by Gideon Marcus

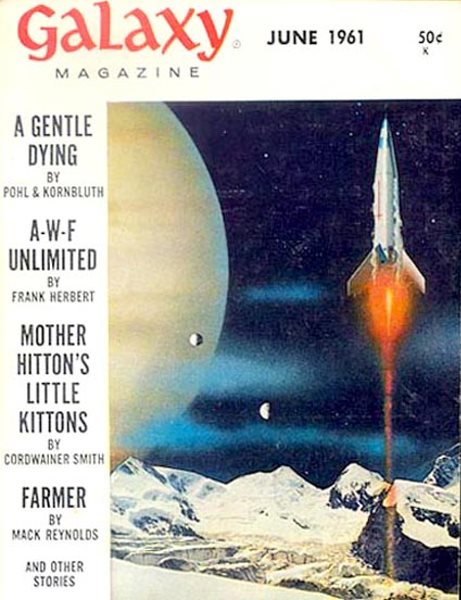

It doesn't take much to make me happy: a balmy sunset on the beach, a walk along Highway 101 with my family, Kathy Young on the radio, the latest issue of Galaxy. Why Galaxy? Because it was my first science fiction digest; because it is the most consistent in quality; because it's 50% bigger than other leading brands!

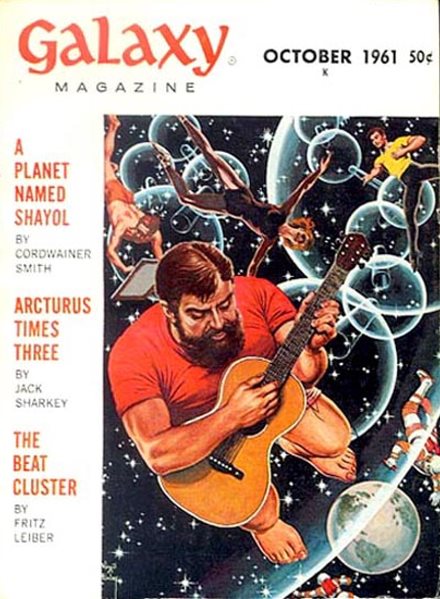

And the latest issue (October 1961) has been an absolute delight with a couple of the best stories I've seen in a long while. Come take a look with me – I promise it'll be worth your while.

First up is A Planet Named Shayol, by Cordwainer Smith. Smith's is a rare talent. There are few writers who not only excel at their craft, but they somehow transcend it, creating something otherworldly in its beauty. Ted Sturgeon can do it. I'm having trouble thinking of others in this class. Almost every Smith story has this slightly lilting, 10% off-plane sense to it.

Shayol is set in the far future universe of the "Instrumentality," a weird interstellar human domain with people on top, beast creatures as servants, and robots at the bottom of the social totem pole. This particular novelette introduces us to the most peculiar and forbidding of Devil's Islands, the planet Shayol. Just maintaining one's humanity in such a place of horrors is a triumph. The story promises to be a hard read, yet Smith manages to skirt the line of discomfort to create a tale of hope with an upbeat ending. Plus, Smith doesn't shy from noble woman characters. Five stars.

Robert Bloch comes and goes with little stories that are either cute, horrific, or both. Crime Machine, about a 21st Century boy who takes a trip back to the exciting days of gangster Chicago, is one of the former variety. Three stars.

Another short one is Amateur in Chancery by George O. Smith. A sentimental vignette about a scientist's frantic efforts to retrieve an explorer trapped on Venus by a freak teleportation mishap. Slight but sweet. Three stars.

I'm not quite sure I understood The Abominable Earthman, by Galaxy's editor, Fred Pohl. In it, Earth is conquered by seemingly invincible aliens, but one incorrigible human is the key to their defeat. The setup is good, but the end seemed a bit rushed. Maybe you'll like it better than me. Three stars.

Willy Ley's science article is about the reclaimed lowlands of Holland. It's a fascinating topic, almost science fiction, but somehow Ley's treatment is unusually dull. I feel as if he's phoning in his articles these days. Two stars.

Art by Dick Francis

Mating Call, by Frank Herbert, is another swing and miss. An interesting premise, involving a race that reproduces parthenogenetically via musical stimulation, is ruined by a silly ending. Two stars.

Jack Sharkey usually fails to impress, but his psychic first contact story, Arcturus times Three, is a decent read. You'll definitely thrill as the Contact Agent possesses the bodies of several alien animals in a kind of psionic planetary survey. What keeps Arcturus out of exceptional territory is the somehow unimaginative way the exotic environs and species are portrayed. Three stars.

If you are a devotee of the coffee house scene, or if you just dig Maynard G. Krebs on Dobie Gillis, then you're well acquainted with the Beat scene. Those crazy kooks with their instruments and their poetry, living a life decidedly rounder than square. It's definitely a groove I fall in, and I look forward to throwing away my suit and tie when I can afford to live the artistic life. Fritz Leiber's new story, The Beat Cluster is about a little slice of Beatnik heaven in orbit, a bunch of self-sufficient bubbles with a gaggle of space-bound misfits — if you can get past the smell, it sure sounds inviting. I love the premise; the story doesn't do much, though. Three stars.

Last up is Donald Westlake, a fellow I normally associate with action thrillers. His The Spy in the Elevator is kind of a minor masterpiece. Not so much in concept (set in an overcrowded Earth where everyone lives in self-contained city buildings) but in execution. It takes skill to weave exposition with brevity yet comprehensiveness into a story's hook – and it does hook. Westlake also keeps a consistent, believable viewpoint throughout the story, completely in keeping with the setting. I find myself giving it five stars, for execution, if nothing else.

Add it all up and what do you get? 3.3 stars out of 5, and at least one story that could end up a contender for the 1961 Hugos (I really enjoyed the Westlake, but I feel it may not be avante garde enough for the gold rocket). Now that's something to smile about!