by Gideon Marcus

An alien cataloging our solar system for an Encyclopedia Galactica might summarize our home in this brief sentence:

"Solitary yellow dwarf, unremarkable, with a single planet of note; also, a few objects of orbiting debris."

That may strike you as an affront given the attachment you have to one of those pieces of debris (the Earth), but from a big-picture perspective, it's quite accurate. Of all the masses whirling around the sun, the planet Jupiter is by far the biggest. It is, quite simply, the King of Planets.

As we stand on the precipice of planetary exploration, it is a good time to summarize what we know about this giant world, especially in light of recent discoveries made by ground telescopes. Thus, here is the fourth in my series on the planets: Jupiter.

Let's start with the name. Why did the ancient Romans choose to identify Jupiter with the King of Gods? Certainly not based on its mass – how could they know that? Jupiter is, however, one of the brightest objects in the sky. It also is visible more often than the slightly brighter Venus. Because it so dominates the night, it is not surprising that it got an imposing name.

For thousands of years, very little was known about Jupiter beyond its brightness and its motion among the stars – the latter being what flagged it as something that wasn't a star. Then, around 1600, a fellow named Galileo built himself a telescope and aimed it at the planet.

What a surprise that was! Suddenly, this bright point of light was a disc. More than that, it was blemished: alternating bands of light and dark defaced its face. The biggest surprise? An indisputable quartet of smaller bodies orbited the planet. This was solid evidence that Earth was not the center of the universe. So shocking was this discovery that it shook the very foundations of the Catholic Church, and Galileo's findings were suppressed.

Luckily for us, Rome was not the center of the universe, either. The last three and a half centuries have seen hundreds of astronomers turning their 'scopes eagerly at the King of Planets, scribbling down their discoveries. Here are a few:

Based on the motion of Jupiter's moons, we know its mass to be about 320 times that of the Earth.

Jupiter seems to be made mostly of hydrogen, like the sun, but without the size needed to fuse the stuff, like a star.

There is a giant red spot on Jupiter that has been in existence at least since we started looking at the planet. It appears to rotate, and not in a uniform manner. It is probably some kind of atmospheric phenomenon.

The planet seems to have a day of about 10 days (based on the movement of what appear to be its clouds).

Jupiter has an axial tilt of just 3 degrees. It essentially has no seasons in its twelve year trek around the sun.

Measuring the timing of the eclipses caused by the four "Galileian Moons" led to the first determinations of the speed of light.

Eight moons beyond those found by Galileo orbit the planet, though none of them are as big. The latest was found just a decade ago, in 1951.

There are stable points one sixth of the way ahead and behind Jupiter in its orbit (actually, such points of stability exist with all planets as part of their gravitational dance with the sun, but Jupiter's are the most pronounced as it is the biggest planet). Inhabiting these points are swarms of asteroids that drifted in there over time and were trapped. These bodies are named after heroes of the Trojan War, one point bearing Greeks and the other, Trojans. As a result, these areas of gravitational stability are called the "Trojan Points."

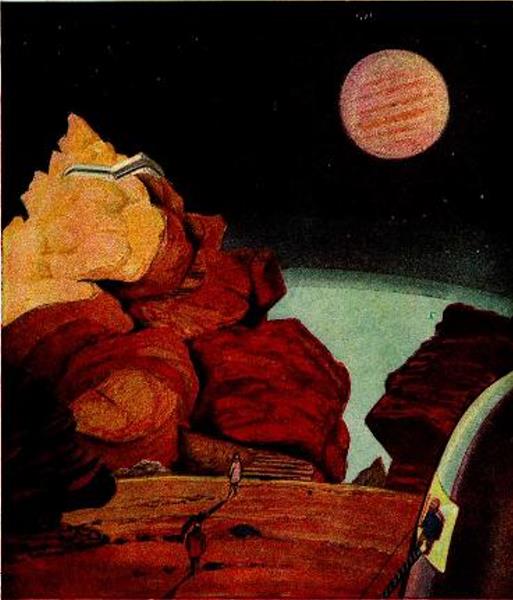

We still do not know if Jupiter has a solid surface. Are there oceans of methane or ammonia floating around inside that huge volume, enough to swallow 1300 Earths? Or does the hydrogen simply get denser and denser until it becomes liquid? Is there a dense core in the middle?

Until we are able to send probes to Jupiter (and scientists are just starting to dream up missions involving the new, giant Saturn rocket), many of the planet's mysteries will remain unsolved. But not all of them…

In the last ten years or so, a brand new way of looking at Jupiter has been developed. Light comes in a wide range of wavelengths, only a very small spectrum of which can be detected by the human eye. Radio waves are actually a form of light, just with wavelengths much longer than we can see. Not only can radio be used to communicate over long distances, but sensitive receivers can tell a lot about the universe. It turns out all sorts of celestial objects emit radio waves.

Jupiter is one of those sources. After this discovery, in 1955, astronomers began tracking the planet's sporadic clicks and hisses. It is a hard target because of all of the local interference, from the sun, our ionosphere, and man-made radio sources. Still, scientists have managed to learn that Jupiter has an ionosphere, too, as well as a strong magnetic field with broad "Van Allen Belts." It also appears to be the only planet that broadcasts on the radio band.

Using radio, we will be able to learn much about King Jove long before the first spacecraft probes it (perhaps by 1970 or so). It's always good to remember that Space Age research can be done from home as well as in the black beyond. While I am as guilty as the next fellow of focusing on satellite spectaculars, the bulk of astronomy is done with sounding rockets and ground-based telescopes – not to mention the inglorious drudgery of calculations and report-writing, universal to every science.

So just you wait, Jupiter. By hook or by crook, we'll soon figure out what makes you tick. And click. And hiss.