the secret to superluminous travel, is barely a walk to first base. It's not bad; there's just no mystery to the thing. Three stars.

Third Alternative, by Robin Wilson

On the other hand, this first story by new author Robin Wilson is rather charming. It's a time travel piece featuring a fellow who goes back from 2012 to 1904 with naught but what he can cram into his bodily orifices (inorganic matter doesn't transport). You don't find out his purpose until the end, and it's an engaging, effective piece. Another three-star story, but at the high end of the range.

Summing up

Reviewing the numbers, it seems like leaving the burrow was worth it. Least mag of the bunch was Amazing at 2.3 stars and with no four star tales. Next was IF at 2.4 stars, again with no exceptional pieces. Fantastic clocked in at 2.7, but it had the excellent The Graveyard Heart by Zelazny; New Worlds, three stars, had Ballard's The Terminal Breach. At the positive end of the scale were F&SF and Analog at 3.3 stars — their non-fiction articles were the real stand-outs. Finally, Worlds of Tomorrow was mostly superior, definitely worth the 50 cent cover price.

Women had a banner month, producing 5.5 out of 39 new pieces (14.1%).

Looks like we'll have a warm spring!

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[March 3, 1964] Out and about (March 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640303cover-460x372.jpg)

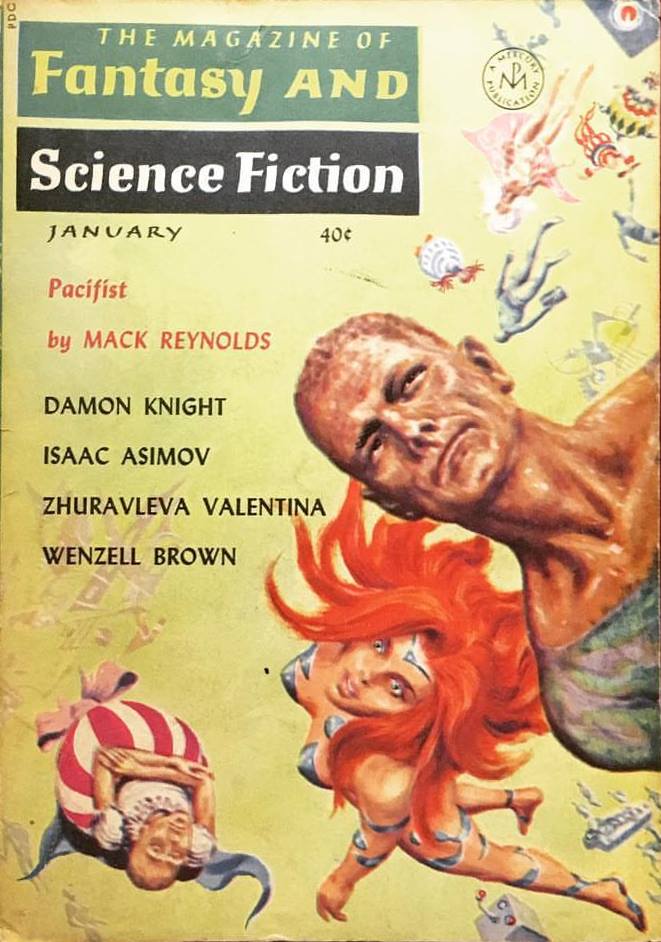

![[February 21, 1964] For the fans (March 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640219cover-665x372.jpg)

![[February 9, 1964] Bargain Basement (March 1964 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640209cover-672x372.jpg)

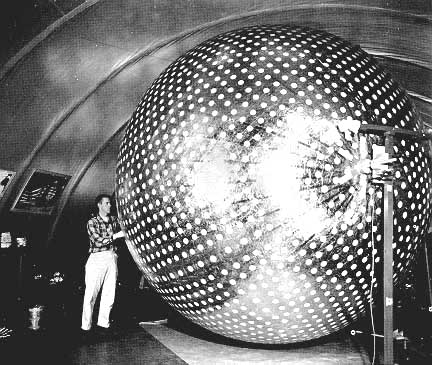

![[February 5, 1964] That was the Month that Was (January's Space Roundup)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640205echo2-672x372.jpg)

![[February 1, 1964] The Vast Wasteland (February 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640201cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 26, 1964] Sophomoric (Laurence M. Janifer's <i>The Wonder War</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640126cover-465x372.jpg)

![[January 18, 1964] Pig's Lipstick (February 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640418cover-554x372.jpg)

![[January 8, 1964] A Taste of Homely (February 1964 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640108cover-570x372.jpg)

![[January 4, 1964] Something borrowed, something blue (Ace Double F-253)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/640106f253-1-672x372.jpg)

![[December 21, 1963] Soaring and Plummeting (January 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631221cover-661x372.jpg)