[if you’re new to the Journey, read this to see what we’re all about!]

by Gideon Marcus

"…but she took off the great lid of the box with her hands and scattered all these and her thought caused sorrow and mischief to men."

So goes Hesiod's account of Pandora, the first woman, and how woe was delivered unto mankind. Until last month, I'd come to believe that the box was strictly allegorical. And then I found it.

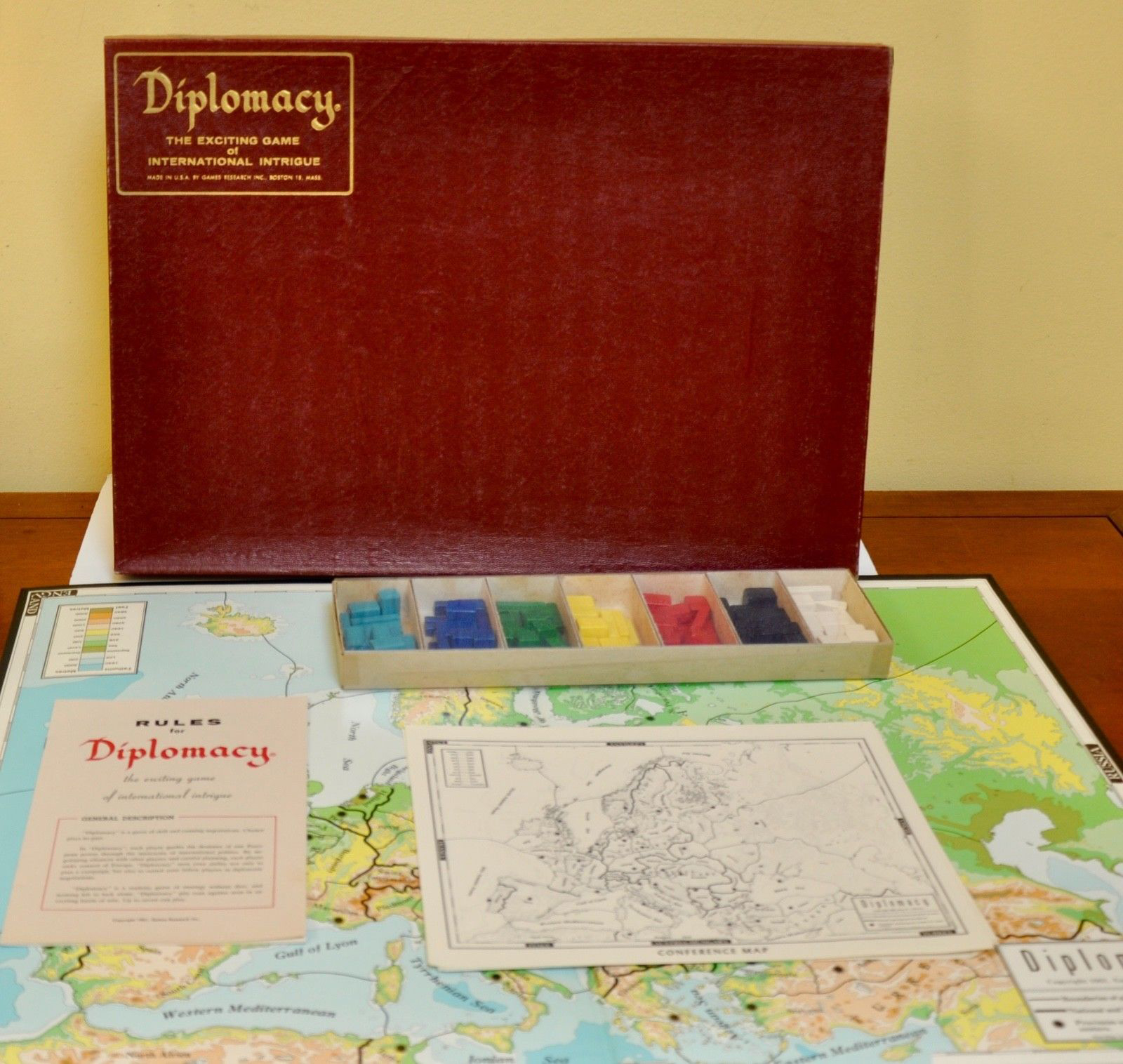

More accurately, I bought it. I was visiting the local toy store. You know, where they sell big bouncy balls, Airfix model kits, Erector Sets. And social, wholesome boardgames like Clue and Scrabble. Mixed among these innocuous pleasures was something new, a creation of the "Games Research" company. Its title was brief and opaque: Diplomacy. Intrigued, I purchased it and took it home.

Inside the maroon box is a map of Europe delineated with the pre-WWI national boundaries, a variety of wooden pieces, and a set of rules. "'Diplomacy' is a game of skill and cunning negotiations," they proclaim. Diplomacy appears to be the latest in the new category of diversions known as "wargames." The goal is to take the role of one of the seven Great Powers and take over the rest of Europe.

What makes Diplomacy unique from other wargames is its multi-player aspect; all the other wargames I've played to date have been two-player affairs. Also, as the rules go on to say, "Chance plays no part." This is true – no dice are included with or employed by the game.

Though the rules booklet runs several pages, the gist of the game is incredibly simple. The map is divided into two types of provinces: ones with "supply centers" and ones without. All player nations start out with three supply centers (except Russia, which gets four). No nation may have more pieces than supply centers; thus, each player starts with three (or four) pieces. These pieces may be armies, which move on land, and fleets, which may move in sea spaces or land spaces that border sea spaces.

Each turn, a player dispatches orders to each of her/his pieces privately in writing. Units are directed to move, either individually or with the support of adjacent friendly pieces. Orders are resolved simultaneously – in the event that two units are sent to the same province, the one with more support wins, and the other must retreat. Every other turn, control of supply centers is tallied – they belong to whomever was last in them on a tallying turn. And so the fortune of nations rises and falls. When one has control of no supply centers, that player is eliminated from the game.

Easy, no? Ah, but here's the tricky bit. Turns are divided into two segments. The latter is the one just described, where players write their marching orders. The former is a 15-minute diplomacy segment. This is the period in which players discuss their plans, try to hatch alliances, attempt to deceive about intentions. It is virtually impossible to win the game without help on the way up; it is completely impossible to win without eventually turning on your allies. Backstabbery is common, even necessary. Honesty is a vice.

Diplomacy is, thus, not a nice game. In fact, I suspect this game will strike rifts between even the best chums. So why play at all? Why suffer 4-12 hours of agony, especially when you might well be eliminated within the first few turns, left to watch the rest of your companions pick over your bones?

Well, it's kind of fun.

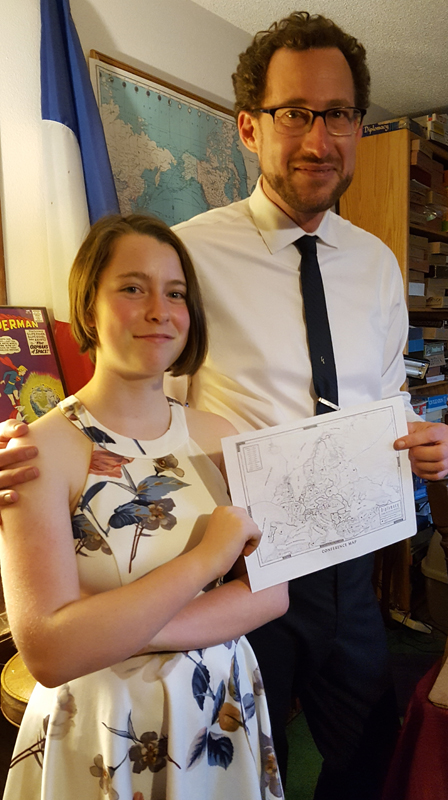

I'll give you an example. Last weekend, I was fortunate to have over exactly the seven people needed to play. We drew our countries randomly – I picked Russia, my daughter got the neighboring country of Turkey. Right away, we had to establish our relationship. Would we forge a treaty, enabling us to strike west into central Europe? Or would we be adversaries, soliciting the aid of another power (say, Austria-Hungary) in a bloody war for domination of the Black Sea?

As it turned out, the question was not neatly answered. As my forces fenced with the British Royal Navy for control of Scandinavia, and Italy plunged into the south of France, the Hapsburg Emperor proved a stubborn foe. After several turns of thwarting Turkey's Balkan ambitions, she convinced Lorelei to launch a surprise attack against my rear, the Sultan's forces heading straight for Sevastopol.

Only two things kept the Czar on the throne: Firstly, I'd penned a secret alliance with the Kaiser to join in a three-way alliance to devour the Dual Monarchy. Secondly, and more luckily, Lorelei had botched her orders, and her attack stalled.

I held absolutely no grudge against the kid. Instead, I merely pulled her aside during the next diplomacy session and explained that she could work with me and finally break out of Asia Minor…or she could not cooperate, and both our chances of winning would be slim. She bit, and next turn, Austria-Hungary ceased to be. We went on to tie for first place, both of us having a full eight supply centers when we called it a day after five hours of play. But I've no doubt that, had we decided to continue, my dear daughter, apple of my eye, would not have hesitated to drive the knife deep into my spine.

Such is the nature of Diplomacy. It's an unique pleasure, to be sure, one that will test your cunning, your generalship, and your charisma. And your friendships. Don't say I didn't warn you…