It's going to be a dreary month, if October's selection of digests is any indication.

Of course, my mood isn't buoyed by the fact that I must compose this article in long-hand. I hate writing (as opposed to typing; and typing on an electric is sheer bliss). On the other hand, I'm the one who chose to occupy much of the next few days in travel, and fellow airplane passengers don't appreciate the bang bang of fingers hitting keys.

I'm getting ahead of myself. Let's start at the beginning, shall we? As I write, I am enjoying my annual plane trip to Seattle for the purpose of visiting my wife's sister, myriad local friends, and to attend a small but lively science fiction convention. This one is singular in that its attendees are primarily female, and its focus is woman creators. People like Katherine MacLean, Judith Merril, Pauline Ashwell, Anne McCaffrey, etc.

Once again, I get to ride in the speedy marvel that is the jet-powered Boeing 707. San Diego to Seattle in just a few hours is a luxury to which I hope I never become jaded. Although I will concede that the roar of jets is less pleasant a sound than the thrum of propellers.

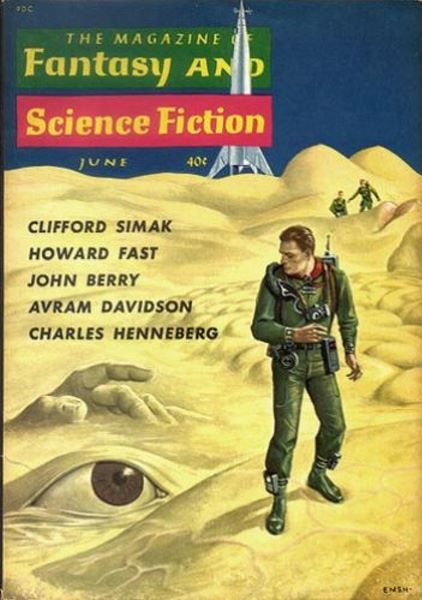

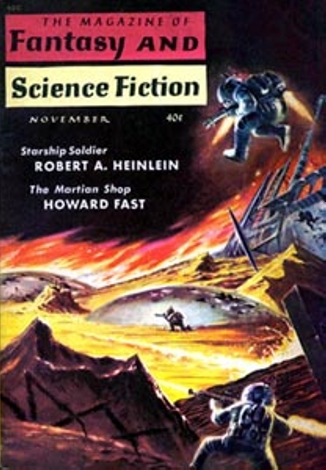

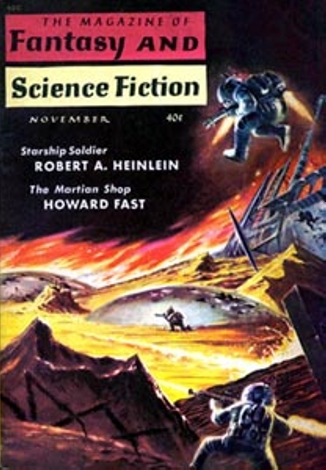

I made several attempts to read this month's Astounding, but I could find nothing in it I enjoyed. I'll summarize that effort later. In the meantime, I have just finished the November 1959 F&SF, and if you can read my chicken-scratch (I hope my editor cleans it up before publication), I'll tell you all about it.

F&SF often features brilliant stories. Last month, the magazine had an unheard-of quality of 4.5 stars, just under the theoretical maximum of five. This month, we're at the nadir end of quality. It's readable but fluffy, forgettable stuff.

Story #1, The Martian Store by Howard Fast, recounts the opening of three international stores, ostensibly offering a limited set of Martian goods. They are only open for a week, but during that time, they attract thousands of would-be customers as well as the attention of terrestrial authorities. After the Martian language is cracked, it is determined that the Martians intend to conquer the Earth. The result is world unity and a sharp advance in technological development. Shortly thereafter, an American company begins production and sale of one of the Martian products, having successfully reverse engineered the design.

Except, of course, in a move that was well-telegraphed, it turns out the whole thing was a super-secret hoax by that company in order to create a demand for those putatively Martian products. World peace was a by-product. Thoroughly 3-star material.

G.C. Edmondson's From Caribou to Carry Nation is a gaudily overwritten short piece about transubstantiation featuring an old man who is reborn as his favorite vegetable… and is promptly eaten by his grandson. Two stars, and good riddance.

Plenitude, by newcomer Will Worthington, is almost good. It has that surviving-after-the-apocalypse motif I enjoy. In this story, the End of the World is an apparent plague of pleasure-addiction, with most of the human population retreating into self-contained sacks with their brains hooked into direct-stimulation machines. It doesn't make a lot of sense, but the quality is such that I anticipate we'll see ultimately see some good stuff from Worthington. The editor says there are three more of his stories in the bag, so stay tuned.

There is a rather pointless Jules Verne translation, Frritt-Flacc, in which a miserly, mercenary old doctor is given a lordly sum to treat a patient only to discover that the dying man he came to see is himself. Two stars.

Then there is I know a Good Hand Trick, by Wade Miller, about the magical seduction of an amorous housewife. It's the kind of thing that might make it into Hugh Heffner's magazine. Not bad. Not stellar. Three stars.

I'll skip over the second half of Starship Soldier, which I discussed last time. That takes us to Damon Knight's column, in which he laments the death of the technical science fiction story. I think Starship Soldier makes an argument to the contrary.

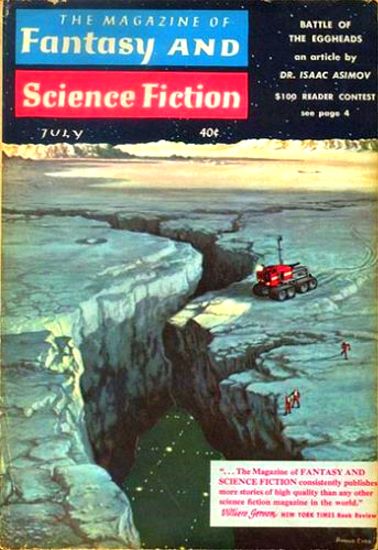

Then we've got Asimov's quite good non-fiction article, C for Celerity, explaining the famous equation, E=MC^2. I particularly enjoyed the etymology lesson given by the good doctor regarding all of the various scientific terms in common physical parlance. I've been around for four decades, and my first college major was astrophysics, yet I never knew that the abbreviation for the speed of light is derived from the Latin word for speed (viz. accelerate).

James Blish has a rather good short-short, The Masks, about the futuristic use for easily applied nail polish sheets. It's a dark story, but worthy. Four stars.

Ending the book is John Collier's After the Ball, in which a particularly low-level demon spends the tale attempting to corrupt a seemingly incorruptible fellow in order to steal his body for use as a football. Another over-embroidered tale that lands in the 2-3 star range.

That puts us at three stars for this issue, which is pretty awful for F&SF. Given that Astounding looks like it might hit an all-time low of two stars, here's hoping this month's IF is worthwhile reading. Thankfully, I've also picked up the novelization of Walter Miller's A Canticle for Leibowitz, and it's excellent so far.

Back in a few days with a convention report and a book review!

—

P.S. Galactic Journey is now a proud member of a constellation of interesting columns. While you're waiting for me to publish my next article, why not give one of them a read!

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has  comments. Please comment here or there.

comments. Please comment here or there.

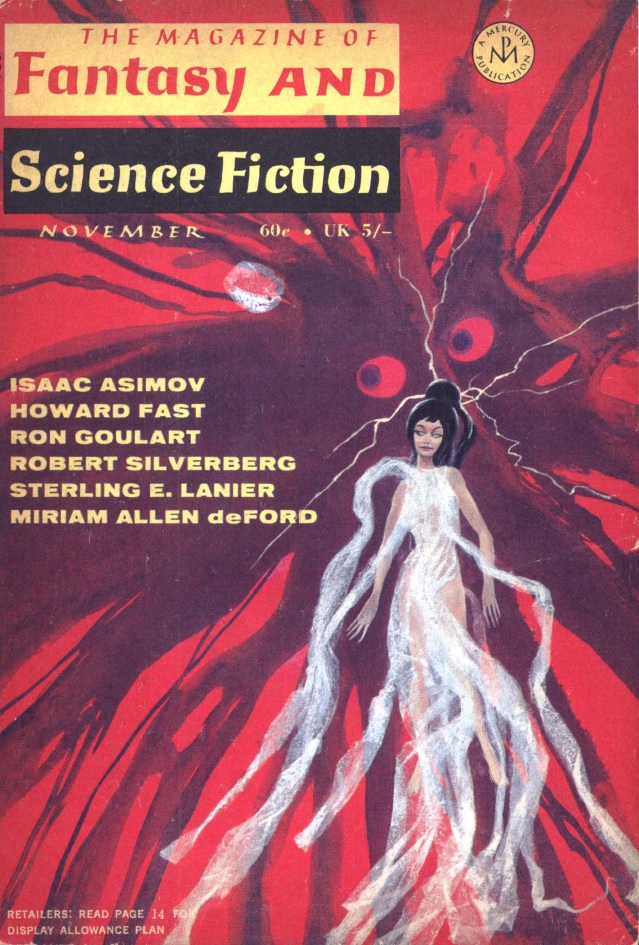

![[October 24, 1969] How sweet it isn't (November 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/691024fsfcover-639x372.jpg)