by Kaye Dee

Despite the hiatus in manned spaceflight missions while the Apollo-1 and Soyuz-1 accident investigations continue, October has been a very busy month for space activities – so much so that I’ve had to defer writing about some of this month’s events to an article next month!

Spaceflight Slowdown?

4 October saw the tenth anniversary of the launch of Sputnik-1, the Soviet satellite that surprised the world and ushered in the Space Age and the Space Race. Since that first launch, the pace of space exploration has been breathtaking, far surpassing what even its most ardent proponents in the 1950s anticipated.

In the famous Colliers’ “Man Will Conquer Space Soon” article series, reproduced even here in Australia, Dr Wernher von Braun predicted that the first manned mission to the Moon would not occur until the late 1970s

As part of the USSR’s Sputnik 10th anniversary celebrations, many space-focussed newspaper articles were published. One of these, written by Voskhod-1 cosmonaut and engineer Dr. Konstantin Feoktistov, strongly hinted that Russia's next major space feat would be the launch of an orbiting space platform. This would certainly be an important development in establishing a permanent human presence in space and put the Soviet Union once again ahead in the Space Race, especially if the US and USSR lunar programmes are faltering.

Earlier this month, the head of the NASA, Mr James Webb, said it was increasingly doubtful that either the United States or the Soviet Union would land people on the Moon in this decade. He delivered a gloomy prognostication for the second decade of the Space Age, saying the entire US programme was “slowing down”. Mr. Webb criticised recent Congressional cuts of 10 per cent to the space-agency budget projected for the year ending next 30 June, saying that NASA was laying off over 100,000 people.

Administrator Webb also cast doubt on some proposed NASA planetary exploration missions. “The serious question is whether or not this country wants to start a Voyager mission to Mars in 1968”, he is reported to have said. The Voyager programme is a 10-year project that envisages sending two spacecraft to Mars (one to orbit around it, the other to land on its surface), with the additional possibility of landing a spacecraft on Venus and exploring Jupiter. These would undoubtedly be exciting missions that would reveal new knowledge about these planets, but Mr Webb said he had virtually no money for the Voyager programme as a result of the budget cut.

Parallel Planetary Probes: Venera-4 and Mariner-5

But possible future downturns in space activity can’t detract from this month’s big news: the safe arrival of two spacecraft at Venus!

Back in June, a suitable launch window meant that both the USSR and NASA sent spacecraft on their way to our closest planetary neighbour. First off the blocks was the Soviet Union, which launched its Venera-4 mission (generally known in the West as Venus-4) on 12 June from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. NASA’s Mariner-5 followed two days later, on 14 June, launched from Cape Kennedy.

Pre-launch photo of Venera-4

Venera-4 is the most recent Soviet attempt to reach the planet after Venera-2 and 3 failed to send back any data in March last year. There is some speculation that, since its previous Venus mission employed twin spacecraft, Russia may have also intended this Venus shot to be a two-spacecraft mission. It’s possible that the short-lived Cosmos 167 spacecraft, launched on 17 June, was Venera-4’s twin that failed to leave orbit, although with the secrecy that surrounds so much of the Soviet space program, who knows if we’ll ever get the truth of it? Venera-4 was itself first put into a parking orbit around the Earth before being launched in the direction of Venus. A course correction was performed on 29 July, to ensure that the probe would not miss its target.

Mariner-5 being prepared for launch

Mariner-5 is NASA’s first Venus probe since Mariner-2 in 1962. Originally constructed as a backup for the Mariner-4 Mars mission, that probe’s success meant that the spacecraft could be repurposed to take advantage of the 1967 Venus launch window. Interestingly, I understand from my friends at the Sydney Observatory that there were initial suggestions to send the Mariner back-up spacecraft to either comet 7P/Pons–Winnecke or comet 10P/Tempel, before the Venus mission was decided upon. While it’s useful to have additional data from Venus, it would have been fascinating to send an exploratory mission to a comet, since we know so little about these transient visitors to our skies.

At its closest, Venus is just 36 million miles from Earth, but Mariner-5 followed a looping flightpath of 212 million miles, to enable it to fly past Venus at a distance of around 2,500 miles (about 10 times closer than Mariner-2’s flyby). Australia’s Deep Space Network (DSN) stations at Tidbinbilla, near Canberra, and Island Lagoon, near the Woomera Rocket Range, were respectively the prime and back-up monitoring and control stations for Mariner-5’s mid-course correction burn that placed it on its close flyby trajectory.

Keys to Unlock a Mystery

Venus has always been a planet shrouded in mystery since its thick, cloudy atmosphere prevents any telescopic observation of its surface. For this year’s launch window, one could almost believe that Cold War tensions had been overcome and the USSR and USA had agreed to work together on a Venus exploration program, given that their two spacecraft effectively complement each other.

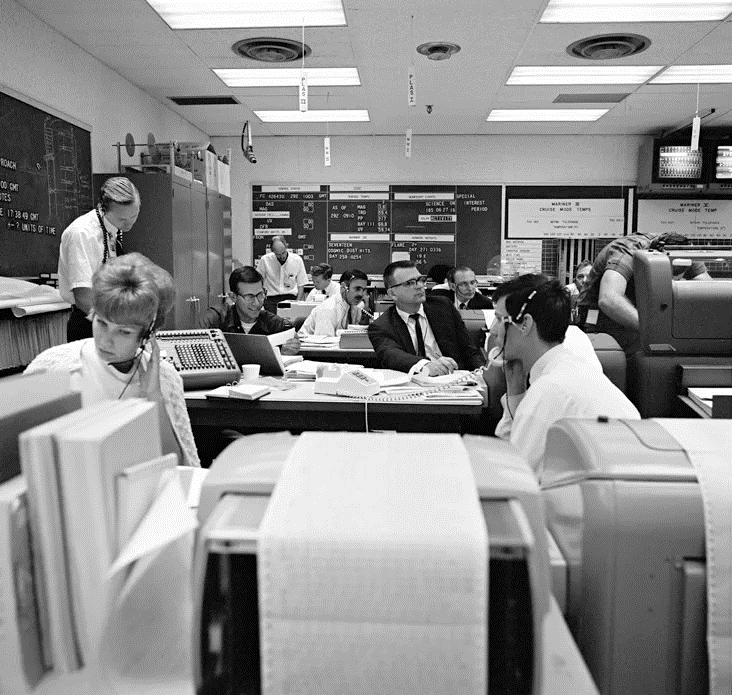

Venera-4’s mission was announced as “direct atmospheric studies”, with Western scientists speculating that this meant that it would follow Venera-3 in attempting to land on the planet’s surface. The spacecraft’s arrival at Venus has proved this speculation to be correct, and the few images of Venera-4 now available show the 2,436 lb spacecraft to be near-identical to Venera-3. 11 ft high, with its solar panels spanning 13 ft, Venera-4 carried a 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) spherical landing capsule that was released to descend through the atmosphere while the main spacecraft flew past Venus and provided a relay station for its signals.

Soviet models of the Venera-4 spacecraft and its descent capsule

Soviet models of the Venera-4 spacecraft and its descent capsule

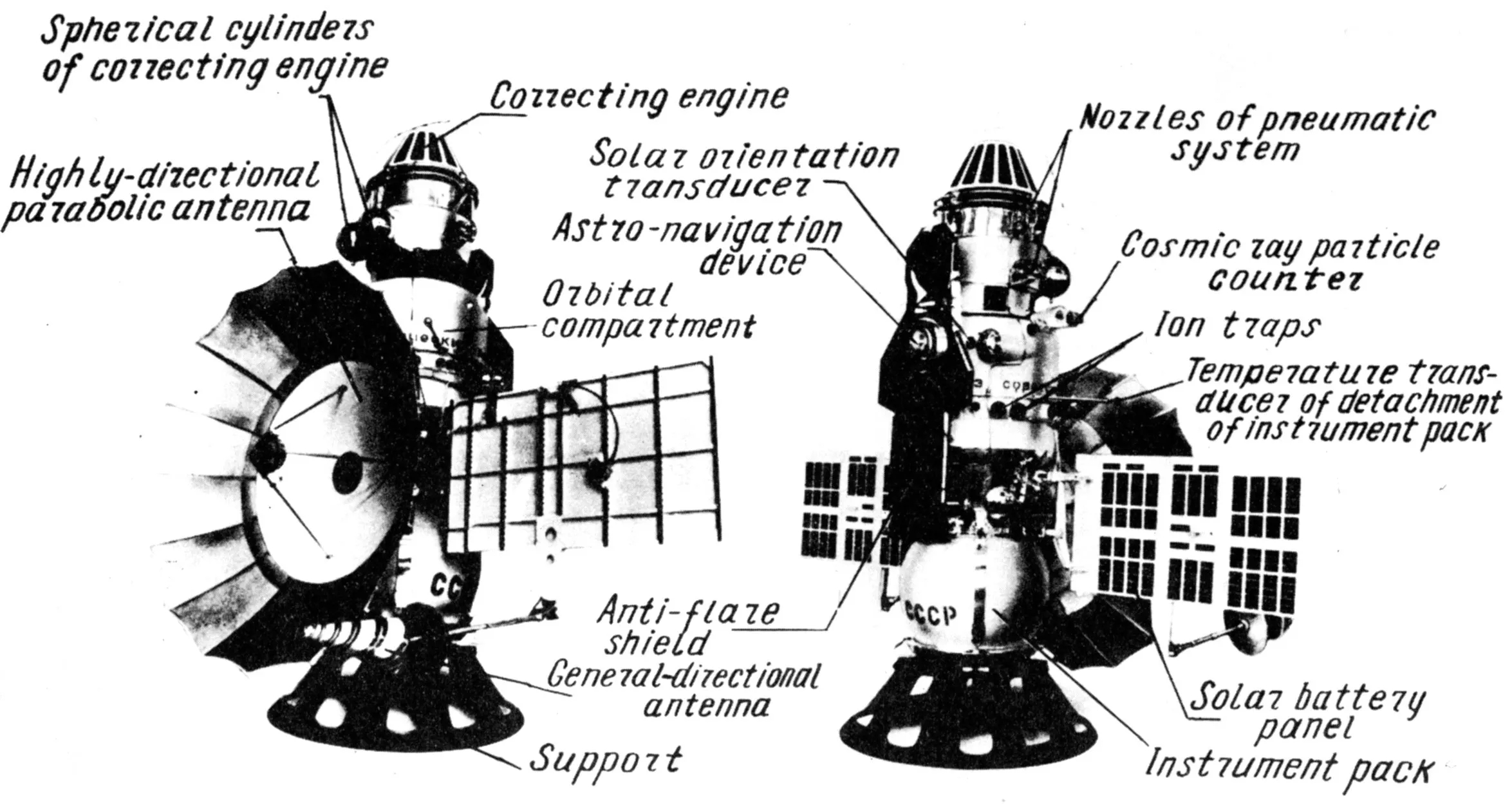

The 844 lb descent capsule was equipped with a heat shield, capable of withstanding temperatures up to 11,000°C (19,800 °F) and had a rechargeable battery providing 100 minutes of power for the instruments and transmitter. During the flight to Venus the battery was kept charged by the solar panels of the carrier spacecraft. Supposedly, the entire Venera-4 probe was sterilised to prevent any biological contamination of Venus, but some Western scientists have cast doubt on this claim. The capsule was pressurized up to 25 atmospheres since the surface pressure on Venus was unknown until Venera-4’s arrival.

Picture of the Venera-4 descent capsule released by the USSR. Western scientists are wondering what that heat shield is made of

Picture of the Venera-4 descent capsule released by the USSR. Western scientists are wondering what that heat shield is made of

Information recently released by the Soviet Academy of Sciences has said that the descent vehicle carried two thermometers, a barometer, a radio altimeter, an atmospheric density gauge, 11 gas analysers, and two radio transmitters. Scientific instruments on the main body of the spacecraft included a magnetometer and charged particle traps, both for measuring Venus' magnetic field and the stellar wind on the way to Venus, an ultraviolet spectrometer to detect hydrogen and oxygen gases in Venus' atmosphere, and cosmic ray detectors.

Much smaller than Venera-4, the 5401b Mariner-5 was designed to flyby Venus taking scientific measurements: it was not equipped with a camera, as NASA considered this un-necessary in view of the planet’s cloud cover. NASA controllers initially planned a distant flyby of Venus, to avoid the possibility of an unsterilised spacecraft crashing into the planet, but the final close flyby was eventually chosen to improve the chances of detecting a magnetic field and any interaction with the solar wind.

As Mariner-4’s backup, Mariner-5 has the same basic body – an octagonal magnesium frame 50 in diagonally across and 18 in high. However, since it was heading to Venus instead of Mars, Mariner-5 had to be modified to cope with the conditions much closer to the Sun. Due to its trajectory, Mariner-5 needed to face away from the Sun to keep its high-gain antenna pointed at Earth. Its solar panels were therefore reversed to face aft, so they could remain pointed at the Sun. They were also reduced in size, since closer proximity to the Sun meant less solar cells were needed to generate the same level of power. Mariner-5's trajectory also required the high-gain antenna to be placed at a different angle and made moveable as part of the radio occultation experiment. A deployable sunshade on the aft of the spacecraft was used for thermal control, and Mariner-5 was fully attitude stabilized, using the sun and Canopus as references.

View from below showing the main components of Mariner-5

View from below showing the main components of Mariner-5

Mariner-5’s prime task was to determine the thickness of Venus’ atmosphere, investigate any potential magnetic field and refine the understanding of Venus’ gravity. Its suite of instruments included: an ultraviolet photometer, a two-frequency beacon receiver, a S-Band radio occultation experiment, a helium magnetometer, an interplanetary ion plasma probe and a trapped radiation detector. The spacecraft instruments measured both interplanetary and Venusian magnetic fields, charged particles, and plasmas, as well as the radio refractivity and UV emissions of the Venusian atmosphere.

During its 127-day cruise to Venus, Mariner-5 gathered data on the interplanetary environment. In September and October, observations were co-ordinated with measurements made by Mariner-4, which is on its own extended mission, following its 1965 encounter with Mars. Similar observations were made by Venera-4 during its flight to Venus, which found that the concentration of positive ions in interplanetary space is much lower than expected.

Missions Accomplished

A few days before it arrived at Venus, the Soviet Academy of Sciences requested assistance from the massive 250 feet radio telescope at the Jodrell Bank Observatory in the UK, asking the facility to track Venera-4 for the final part of its voyage. This has provided Western scientists with some independent verification of Soviet claims about the mission. Jodrell Bank even announced the landing of the Venera-4 descent capsule more than seven hours before it was reported by the Soviet news agency Tass!

On 18 October, Venera-4’s descent vehicle entered the Venusian atmosphere, deploying a parachute to slow its fall onto the night side of the planet. According to a story that one of the Sydney Observatory astronomers picked up from a Soviet colleague at a recent international scientific conference, because there was still the possibility that, beneath its clouds Venus might be largely covered by water (one of the main theories about its surface), the capsule was designed to float if it did land in water. Uniquely, the spacecraft’s designers made the lock of the capsule using sugar, which would dissolve in liquid water and release the transmitter antennae in the event of a water landing.

On 18 October, Venera-4’s descent vehicle entered the Venusian atmosphere, deploying a parachute to slow its fall onto the night side of the planet. According to a story that one of the Sydney Observatory astronomers picked up from a Soviet colleague at a recent international scientific conference, because there was still the possibility that, beneath its clouds Venus might be largely covered by water (one of the main theories about its surface), the capsule was designed to float if it did land in water. Uniquely, the spacecraft’s designers made the lock of the capsule using sugar, which would dissolve in liquid water and release the transmitter antennae in the event of a water landing.

Although the Venera-4 capsule had 100 minutes of battery power available and sent back valuable data as it fell through the atmosphere, Jodrell Bank observations, and the official announcement from Tass, indicated that the signal cut off around 96 minutes. While it was initially thought that this meant that the capsule had touched down on the surface, and there were even early reports claiming it had detected a rocky terrain, questions are now being raised as to whether it actually reached the surface, or if the spacecraft failed while still descending. Tass has said that the capsule stopped transmitting data because it apparently landed in a way that obstructed its directional antenna. A recording of the last 20 seconds of signal received at Jodrell Bank was delivered to Vostok-5 cosmonaut Valery Bykovsky during a visit to the radio telescope on 26 October. Perhaps once it is fully analysed, the question of the capsule’s fate will be clarified. Of course, if the landing is confirmed, Venera-4 will have made history with the first successful landing and in-situ data gathering on another planet.

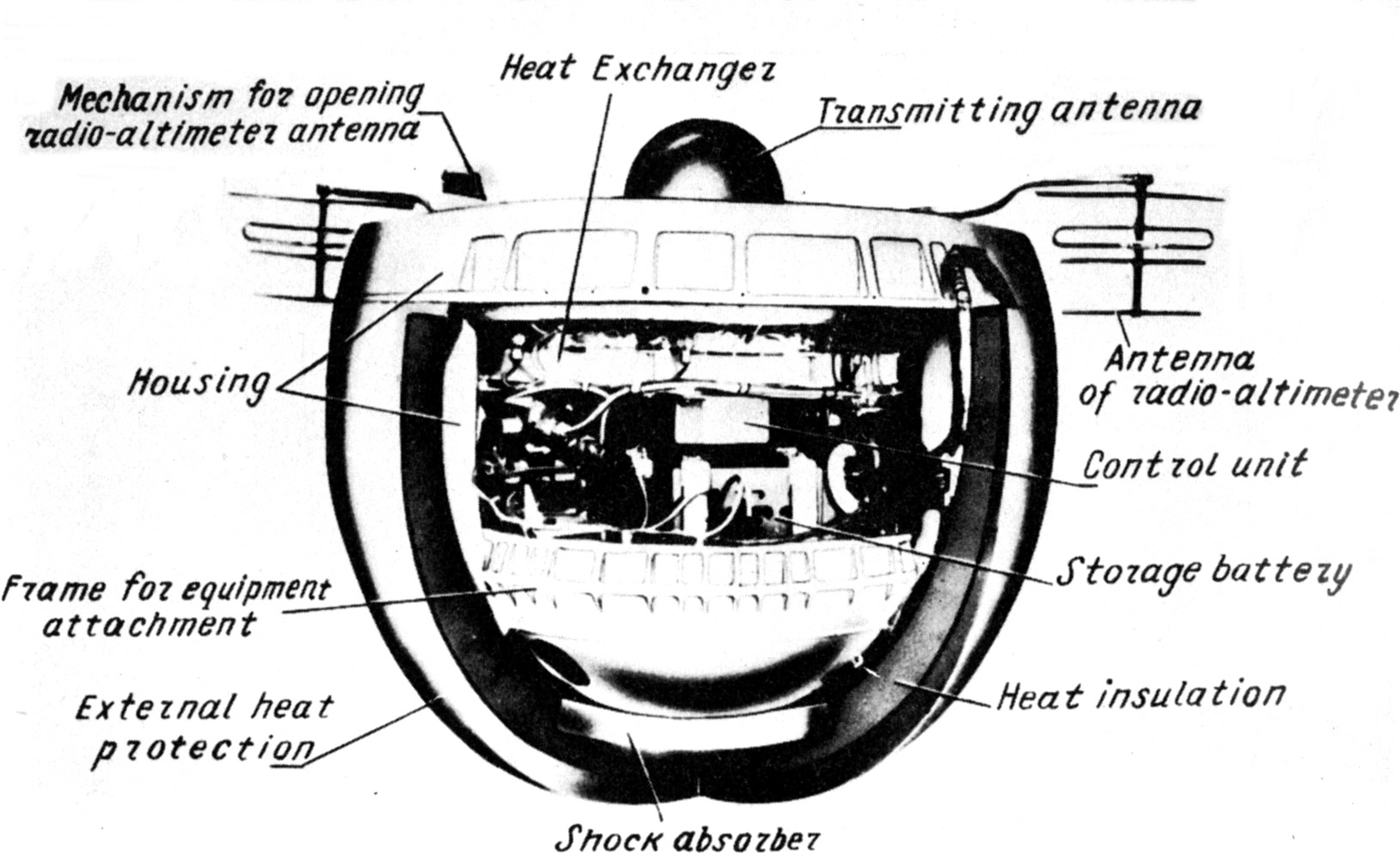

Diagram illustrating the major milestones during the Mariner-5 encounter with Venus on 19 October

Diagram illustrating the major milestones during the Mariner-5 encounter with Venus on 19 October

Mariner-5 swept past Venus on 19 October, making a close approach of 2,480 miles. At 02:49 GMT the Island Lagoon DSN station commanded Mariner 5 to prepare for the encounter sequence and 12 hours later its tape recorder began to store science data. Tracked by the new 200 in antenna at NASA’s Goldstone tracking station, Mariner reached its closest encounter distance at 17:35 GMT, and minutes later entered the “occultation zone” before passed behind Venus as seen from the Earth. 17 minutes later, Mariner-5 emerged from behind Venus and completed its encounter at 18:34 GMT.

The following day, Mariner-5 began to transmit its recorded data back to Earth. Over 72½ hours there were three playbacks of the data to correct for missed bits. Mariner-5's flight path following its Venus encounter is bringing it closer to the Sun than any previous probe and the intention is for to be tracked until its instruments fail.

A Peep Behind the Veil

So what have we learned about Venus from these two successful probes? There has long been controversy among astronomers as to whether Venus is a desert planet, too hot for life, or an ocean world, covered in water. The data from both Venera and Mariner has come down firmly on the side of the desert world hypothesis.

Astronomical artist Mr. Chesley Bonestell's 1947 vision of a desert Venus

Astronomical artist Mr. Chesley Bonestell's 1947 vision of a desert Venus

The effects of Venus’ atmosphere on radio signals during Mariner-5’s occultation experiment have enabled scientists to calculate temperature and pressure at the planet's surface as 980°F and 75 to 100 Earth atmospheres. These figures disagree with readings from Venera 4 mission, which indicate surface temperatures from 104 to 536°F and 15 Earth atmospheres’ pressure, but both sets of data indicate a hellish world, with little evidence of water and an extremely dense atmosphere.

Venera has established that Venus’ atmosphere consists almost exclusively of carbon dioxide with traces of hydrogen vapour, very little oxygen, and no nitrogen. Mariner-5's data indicates that the atmosphere of Venus ranges from 52 to 87 per cent carbon dioxide, with both hydrogen and oxygen in the upper atmosphere: it found no trace of nitrogen. It detected about as much hydrogen proportionately as there is in the Earth's atmosphere. Mariner scientists, however, have pointed out that further analysis and refinements of both Russian and American data could clear up the apparent discrepancies.

Although Mariner’s instruments could not penetrate deeply enough into Venus’ atmosphere to obtain surface readings, they determined that the outer fringe of the atmosphere, where atoms were excited by direct sunlight, had a temperature of 700°F, below which was a layer close to Zero degrees, lying about 100 miles above the surface. Chemicals in the atmosphere, or electrical storms far more intense than those of Earth, give the night side of the planet an ashen glow.

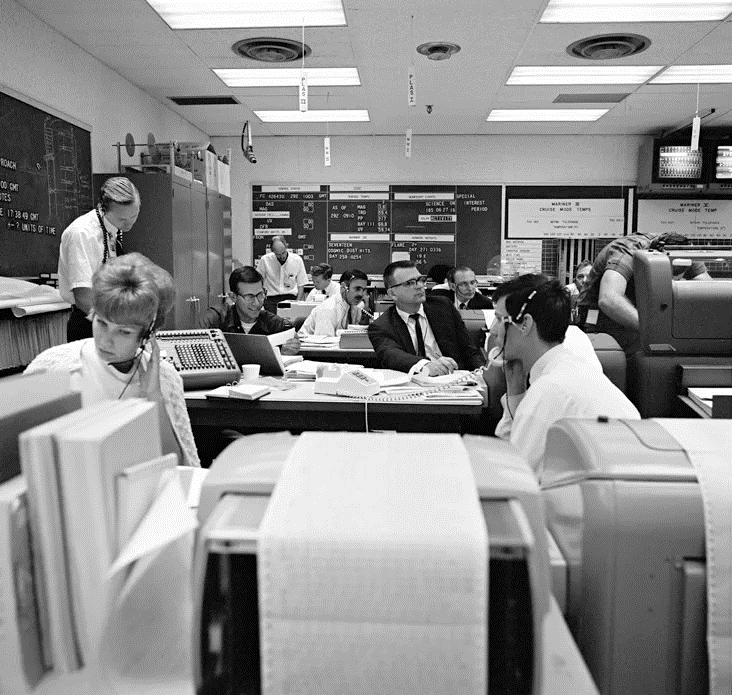

A view of the Mariner-5 control room at JPL during the Venus encounter

A view of the Mariner-5 control room at JPL during the Venus encounter

A fascinating finding is that the dense atmosphere acts like a giant lens, bending light waves so they travel around the planet. Both American and Russian researchers agree that astronauts standing on the surface would feel like they were “standing at the bottom of a giant bowl”, with the back of their own heads a shimmering mirage on the horizon. Vision would be so distorted that the sun would appear at sunset to be a long bright line on the horizon: its light could penetrate the atmosphere, but not escape because of scattering, so that it would appear as a bright ball again for a time at sunrise until the atmosphere distorted its rays.

Neither spacecraft found any evidence of radiation belts comparable to the Van Allen belts around the Earth, and both established that Venus has only a very slight magnetic field, less than 1% that of the Earth. Observing how much Venus' gravity changed Mariner 5's trajectory established that Venus’ mass is 81.5 % that of Earth. Tracking of radio signals from Mariner-5 as it swept behind Venus, has shown that the planet is virtually spherical, compared with Earth's slightly pear-shape. (Other celestial mechanics experiments conducted with Mariner-5 obtained improved determinations of the mass of the Moon, of the astronomical unit, and improved ephemerides of Earth and Venus).

Life on Venus?

Although neither spacecraft was equipped to look for life on Venus, their findings will undoubtedly contribute to the growing scientific controversy over whether life does, or can, exist there. Based on its Venera results, the Soviet Union has said that Venus is “too hot for human life”, although Sir Bernard Lovell, the Director of Jodrell Bank Station, has suggested that future probes might find remnants of some early organic development, even if conditions today make life highly unlikely. However, German/American rocket pioneer and space writer Dr Willy Ley, has suggested there might be the possibility of “a very specialised kind of life on Venus”, possibly at the poles, which he believes would be cooler that the currently measured temperatures. The USSR’s Dr Krasilnikov has said that Earth bacteria could withstand the atmospheric pressure on Venus and might even be able to survive the intense heat.

But just as Mariner-4 demolished fantasies of canals made by intelligent Martians, so the results from Venera-4 and Mariner-5, in allowing us a glimpse behind its cloudy veil, have swept aside any number of science fiction visions of Venus. Edgar Rice Burroughs’ verdant Amtor, with its continents and oceans, and Heinlein’s swampy Venus are no more. They have been replaced by a new vision of a hellish Venus, almost certainly inimical to life, with fiery storms raging in a dense, metal melting atmosphere which traps and bends light waves in a weird manner. I wonder where the SF writers of the future will take it?

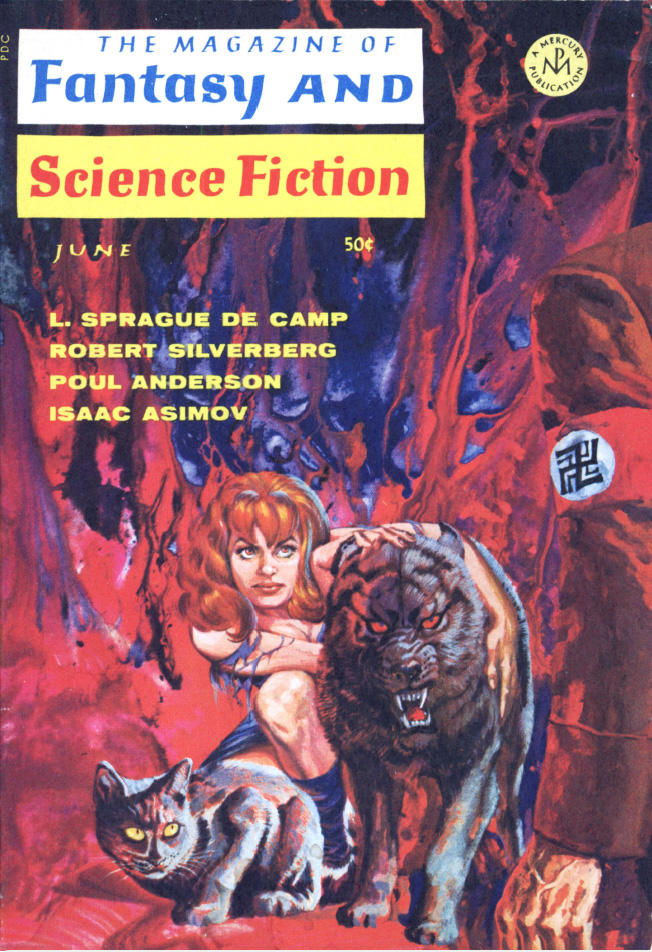

![[May 20, 1969] Ad Astra et Infernum (June 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/690520coverfsf-652x372.jpg)

![[October 28, 1967] Unveiling Venus – at Least a Little (Venera-4 and Mariner-5)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Venus-desert.png)