by Gideon Marcus

Out and in

Being something of a geography buff, one of my favorite games is to go to a thrift shop and inspect their globe collection. I can generally tell what year a globe was manufactured from the configuration of countries. And while we haven't had anything like the banner year of 1960, when more than a dozen African states sprang into existence, nevertheless, there are still enough changes every year to keep the game going.

For instance, this month, the Kingdom of Swaziland with its 400,000 denizens, achieved independence from the United Kingdom. The second-smallest African country, is not entirely free, of couse. It is completely surrounded by South Africa, with all transportation lines running through Pretoria. The money is South African. All telegraph lines go through South Africa. As for their economy, it's mostly propped up by British hand-outs.

But they do have sovereignty, something South Africa tried to snatch from them time and again, but which was thwarted by the British. Plus, the new country has vast mineral reserves of asbestos and iron, plus forests and fertile soil. So King Sobhuza I just might make a go of things.

Going the other way, the people of West Irian (formerly Netherlands New Guinea) have has been annexed as Indonesia's 26th province. Six years ago, the United Nations stepped in to stop a budding conflict between the Dutch and the Indonesians, who both laid claim to the region. Now the 800,000 poverty-stricken inhabitants are officially under the auspices of General Suharto. Sometime soon, they will be given the choice between independence and a union with their neighboring would-be superpower. It is anyone's guess how free and honest the local elections can be under the Suharto dictatorship (i.e. don't expect a free West Papua any time soon…)

The Morning Star Flag—which you won't see flown until and unless the Irians get independence…

Good and bad

Speaking of mixed bags, this month's Fantasy and Science Fiction has much to recommend it, but then there's all the rest of the magazine. See for yourself:

by Ronald Walotsky

The Meddler, by Larry Niven

Bruce Cheeseborough, Jr. is a private dick operating some time in the near future. While in the course of waging a one man crusade against the new crime boss, Lester Dunhaven Sinclair, a certain meddler crosses his path. Said meddler first appears as a nebbishy, softish man, but he quickly betrays himself as a protean blob, possessed of all manner of wondrous powers. The "Martian" offers to help the detective, granting him invulnerability, the gift of flight, time dilation…but Cheeseborough finds the tilting of the scales unsporting.

Still, when the detective makes his final assault on Chez Sinc, it's going to take every resource he has, from human wit to alien marvel, to come out the other end alive…

The Meddler is a brilliant piece of genre hybridization, combining hard-boiled noir with cunning science fiction. Every piece of the story's myriad puzzles is meticulously laid out, so that an astute reader can figure out the revelations just before they materialized. Beyond that, the piece is funny as well as perfectly paced.

Five stars, and a nice broadening of the author's talents.

Time Was, by Phyllis Murphy

Picture a man so obsessed with saving time, that he applies the art of speed reading to life. You know: skipping over most of it, trying to absorb only the salient points. Except, how do you know which bits are the important ones? And what if you lose the ability to focus on any given thing in the pursuit of apprehending everything?

This story reminded me of a friend who insisted a person must do several things at once to be truly efficient. If she read the paper, she listened to the radio. When we watched television together, she'd inevitably crochet. Remarkably efficient…except half the time, she lost track of the show's plot and had to ask us what was going on.

Three stars.

The Wide World of Sports , by Harvey Jacobs

They say that football is a bloody sport, but it's nowhere near as bloody as whatever Jacobs is describing in this story, featuring machine guns, the slaughter of all audience members of a certain name, and general mayhem.

This story would be more effective if it made a lick of sense and/or had a plot. Two stars.

by Gahan Wilson

Coffee Break, by D. F. Jones

There's a Laugh-In bit where the projected news break underneath the action runs, "The United Nations today voted unanimously on everything; UN police are still looking for who put grass in the vents."

This story covers the exact same ground, but it takes much longer to do it, and not in nearly as funny a manner.

Two stars.

Dance Music for a Gone Planet, by Sonya Dorman

Fiddling after Rome is burnt? A tinge of hope for a post-apocalyptic ode?

I'm not sure—I found this one a bit too obtuse to understand. Maybe I'm the obtuse one.

Two stars.

Possible, That's All!, by Arthur C. Clarke

The Other Good Doctor takes umbrage at Asimov's assertion that nothing can go faster than light. He offers up some counterexamples, but they're honestly rather feeble, and the article is not particularly coherent.

Three stars.

Try a Dull Knife, by Harlan Ellison

Eddie Burma is an empath, life of the party, and he has so much to give. Folks are drawn to his magnetic personality like moths to flame, but, unknowingly, each takes a little bit from Burma in each encounter. This is the price of popularity: eventually, there can be nothing left of you, the you behind the glamor and charm, because no one wants you. They just want what rubs off.

If you've heard this refrain before, it's because Ellison delivered a soliloquy on the subject in his last collection, From the Land of Fear. Harlan is afeared that no one really loves him; they just love The Talent that resides within his physical husk. Readers of that collection also have encountered Knife in its embryonic form, a snippet of it among the story fragments at the beginning of the book.

Anyway, I've said it before and I'll say it again: if your soul overlaps with Harlan's, then his writing resonates with you as The Truth. If you are much unlike the man (as, for instance, I am), then you can admire the way he strings words together, but they don't move much.

Three stars for me. Four stars, perhaps, for you.

Segregationist, by Isaac Asimov

Organ transplants are the topic du jour in both science and science fiction. I find it particularly interesting that much is made of the muddled identity of a person when they incorporate the parts of other humans (viz. Van Scyoc's A Trip to Cleveland General in this month's Galaxy). This time around, Asimov takes things a step further: are humans less human if they have metal hearts? And are robots more human if they incorporate biological components?

I liked this story, one of the better pieces Dr. A has done since largely going on fiction hiatus after the launch of Sputnik.

Four stars.

The Ghost Patrol, by Ron Goulart

Speaking of crossed genres, Ghost Patrol is the latest in the Max Kearny series about an art director who solves occult crimes in his spare time. These yarns range from hilariously clever to limp.

This one, about a free doctor beset both by celebrity ghosts and Bircher anti-freeloaders, belongs, sadly, in the latter category.

Two stars.

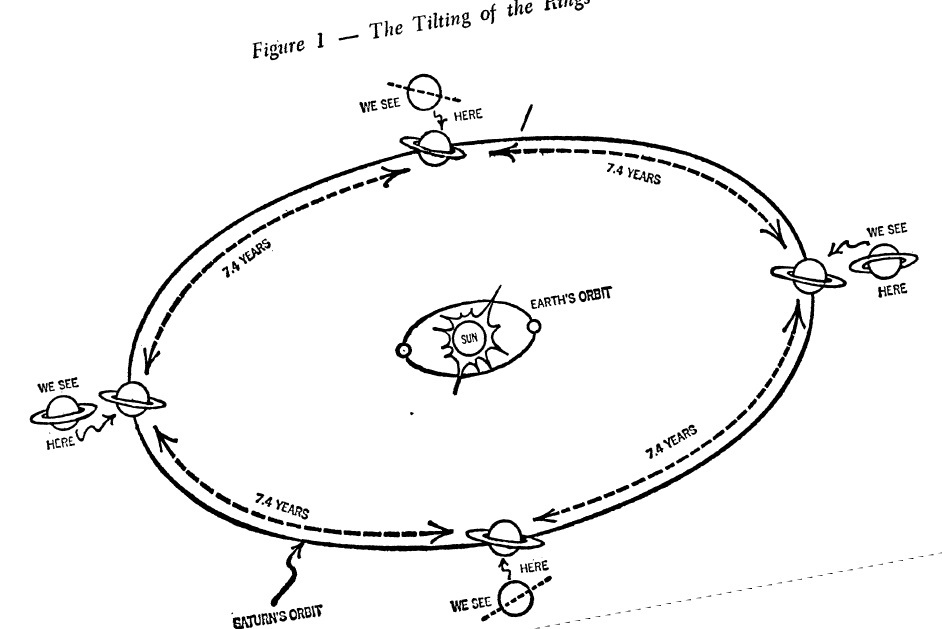

Little Found Satellite, by Isaac Asimov

This month's piece is worth it for the funny anecdote that forms its preface. The rest is a pleasant, if not particularly deep, history of Saturn's telescopic observation. The piece culminates in the discovery of Saturn's tenth moon, Janus, just outside the ring system.

Four stars.

The Fangs of the Trees, by Robert Silverberg

At a recent convention, my daughter led a panel entitled "Plants vs. People", in which the panelists and audience discussed green menaces of various kinds. Triffids, killer ragweed, stuff like that. I wish I'd had Fangs as an example, as it's a good one.

Zen Holbrook is runs a plantation on a world countless light years from Earth. His trees produce a valuable, hallucinogenic-juiced fruit. They're also quasi-sentient, something like ultra-advanced Venus Fly Traps. Though he tries to keep his relationship with his trees strictly business, he can't help ascribing them personalities, giving them names, and treating them like pampered pets.

Which makes it all the more difficult when he gets news that all of the trees in Sector C have been afflicted with "rust", a disease that not only spells their impending death, but has the risk of spreading throughout the whole planet. Holbrook must kill his friends lest an entire world's economy die. Further complicating the matter is his 15-year old niece, Naomi, who would rather die than see the grove decimated.

It is implied, though never specifically stated, that there is no less destructive way to solve the problem: not only must the trees die, but so must an entire species of benign hopper-bear—a link in the infection cycle. Lord knows what that will do the local ecosystem, but "the needs of the many…"

It's an interesting, thought-provoking piece, composed with Silverberg's usual excellence, though I'm not quite sure which side we're supposed to take, if any. Like, do we all need to grow up and realize that ecological destruction is a valid and important necessity? Or is Zen actually the villain? I could have done without so much of the Uncle's attraction for his niece, too, even if it was supposed to say…something…about Zen's character. I know that the word for people who ascribe the emotions of an author's creation to the author himself is "moron" (at least, per Larry Niven), but Silverbob sure includes a lot of just-pubescent minors in his stories…

Four stars.

Whaddaya make of that?

If you read judiciously, this month's mag is terrific, kind of like how, if you parse the news in just the right way, it's all positive developments. Look deeper, and the seams show. Still, whether the news or the magazine are half full or empty all depends on your temperament, I suppose.

I guess I'll leave with the wishy washy conclusion that's always true: things could be worse!

![[September 20, 1968] It comes and goes (October 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/680920cover-651x372.jpg)