by Jessica Dickinson Goodman

Giant worms and spacefaring spice addicts in Frank Herbert's Dune introduced many genre readers to the fantastical potential of vaguely Islamic-themed fictional settings. But there's so much more to the real-life worlds and cultures he lightly touched on, so many more exciting, complex, beautiful places writers could be taking us.

Take Yemen.

The mouth of the harbor sits at the bottom a giant volcanic rock face, the black stone caldera soaring up around it on 3 sides. For centuries, the 53 Cisterns of Tawila held nearly a million gallons of water for the port city of Aden. Generations used these deep, carefully engineered pools to not only manage monsoon seasons that would break and slide over the volcanic cliffs surrounding the city, but provide a bustling community with fresh, clean water even in the hottest months.

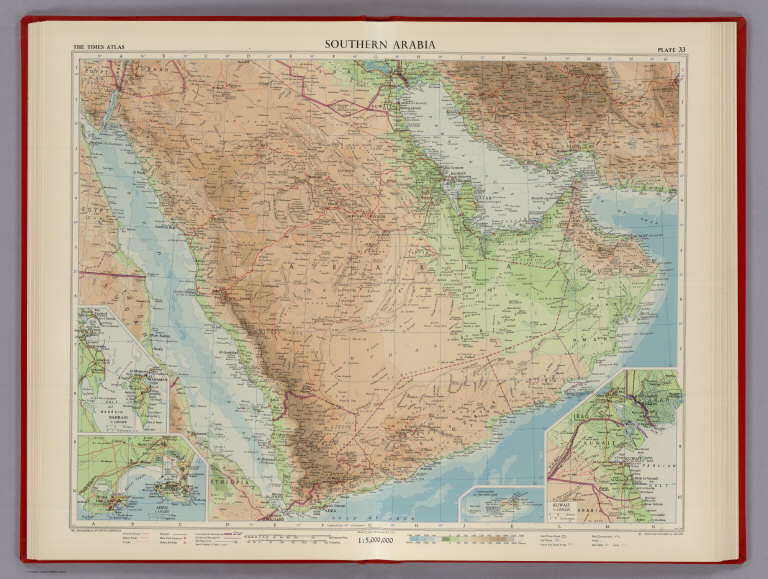

Travel north, past Queen Asma (?-1087 CE) and Queen Arwa (1048–1138 CE)'s great palaces and you can find the Marib Dam, from which people used successfully to irrigate 25,000 acres of farmable land 2000 years ago. Keep going east to the city of Shibam and you'll find skyscrapers over 10 stories tall, made from what this Californian could call adobe bricks, one and two room floors connected by sudden staircases and adorned by sweet little balconies. During your travels, you'll hear a local language influenced by a dozen indigenous languages, with a healthy smattering of the best bits of various invaders' tongues. The food is hot and plentiful, the oases well-loved, the stars unending, the many mountains steep, and the local politics as complex as any you've followed. Just off the coast is an island where most of the plants and animals exist nowhere else in the world and hold names like "Worm Snakes" and "Dragon's Blood Trees."

To me, this setting begs for a novel or a TV series. Frank Herbert or Stanley Kubrick, are you listening?

Write Beyond What You Know

The problem is, outside Frank Herbert and the sadly departed Cordwainer Smith, our fantasy and fantastic SF all tend to be written by people who know nothing but the European historical tradition. Any overly optimistic writer who tells a stranger she enjoys writing fiction will probably hear the advice to "write what you know." And this can be true for internal beats, for emotions, for arcs and compelling endings. But when writer after writer sets novel after novel, episode after episode, in the same gloomy castles, writes knights riding the same bridled horses over the same musty moats to fight the same stale dragons, I think this old advice has turned into a trap. And what's worse, it's a trap that reinforces a European-centric view of the world, of history, of culture, and when used in science fiction, of the future.

It's been close to a century since anyone in my direct family called Europe home, but still, when I was growing up and I imagined writing a fantasy, the setting was staffed by maidens fair and knights gallant. That frustrating limitation on my own imagination is why I started to travel in college and after, why I learned Arabic and bits of Hebrew, Spanish, French, and enough Japanese to sound-out street signs in Japantown in San Francisco or San José. I particularly enjoy traveling to the Middle East, to Doha and Ramallah and Gaza, to Muscat and Cairo and Istanbul.

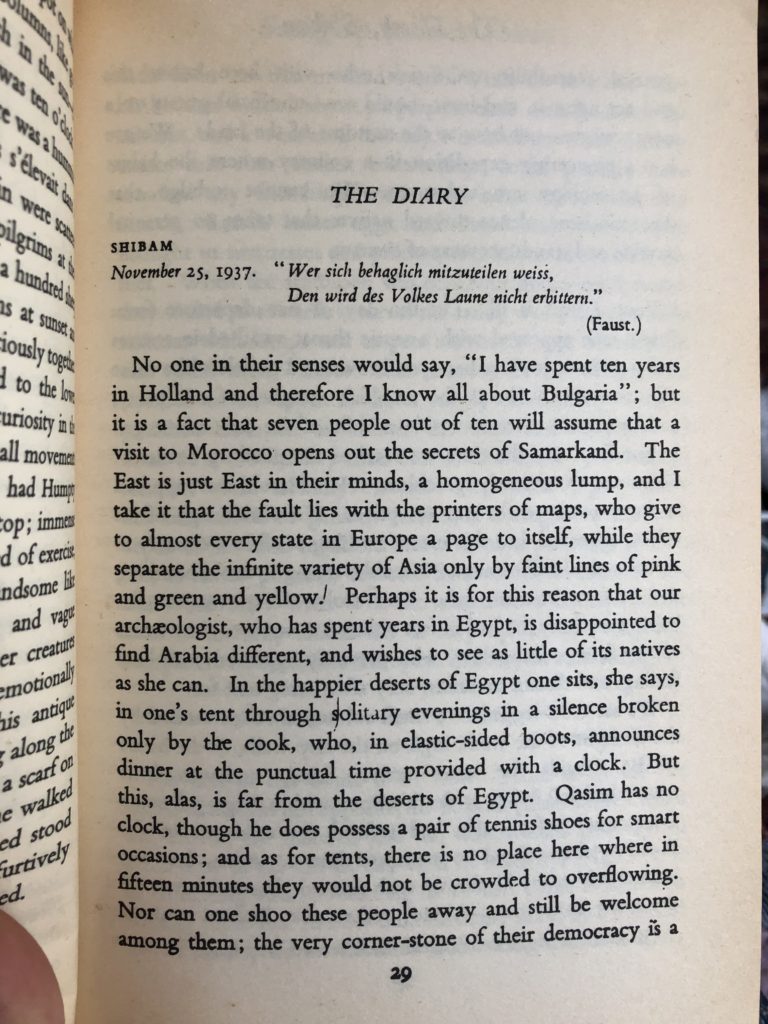

I'm not the first western woman writer to be curious about the Middle East, or to travel alone through large parts of it. From 1937-1938, 44-year-old British-Italian travel writer Freya Stark spent a winter in Yemen and wrote a detailed, sympathetic, hilarious diary about it titled, as one might expect, A Winter in Arabia. She went to the port city of Aden, to Queen Arwa's palace, to the mud-built skyscrapers of Shibam. She went out into the world to know more about it, and then she wrote what she knew. Like any good writer, she didn't try and own or warp the cultures she saw, but tried to tell the truth, as she saw and understood it. She had little patience for people who did less.

The same ignorances she highlighted 30 years ago still infect most people's understandings of the region. A friend might read about one country's struggles in the newspaper, and assume they know about every other country. Even worse, they might hear about a conflict between two countries and assume that conflict encompasses the whole of what there is to be known about both countries. It would be a bit like someone being taught United States history and having their first fact about us be that we're a country in conflict with Cuba. And that is part of who we are, but it is certainly not all of it; and there are many perspectives on that topic, particularly within Cuban American communities. As writers, we have the opportunity to see more, to learn more, not just passively, but actively – to learn more about the world so we can write more about it.

The few Americans who know anything about Yemen today tend to know about Operation Magic Carpet, where from 1949-1950 American and British airlines worked tirelessly to help about 49,000 Yemenite Jews from Yemen and nearby countries get to Israel after they faced credible threats of violence and some actual violence from their neighbors and states. The discrimination those Yemenite Jews have faced in Israel has been less well-publicized, but is worth understanding, as well as the the way that Mizrahi Jewish people (those who moved or fled to Israel from Middle Eastern and North African countries) view and understand their own histories of diaspora differently than Sephardic, Ashkenazic, or Ethiopian Jews.

Yemen is a Kosher Topic

I'll pause here. Most Americans have a big ball of complicated emotions in their chests about Israel, the U.S. relationship to Israel, the relationships between Israel and her neighbors, and the future of the region. Some have very simple emotions, for good or ill; some don't care at all. Many Christians I grew up with don't know any more than they were taught in Sunday school. But the gravitational force that Israel exerts on most conversations about the region is something anyone curious about the Middle East must come to contend with.

That's why I like learning about Dhū Nuwās, 13th ruler of the Jewish Kingdom of Ḥimyar in Yemen in the 500s. The Himyarite Kingdom had had Judaism as its de facto state religion for over a century at that point. The Byzantine Emperor, Justin I asked Ma'dīkarib Yafur, the ruler of the Christian Kingdom of Axum in Ethiopia to invade Yemen and overthrow Dhū Nuwās.

Talk about a setting for a fantasy novel. No musty moats or drippy castles, this story has armies crossing the stormy Bab al-Mandab Strait; it has intrigue as we don't know who started the war or why. It has oasis cities razed to the ground; transnational alliances from Constantinople to Ethiopia; countries in the throes of mass conversion; and tragedy, as Dhū Nuwās is overthrown and the ruler of Axum takes over in Yemen. It has real people, widows and soldiers, farmers and fishermen, people who carved the stone steles which tell us this story and people who had to find a new way to preserve their faith in spite of the rulers who took over.

Fantastic Yemen

Whether your tone as a writer is epic or epistolary, intensely personal or wide-sweeping, there are just as many stories to tell in this tiny slice of Yemeni history as there are in any given year of the War of the Roses or the Battle for Agincourt. And as readers, we can demand to see these kinds of stories. We can write to our magazines and ask for a view beyond what the BBC World Service is willing to provide. And when we find stories that satisfy our freshly whetted palates, we can share and recommend them.

Reading and writing fantasy and science fiction that respectfully includes the people and places in the Middle East isn't going to end the North Yemen Civil War, nor address the Soviet Union, Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom, or Jordan's encouragement of it, nor Egypt's heavy commitment of ground troops to it. But I believe that learning and writing and reading teaches us empathy, teaches us to question, so when the nightly news asks us to accept violence or hatred as a region's due, we know that's just not true. We know there are histories and complexities beyond "centuries of conflict." We have a right to learn, to help ourselves and our communities better understand the world and our place in it. And perhaps, help to build a more peaceful world. Not to mention, enrich our fantasy and science fictional worlds!

Bibliography

If you're curious about this region, below are a few recommendations – and I would love to hear more from readers if you have them!

- A Winter in Arabia, by Freya Stark.

- Enjoy some Yemenite folk music (your local record store should have Mohamed Al-Harithy and Geula Gill discs or be able to order them from the label)

and

- Consider subscribing to some magazines that will bring in-depth, alternate views on current affairs. I like Foreign Affairs for a sense of what government leaders want me to think, Jewish Currents for what leftists want me to think, and The Economist for what capitalists want me to think.

- Reach out to your local mosque, or if you don't live near one, find one in a nearby city. Ramadan starts on August 25th this year, and many masjids may open their doors for community dinners. Get to know your neighbors and ask them what newspapers they think you should subscribe to to learn more about the region.

- Then share that knowledge with your friends and write to learn!

![[May 18, 1967] After Dune (the fantastic setting of Yemen)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/5443721933_cce05bca34_b-672x372.jpeg)