by John Boston

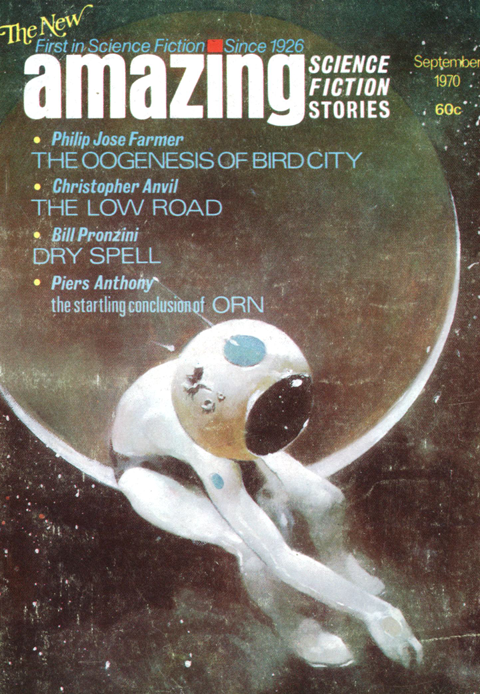

The September Amazing has a new and rather pleasing look. Editor White recently announced that he had wrested control of the magazine’s visual presentation from Sol Cohen and would be using American artists and dropping the former bulk purchases of covers from European magazines. The home-grown covers started a couple of issues ago, and now here is “The New Amazing Science Fiction Stories,” in a new and reasonably attractive type face, over an agreeable cover by Jeff Jones portraying a slightly fuzzy figure in a space suit floating in the void, with a planet almost totally eclipsing its sun in the background. Only problem is that the figure looks a bit like it’s sitting on the inside bend of the thin crescent of light at the edge of the planet, recalling entirely too many cartoonish advertisements of previous decades. Oh well. It still looks nice if you don’t think about it too much.

by Jeff Jones

The departments are as usual, with the book reviews fortunately restored after last issue’s absence. Most notable is Greg Benford’s review of Joanna Russ’s And Chaos Died, which begins: “Reading this, I began to feel that it just might be the best sf novel ever written”; continues: “It is sad, then, to see this marvelous spirit succumb to an escalation of philosophical level the book just can’t support”; and ends: “Novels this ambitious always fail. But it is seldom that you see an artist writing over the heads of 90% of the writers in this field (including me), and it is a welcome sight. This is a great book. Read it.” After that, Dennis O’Neil on The Collected Works of Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, Benford again on Vernor Vinge’s Grimm’s World, and O’Neil again on James Blish’s Star Trek novel Spock Must Die, all seem anticlimactic.

The letter column begins with a different sort of fireworks, with James Blish in at least medium-high dudgeon over editor White’s review of Blish’s Black Easter, which he says “contains so many errors of fact or implication that I must ask you to publish these corrections.” White responds sharply and at length, stating among other things “You have not commented on my principle [sic] charges of dishonesty. . . .” Something tells me we won’t be seeing any more of Mr. Blish in Amazing’s review column, or anywhere else in the magazine. Also notable is a letter from Hector R. Pessina of Buenos Aires describing the SF magazine landscape (rather sparse) in Argentina. In his responses to other letters, White corrects one correspondent: the publisher’s string of SF reprint magazines doesn’t cost money, it makes money to help support Amazing and Fantastic. And in response to SF scholar R. Reginald, he relates the true history of his collaborative pseudonym Norman Archer.

White’s editorial includes comments on the editing of the serial Orn, discussed below, and also on his general policy toward serials—avoid cutting, run them in two parts because of the magazine’s bimonthly schedule (and there’s no plan to take it monthly) and because the point of running them is “to publish important new novels, not to coerce you into buying our next issue.” White thinks “Most modern sf readers . . . want at least one ‘major’ item into which they can sink their teeth. . . . . at least a piece of sufficient length for the author to stretch out and probe his protagonists, and one in which they, as readers, can ‘live’ for a while,” and they want it in chunks large enough to be emotionally satisfying.

Orn, by Piers Anthony

The main attraction of this issue is the conclusion of Piers’ Anthony’s serial Orn, which editor White says is to be published in book form later this year as Paleo. It is a sequel to Anthony’s novel Omnivore, and I am at some disadvantage not having read the latter. White’s editorial says that he did some cutting, with the author’s permission, mostly of material he considered redundant—“If you’ve read Omnivore, you’ve missed nothing.” And the converse, I suspect.

It's the human characters for whom the backstory most matters. They are a team of three agents of a seemingly authoritarian Earth government who in Omnivore were assigned to Nacre, a damp and foggy planet inhabited by sentient aerial fungi who look like manta rays, hence called mantas (though later on they are described as like flying toadstools—go figure). The crew was brought back to Earth and brought some mantas with them, with bad consequences not detailed here.

Now, the humans and mantas are awaiting return to Nacre in a cramped orbiting capsule, until they’re abruptly told they’re going somewhere else, not a “listed” planet but an “alternate” (no elaboration), and they probably will never return to Earth. They’re expected to “make casual survey of its flora, fauna, and, as far as practicable, its mineral resources,” and report back. And they are told “the phase is proper,” which is rare, so step this way right now! Except that three of the mantas fly ahead and attack the people in charge with their dangerous sharp tails for no apparent reason. But never mind, the three humans and the four remaining mantas are hastily shuffled off to the unlisted planet with their supplies.

Well, that’s a lot of contrivance with not a lot of explanation to start out with. But it’s not even Chapter 1. That belongs to Orn, a large flightless bird who hatches only to find that both of his parents have been killed by “reps.” (Animals are all referred to by contractions here—“reps,” “mams,” “aves,” “tricers,” etc.—which is irritating until you get used to it. Or if you don’t.) The author solves the problem of making a newborn bird an interesting character by ringing in that hackneyed device, racial memory, though at least he makes clear that this bird can access only the memories of his own direct ancestors. So Orn, and we, get a capsule postnatal mind-movie of evolution on this very Earth-type planet, and when that’s done, Orn chows down. His father conveniently managed to kill the reptile (a “croc”) that was killing him. So Orn “advanced on the piled meat before him. Flies swarmed up as his beak chopped down. He was hungry, and there was no one else to feed him.” The author delicately avoids the question whether Orn sticks to the dead croc or engages in patriphagy as well.

by Michael William Kaluta

The story proceeds in alternating chapters, one for Orn then one from the viewpoint of a human character (the humans appear in rotation), but none for the mantas. Orn and the humans both learn they are on islands (different ones), and shortly thereafter that the area is seismically active—so much so that they all have to flee an approaching tsunami. The human called Veg (real name Vachel) just happens to have built a nice raft unbeknownst to the others (did I mention contrivance?). So they pile aboard with their stuff, and when the tsunami has passed, they keep going.

So, about these humans. There are three: Aquilon (real name Deborah), a tall blonde woman who is a gifted artist; the aforementioned Veg (Vachel), a physically powerful man; and Cal, a physically small and weak man of great intelligence. Anthony says of them, early on:

“Aquilon loved both men. The physical side of her leaned toward Veg, the intellectual toward Cal. Yet it was Veg’s intellectual example she followed now for she had not eaten meat, fish or fowl since returning to Earth from Nacre. She needed something intangible that she had not been able to find or assess, except that it related to them. And both men believed they needed her—but the truth was that they needed each other, and she was only in the way. They had been good companions before she met them—better than they were now, though neither man spoke of the subtle, insidious change occurring. Could she abscond with Veg’s body and Cal’s mind? Was she selfish enough to interpose her femininity (more bluntly, her femaleness) between them, drawing to herself the life-preserving dialogue that they had for each other?”

This is all alarmingly schematic, but I’m pleased to report that this tell-don’t-show program does not dominate the story going forward.

Meanwhile, back on the raft, they are sailing east and hit California-to-be after a few days. Cal has determined from his study of sea shells that this is in fact Earth, of the Paleocene epoch, dawn of the age of mammals, and everything he sees confirms it. There ensues a pastoral idyll of several days, after which they sail south as autumn commences. I use “idyll” advisedly. The ease with which our heroes rough it in the Paleocene is reminiscent of The Swiss Family Robinson.

Soon enough, the humans come to a warmer, volcanic area, just south of where Baja California will one day be, which turns out to be a rather less idyllic enclave of surviving Cretaceous reptiles.

And Orn has meanwhile been trekking through the same proto-North American continent, facing down the perils of mammalian predators and doing his best to circumnavigate active volcanic zones. He’s moving south to avoid encroaching cold weather and fetches up at the same reptile sanctuary. And he’s also driven by something else—“The thing he had been unknowingly searching for—the nameless mission—the object of his quest”—the spoor of a female of his kind, unbred.

Here things get hot and heavy. Orn is on the scent, literally (“his pumping glands sharpened his senses, and all his memories focused on this one task”). “Days old now, her trail stimulated him exquisitely.” And before long—there she is. Ornette! Among other charms: “Her wings were well-kept and handsome, looking larger than they were because of the unusual, almost regressive length of their primaries. Her tail, too, had sizable retrices, and the coverts displayed the grandeur of the nuptial plumage.”

But first the chase! “Then she was away, whirling her shapely sternum about and running from him; and he was running after her with all his strength. . . . This was the way it was meant to be, and had been, throughout the existence of the species.” It all takes a while, but the ending is foretold: nest-building followed by consummation followed by eggs.

by Michael William Kaluta

And now the humans are on to Orn. They’ve seen his footprints, and the mantas are reporting his and Ornette’s existence (which by the way refutes their belief that they are on a younger Earth).

At this point, philosophy (always lurking) rears its head. The humans have been uncomfortable about reporting back to the Earth authorities, and discovering that this world is not the prehistoric Earth but some sort of parallel world—perhaps one of a multitude—results in a full-blown schism, with Cal supporting opening it for human colonization. Veg and Aquilon disagree, and walk out, finding a spot not far from the birds’ nest, spreading a tarp and affirming their solidarity in the usual human fashion. Cal sets off in the raft to their supply cache for the radio to contact Earth, and acts out his let-the-best-species-have-it-all ideology in an absurd but successful encounter with a tyrannosaurus (Tyrann, of course). Hearing of this from the mantas, Veg heads off to help Cal, knocking Aquilon down when she suggests otherwise. Aquilon saves the birds and one of their eggs from an earthquake and a crocodilian attack, and is invited—nay, commanded—to join their family. But in the end, tragedy and defeat come to them all.

Notice I didn’t say coherent philosophy. A small example: not surprisingly, one of the motifs carried over from the previous book is the distinction among herbivores, carnivores, and omnivores, with the last category having come (at least in Aquilon’s mind) to signify humanity’s rapacious appetite for—well, everything. Cal points out that Orn, the noblest character in the book, was also an omnivore. “That isn’t what I meant!” she responds. (The rest of the exchange: “You’re being emotional rather than rational.” “I’m a woman!”)

So this isn’t a novel to read for its intellectual qualities, other than evidence of considerable reading-up on paleontology (including an odd “Postscript” purporting to be Cal’s report on Paleo). The author’s preference for unconstrained Nature over the ravages of civilization is made quite clear, and the noble savage Orn is the most sensible character in the book. But it’s a very eventful novel, especially towards the end, and as a piece of agreeable storytelling, it comes across reasonably well. Three and a half stars.

The Oogenesis of Bird City, by Philip Jose Farmer

The lead story in the issue, by the biggest name on the contents page, is “The Oogenesis of Bird City” by Philip Jose Farmer, which the editor’s blurb explains is a repurposed outtake (“effectively the prologue”) from Farmer’s Hugo-winning novella “Riders of the Purple Wage.”

Oogenesis, if you’ve forgotten, means the biological process by which female gametes (ova) form and mature within the ovaries. What actually goes on in the story is the ultimate urban renewal. The President of the US is making an appearance at the ribbon-cutting of the said City, which consists of hyper-modern egg-shaped houses on a platform 20 feet high, built over an existing poor neighborhood in Los Angeles. These houses are to be given free to the winners of a first-come, first-served sign-up, and once they’re moved in everything else will be free too! (Hence Bird City—everybody will be free as a bird!)

by Michael Hinge

This is the opening wedge for a program to reform the entire society—ORE, for “obverse-reverse economy,” which will:

'

“ . . . split the economy of the nation in half. One half will continue operating just as before; that half will be made up of private-enterprise industries and of the taxpayers who own or work for these industries. This half will continue to buy and sell and use money as it has always done.

“But the other half will be composed of GIP’s [guaranteed income people], living in cities like this, and the government will take care of their every need. The government will do this by automating the mines, farms, and industries it now owns or plans on obtaining. It will not use money anywhere in its operations, and the entire process of input-output will be a closed circuit. Everybody in ORE will be GIP personnel, even the federal and state government service, except, of course, that the federal legislative and executive branches will maintain their proper jurisdiction.”

Shazam! Let’s all remind ourselves not to have SF writers design our utopias.

All this is set out in hectic and cartoony fashion, as irritating as it is superficial, and let’s not even bother with the racial politics. Two stars; the author at least had an idea, even if it’s a bad one.

The Low Road, by Christopher Anvil

And oh no, it’s Christopher Anvil, back again after the leaden levity of that ponderous morality tale "Trial by Silk" a few issues ago. This one is a sequel to "Bill for Delivery," from Analog back in 1964. It is right in the mainstream of Anvil’s work, i.e., it sets a silly and contrived problem and provides a jokey solution. The problem here is that the crew of a cargo spaceship discovers it is carrying a big load of “intellectual stimulators,” contraband devices which enhance and focus the cognitive abilities of people within their range on particular specialized matters (here, calculus) to the exclusion of all else, like self-preservation. These devices tend to go off spontaneously, and if there are many of them the effects are cumulative, and human exposure will likely become fatal with time.

by Dan Adkins

Now, the cargo modules are attached to the spaceship by “spider lines,” and they are at some distance from the ship (otherwise the story would already be over), but they have to be drawn in close when the ship starts up, which means the crew will become exclusively preoccupied with calculus and won’t be able to perform their duties. Solution: disable them from calculus! So everybody gets drunk and dis-calculused, but can still perform their menial tasks of operating the spaceship. Two stars, barely, and could we trade this in and get Ensign Ruyter back?

Dry Spell, by Bill Pronzini

Bill Pronzini’s "Dry Spell" is a slight vignette about a blocked writer who finally gets an idea but it proves self-defeating, literally. Two stars—it’s well-wrought trivia.

Mr. Bowen’s Wife Reduces, by Miles J. Breuer

This issue’s “Famous Amazing Classic,” from the February 1938 issue, is Miles J. Breuer’s “Mr. Bowen’s Wife Reduces.” Breuer is one of the earliest contributors of original work to Amazing, starting with the January 1927 issue, and published a number of substantial works there and elsewhere for the next decade. This is not one of them, though it’s a clever variation on one of the genre’s great cliches.

The small, fastidious Mr. Bowen is dissatisfied with his wife, who has put on a great deal of weight (now at 220 pounds) and isn’t too bright either. He sees a lawyer who refers him to a doctor, and his wife submits willingly to his prescription: “Substance recently isolated from a gland in certain animals. . . . Injection once a week.” So she starts to lose weight—but all over, and doesn’t stop, gets tiny, and one day can’t be found.

Fearing a murder charge, Mr. Bowen flees to the mountains. He comes upon the estate of a chain-store magnate he has met who once suggested he drop by for some pheasant hunting, and who welcomes him and invites him to stay indefinitely. He hits it off with one of the seemingly resident ladies, a Mrs. Bowman (nothing is said about any Mr. Bowman). After many enchanted evenings, he declares his love—and then he wakes up. More precisely, he emerges from his delusional state to find himself in a mental hospital, with his slim wife waiting for him, having been treated for hypothyroidism in his . . . absence. Three stars, well enough done for what it is.

What You Eat You Are, by Greg Benford and David Book

This issue’s “Science in Science Fiction” article is “What You Eat You Are,” by Greg Benford and David Book, a departure from their usual sort of subject matter, but not their usual style of high-density lucidity. This one is a no-words-wasted tour of what humans eat, why only certain substances work as food, how our nutritional systems evolved, the absurdity of expecting human nutritional requirements to be satisfied by what we happen to find on other planets, the importance of trace elements, how to (try to) design an artificial ecology for an extraterrestrial environment and why those efforts might fail, the necessity of tracing all inputs and outputs through their varied paths through an ecosystem, and an outline of a proposal for an agricultural system for space pioneers (vegetarian, for good reasons). And by the way, we can’t go back to that here on Earth, even if we wanted to, and the available alternatives are all pretty bleak in different ways. Whew! Four stars.

Summing Up

The editor has delivered on his promise of something in the issue long enough for readers to “sink their teeth into,” but unfortunately the rest of the fiction mostly leaves the reader snapping at the air. Well, could be worse. In fact, it has been. Let’s not think about that.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

Like John, I mostly enjoyed "Orn." It has its problems, but for the most part it's a decent read. Ted White is correct that whoever told Anthony he needed human characters was wrong. A story just about Orn would have been fine; those were the best bits anyway.

I didn't like "Purple Wage" at all, and I didn't care for this prologue either.

Time was Chris Anvil showed signs of being a decent writer. Those days are long gone (I blame Campbell). It also looks like Dan Adkins has started copying Mad Magazine.

I couldn't remember a single thing about "Dry Spell" and had to go get my copy of Amazing. At least it was very short. And I'll probably forget the whole thing again by the time a drop this missive in the mailbox. Fitting, I suppose.

I didn't think much of the classic, either. While it only works in a magazine where one expects fantastic elements, there's nothing sfnal in it at all. John liked it better than I did.

And an excellent science article. Every SF writer and reader ought to study it thoroughly and take its lessons to heart.