by Gideon Marcus

Red Venus?

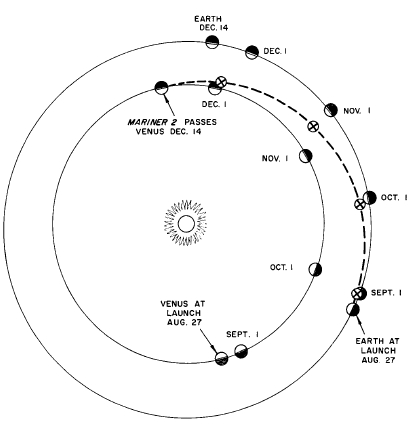

Every 19 months, Venus and Earth reach positions in their trips around the Sun such that travel to the former from the latter uses a minimum of energy. Essentially, a rocket blasts off and thrusts itself toward the Sun just long enough to drift inward and meet Venus after about half an orbit (a direct path would be very costly in terms of fuel use). The less energy used, the bigger the spacecraft can be sent. That means more payload for experiments.

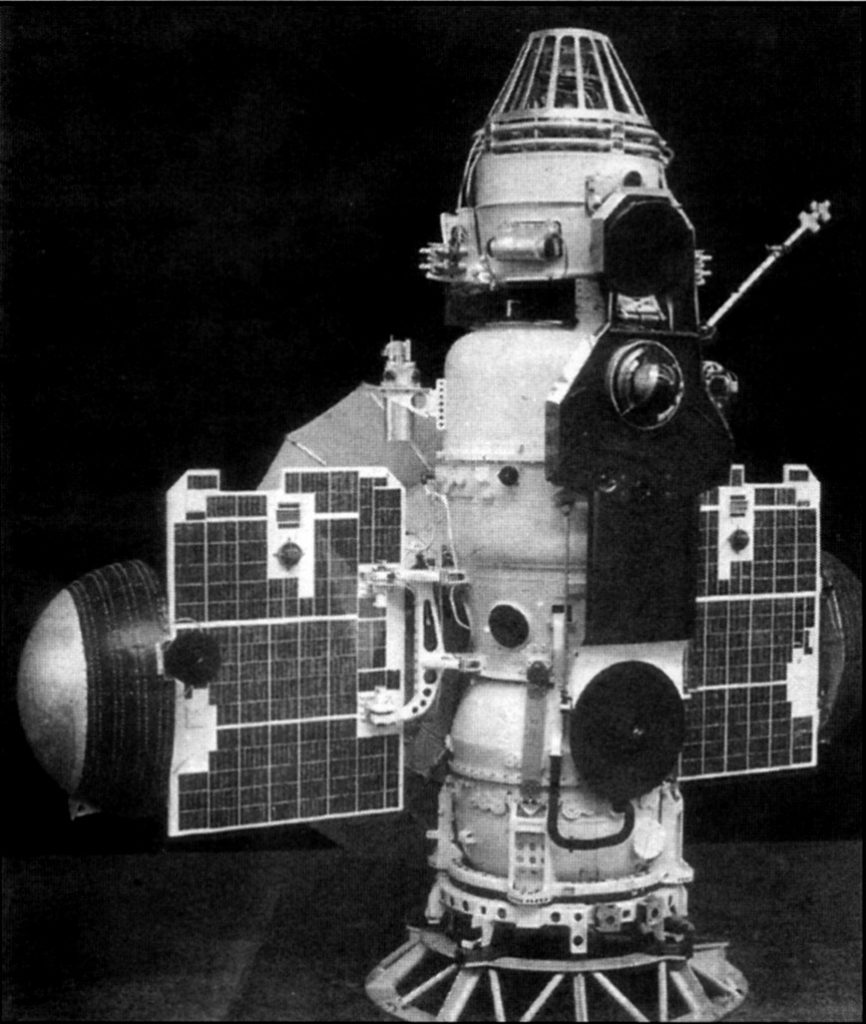

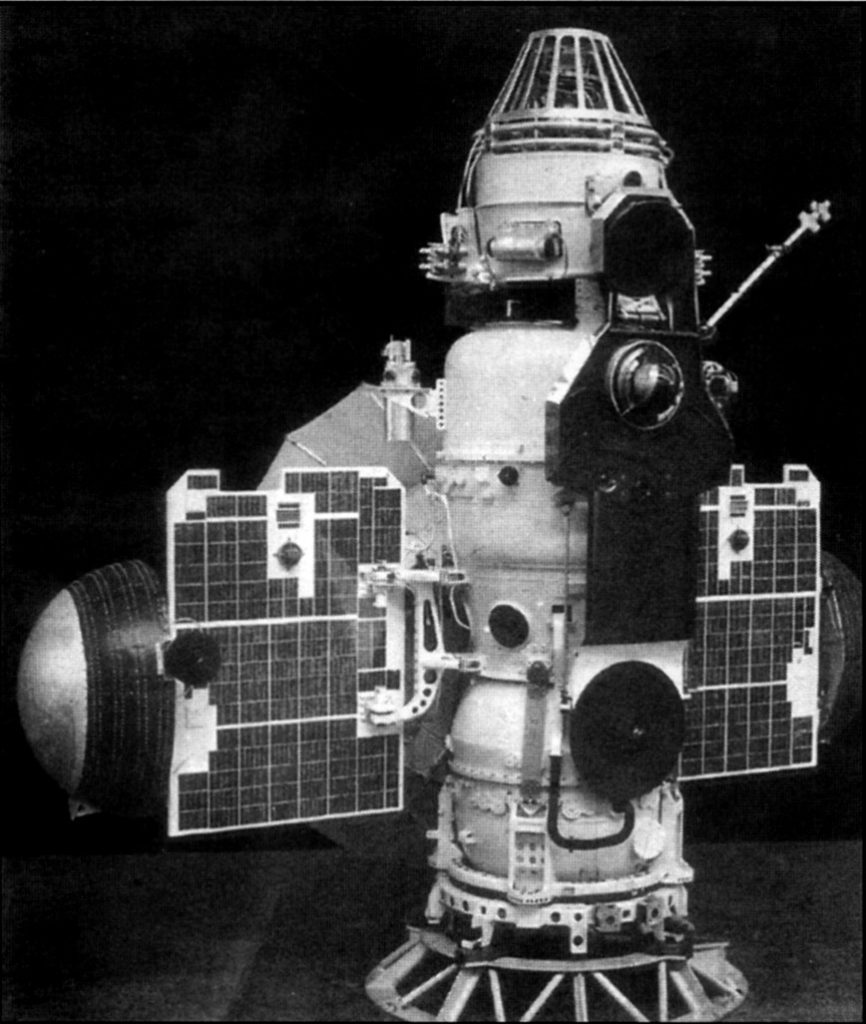

The Soviets have been trying to reach the Planet of Love, Earth's closest neighbor (besides the Moon) for more than six years now. In February 1961, they launched Venera 1 (Venus 1), the first interplanetary probe to fly by another world–but it had gone silent by the time it got there. Veneras 2 and 3 went up three opportunities later, in November 1965, but fell silent the next spring, just before reaching their target. Indeed, Venera 3, a soft-lander, is believed to have rammed the cloud-shrouded world, becoming the first artificial object to reach another world. Either way, no useful data was received.

Why didn't they launch any Veneras in 1962 or 1964? In fact, it looks like they did. The Soviets don't herald their failures. Nevertheless, according to NASA officials, we have a pretty good catalog of them, thanks to careful parsing of Russian news reports as well as radar and telemetry data we've managed to gather. Three Russkie Venus probes were launched in September 1962 and three more in February 1964. Getting out of Earth orbit can be tough, requiring a second firing of onboard engines once a spacecraft is circling our planet. Apparently, these six probes never got away.

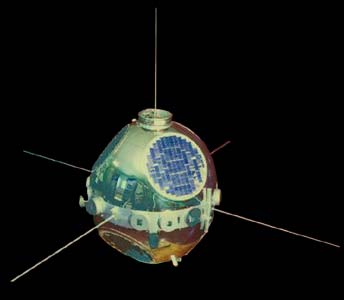

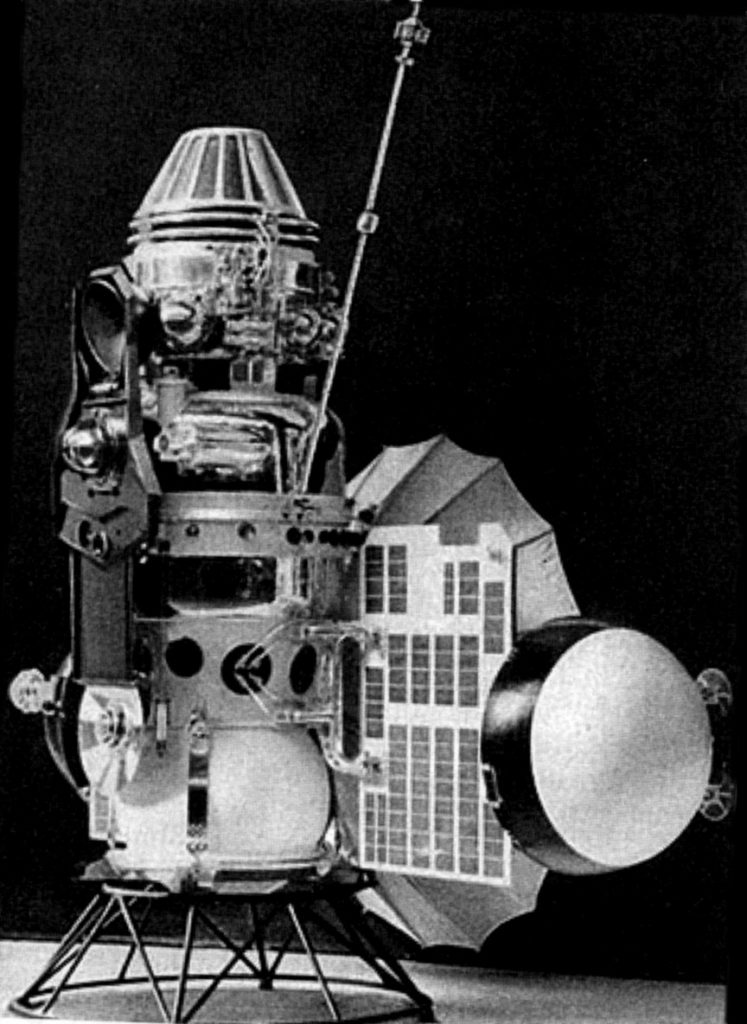

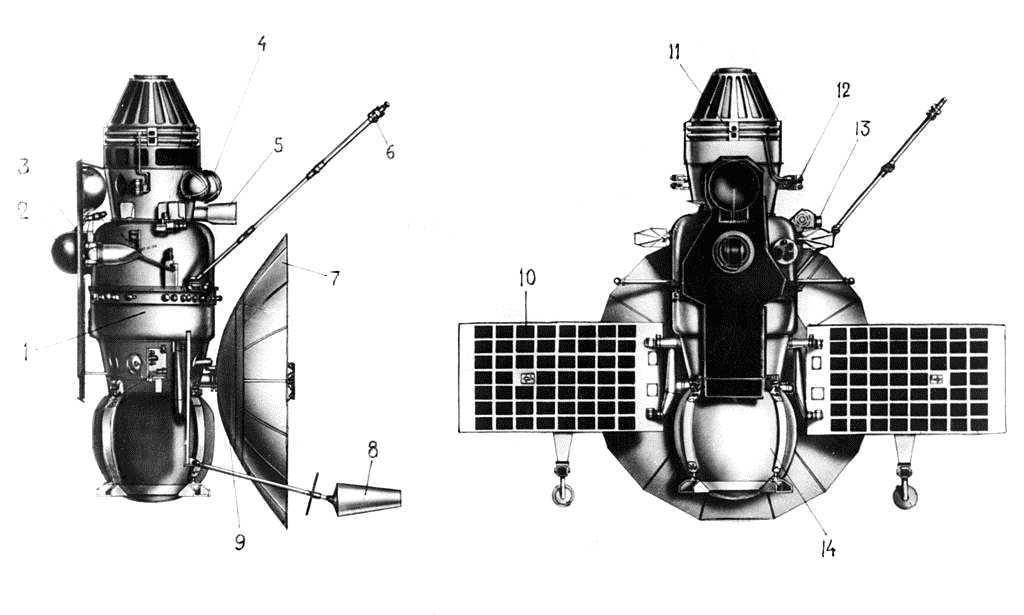

But Venera 4, launched on June 12, 1967, has apparently passed that first hurdle. Moreover, at one and a quarter tons, it is several hundred pounds heavier than any of its predecessors. We don't know much about what's on the latest Communist probe, but scientists speculate some of the extra weight has been devoted to heat shielding. Venus is very hot, perhaps 900° Fahrenheit, and it is believed that heat is what caused Venera 3 to fail. Given that TASS, the Soviet news service, reported that Venera 4 is going to Venus, rather than by, it is assumed the spacecraft will make another landing attempt.

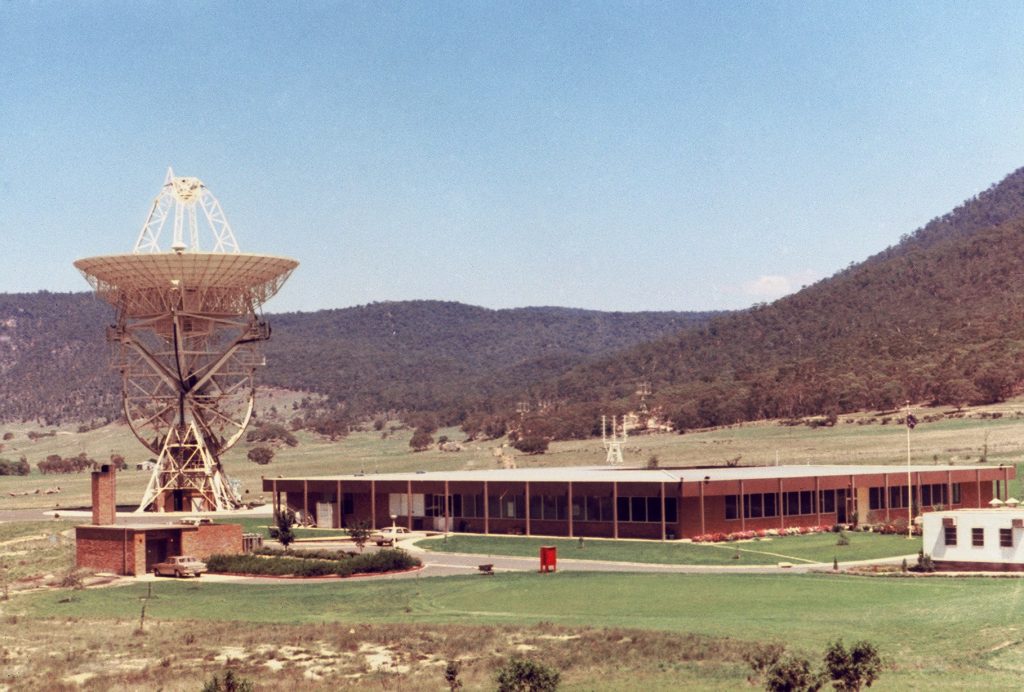

Provided it doesn't go slient like its predecessors. Communicating across planetary distances is a hurdle the Soviets only recently surmounted with their Zond 3 probe, which tested radio reception at about 150 million kilometers' distance–far enough for a Martian mission. Essentially, Zond 3 was the Soviet version of Pioneer 5–but five years later. This is suggestive as to the Soviet level of communications technology, at least. America would seem to have the clear lead there.

Well, I wish the Soviets luck. Politics or no, I want to know more about that mysterious, seared world that is Venus!

Yankee Two-dle

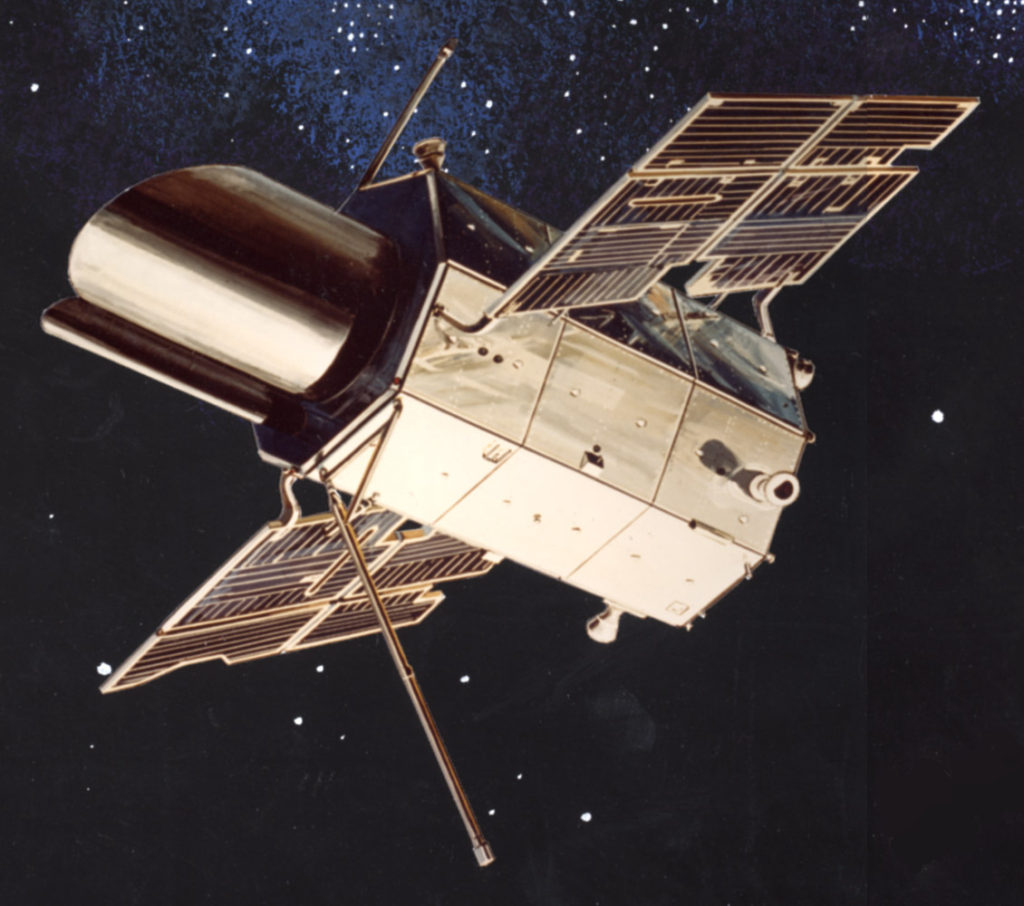

If Venera 4 fails, it has a back-up of sorts. Mariner 5, itself a back-up for the Mars-bound Mariner 4, was launched today early this morning, destination: Venus.

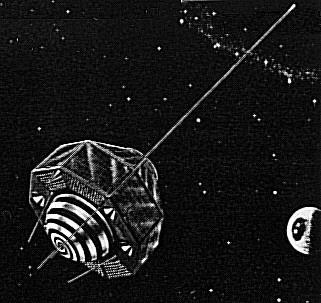

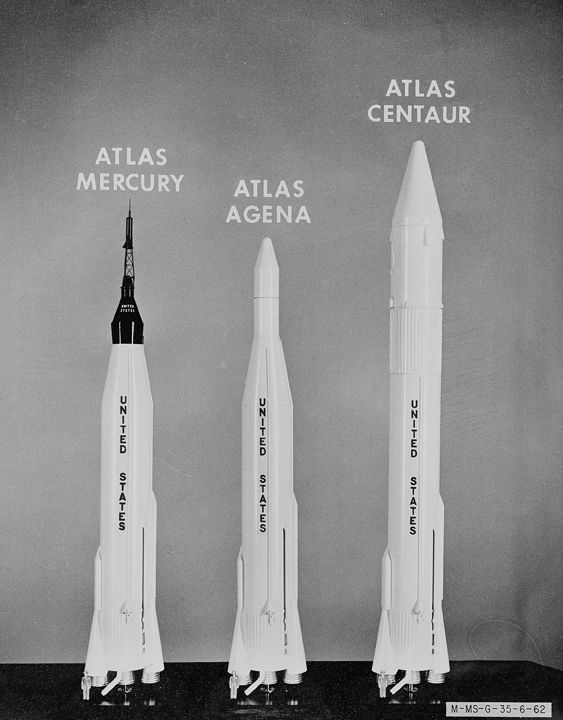

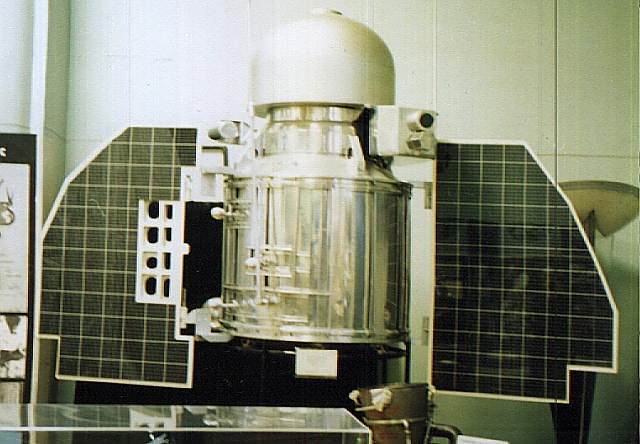

Already several hundred thousand kilometers from Earth, zooming at more than 10,000 kilometers per hour, it should reach Venus in October. The spacecraft, launched via Atlas-Agena, the same rocket that launched our first Venus probe, Mariner 2, is barely a quarter the mass of Venera 4. Moreover, Mariner 4's TV camera has been deleted, a decision that likely irks Venus scientist Dr. Carl Sagan, who insists doing so is short-sighted, clouds or no.

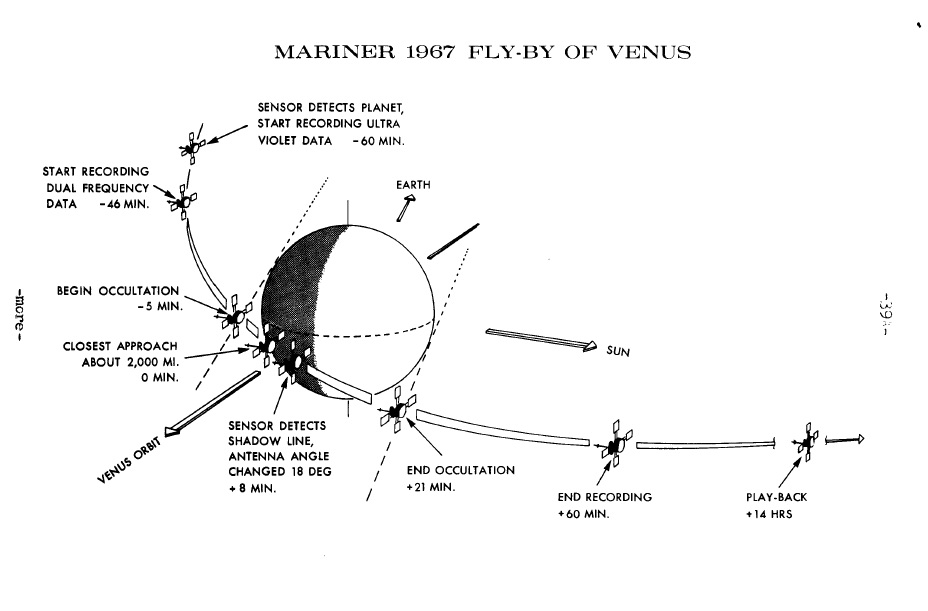

But that removal, along with the reduction in the size of the solar panels (less is needed so close to the sun) means that when Mariner 5's planned flight path brings it within 3000 kilometers of Venus, it will be able to investigate the planet with a wide suite of instruments. An ultraviolet photometer should not only refine temperature estimates of the Venusian upper atmosphere, it will tell us a bit about what gasses constitute it. For instance, if there be any water there, perhaps life exists in the cloud tops, above the intense heat at the surface.

The rest of the instruments are likely ho-hum for the general audience, but should return a bonanza for scientists. They include a magnetometer and various radiation sensing equipment that not only will measure the Venusian version of the Van Allen Belts (if they exist–Mariner 2 couldn't find any), but also tell us a lot about the solar wind on the way to Venus.

I will say, I'm glad we're sending a craft to Venus, and it does seem we did it on the cheap ($35 million), but I think I'm with Sagan on this one: for all the effort, it seems we're not going to find out very much about Venus with Mariner 5. Another reason to root for Venera 4.

And a good reason to write your Congressman about the importance of planning a bigger Venus shot, perhaps on the more powerful Atlas Centaur rocket, when the next opportunity rolls around in January 1969!

Want to find out what we currently know about Venus? Come read our previous articles on the planet of love!

![[June 14, 1967] What's Easy for Two (<i>Venus 4</i> and <i>Mariner 5</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/670614mariner-672x372.jpg)

![[April 20, 1966] Space Exploration is Hard (Venera 2 and 3, Luna 10 and OAO 1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Luna-10-FDC-672x372.jpg)

![[November 22, 1965] Keep on Exploring (Explorer-29 and 30 and Venera-2 and 3)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Venera_2-672x372.jpg)