by Gideon Marcus

Iran's "new" King

This week's foreign news was dominated by affairs in the Middle East. When the papers weren't talking about the United Nations futilely trying to hammer out a peace treaty between Israel and Egypt (whose conflict has become a continuous low burn rather than a short conflagration), they were gushing over the crowing of Persia's "King of Kings".

Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlevi, the uncrowned king of Iran for the last 26 years, chose his 48th birthday to crown himself Light of the Aryans, emperor of "the world's oldest monarchy." Also crowned was his wife, Farah, who became the first empress of Persia since the 7th century A.D.

Taking place in the dazzling Hall of Mirros in Gole-stan Palace, the event was possibly the most expensive coronation in history, with newspaper accounts breathlessly describing the type and number of jewels employed in the various accoutrements of state and decorations. The affair concluded with 101-gun salutes, kicking off a week of celebrations that are just wrapping up today.

According to the Shah, the reason for the long delay between ascension to rule and formalization of said rule was that he did not want to take the grand title until Iran had become a modern, prosperous state.

My only aim is to further the prosperity and glory of my nation, and make Iran the most progressive country in the world, resurrecting its ancient glory and grandeur. For this I will not hesitate to sacrifice my life.

While the newspapers and newsreels seem dazzled by the Shah's extravaganza, many of Iran's 25 million people were less impressed. One young woman, student at the Tehran University, would have fit right in at this spring's protests of the Shah's visit to West Germany:

Why should he spend all this money on his coronation? There are so many poor people. He should give them the money.

It should also be noted that while the Shah did take the throne of Iran in 1941, his reign was not uninterrupted. Unmentioned in all the newspaper accounts I could find of the coronation was the two-year tenure of Mohammed Mosaddeq, the democratically elected but leftist prime minister of Iran from 1951-1953. During the Mosaddeq administration, the Shah fled the country, only returning when a coup removed Mossadeq from power—an event which, if not instigated with assistance from the United States and the United Kingdom, was certainly extremely convenient for both governments.

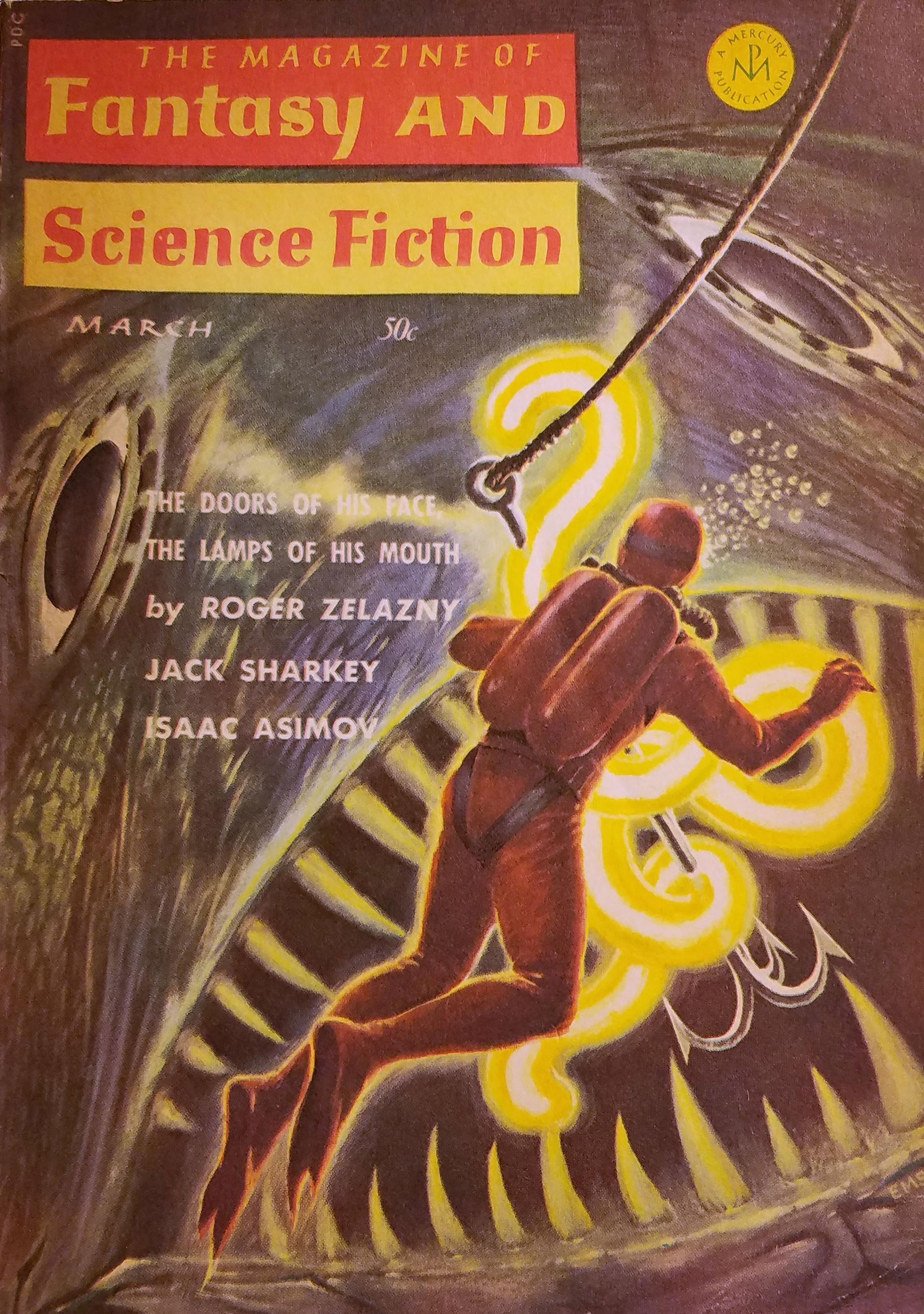

Magazine of Magazines

It has been a couple of years since Analog Science Fiction won the Hugo Award for Best Magazine, but there's no question that it still reigns supreme both in subscribers and general esteem. However, some have complained that editor John Campbell does not do enough to mix up the contents of his publication, relying on the same bunch of authors every month, resulting in a somewhat tired affair.

This month, there are no old hands in the table of contents, but like the throne of Iran, has anything really changed?

by Kelly Freas

by Kelly Freas

What a strange opening novella this is: a long lost colony world is peopled by numerous bands of Scots, operating at an 18th Century technology level…but with an American Indian organization. The latter seems eclectic, using terms like sachem, cacique, as well as counting coup, but no explanation as to why these marooned Celts adopted customs from the western hemisphere are forthcoming.

Anyway, this is the tale of John of the Hawks, a boy on the verge of manhood, who achieves maturity by counting coup on three cattle-rustling men of Clan Thompson. His ascension is delayed by the arrival of men from another world. They represent themselves as scouts, but what they really want is the abundant platinum deposits on planet Caledonia.

The outworlders don't actually play much part in this story. Mostly, we get scenes of John of the Hawks riding horses, battling rival clansmen, facing off against and falling in love with Alice of the Thompsons–a lass who is Every Bit as Good as a Man. It all reads like a dime Western.

And if "Guy McCord" isn't Mack Reynolds, I'll eat my hat. From the interspersed history lessons to the trademark invented slang, it's got his fingerprints all over it.

A low three stars.

Prostho Plus, by Piers Anthony

by Kelly Freas

The writer of the execrable Chthon has thankfully returned to short stories. This is a readable, if not particularly remarkable, tale of a dentist who is tasked with filling the molars of an alien.

A story like this would usually be played for laughs, but Prostho is done straight, with an underlying tinge of horror.

Three stars.

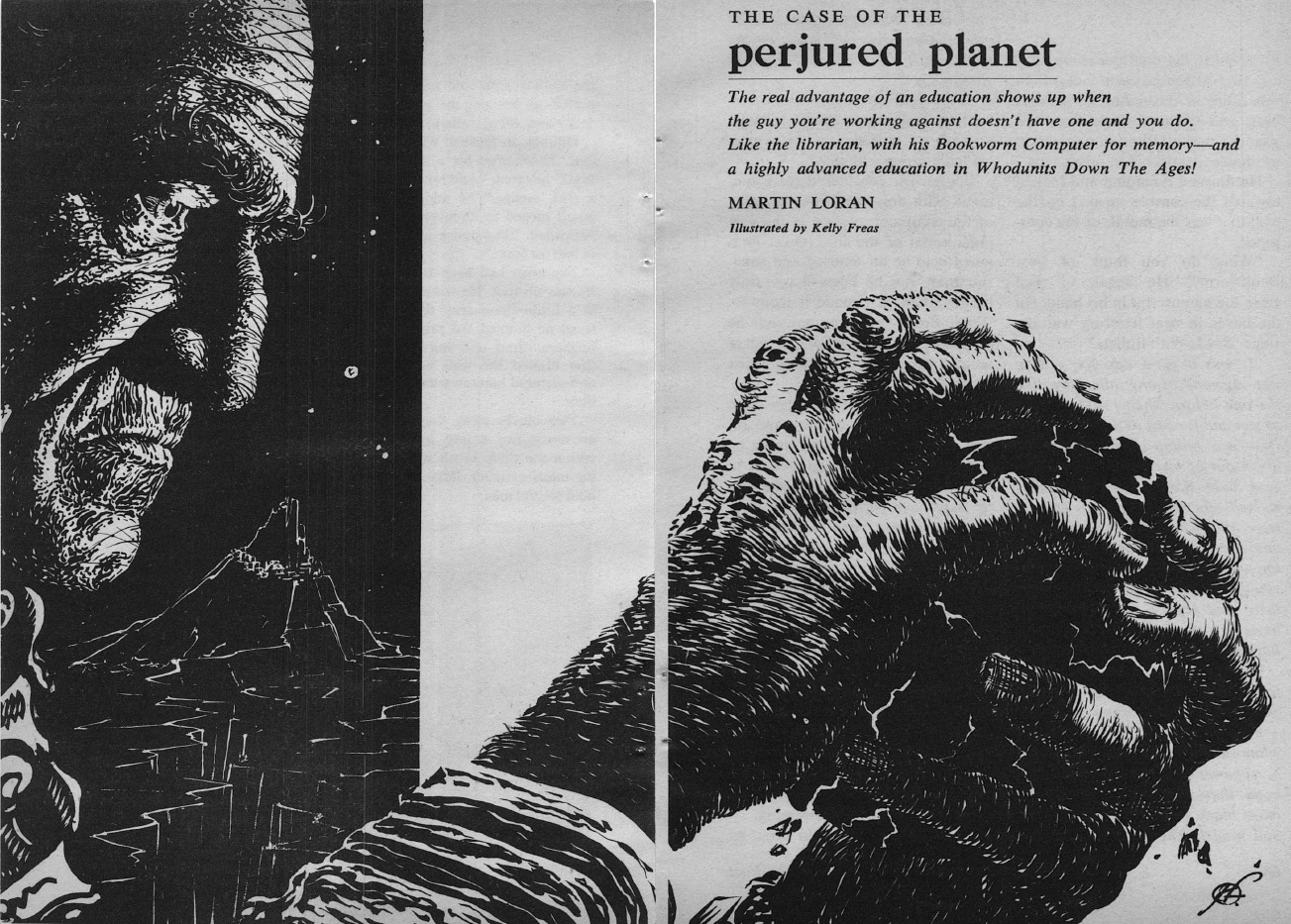

The Case of the Perjured Planet, by Martin Loran

by Kelly Freas

The interstellar librarian, name of Quist, is back for his second story. Using the purveying of books as a cover, the librarian corps is really a division of agents whose job is to monitor the various governments of the galactic confederation.

This time around, Quist is investigating a planet with a secret: it's not that there's evidence that the drab, earthquake-riven world of Napoleon 6 harbors something hidden, but rather the lack thereof. Quist, knee-deep in 20th Century style detective novels, decides to take a page from Sam Spade's book, and opens up a private detective agency on the planet in the hopes that the clues will come to him.

Like last time, it's not a tale that will stick with you, but there's a maturity to the story's telling that suggests Loran is 1) quite a good writer who just needs a better subject/venue or 2) "Loran" is as real a name as "Guy McCord", and a quite good writer is slumming in Campbell's mag.

Three stars.

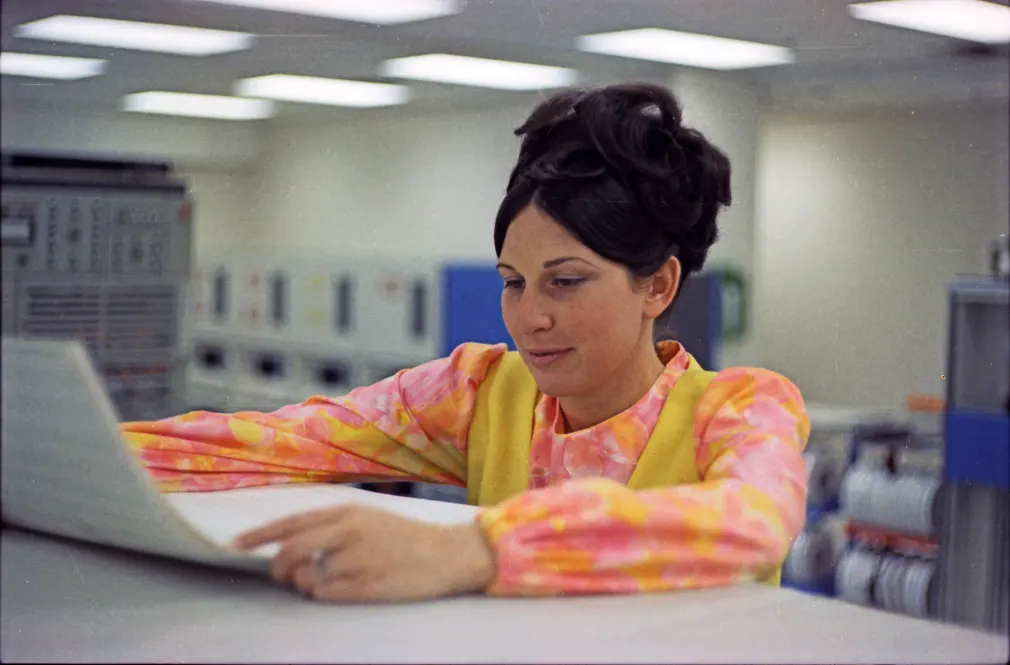

Applied Science Fiction, by Will F. Jenkins

And now for the highlight of the issue. Will Jenkins, better known to the science fiction community as Murray Leinster, is not only a renowned writer–he also is an inventor. Here is the tale of how he conceived the incredibly useful technology of front projection, allowing actors to appear in ready-made projected scenery in a far more convincing and versatile manner than rear projection.

I really enjoyed this piece, and bravo Mr. Jenkins. Five stars.

The Cure-All Merchant, by Jack Wodhams

by Kelly Freas

A doctor manages a successful practice by dealing in placebos, much to the horror of the straight man inspector assigned to investigate his activities. This piece goes on endlessly, asserting that drugs are useless, and the human mind is all.

Ducks like a quack. One star.

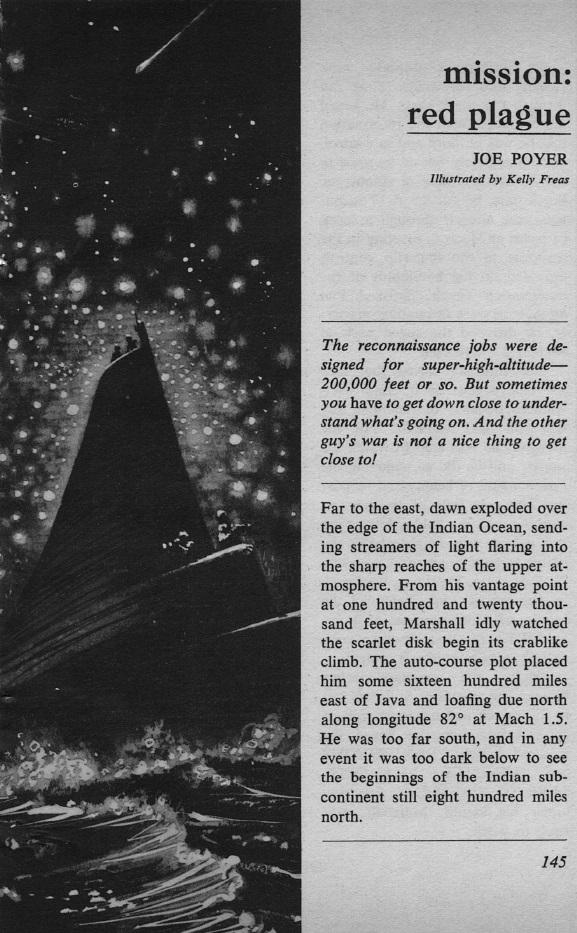

Mission: Red Plague, by Joe Poyer

by Kelly Freas

This last piece is a sort of sequel to Operation: Red Clash, again involving the mythical X-17 hypersonic reconaissance plane. This time, the spy jet observes the deployment of a biological plague on the Sino-Soviet front. The problem is the X-17 cockpit isn't completely airtight…

Poyer writes competent Caidenesque technophiliac stuff, but he has trouble hanging an interesting story on it.

Another low three stars.

Spot the difference?

On the surface, it appears Analog has gotten out of its rut, exploring the output of several new authors. But it doesn't take much inspection to see that Campbell's mag offers more of the same, between the pseudo-Reynolds piece, the workmanlike Loran, Anthony and Poyer, and the truly bad (but Campbell-pleasing) Wodhams. Only the Jenkins/Leinster is truly noteworthy, pulling the issue up to a three star rating.

That puts it below Fantasy & Science Fiction (3.25) and New Worlds (3.2) and above IF (2.8) and Fantastic (2.7) In other words, middlin', which one would expect of a mag doing the same ol', same ol'.

For those keeping up with statistics, the amount of superlative stuff this month could fill a Galaxy-sized mag; not terrific given that five magazines came out with a November 1967 cover date. Women produced a surprising 12.5% of all new short fiction, an achievement rendered less impressive for those stories all appearing in one magazine–F&SF, which was the best magazine of the month.

So here's hoping Analog goes for real change next month rather than the veneer of change. Maybe it'll be a failed experiment…or maybe Campbell will get to oversee a new Golden Age. Be bold, John!

![[October 31, 1967] Same ol' (November 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671031cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 16, 1965] Return to a Quagmire (March 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/650214cover-672x372.jpg)