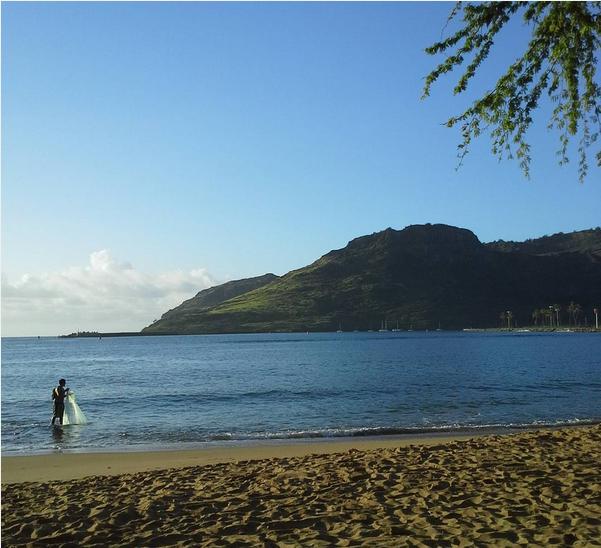

Greetings from sunny Kaua'i! It seems like only yesterday I was reporting from this island's idyllic shores. Much has changed, of course–Hawai'i is now a state! 50 is a nice round number, so perhaps we won't see any new entries into the Union for a while.

Accompanying me on this trip is the last science fiction digest of the month, the Fantasy and Science Fiction. On a lark, I decided to read from the end, first. In retrospect, I'm glad I did, but it certainly made the magazine a challenge. You see, the stories at the end are just wretched. But if you skip them (or survive them, as I did), the rest of the magazine is quite excellent.

Let's get the drek over with straight-away, shall we?

Some unknown named C. Brian Kelly offers up the disgusting and sadistic The Tunnel, three pages about a vengeful cockroach that you need never read. 1 star.

Meanwhile, the normally excellent Robert F. Young offers the strangely prudish Storm over Sodom, which somehow rubbed me the wrong way all the way through. 2 stars.

Whew. Now let's go to the beginning and pretend the last 20 pages never happened.

Brian Aldiss, who wrote the variable fix-up Galaxies like grains of sand is back with what I hope is the first in a series of tales about life on Earth in the very distant future. Hothouse portrays a hot, steamy world dominated by vegetable life. Indeed, a single banyan tree has become a global forest, and within it reside a myriad of mobile plant creatures that comprise almost all of the planet's species. Humanity is a savage race, clearly on the decline. Their only hope, perhaps, will come from the outer space they once called their own domain.

It's a beautifully crafted world, the characters are vivid, and if the science stretches credulity, it does not entirely break it. Five stars

Time was is a pleasant piece by Ron Goulart involving a homesick young woman, the trap that tries to lure her back to the 1939 of her childhood, and the dilettante detective of occult matters who tries to save her. Four stars.

I've said before that Rosel George Brown is a rising star, and Of all possible worlds is my favorite story of hers yet. A beautiful tale of an interstellar explorer and the almost-humans he meets on a placid, emerald-sand beach. They seem to be primitives, but sometimes the end result of scientific progress is a pleasant, contemplative rest. Anthropology, biology, love, and loss. Five stars.

Marcel Ayme is back with his The Ubiquitous Wife, about a young woman who can multiply herself infinitely and thus live a thousand lives at once. Like his other stories, it is droll and engaging. The translator did a good job of conveying Ayme's clever turns of phrase. Three stars.

Theodore L. Thomas provides The Intruder, a subtle time travel story featuring a backpacker fishing trilobites at the dawn of the Devonian era. In a nice touch, it turns out he is not the intruder; rather it is the little blot of algae that threatens to inevitably populate the fisher's pristine, lifeless world. Four stars.

Finally, we have Isaac Asimov's non-fiction article, Order, Order!, on the subject of entropy (the amount of energy unavailable for work; or the amount of disorder in the universe). It's a topic that everyone knows something about, but few have a real handle on. The Good Doctor does an excellent job of explaining this esoteric matter. Four stars.

What a pity–if not for the two lodestones at the end of the issue, this would be a rate 4-star magazine. Still, even with them, the score is a comfortable 3.5 stars, which makes F&SF the best digest of the month. It also has the best story of the month: Hothouse. Finally, it features fully 50% of the month's woman authors; sadly, there are just two.

See you on February Oneth–if NASA's hopes are fulfilled, I will have an exciting Mercury Redstone mission to talk about!