by Victoria Lucas

Have you been following the talk about Orson Welles’s latest movie, one he personally wrote and edited? While not precisely science fiction, it does overlap thematically, enough so that I'm certain you'll enjoy a summary.

I was fortunate enough to catch the interview with him by Huw Wheldon on the BBC, or “The Beeb” as people across the Pond say. First off, Welles talks about changes he made from the novel by Franz Kafka. He says the main character (Josef K.) “doesn’t really deteriorate, certainly doesn’t surrender at the end” like the character in the novel. That’s true, more or less, but listen carefully to Anthony Perkins playing K. at the very end and ask yourself why he doesn’t throw what he is reaching for.

I know, I know, what am I doing writing a review for a movie that hasn’t been released in the States yet. Well, it was released in Paris, and quite a lot of people had something to do with the production and showing. I hate to tell you this, but a copy somehow found its way into the hands of a friend of mine. I can’t tell you any names, and I know no more than the name of my friend. The copy is a bit, all right, under par, not like seeing it in a movie house, but it’s exciting to see the film many months before I possibly could have otherwise. The earliest premiere in the US is in NYC, and I stand a snowball’s chance in hell of making that or any showing not in Tucson or Phoenix. I would prefer to watch a non-bootleg copy and probably will sooner or later, but beggars can’t be choosers.

When the beginning title hits the screen, the recently discovered (1958) and orchestrated “Adagio in G Minor” by Tomas Albinoni begins a beat of what I can’t help but think of as a dirge before we see the opening parable, done in something called “pinscreen” graphics. The title, by the way, is most remarkable for the fact that there is no trial in “The Trial.”

Of course we must keep in mind that a German word for "trial," the title of the film and the Franz Kafka book that “inspired” it (according to Welles), is Der Prozess. Also spelled "Process," this word in German means "process, trial, litigation, lawsuit, court case." There are other words for "judgment, tribunal, trial": "das Gericht," which at least has the word "right" in it; and "die Verhandlung," meaning "negotiation, hearing, trial."

It turns out there are numerous words that might apply to what we in the US would call a "trial" by judge and/or jury or any litigation: there are also "die Gerichtsverhandlung," "die Instanz" (which also means "authority, court." Why did Kafka choose "der Prozess," and why are some of the words feminine rather than masculine (like Prozess) or even neutral? These are fine points of German as a language that I cannot reach from my one college semester of German. It just appears to me that German has as many words for legal proceedings as the Eskimos are said to have for snow. However, in this case the word "process" in English is fitting, because we never see a trial, only one hearing, during which the protagonist, Josef K. (with only an initial and not a full name, as if the author was protecting a real person) speaks and brands himself as a troublemaker. (All legal proceedings in this alternate system of law are supposed to be secret.)

What we see in this film is a process indeed, a destructive process during which an innocent is exposed to corruption and chaos he never dreamed existed. The book makes it much clearer that the system that crushes Josef K. is not related to the uniformed police and visible court system. In fact, near the end, as K. is being frog-marched to a place of execution, he aids his captors in avoiding a policeman to whom he might have complained to prevent what was, after all, an abduction. This network is underground, with courtrooms and file rooms in attics throughout the unnamed city. Those enmeshed in it are “The Accused” as well as (illegal) Advocates and various officers and employees of the “court,” not to mention families who move their furniture and abandon their flats so that hearings can occur. One character remarks (in both the book and film), “There are court offices in almost every attic” and “Everything belongs to the court.”

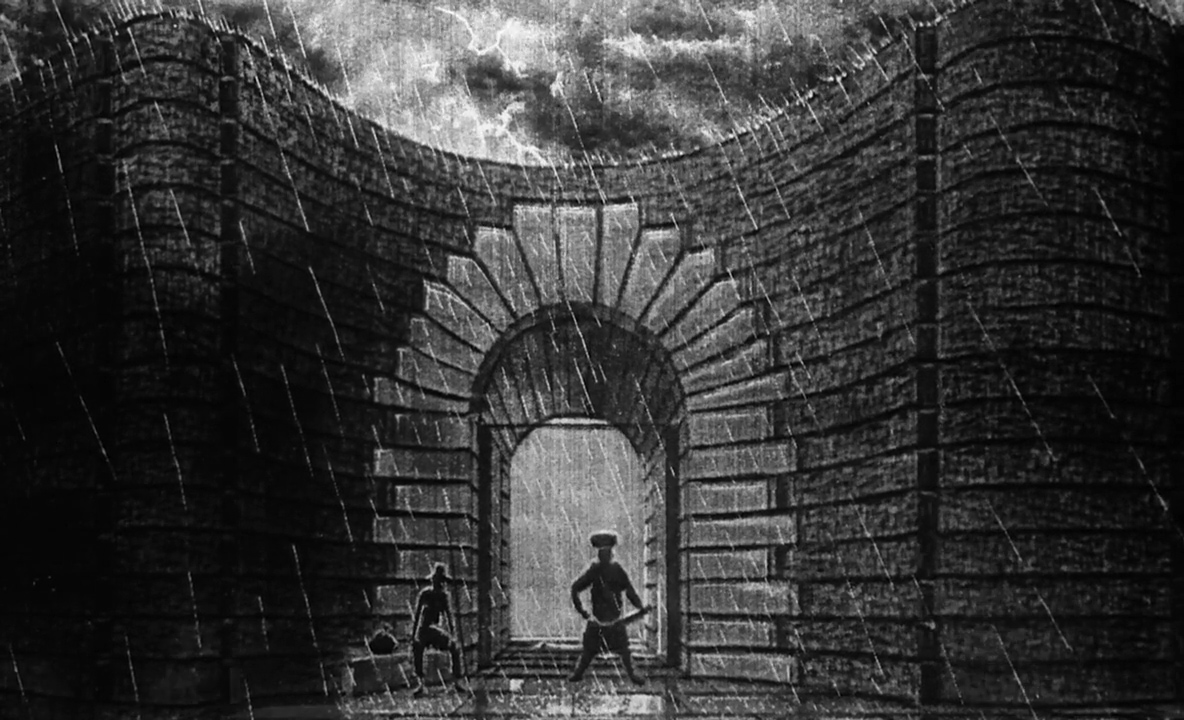

Welles changes this secrecy and underground nature to connect “the law” to the visible law courts by having K. exit a massive public building (actually in Rome or Zagreb), having entered it through a tenement at the back, in line with his view that “this is now 1962, and we’ve made the film in 1962.” During this century the classism and racism that were beneath public consciousness but engraved in the law, as well as officially tolerated or encouraged vigilantism, came into the open in a big way, like the difference between law practice in a makeshift courtroom and that in Grecian-style marble halls supported by uniformed officers of court and police.

The author of the original book, Das Process was killed by an early 20th-century epidemic we now call tuberculosis, dying at age 40 in Austria. (I am tempted to say, “died like a dog,” as K. characterizes his own murder or, in the logic of the book, execution.) Born Jewish in the kingdom of Bohemia, Kafka was a lawyer who worked for insurance companies. This book would have been destroyed had his executor followed his instructions, but instead the order of the written chapters (mostly finished, apparently—I saw only one chapter labeled “unfinished”) were determined by his editor/executor and the book was originally published in 1925, a year after Kafka’s death. Welles mentioned the Holocaust in the BBC interview as his reason for changing the ending, choosing “the only possible solution” (rather than the “Final” one) to negate the choices made “by a Jewish intellectual before the advent of Hitler.” So I feel justified in seeing much that relates to racism, not to mention sexism and classism. Kafka was reportedly a socialist with some tendencies toward anarchism.

According to Welles, the movie was filmed partly in Zabreb, Yugoslavia (exteriors), with most interiors in Paris (the Gare d’Orsay and a Paris studio), and some exteriors in Rome. Welles would have filmed in Czechoslovakia, but Kafka’s work is banned there. The last scene was shot in Yugoslavia, and so were the scenes with 1,500 desks, typewriters, and workers in a huge room for which they could locate no place but the Zabreb “industrial fair grounds” (scenes at K’s workplace, which do not correspond with the descriptions in the book).

The partly abandoned Gare d’Orsay, in contrast to the other locations, was a huge seminal find for Welles, one that appeared to him at the end of a long day in which he learned that sets in Zagreb could not be finished in time to make his schedule or possibly even the film, if he could not find another location quickly. Originally the Palais d’Orsay, subsequently a railroad station with platforms that became too short for long-distance use, the station was mostly abandoned, but the building included a 370-room hotel. Welles quickly changed his plans from sets that dissolved and disappeared to one that was “full of the hopelessness of the struggle against bureaucracy” because “waiting for a paper to be filled is like waiting for a train.”

The gossip is that producer Andrew Salkind agreed to underwrite Welles’s project only if he could find a book to base it on that was in the public domain. They both thought this work by Kafka was such a book, but discovered that they were wrong and had to pay for the use of the story, reducing the budget for the film. Several people are credited with the writing, with Welles himself reading the titles at the end, but he says he wrote as well as directed and acted in it. Rumor also says he wanted Jackie Gleason (yes, “Honeymooners”) to play the role he played, that of a lawyer Kafka named Dr. Huld (German for “grace” or “favor”) but that Welles christened “Hastler” (hassler? what the lawyer should do to the courts but not to the clients?).

There are some problems with Welles’s editing, the main one in my view concerning a scene with a wall of computers at the bank where K. is a middle-rank executive. As it is, the scene is quite pointless and appears to exist only to show how up-to-date the film is compared to the 1925 novel. However, it was originally a 10-minute scene in which Katina Paxinou (a face on the cutting-room floor) uses the computers to foretell K’s future (wrongly…OK, mostly wrongly). It was “cut on the eve of the Paris premiere,” according to my notes on the BBC interview—in other words done in haste and, as in the proverb, made waste, but Welles clearly felt there was something wrong with the scene and saved us from most of it.

Nevertheless, on the whole Welles felt good about “The Trial.” In the BBC interview he summed it thusly, “So say what you like, but ‘The Trial’ is the best film I have ever made.” I’m not sure I agree, but it’s definitely worth watching, even taking the time to compare it with the book. (But beware of any resulting depression.)

[P.S. If you registered for WorldCon this year, please consider nominating Galactic Journey for the "Best Fanzine" Hugo. Check your mail for instructions…]