by Cora Buhlert

The Best of Fantasy Past and Present

I have sung the praises of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series and the commitment of editor Lin Carter and publisher Betty Ballantine to bring the best fantasy of yesteryear back into print before. In fact, not quite two weeks ago, I reviewed Deryni Rising by Katherine Kurtz, the first new original novel to appear in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, in these very pages.

However, the bread and butter of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series is still reprinting fantasy works from the first half of the century in affordable paperback editions and making these often hard-to-find books available to modern readers.

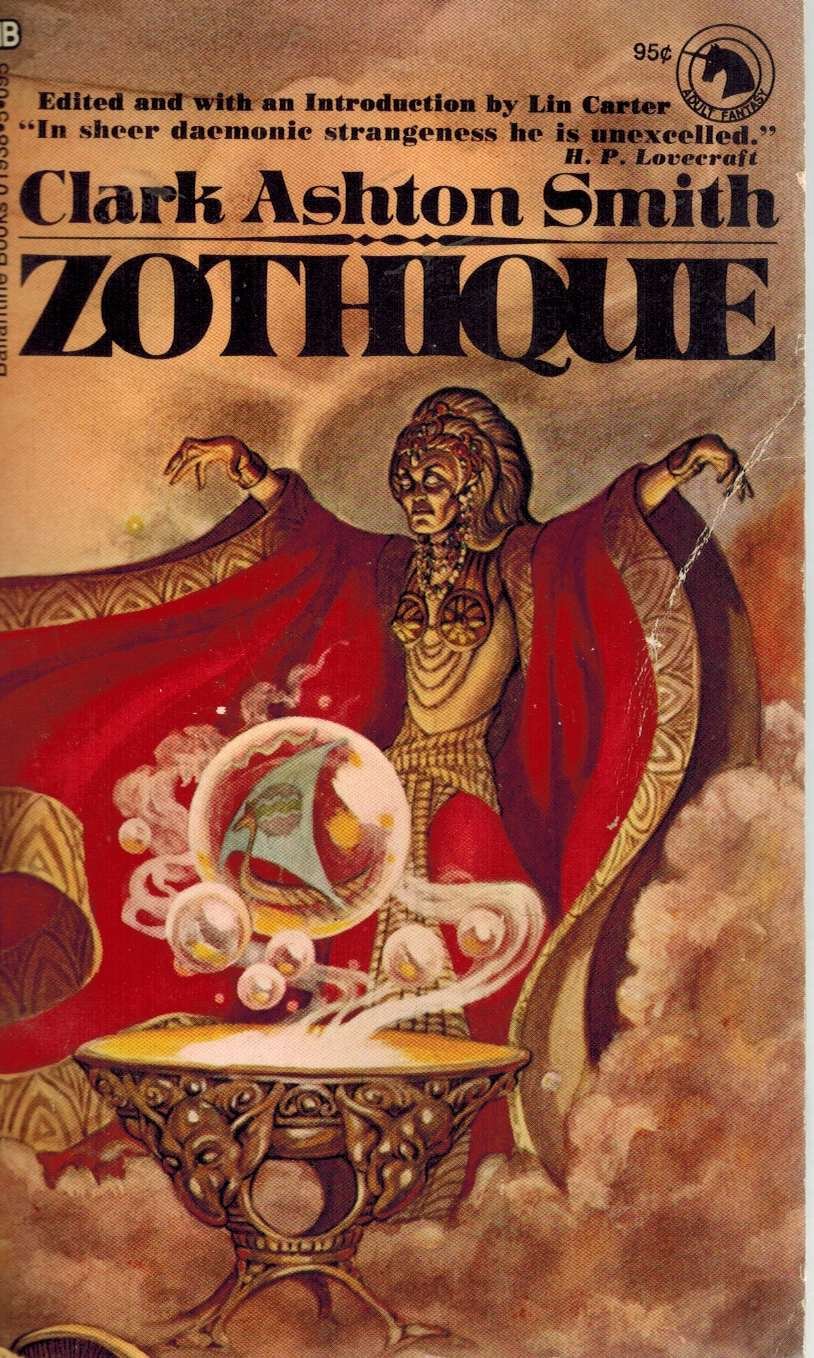

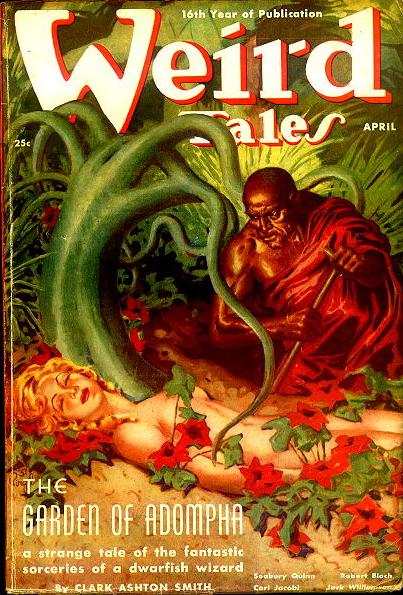

Today I want to take a look at one of these reprint volumes, Zothique by Clark Ashton Smith.

The Bard of Auburn

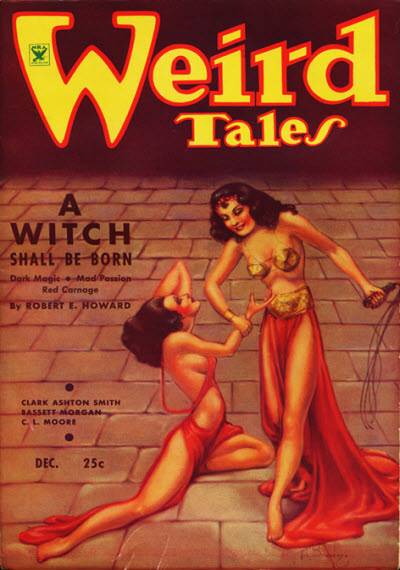

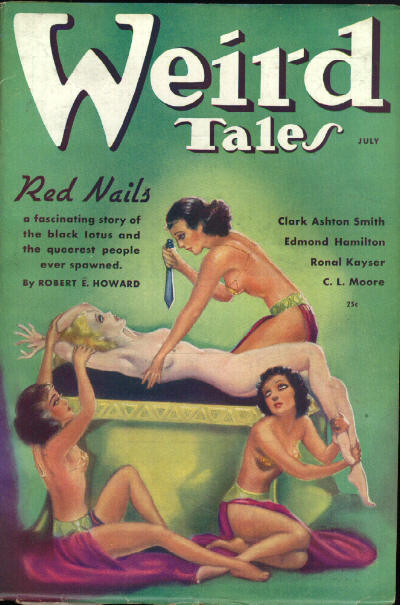

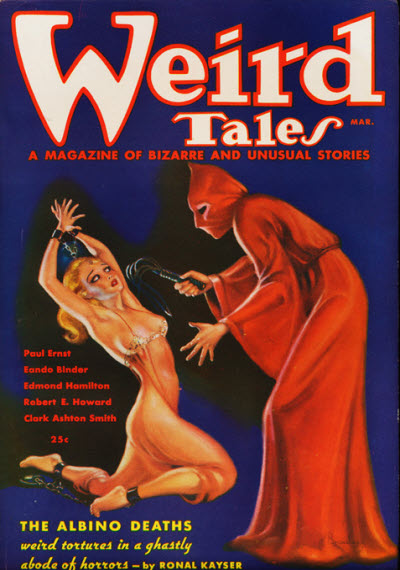

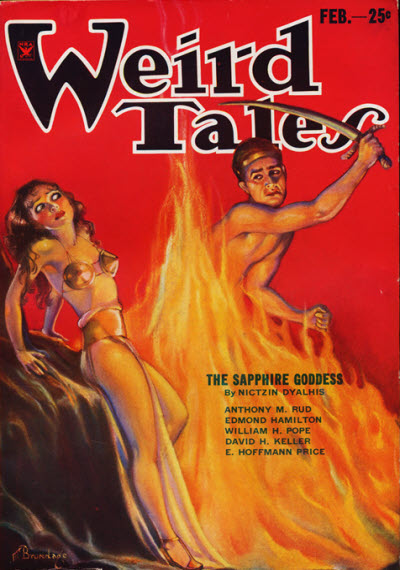

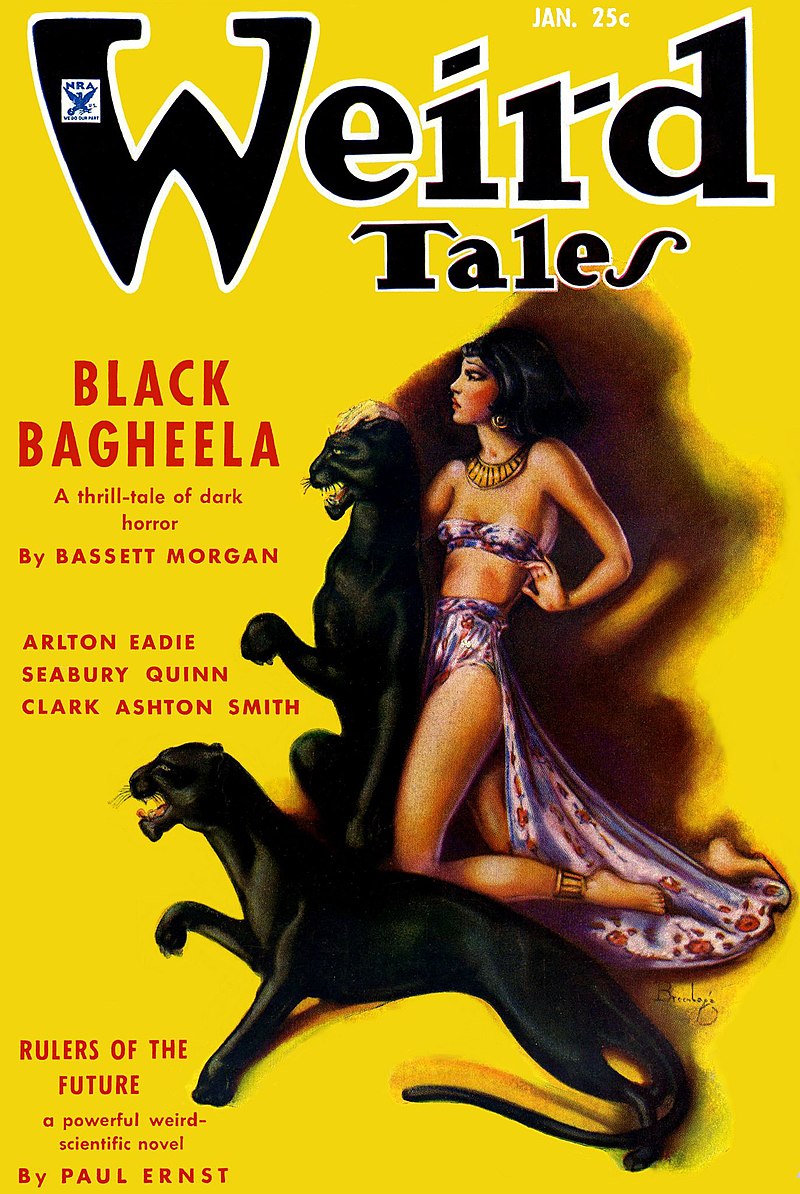

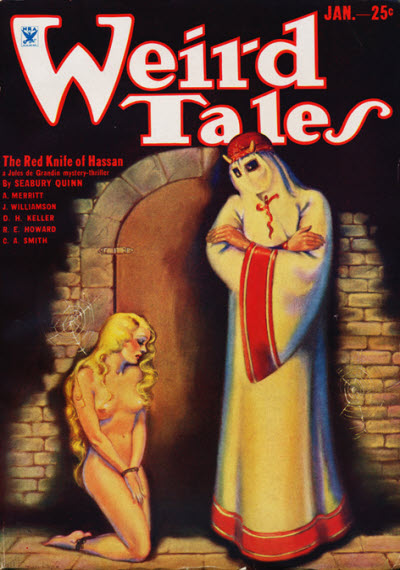

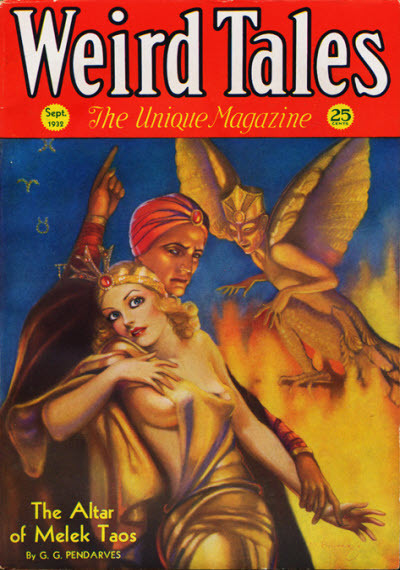

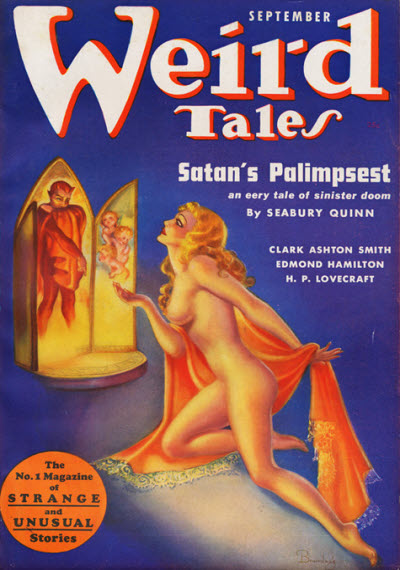

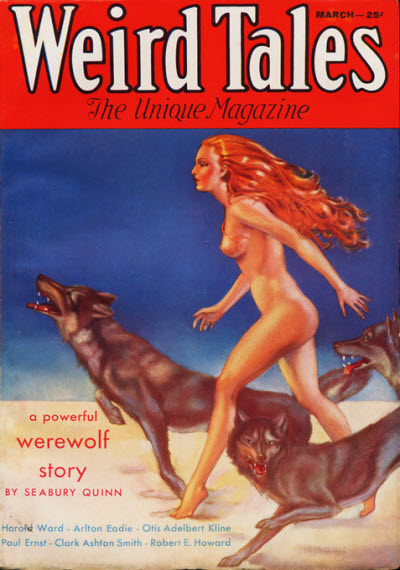

Young readers today might be forgiven for never having heard of Clark Ashton Smith. However, forty years ago, he was a mainstay of Weird Tales and one of the most unique authors to ever grace the pages of the Unique Magazine.

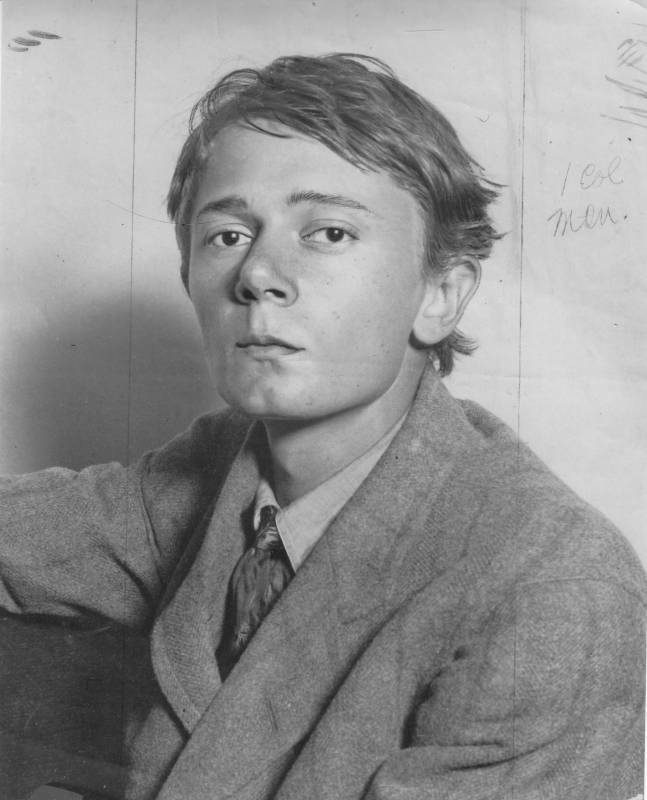

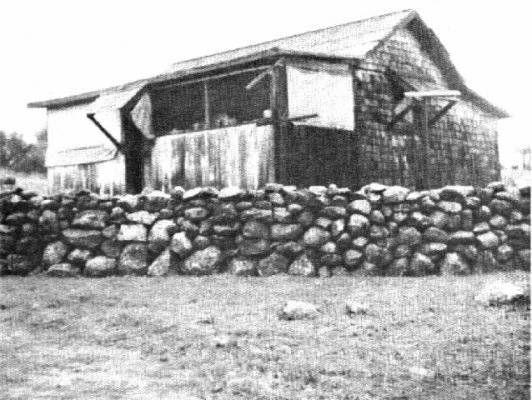

Clark Ashton Smith was born in 1893 – "three years after the death of William Morris and one year after the birth of J.R.R. Tolkien" to quote Lin Carter – and spent most of his life in a small cabin in Auburn, California. He was an avid reader, something of a recluse, and became a poet. By the early 1920s, he had several volumes of poetry published.

Smith's poetry brought him to the attention of H.P. Lovecraft, and the two men struck up a cross-continental correspondence. It was Lovecraft who encouraged Smith to submit stories to Weird Tales and other pulp magazines, when Smith's elderly parents fell ill and he found himself in financial trouble. After a few rejections, Lovecraft's advice paid off, and from 1929 onward, stories by Clark Ashton Smith frequently appeared in Weird Tales, but also in Wonder Stories, Strange Tales, Stirring Science Stories and even Astounding.

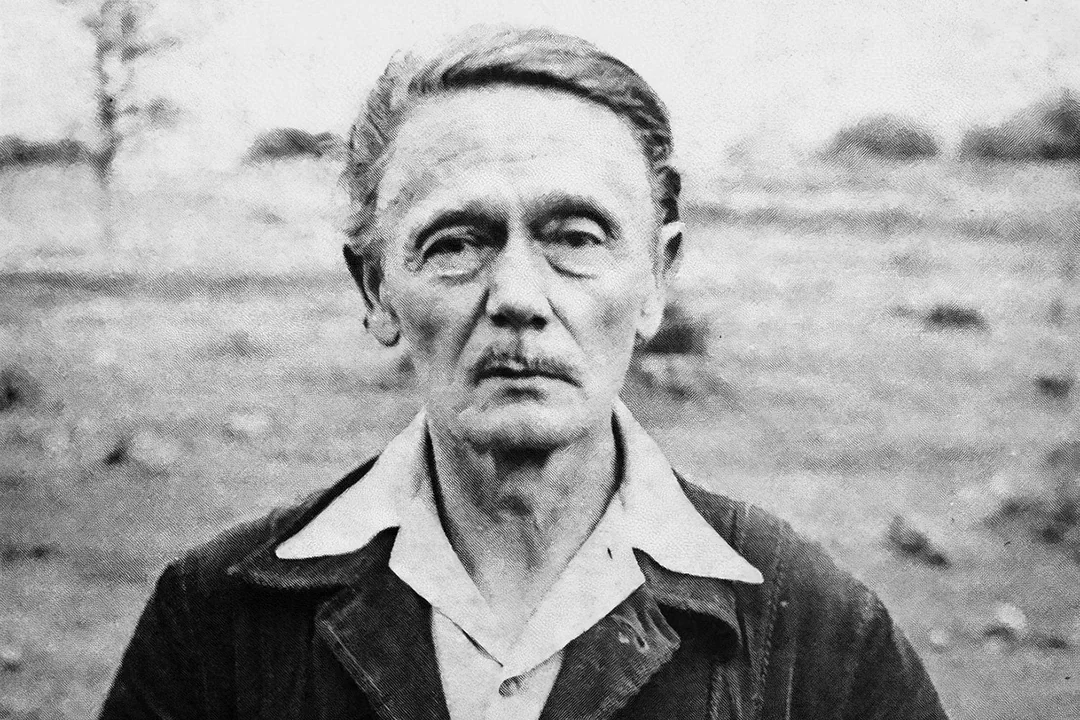

Clark Ashton Smith wrote more than one hundred stories between 1929 and 1937 and then abruptly stopped, returning to poetry as well as painting and sculpture for the rest of his life. Smith lived much longer than his friends and fellow Weird Tales authors Robert E. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft, dying only nine years ago in 1961, but his fiction writing ceased at the same time as theirs.

In his introduction, Lin Carter writes that it's not known why Clark Ashton Smith stopped writing short fiction. However, we can make some educated guesses. Clark Ashton Smith's ailing parents, whose illness had prompted him to turn to writing for the pulp magazines in the first place, died in 1935 and 1937 respectively. What is more, his good friends and correspondents Robert E. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft died in 1936 and 1937 respectively. So Smith no longer needed the money that writing for the pulps brought in and the loss of his friends probably also robbed him of whatever joy writing weird fiction brought him. So he returned to his first love, poetry, and also found new artistic pursuits in painting and sculpture.

Authors who write purely for the money are often referred to as hacks, but nothing could be further from the truth with regard to Clark Ashton Smith. For Clark Ashton Smith always remained first and foremost a poet. Of course, Smith wasn't the only poet to appear in the pages of Weird Tales; his friends and correspondents H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard both wrote poetry, some of which found its way into Weird Tales. But neither of them infused their stories with poetical imagery as much as Smith did. Reading a Clark Ashton Smith story often feels like reading a prose poem from the era of the decadent movement. Smith was an admirer of French decadent poet Charles Baudelaire and even translated his famous poetry collection Les Fleurs du Mal into English.

The Human Thesaurus

My first encounter with the works of Clark Ashton Smith was less than fortunate. It was some twenty years ago, when I had just started corresponding with some American science fiction and fantasy fans. Excited to talk about my favourite books with like-minded people, I expressed my love for the works of Isaac Asimov, Leigh Brackett and Edgar Rice Burroughs. This was a mistake, for my new pen pals immediately let me know in no uncertain words that my taste in science fiction was terrible. Particularly Dr. Asimov elicited scorn for his rather plain and transparent prose.

Meanwhile, one of my new pen pals extolled the virtues of a writer I'd never heard of named Clark Ashton Smith. When I asked about Smith, I was told that I was probably too stupid to understand his work, since I was not a native speaker and therefore couldn't be expected to understand someone as exalted as Smith. Note that the person who said that was the son of immigrants himself and his native language was definitely not English.

With this background, I finally encountered my first Clark Ashton Smith story – which is actually included in Zothique – in the yellowing pages of a vintage issue of Weird Tales. My initial impression was less than favourable. Here was a pretty good horror story smothered in the most overblown language imaginable, almost as if Clark Ashton Smith had swallowed a Thesaurus and now regurgitated the most obscure words possible. Was I too stupid to understand it? No, though I did have to consult my Uncle Nick's Langenscheidt English-German dictionary (full of obscure words, because it's a very old edition) more than usual. At any rate, I let my pen pal know that well, maybe in America it's considered smart to know lots of obscure words and also know how to spell them, but here in West Germany we make fun of people using big words to seem intelligent, because they're very much blowhards.

Of course, Clark Ashton Smith is hardly to blame for the fact that my pen pal was a rude idiot. And as I encountered more of Smith's work, I came to appreciate it better. Smith probably really did swallow a Thesaurus or at the very least he learned one by heart, since he apparently read and memorised every single word in the Unabridged Oxford English Dictionary and the Encyclopaedia Britannica. However, Smith would have had no time for a blowhard like my former pen pal. He didn't use all of those big words to seem smart (he was smart), but because he enjoyed it.

A Clark Ashton Smith story is as much a poem as it is a story. In the introduction, Lin Carter notes that Smith has "one of the most intricate and lapidary prose styles in American literature". Twisted trees become "Laocoons of struggle and torture", mountain springs emit "peak-fed torrents […] become tenuous threads or far-sundered, fallen pools" and "a bloated moon rose red as with sanies-mingled blood, over the wild, racing sea". In the past, I have blasted Lin Carter for tortured prose so purple that it's ultraviolet. Clark Ashton Smith's prose is what Carter was clearly aspiring to.

The Continent at the End of the World

Unlike his fellow Weird Tales writers Robert E. Howard, H.P. Lovecraft, C.L. Moore, Seabury Quinn and others, Clark Ashton Smith's stories rarely had recurring characters – mostly because very few of his protagonists actually survive the end of the story. What Smith did have, however, were recurrent locations such as Hyperborea, a prehistoric world similar to Howard's Hyborian age, Poseidonis, made of the ruins of Atlantis, the fictional French medieval province of Averoigne, most likely adjacent to C.L. Moore's Joiry, and the far-off planet Xiccarph.

Another of Clark Ashton Smith's recurring locations is Zothique, the last remaining continent of Earth in the very far future, when the sun has grown dim and all the continents we are familiar with have sunken beneath the sea. Science and technology have long been forgotten, magic has experienced a resurgence and people live in vaguely medieval vaguely antique worlds. We've seen this vision of the dying Earth of the far future before, in The Book of Ptath by A.E. Van Vogt and The Dying Earth and Eyes of the Overworld by Jack Vance. However, Clark Ashton Smith's Zothique predates all of them.

There is a map of Zothique included in the book, since it is apparently becoming fashionable to include maps in fantasy books. Though you don't really need it, because it doesn't really matter where Naat, Tinarath, Xylac, Cincor and Cyntrom are located, for this not a travelogue.

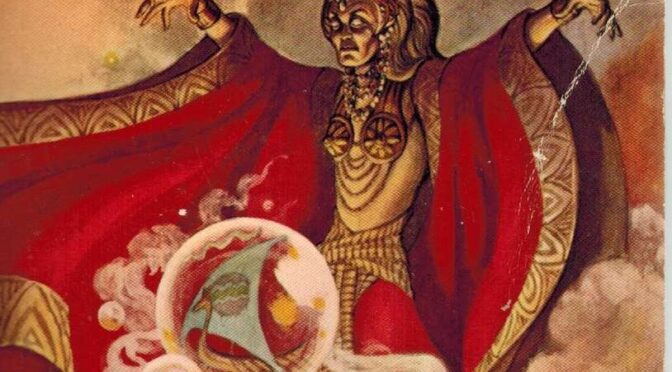

The sixteen stories and one poem that make up this collection are united by an all-pervading sense of melancholia fitting for the end of the world. The German word "Weltschmerz" very much describes the mood and atmosphere of these stories.

The stories themselves are dark, more horror than fantasy, but then Weird Tales did not much care about modern genre boundaries. Many of the stories deal with necromancy and the undead, both in the form of decayed mummies and beautiful women. Indeed, women in Clark Ashton Smith stories are inevitably beautiful, usually lethal and frequently undead such as the titular characters in "The Death of Ilalotha" and "The Witchcraft of Ulua".

There is often an element of poetic justice, whether it involves the necromancers from "The Empire of the Necromancers" who get their comeuppance at the hands of the unwilling and undead victims forced to serve them, or the inhabitants of Uccastrog, "The Isle of the Torturers", practicing their dark art on the sole survivor of a lethal plague. In "The Dark Eidolon", the beggar boy Namirrha becomes a powerful sorcerer to avenge himself on Prince Zotulla whose horses once nearly trampled him to death, only for his vengeance to leave both Zotulla and Namirrha as well as their retainers and the entire city dead. Occasionally, there is a Conan type adventurer such as the trio of Yanur, Grotara and Thirlain Ludoch who break into the tomb of a long-dead king, only to find not untold riches but death in "The Weaver in the Vault". Many stories also have a cyclical element to them such as the tale of "Xeethra" the goatherd who has a vision that he was King Amero of Calyz in a previous life and makes a bargain with an evil deity to become King Amero, only for Amero to long for the simple life of a goatherd in the far future. Or maybe, we are all just character in a storybook anyway, as in "The Last Hieroglyph".

An Acquired Taste

The work of Clark Ashton Smith can be challenging or even off-putting, when first encountered. Reading Deryni Rising and re-reading Zothique in rapid succession was certainly a jarring experience, for after the fairly plain language of Katherine Kurtz, it took some time and a glass of wine or two to reacquaint myself with Clark Ashton Smith's elaborate and poetic prose.

However, Zothique is well worth persevering with, because Clark Ashton Smith was one of the most unique voices in fantastic fiction, a poet who by chance and circumstance ended up writing for the pulps and yet retained his unique voice. I am grateful that Lin Carter and Betty Ballantine have made his work accessible again to modern readers and hope to see more Clark Ashton Smith in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series soon.

Five stars: some of the strangest and most beautifully written stories in all of pulp fiction.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

While I have not read a ton of his fantasy works, I have enjoyed the few SF stories of his I've read — for example "Master of the Asteroid” (1931). Thank you the article. And I love the photo of his cabin.