by Gideon Marcus

Missing Something

Science fiction and fantasy are closely aligned genres. Indeed, there is no hard line between them (like the continuum from sharks to rays) and one person's "soft" science fiction is another's fantasy. Each of the monthly SFF mags has carved out its own turf in the spectrum between hardest SF and fluffiest fantasy.

Analog has chosen the firmest of grounds, its stories highly scientific; even the recent Lord D'Arcy tales are a kind of highly rigorous fantasy. Galaxy, IF, and Worlds of Tomorrow also hew solidly to "reality". The magazines that trip more fantastic tend to indicate such in their titles: Fantastic, Science Fantasy, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

The name of the last one belies the fact that precious little, if any, science fiction appears within its covers these days. It didn't used to be so; during the Mills era, Naked to the Stars, and many other definitive science fiction works appeared. But ever since Avram Davidson took over, and even though he has been gone two issues now, F&SF has been a horror/fantasy mag.

And this is a problem. While SF is an ever-evolving genre, powered by new discoveries that unlock entire subgenres, fantasy is an unstructured, amorphous mass. And horror is (at least for now) a pile of cliches. Seen five Alfred Hitchcock Presents (the TV analog to F&SF) and you've seen them all. You may enjoy those five very much, but after a season of them, you're through with the genre.

F&SF's all-starring January 1965 issue is chock full of stories that might have been passable, if lesser, tales back in 1949. These days, they are frustratingly inadequate, especially given the new 50 cent price tag.

Exibit F (for Fantasy/Failure)

by Mel Hunter (depicting a landing on Neptune's moon, Triton — the closest this issue will get to SF)

End of the Line, by Chad Oliver

We start with an "after the Bomb" piece, which I guess qualifies it as a low form of SF. However, its premise is sheer fantasy. In brief, it is centuries down the line, and civilized humanity has lost the ability to breed. The more comfortable we become, the lower our fertility, the sicklier are our children. Only the ignorant savages outside the last City remain fecund.

One City-dweller is a throwback, leading raiding parties into savage lands to kidnap children to be raised back at home. Whence come this spark of atavistic vigor? Of course, it turns out he's a kidnapped savage. And also that the primitives, themselves, are descendants of City-dwellers abandoned as children. Because all it takes to regain the spark of life is utter deprivation.

It's a dumb story, and women are portrayed as neurotic wives and would-be wet nurses.

Two stars.

Dimensional Analysis and Mr. Fortescue, by Eric St. Clair

Margaret St. Clair (and as her alter ego, Idris Seabright) is one of the best known names in the genre. Her husband, Eric, is an up-and-comer. Unfortunately, his latest story, about a fellow who opens a funhouse but finds it was inadvertently equipped with an interdimensional rift, is a down-and-goer. Just too broadly written and inconsequential; the kind of frothy stuff Davidson dug. Meringue can be tasty, but you can't live on it.

Two stars.

Begin at the Beginning, by Isaac Asimov

The Good Doctor's article is on calendar year system. Entertainingly spun, and including a few tidbits I had not been hitherto aware of, it nevertheless is a history lesson rather than a scientific piece. That's okay, as far as it goes, but it's much easier to present a non-technical piece for a layman than to explain an abstruse topic.

Three stars.

The Mysterious Milkman of Bishop Street, by Ward Moore

Turn-of-the-Century fellow engages a new milkman who promises to deliver his goods right to the doorstep rather than let it freeze on the street. The product is superb, the service excellent — too excellent. When it starts mysteriously appearing inside the house, the fellow decides he's had too much of a good thing and abandons his residence.

I liked that this story turns the "if it seems too good to be true" cliche on its head (there's never anything untoward about the milk; in fact, during the term of the milkman's engagement, life had been significantly better for the drinker). However, it ends abruptly and with insufficient development. It needed another sting for its tail.

Three stars.

Famous First Words, by Harry Harrison

Brilliant scientist devises a contraption to record the genesis of great inventions. It's really just an excuse for a brace of ha-ha vignettes, which aren't very funny.

A disappointment, both given the author and the promising title (which is now useless).

Two stars.

The Biolaser, by Theodore L. Thomas

The Science Springboard is back, this time positing a time when laser scalpels are so thin, they can splice DNA like reel-to-reel tape. Maybe it's possible?

Three stars, I guess.

Those Who Can, Do, by Bob Kurosaka

An impudent college student interrupts his teacher's math lecture with a demonstration of magic. The teacher responds in kind.

No really, that's it.

Two stars.

Wogglebeast, by Edgar Pangborn

Molly, a middle-aged woman with an inherited fancy for magical (if mythical) creatures, befriends a Wogglebeast when it emerges from a pot of chicken soup. She keeps the odd animal, which is never really described until the end, as kind of a pet, kind of a good luck charm. Fortune does seem to follow, and she even, at the age of 41, manages to become pregnant. The story, however, has a sad ending.

A sentimental and well-written tale, it doesn't have much more than emotion going for it. And I'm getting tired of women portrayed solely as mothers or wanting to be mothers.

Three stars.

Love Letter from Mars, by John Ciardi

Good meter on this poem, but after reading it five times, I've still no idea what the author is trying to communicate.

Two stars.

The House the Blakeneys Built, by Avram Davidson

Ugh. Davidson.

Alright. I won't leave it at that. The Blakeneys are the descendants of a four-person crew stranded on a (entirely Earthlike, of course) planet hundreds of years ago. Severe inbreeding has dulled their intelligence and bred in odd superstitions. When a fresh foursome of shipwreckees arive, the results are not happy ones.

Another vaguely promising tale that comes to an unsurprising, uninspiring end.

Two stars.

Four Ghosts in Hamlet, by Fritz Leiber

Finally, we have the longest piece of the mag, about the goings on in a Shakespeare company which culminate in a seemingly spectral conclusion during the Ghost's appearance in Hamlet.

Leiber, of course, recounts from experience, being a prominent actor, himself. But unlike the excellent No Great Magic, there is not a hint of fantasy or science fiction in this F&SF story. And while I appreciated the 30 page, (deliberately) gossipy and meandering behind-the-scenes look at life in an acting company, that's not why I subscribed to this mag.

Three stars.

Back to Reality

What a disappointment that was! If new editor Ferman can't find anyone to write proper SF, or even imaginative F for F&SF, he might as well change the magazine's masthead. As is, it's false advertising.

Oh well. There are plenty of interesting magazines and books next to it on this month's newsstand…

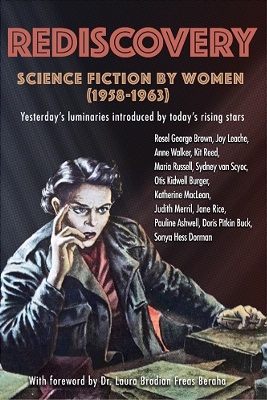

[Holiday season is upon us, and Rediscovery: Science Fiction by Women (1958-1963), on the other hand, contains some of the best science fiction of the Silver Age — many from F&SF's prouder days. And it makes a great present! A gift to friends, yourself…and to the Journey!]

![[December 15, 1964] Failed Flight of Fancy (January 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/641215cover-672x372.jpg)