Please enjoy this duet of stories by a pair of veterans (both the authors and the reviewers!)

by Cora Buhlert

The Escape Orbit by James White

When I spotted The Escape Orbit by James White in the spinner rack at my local import store, what first attracted me was the cover, showing two humans fighting a tusked and tentacled monstrosity. But what made me pick up the book was the tagline "Marooned on a Prison Planet". Because stories about space prisons are like catnip to me.

Though the space prison in The Escape Orbit is rather unconventional, housing human prisoners-of-war in the sixty-one year war with an alien race called "Bugs", because nobody can pronounce their real name.

At the beginning of the novel, the surviving officers of the battlecruiser Victorious ("erroneously named," the narrator Warren muses) are taken prisoner and dumped on what they assume is an uninhabited world. They are proven wrong, when one Lieutenant Kelso appears. Kelso informs the newcomers that the Bugs have dropped off half a million human prisoners-of-war on the planet with only scant supplies. Escape is supposed to be impossible. If the humans manage to flee anyway, there is a guardship in orbit. Kelso also insists that the newcomers are in danger.

It turns out that the human prisoners on the planet are divided into two groups. The Escape Committee, led by Kelso, who focus all their efforts on escaping, and the Civilians, led by one Fleet Commander Peters, who have resigned themselves to their fate and set up villages. The Civilians and the Committee are hostile towards each other and on the verge of fighting. The newcomers are expected to side with one group. But before making a decision, Warren wants to listen to both sides. And since he was Sector Marshall before he was captured, that makes him the highest ranking officer on the planet.

Warren and psychologist Ruth Fielding realise that the situation on the prison planet is volatile. The Committee is losing members, so those who remain become ever more fanatical. Ruth points out that the Committee are chauvinists, because most female prisoners join the Civilians and then seduce Committee members. Warren fears that as the Committee becomes more fanatical, they may try to take over the planet and cause a civil war. To prevent this, Warren decides to use his position to keep things calm. He joins the Escape Committee as a counterweight to Fleet Commander Peters and the Civilians.

The Great Escape… in Space

Warren takes over the Committee, learns about the escape plan and schedules the escape for three years in the future. He starts a good will initiative towards the Civilians to persuade them to help. Warren also tries to squash the not so latent male-centered prejudice among the Committee and appoints Ruth Fielding to his staff.

Warren may be no chauvinist, but he doesn't know much about women and people in general. And so he is surprised that the Civilians are forming families and having children. At this point, one suspects Warren needs a crash course in human biology. Furthermore, Warren also manages to bungle the chance at a relationship with Ruth Fielding – twice.

Once Warren succeeds in winning many Civilians over, the bulk of the novel focusses on the preparations for the escape. However, Warren also furthers the progress of technology, improves the communication network as well as the distribution and preservation of knowledge and even organises the colonisation of another continent.

As the escape draws closer, tensions erupt both between Civilians and Committee members as well as within the Committee itself. Things come to a head when a new group of prisoners arrives a few days before the escape. Hubbard, one of the new prisoners, reports that the war is over, because humans and Bugs have managed to battle each other to a standstill and both civilisations are falling apart. Even if the escape succeeds, it will be futile, because there is no military to return to.

Warren imprisons Hubbard and goes ahead with the escape anyway. The attempt succeeds and Committee commandos manage to hijack both the enemy shuttle and the guardship. The surviving Bugs are taken prisoner and sent to the planet, while their ship is crewed by the most loyal Committee members.

Warren returns to the planet once more to explain his true plan. For he had realised even before the arrival of Hubbard that the human military would collapse and that there was little hope of rescue. Warren also realised the prison planet was on the verge of civil war and would regress to savagery within a few generations.

By giving everybody a shared purpose, Warren managed to smooth over the tensions, preserve knowledge and create a stable society. Furthermore, he also used the escape to separate potentially violent Committee members from the general population. Warren announces that he will take off with the Committee members deemed unsuited to peaceful life and leave the rest of the former prisoners behind to rebuild civilisation. He also admonishes them to communicate and cooperate with the Bug prisoners, so future wars can be avoided.

I'm usually pretty good at gauging where novels are headed, but The Escape Orbit surprised me. Initially, the book seemed like a science fiction version of the WWII prisoner-of-war escape tales that have proliferated in both the German and English speaking world in recent years. The best known English language example is The Great Escape by Paul Brickhill from 1950, which was turned into a Hollywood movie two years ago. Meanwhile, in West Germany there is a flood of POW novels such as So weit die Füße tragen (As far as the feet will go, 1955) by J.M. Bauer or Der Arzt von Stalingrad (The Doctor of Stalingrad, 1956) by Heinz G. Konsalik, who specialises in such tales and also penned Strafbataillon 999 (Penal battalion 999, 1959), where the twist is that prisoners and guards are nominally on the same side. All of these novels were huge bestsellers and turned into successful movies and TV series.

In The Great Escape and the various West German novels, escaping from the terrible conditions of a POW camp is a matter of survival. However, the conditions on the prison planet in The Escape Orbit are far from terrible. And so I quickly sided with the Civilians and wondered why Warren and the Committee were so eager to escape, when they were better off on the planet than wasting their lives in what was clearly a pointless war. For a time, I even had the sinking feeling that I had accidentally purchased a military science fiction novel akin to Robert A. Heinlein's 1959 Starship Troopers, which I disliked immensely, once I realised I was not in fact reading about a dystopia, but about a society the author considered admirable.

But White tricked me, for Warren was on the side of the Civilians all along and the escape plan was a way to occupy the Committee fanatics and keep them from interfering with the establishment of a peaceful society. Of course, military (science) fiction can be both pro- and anti-war. The Escape Orbit comes down firmly on the anti-war side. I was surprised to see a high ranking officer like Warren portrayed sympathetically, because in West German postwar literature and film, any officer with a rank higher than captain is usually portrayed as a blustering idiot or bloodthirsty warmonger, probably inspired by real world experiences with both types during WWII.

I knew nothing about James White before picking up this novel. Turns out White is a long-time science fiction fan and author best known for his Sector General stories about a hospital space station. White hails from Belfast (Andersontown, the city in the novel, is named after the suburb where he lives) in Northern Ireland, where religious tensions run high. Thus, White knows how easily hostilities between opposing groups can escalate into violence.

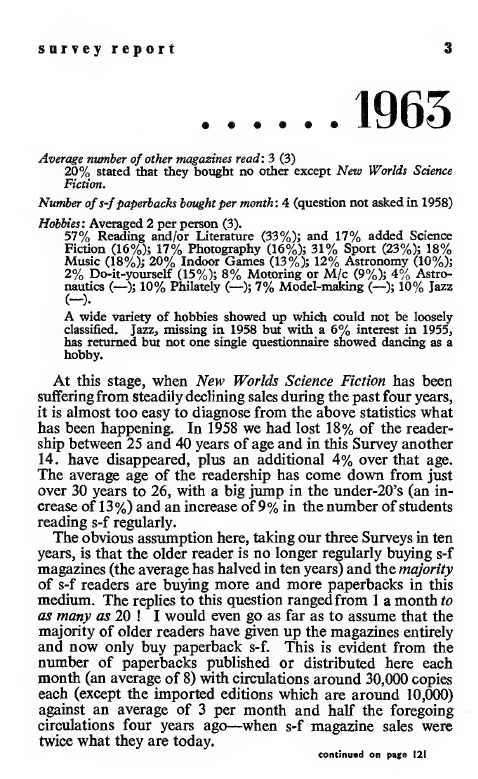

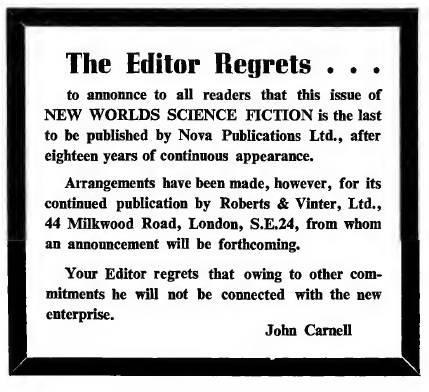

The Escape Orbit is not quite as brand-new as I assumed, since the novel was serialised, almost identically, as Open Prison (a more appropriate title in my opinion) in New Worlds last year, reviewed by our own Mark Yon.

The Escape Orbit is very much an anti-Analog novel, where humans are not superior to the aliens, where war is pointless and cooperation, both between humans and aliens and opposing groups of humans, is preferable to fighting. This is certainly a message for our times, as the spectre of war raises its ugly face again in South East Asia.

Four stars

Space Opera by Jack Vance

By Rosemary Benton

Jack Vance is a gifted writer who has received a lot of attention in the last year. He has rightfully been awarded praise for his world building in Ace Double F-265 and "The Star King", but thus far has proven to be somewhat inconsistent in the pacing of his stories. This is not to say that he hasn't been rapidly improving his writing. At times his storytelling has been spot on, such as in "The Kragen".

Thankfully, with "Space Opera" he does not fall short in either department. The pacing and world building are both excellent, but with Vance's latest release there still remain issues that prevent his works from rising beyond "entertaining", or even "ambitious". He has yet to become "timeless", but by God does he come close sometimes.

"Space Opera" is Vance's newest novel. In it he tells the story of humanity's pride, and how fragile it is. In the far future, Earth's high society is still very much preoccupied with its perceived perfection of music as an art form and humanity's generally superior understanding of music as a universal concept. Dame Isabel, a patron of the operatic arts, takes it upon herself to honor a promise made to a troupe of visiting musicians from the elusive planet Rlaru. As they sent a troupe to visit Earth, so will she bring some of Earth's finest music to their planet. In preparation for this she gathers an exclusive selection of singers and musicians, she brings the world's foremost musicologist aboard the good ship Phoebus, and sets off to Rlaru with missionary zeal. On the way they will of course stop to educate other alien races on the magnificence of Earth's musical accomplishments. The success of the undertaking is… complicated.

What Makes Something High Art?

Our cast of protagonists begin their journey with a very well defined and well researched mindset. The first few chapters of "Space Opera" are lousy with musical terms, phrases and theories that are absolutely esoteric for general audiences. Intentionally, Vance is setting up a practically aristocratic 19th century approach to how culture should be defined: if a culture's art is too accessible, then it's not sophisticated. If it's not sophisticated, then it's inferior.

Exclusivity is a prime ingredient to make a culture great in their eyes. Exclusivity of musical theory, exclusivity of musical venues, exclusivity of the language of music (in this case favoritism of German and French language operas on Dame Isabel's expedition), everything about an advanced musical sensibility in a culture should speak to exclusivity. Which of course also translates to the most desirable audience being comprised solely of wealthy patrons. The favored company of Dame Isabel is academic specialists, and the audiences she most voraciously seeks at each stop along her tour are the alien societies' elite.

The best parts of Vance's story are when these very human expectations are subverted. On Sirius the company is unable to make sufficient adjustments for the cultural norms of the native population and the performance fails spectacularly. On Zade they are vetted by a native music critic who mirror's Earth's own narrow minded music specialists. He judges the performance of Dame Isabel's troupe by applying his own culture's standards against Earth's operas, and finding them deficient dismisses them and then asks for monetary compensation for his time. On Skylark the troupe finds that just because the people planet-side express appreciation for operatic craft does not mean that such appreciation is meant truthfully – it turns out that their attempts to keep Dame Isabel's people on for more performances is just so that the convict population can begin switching out the crew's musicians for physically altered convicts with comparable musical proficiency.

Music's Greatest Power

The emotional resonances of music are the pinnacle of Vance's exploration of music's power. On Yan, Earth's operas are interpreted to represent that which has been lost by the planet's people. The response is one of violence from the spectral remnants of the native population. On fabled Rlaru, Earth's operas are too dry for the natives to become interested in. Their culture already achieved the highest levels of artistic perfection, so seeing another people's comparatively primitive attempt at high art is boring and uninspired. However, a passionate performance held in back of the ship by a ragtag, informal group of the performers draws a massive, appreciative crowd.

"Space Opera" is a novel of massive potential, but Vance tries to compress the issue of human beings' cultural superiority complex in too short a time. The setup is exceptional. We know exactly where Dame Isabel, Roger Wool, and Bernard Bickel are coming from in terms of background, personality, and motivation. They go through a harrowing ordeal in the process of reaching Rlaru, and their time on Rlaru is extremely memorable. The fall of the plot is that there is not sufficient time given for the characters to reflect on their experiences. Because of this "Space Opera" ultimately falls short on its final satirical delivery.

Dame Isabel, the character whom I would argue is the central protagonist of the story, concludes her expedition to spread Earth's "highest" cultural medium by returning to Earth and holding a brief press conference reflecting on her and the crew's experiences. She starts the story as an elitist and remains one by the end of the novella. Roger Wool, her bumbling nephew, returns to Earth with his on-again, off-again fiance Madoc Roswyn, and some vague promise of a forthcoming book about the Phoebus' adventure. He begins as the naive, clueless, kept relative of Dame Isabel, and concludes the story as such.

The one character who has the largest arc was Bernard Bickel, Earth's premier musicologist. Despite being relegated to the role of a world building tool and Dame Isabel's consultant, his dialogue in the last few pages at least hints at growth. At the press conference mentioned earlier he comments in a round about way that the expedition gave him an appreciation for the varied reactions Earth's music got on the different planets they visited. But the story's detachment to his experiences relegates any development of his character, and more importantly what he represents, to the background.

At the best he seems like an anthropologist accompanying an invading fleet. Along the way he watches the Earth musical missionaries meet disaster after disaster on their blind quest to prove humanity's superior grasp of music. At worst he could be seen as a character who should have been the primary protagonist, but was swept under the ornate, oriental rug of Dame Isabel's sponsorship and her nephew's charming fumbling.

The Curtain Call

"Space Opera"'s concept would make a great full length novel. But as nearly a novella, it's just doesn't go deep enough. I thoroughly believe that Vance has something really special here, but unless he expands the story in the future it's a piece that will fade into the background of science fiction in time. Perhaps Vance will come to see "Space Opera" as a practice piece for writing satire, but as it stands right now it's merely a three star story.

![[February 4, 1965] Space Prison of Opera (February Galactoscope #1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/650206covers-672x372.jpg)

![[March 27, 1964] The End of an Era? Not With a Bang…. ( <i>New Worlds, April 1964</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640327cover-409x372.jpg)

![[February 27, 1964] Beatles, Boredom and Ballard ( <i>New Worlds, March 1964</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640227cover-649x372.jpg)

![[January 28, 1964] Beatles, Prisons and Doctors ( <i>New Worlds</i>, February 1964)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640128cover-652x372.jpg)